Every Word Carries Weight | An Interview with Jon Lindsey

Interviews

By Troy James Weaver

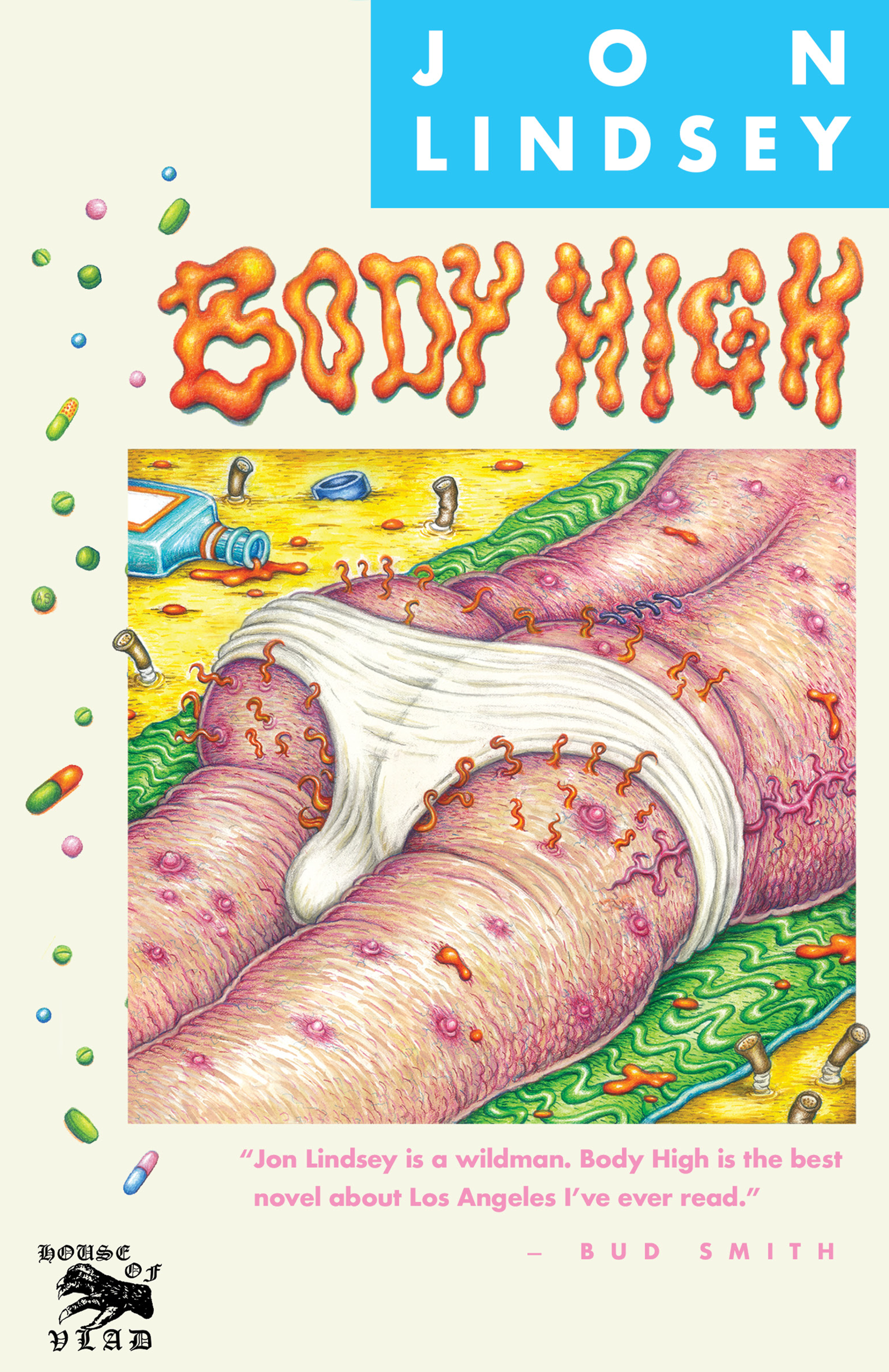

Jon Lindsey’s Body High is a highly impressive debut novel. It presents a vast panorama of an LA I’ve never quite seen. Nor have I read a book that reveals the inner workings of a soul in such a simultaneously searching, funny, and tragic manner. The novel begins with Leland, our protagonist, at his mom’s funeral. Everything that could go wrong at a funeral does, but to comic effect. Then we are taken on a strange odyssey through LA. See, Leland’s seventeen-year-old aunt, Jolene, needs a new kidney. And Leland plans on getting her one, because he doesn’t merely love Jolene but is in love with her.

