Show a Little Leg | A Conversation with Greg Marshall

Interviews

By Lucas Schaefer

My husband likes to tell a story about our second date. We were at Magnolia Cafe on South Congress Avenue. I was nervous. After our first date, I’d waited the requisite couple days and left him a voicemail asking to go out again. Greg had taken his sweet time responding. Then he showed up to dinner in ratty UT basketball shorts, the uniform of a man who knew he had the upper hand. Greg is from Utah, all blonde and blue, with the eyes of a Disney prince and teeth so big and white we have a running joke that he should go as Jane Pauley for Halloween. The gee-whiz looks belie a randy sense of humor and a general air of flirty mischief; his vibe is Dennis the Menace, all grown up and ready to bone. From the moment I met him, I was a little bit in love.

This second date went well—so well that, before we paid the check, Greg worked up the nerve to mention his limp. “Your limp?” I asked. “You limp?” This was not a well-intentioned if misguided gesture, a twist on the “I don’t see race” claptrap familiar to many children of the 90s. To intentionally not see something, you have to see it in the first place. A limp? I thought. Is this guy nuts? After two dates, I was pretty sure I’d have noticed.

Greg, it turned out, did have a limp, and—as I’d come to learn—it was a source of aggravation, obsession, and sometimes shame for him. Years ago, when Greg first started telling the story of our second date, the moral was that I was so absent-minded I’d somehow missed his limp (he still sometimes calls me Nutty, as in the Professor). But it’s also true that, at the beginning of our relationship, Greg went to great lengths to minimize his unsteady gait: coming early to our dates so he’d be sitting when I arrived, always letting me lead the way from A to B.

Back then, in 2011, Greg still believed his limp was the result of “tight tendons,” the phrase his family had always used to explain it. Three years later, while applying for health insurance, Greg had to track down a copy of his childhood medical records. That was when he learned the truth. As a toddler, he’d been diagnosed with mild cerebral palsy, a fact his parents had kept from him.

If you’d told me twelve years ago that Greg would have a memoir coming out in 2023, I wouldn’t have been surprised. By the end of that second date, I already knew that Greg’s beloved dad had died a couple of years before from ALS and that his fiery, charismatic mom had been battling cancer for more than three decades. Throw in Greg’s four raucous siblings, and the book could practically write itself.