Jon has been on my radar since I came across his writing online a couple of years ago. First I was blown away by his attention to language; then I was shredded by his audacity to be so authentic and real. His writing goes so deep, we can imagine every word chiseled into stone, and Body High is a testament to that.

Troy James Weaver: Body High is one of those rare books that has it all. Humor, action, sadness, incest, grief, and an actual plot. Yet under it all, there’s this emotional rawness that feels too real. Did you ever find yourself having trouble writing because it just got too heavy at times? If so, did you stop and recharge? Or did you just push through?

Jon Lindsey: I based a lot of the mom character in Body High on my own mom, so those sections were awful to write. Tao Lin told me they were his favorite parts of the book, and I think the reason for that has to do with that difficulty. Some days I would come home from visiting my mom in the psych ward or ER, and know that I needed to sit down and write. I’d feel like a failure because I hadn’t written for days, but I’d also be so drained physically and emotionally that writing was impossible. Other days, I’d be crying as I wrote about the mom character, and want to stop, but know I needed to keep going because the pain meant the writing was good. Those days, I’d take breaks and step away from the computer, kiss my wife, hug a dog, smoke a j, then get back to work.

TJW: I agree with Tao. There is something about those moments in the book; they feel energized in a different way from the rest of the book. I like the way you control those moments. People often say you should have distance from experiences and emotions before writing about them. Because you’ll have more to say about them, understand them better? I disagree. I believe there are certain things that you should write about almost as soon as they happen to you. I know I get hung up on the same things and write toward them all the time in various ways. What are your thoughts on this? I know that the book you are currently working on deals with the death of your mother as well, just differently. Would you tell me about that?

JL: I was writing Body High in the aftermath of my mom’s first attempt at suicide. So I was probably preparing myself for her death. After she died, I kept a journal. I had a voice in my head saying, “Peter Handke wrote Sorrow Beyond Dreams only seven-weeks after his mom’s suicide.” I felt like I needed to write a book within the same time constraint, while my feelings were fresh, before I started forgetting. The pressure was intense. Predictably, the seven-week deadline passed, and I felt like a total failure. Like I didn’t love my mom enough. The thing is, Handke’s book, while beautiful, is detached. He writes about his mother as a kind of everywoman. Probably, he was still in shock.

I want to write deeper and more personally about my own mom. Two years on, I no longer feel the same urgency, or pressure. Have you ever read another person’s journal? The entries tend to be written during periods of anguish. Initially I wanted to share my anguish with the world, but more and more I want to present a complete picture of my mom—moments of confusion, heartbreak, and love.

TJW: I totally get that. Telling the whole story. You can’t do that in the moment of the tragedy. You need distance to forgive, both yourself and whoever it is you are mourning. I felt that with my dad, still do. But I did feel it was important to write fresh when things happened. Now, I’m still writing about those things because I feel like I understand more and I’m learning to love him and myself better now that he’s gone. I think it’s good to go through the different phases of grief and acceptance, yet it feels like the work will never be done. Sometimes I feel like this kind of thing is prohibitive to my growth as a writer, always considering the same things from different perspectives or different modes. But also, I don’t think there are a lot of serious writers who move away from the things they feel they need to explore deeply. I’m obsessed with things I can’t explain. Do you think about these things? Are writers obsessed with things they don’t understand? Is that the point?

JL: As a writer, you must be obsessed with things you don’t understand. Especially, if that thing is yourself. I can’t imagine ever knowing myself, but nothing is more worthwhile than trying.

A lot of writers will disagree with me, and maybe they’re right, but I believe each of us only has two stories: our mother and father. We are the synthesis of those stories. In a sense, our life is a sort of re-telling, re-enacting, and recuperating.

TJW: Your sentences are sharp, tight, concise little jabs. Do you ever get tired of people saying that your writing is easy minimalism? I’ve seen it said about your work. Mind you, it wasn’t in a derogatory sense, but I know how I feel about those things, when they are said about me, so maybe I’m projecting. Do people not understand how hard-won those sentences can be?

JL: Most writers should use fewer words and say more. What is “easy minimalism?” Easy is dismissive. Easy is something people say when they don’t understand art, but want to feel superior. Like, “Eyy, my kid can paint that.” Good writing is never easy. Minimal writing requires that every word carry extra weight.

TJW: I couldn’t agree with you more. Good writing is never “easy,” especially minimalist writing. Every word carries weight, like you said. Who are some of your favorite writers in this regard?