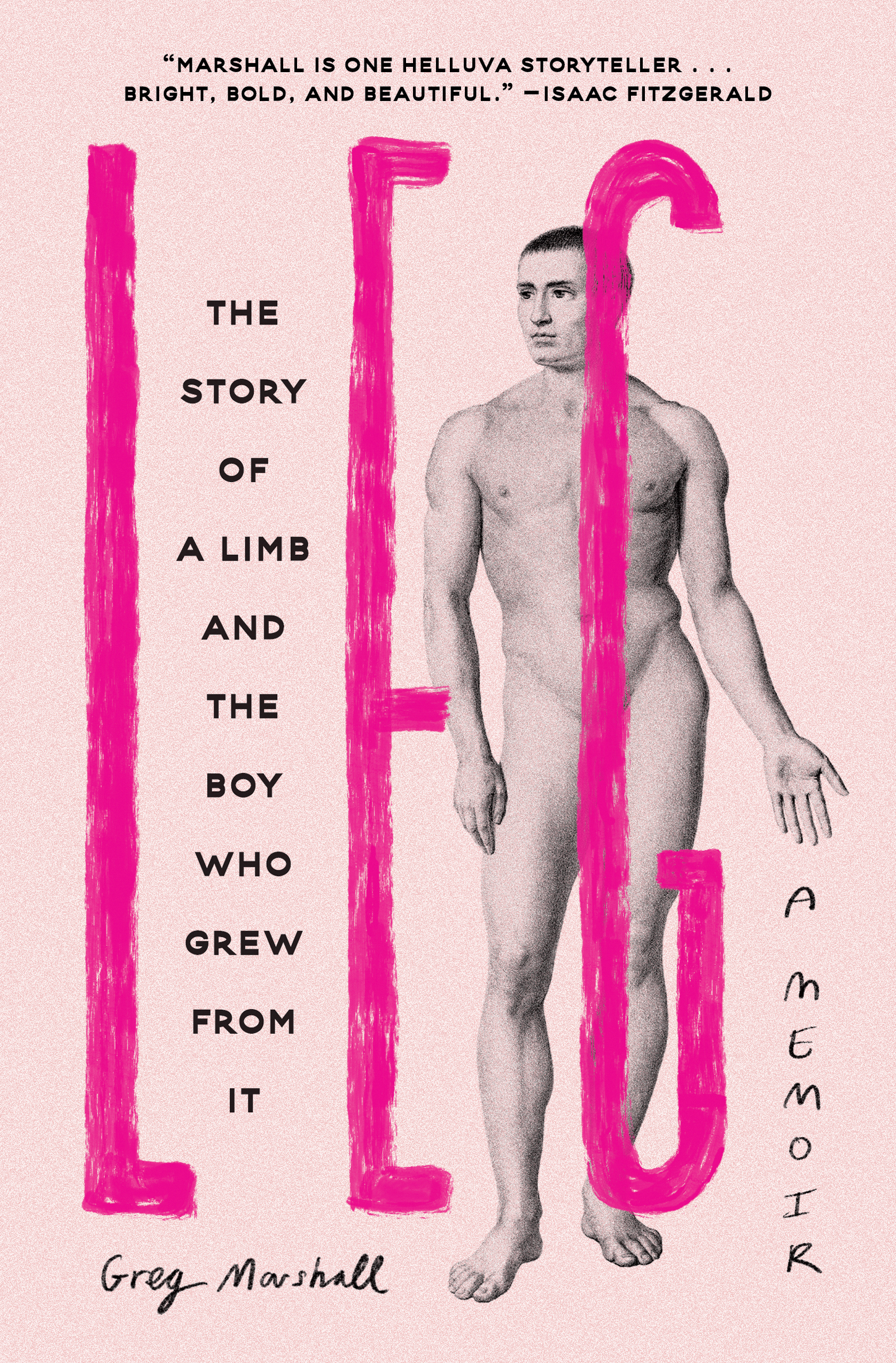

What I wouldn’t have predicted is that said memoir would largely center around Greg’s leg. Leg: The Story of a Limb and the Boy Who Grew from It (Abrams Press) is about growing up gay in Utah and the tumultuous years afterward, navigating classrooms, newsrooms, and bedrooms with a disability he never exactly knew he had. For much of his life, my brilliant writer husband didn’t have the language to describe his experience. Now he does, and lucky for us, he uses it.

One of our frequent date spots is Barton Springs, the massive, spring-fed pool in Austin’s Zilker Park. It’s hard to feel self-conscious at the Springs (if you’ve seen some of the questionable swimsuits we’ve worn there over the years, you’ll know I speak the truth). Every size and shape is on display, and, with all due respect to Planet Fitness, it’s as close to a true “Judgment Free Zone” as I’ve ever been (the water’s too cold for censoriousness). It seemed an appropriate place for Greg and me to lay down a towel and talk about the strangeness of living in a body, those wily Marshalls, and his beautiful new book.

Lucas Schaefer: When you started writing your book, the idea was, Let me tell you about growing up gay in Utah with “tight tendons.” Then, after you’d begun writing, you learned you were diagnosed with cerebral palsy as a toddler but that your parents never told you about it. The day you called me downstairs and said, “You need to look at this medical chart,” you’d already been working on a memoir for a year. Can you talk about how the project evolved after learning you have CP?

Greg Marshall: I’ve always been interested in the body and how we navigate having bodies. But, before finding out about CP, my leg remained in the background. I never knew how to talk about it without feeling powerless and ill-informed—or like I was faking it, whining about nothing, or being ungrateful. The part of myself I did know how to talk about was coming-of-age as a gay man. I’ve always been relatively fearless—or at least unfiltered—when it comes to talking about sex and desire and masturbating with my mom’s back massager from Brookstone when I was a boy. So, before I found out about CP, I called my memoir project Long-Term Side Effects of Accutane and pitched it as a raunchier The Wonder Years. I led with my sexual identity because that was a category I fit into, one that I understood.

LS: When we first met, I don’t think you would’ve ever labeled yourself “disabled.”

GM: Right. In a fiction workshop in grad school the semester before we met, I wrote a nonfiction piece that I presented as fiction. It was about going to Disney World with my mom and little sister. I had a limp in the story, but I never really went there. And the other people in the workshop were like, How is this character navigating Disney World with a disability? Is he in discomfort? Can he go on all the rides? Like, what’s going on here? Looking back, I was dissociating. But I was also exploring, groping in the dark for a sense of who I was. Learning about CP gave me a body. In my stories, it gave me a physical presence that I recognized as myself. And once I invited my body to the party, the rest of me started showing up on the page as well.

LS: I think the conventional wisdom is that you need distance from a subject to write effectively about it in memoir. But you were going through the process of learning about CP and conceiving of yourself as disabled as you were writing the book.

GM: At first, I was furious with my parents for not telling me that I had CP. Part of the reason I was so angry was because I was writing a book about my life. I felt like they’d really hung me out to dry.

LS: Like you’d been writing these stories that were, in a way, untrue?

GM: It was just an extreme example of what it’s like to not have basic information about your body and your experience. Here I was being a bard, telling these stories, and I didn’t have the most basic facts about myself. I was telling a version of my life where my disability had been erased from the record.

LS: So how did you not let the rawness of the emotion overtake the narrative? Because, as it was happening, you were pretty pissed.

GM: It took a lot of drafts and a lot of rejections from literary magazines and agents and editors to tell a story that had some bite to it but wasn’t angry and bitter. The revision process naturally lent me a cooling-off period that gave me the chance to layer in thought and compassion, have conversations, and put my parents’ deceit in perspective.

LS: If you had a less mild version of CP, your parents couldn’t have hidden it from you. That’s one of the things that makes your story unusual.

GM: Yeah. I mean, I wasn’t grievously wronged. It’s not as if CP is a progressive disorder. I wasn’t denied treatment that I would’ve gotten otherwise. But when you’re denied the facts, you kind of become the punchline and go through things alone. I don’t have a good sense of direction and, for years, I made fun of myself and said it was because I’m ditzy. And now it’s like, no, I have CP, and I need to give myself a little longer to figure out where I’m going. I’m not an idiot; my spatial reasoning is impaired because of brain damage. So yeah, my experience is unique. My leg, my disability, is very much my own. Ultimately, I realized there was no one who would tell my story but me, and no one could tell it better than I could.

The upside of all this in-the-moment processing is that it let me incorporate disability into the narrative of my life relatively quickly. Suddenly, I was the one in control again. I felt like an investigative journalist, and CP was my big break. I had the missing piece that made everything else make sense. In a way, receiving my diagnosis gave me the distance I needed to write about my experience because it made my “tight tendons” feel less amorphous and random.

LS: It’s worth pointing out that, as all of this was going on, at no point were we not intimately involved with your family: Christmas, family reunions, we did it all. What’s it been like writing about your family all of these years while, you know, still being in it?

GM: I would say it’s occasionally stirred up some shit. Generally speaking, there’s a reason things often go unsaid in families, even ones that are quite close like mine. But overall, writing the memoir has made me so much more invested in being a member of my family because it’s helped us understand each other and have conversations we might not have had otherwise. The alternative to writing about your family is that those memories just disappear. I thought about that a lot after my dad died in my early twenties. Writing is a way to keep people alive.

LS: Did learning you have CP make you see your family differently?

GM: CP helped me see that disability was a source of intimacy and connection in my family. It let me see my family from a disabled perspective rather than an able-bodied perspective. The two most obvious examples of this come from my parents, especially my dad and his ALS. Our disabilities—the things we could and couldn’t do—became something we had in common.

It didn’t stop with my parents, either. The more I looked around at my life, the more I saw that disability is part of being human: the bestie with a pacemaker, the high school crush with a stutter. Lucas, early in our relationship, I remember your mom telling us that you briefly slept with a bar between your legs as a toddler because you were pigeon-toed. I thought it was endearing. Wow, this guy walks on his toes, too! What if, instead of something to be feared, all the things that were “wrong” with us were the very things that brought us together?

LS: That’s a diplomatic answer. Tell us more about the shit-stirring.

GM: That’s why people should read the book: all the dirt! I will say one thing I learned from writing nonfiction is that the term essay is really apt. Because, just like in a college essay, you’re arguing a point through storytelling. You have to have a thesis, and it’s OK if that thesis is not something that’s universally agreed upon. In fact, your thesis needs to reflect you. That’s the whole point. What I wanted to do in the book was tell the non-Christmas card version of events, the version of events that wasn’t handed down to me. Doing that can be taboo, especially when disability is in the mix, but it’s also very liberating.

LS: In addition to being a family story, and a disability story, Leg is very much a Utah story. When we watch movies or TV shows set there, you often say you feel like the place isn’t quite being captured. What do you think is missed, and how did you try to remedy that in Leg?

GM: In TV shows, there’s usually an emphasis on fairly conservative, if not fundamentalist, Mormonism. Not as much attention is paid to outsiders. When you’re portraying Mormons to the outside world, they’re the curiosity. But, in Utah, we’re the curiosity. And “we” includes anybody who falls off the wagon: non-Mormons; gay people; neurodiverse people; people who don’t get married in their early twenties. Ultimately, that’s a lot of people, and many of them are Mormons themselves.

LS: There’s certainly an “us and them” quality to Utah. The drinkers vs. the non-drinkers, for example.

GM: In Utah, many things are reactions to Mormonism: drinking or not drinking, swearing or not swearing, being a believer or an apostate. You either go to church on Sunday or ski on Sunday. One upshot of living in a culture that makes a fetish of perfection and shuns people who don’t fit the religious—or sexual, or able-bodied—mold is that it leads to self-delusion and addiction. A lot of people are left out, and being left out hurts. How do you pick a side if you have no side? In Leg, I wanted to show what it’s like for people in between—the ones who don’t go to church, who don’t ski every day off—and the best way I knew to do that was through the story of me and my family.

LS: As someone who has observed the state for many years as your husband, I can also say adult Utahns love Disney in a way that I find . . . a little weird?

GM: The love of Disney really transcends. That’s the other thing about Utah that isn’t portrayed: it’s a very queer culture. It’s just that the gay part isn’t usually acknowledged.

LS: You mean because Utahns like campy entertainment?

GM: Yeah, but they’re not in on the camp. Take something like Disney on Ice, which is very popular in Utah because it’s safe, family-friendly content. Gays are coming at that stuff with an ironic sensibility. But it’s not ironic to “straight” Utahns, especially ones of a certain age. Disney is a closet, a way of speaking in code, of expressing your repressed feelings in a big way. At least, that’s what Disney was for me as a closeted kid in my teens. I collected Disneyana because—

LS: You may need to define that term for the uninitiated.

GM: Disneyana?

LS: Yes, Disneyana.

GM: Disney collectibles—porcelain dolls and commemorative coins. Anything you can buy at a Disney Store, if they still have those . . .

LS: I was a Nickelodeon gay.

GM: Ours is a mixed marriage, Disney and Nickelodeon. But anyway, I think that’s why conservatives have found openly gay characters in Disney movies upsetting: they’re saying the quiet part out loud: All this is very, very gay.

LS: You have done a lot of coming out in this life: as gay, as disabled. Do you see yourself ever retiring from coming out, or is it a never-ending process?

GM: It’s not as much about coming out as it is who you let into your life, who you let into your most intimate and vulnerable moments. In some ways, we come out as a public service, in the way Harvey Milk encouraged. We come out because if we don’t, we’re letting dickheads define us, to butcher a turn of phrase from David Mitchell. I’ll always be out. There’s no question about that. But the question of letting in is a more urgent and evolving one. My need for privacy and self-preservation may change as I get older, as we have kids, or as people read the book. For now, at least, it feels like an enormous privilege and thrill to get to put a big, messy, intimate book out there in the world and just kind of see what happens.

LS: Has publishing a memoir been similar to coming out?

GM: Publishing a memoir has mimicked coming out in ways I didn’t expect: the jubilation, the relief, the overwhelming show of support, the fear of rejection from some of the people you love most. Publishing is public. As a memoirist, you’re really sticking your neck out there, and not everyone is going to be happy about it. Not everyone is ready to have a mirror held up to them, even if the reflection they see is widely understood to say more about the author than his subject. What I learned from coming out that has helped me in publishing is that you have to get used to taking up space. No one is going to carve out the space for you. People who say, “I’ll write about it when this or that person is dead” may be disappointed to find that the forest never really clears. For every hundred people who cheer you on, there’s always one person who would rather your story didn’t exist. If you let them, they will happily stand in your way.

LS: Your brother is a memoirist and screenwriter, and your mom worked as a journalist for many years. I’m a fiction writer. All of us have our own memories of things that happen in the book. What has it been like to be surrounded by writers as you write about them?

GM: Well, it’s dicey at times. To take a line from Nora Ephron, I’m from a family of cannibals, including you, babe. If somebody says something great at dinner, somebody else is going to use it. I think it makes you less precious about portraying people and putting your memories on paper. You understand that if you don’t do it, someone else in your life will. If I weren’t writing about discovering my disability at thirty, my brother would write about it, or my mom would write about it. It would be in all of her Christmas cards, and she would start a blog about it, and the next time I accompanied her to chemo, I’d be hearing about it from all her nurses. So, the question becomes, “Do you want to use the material and take the glory and take the hit? Or do you want to get scooped?”

That’s my snarky answer. Can I give you my schmaltzy answer?

LS: Let the record show Greg is about to log his “schmaltzy” answer about living among writers.

GM: I’d like to think that we’ve all been champions of each other’s work over the years: you, me, my brother. We’re always reading each other’s stuff and giving each other notes and encouragement. My mom was my first champion. Even before I did, she saw that writing and storytelling were things I could do at my own pace and in my own way. She and my dad were in the newspaper business—that’s how they met—and my mom let me “write” her newspaper columns with her and contribute my godawful junior high and high school poetry to the cause. Both of my parents made being a reporter seem like the slickest job on earth. They never told me that I was a terrible speller or that I misused big words. If I got an F on a writing assignment with a note that said, “See me after class,” as happened not once but multiple times in my adolescence, my mom would laugh and tell me my teachers were jealous of my talent. I’d redo the assignments in secret so I could get credit.

LS: Why were you bombing so many writing assignments?

GM: Ableism! No, I mean, I had mostly wonderful and empathic teachers. But I couldn’t spell, and I have serial killer handwriting, and, especially in my younger years, I’d let it rip creatively in ways that sometimes read as, “Does not follow basic instructions.”

LS: And your mom knew you were a star.

GM: My mom knew I was the biggest, gayest star in the state, yes.

LS: For reasons that remain unclear to me—and probably to most people who know you—you are currently on a committee to plan your twentieth high school reunion. If your high school classmates read the book, what do you think will most surprise them?

GM: You mean besides all the gay sex? They’d find me much more sharp-tongued and less agreeable on the page than when I was student body president. I remember posting an essay about CP on Facebook back in 2016. A very sweet acquaintance from high school left a comment, saying something like, “I had no idea you had CP. I maybe noticed you had a slight limp, but I just thought of you as the kid with the giant smile.” And honestly, that was enough to make me want never to post anything on Facebook again.

LS: It was almost a replay of what you’d experienced as a kid, where your difference wasn’t really taken seriously or legitimized.

GM: In that teenage sense, I felt like my experience as a human was being ignored. I just saw you as the kid with a giant smile. No, I want to be seen as a writer who might have things to say, not just a clown slipping in the mud.

LS: You date a couple of fabulists in the book. Without giving anything away, I think it’s safe to say the lies they tell you aren’t minor. They’re giant lies. And, of course, there’s the lie, or at least the omission, at the heart of this book about your disability. To what extent has having been on the receiving end of so many mistruths informed your work as a memoirist?

GM: I wanted to write nonfiction because the truth mattered to me. And I don’t mean just the objective, journalistic truth. I mean my truth and my version of the story. Because when you’ve been lied to, it’s like your own life story has been hijacked. At first, I felt a lot of self-recrimination about my leg. How could I be so stupid to fall for these lies? In some ways, Leg is about reclaiming the truth. I can flip through this book and say, This happened. This is the truth. I’m not gonna let anybody tell me what happened. This is what happened.

LS: You’re refreshingly frank in the book about how CP has impacted your sex life over the years, including with me. I’m curious about the experience of writing so intimately about us. We both work from home, so you could literally hear me, like, doing dishes as you’re describing trying to top me.

GM: I think that it’s more difficult to write about people in your life who are more at arm’s length. When you’re writing about your partner—we’re very intertwined, so it’s easy. I mean, you’re right there! But it’s different with the family members we don’t live around. There’s a slightly animatronic aspect to those relationships: we rear to life, or they rear to life for us, only when we’re visiting them over the holidays, and vice versa. When someone is at arm’s length, they’re just not as keenly aware of how much you love them. And that can be the more fraught space to navigate as a writer.

LS: We’ve spent many an evening watching RuPaul’s Drag Race. Given how much of Leg is about the joys and horrors of growing up, I think it’s appropriate to close with a bastardized version of a classic Ru question. With all the knowledge and perspective you have now, what advice would you give a five- or ten-year-old Greg Marshall (aside from, “Hey dude, you have CP!”)?

GM: Be glad you’re not circumcised. That foreskin is a gift.

LS: You just can’t stop yourself, can you?

GM: What I would tell myself is: “You’re going to meet a guy who will see and love all of you. And instead of running for the hills when you tell him about yourself, you two will work together for ten long years to have books that maybe neither of you would have had without each other. And, one morning many years from now, you’ll sit by Barton Springs, across from a guy in a thong with a tattoo on his ass, and you’ll talk about it all.”

Lucas Schaefer’s debut novel, The Slip, is forthcoming from Simon & Schuster. His fiction has appeared in Southwest Review (Volume 106.4), One Story, The Baffler, and elsewhere.

More Interviews