JL: I admire how Sam Pink strips his stories to their essence. His style feels almost architectural, the way he doesn’t waste a word, and leaves space for the reader to sit with what is unsaid. Sam edited Body High, and I learned something from every word he cut. Kathryn Scanlan and Ashton Politanoff are cool Los Angeles minimalists in the tradition of Lish. I don’t know if Kimberly King Parsons and Nicolette Polek consider themselves minimalists, but all their words carry weight. During lockdown I started a workshop with Harris Lahti, Sean Thor Conroe, and Nathan Dragon; those guys know how to strip and rip a story. I’m always excited to see how Cory Bennett, Kelby Losack, Big Bruiser Dope Boy, and you, Troy, are working with language in a minimalist style. In the age of the internet not working with minimalism seems naive, or arrogant, which sort of makes me want to try.

TJW: I know you are a Houellebecq fan. What’s you favorite book by him and why?

JL: Twenty years later and we still haven’t caught up to Houellebecq’s Elementary Particles.

TJW: Mine is probably The Map and the Territory, mostly because he does that neat trick of killing himself off as a character in the book, but also its obsessiveness with art. And its insistence that art exists because people need something more than reality, which is sad. Art is telling us that we are lacking; that nature is lacking. Are there any maximalist writers you enjoy?

JL: I guess you could make the argument that’s a maximalist book, at least conceptually. But maximalist language? I don’t think it works today, unless it comes at us in a fire hose like ilongfornetworkspirituality.net or some of the writing on Expat Press.

Lately I’m re-reading a lot of the Romantics, writers like Novalis, Chateaubriand, and Kleist. That’s some maximalism. As a reader you try to unravel these wild sentences, in the same way the protagonist is trying to make sense of the world and their chaotic heart. I have a hunch that we are entering a new period of Romanticism. A returning to spirituality in order to escape—a childlike yearning for a heavenly father—the fantasy of being at the center of the universe. This summer I feel it in the air.

TJW: Did you ever take a writing class or are you completely self-taught? When did you decide to be a writer? To publish?

JL: In elementary school, I wrote raunchy plays for my classmates to perform. After dropping out of high school, I wrote poems and huffed silver spray paint. I got a GED, wrote for my community college newspaper, and enrolled in state college where John Fante’s biographer told me not to be such a wastoid. I did an MFA in Critical Studies at CalArts with conceptual artists and art critics. “Actually,” one of my teachers said, “I don’t think it’s possible to teach writing.” Eight years later, I published my first story, “The Ass is a Hole Where the Light Gets In.”

TJW: “The Ass is a Hole Where the Light Gets In” was the first story of yours I read. I immediately thought: “This. This is new and exciting.” I too am a high school dropout who got a GED. Sometimes I think my feeling like a fuck-up led me to writing. I just started taking art more seriously, because I realized I could never be an accountant or whatever. Did you have a similar experience?

JL: Yeah, I’ve only ever been good at writing, and even that’s debatable. But I always considered myself as a writer, even when I wasn’t writing. I took jobs that allowed me time to write on the clock: record store, night shift at a Best Western, community college adjunct. Or jobs I thought would give me something to write about: art gallery janitor, medical test volunteer, hazardous waste hauler.

TJW: I really dislike the term autofiction. I think every book is fiction to one degree or another. They’re just stories. I know some of Body High is true, but most of it is fiction (or I think it is). More to the point, there’s the emotional truth under all of it that is more important than the details—the ecstatic truth of your story. It’s like Barry Hannah said, “Literature is the history of the human soul.” What are your thoughts?

JL: I’m not sure I understand the question. Aren’t we already post-autofiction? Last night at a party, an Alt Lit 2.0 writer told me that she hates the word autofiction because “Everything is real.” In essence, the whole world has been autofiction-pilled. Personally, I’m with Barry Hannah. And I think Body High is too. We’re with the human soul. If a writer isn’t constantly reaching inside to touch it, touch the soul, touch the reader, to exhume emotions—fear, love, happiness, disgust—I’m already over it. It’s dead to me. Writing that chooses labels or formalism over inner significance won’t survive.

TJW: I don’t think we are post-anything yet, Jon. I wish, but I’m not convinced that’s the case. When people do something post-autofiction, post-Alt Lit 2.0, postmodernism, post-ninja warrior, it all just gets lumped in with the stuff it’s actively trying not to be.

JL: I have this feeling that we’re post-everything and the only way forward is to look inward.

Troy James Weaver lives in Wichita, Kansas, with his wife and dogs. His work has appeared in New York Tyrant Magazine, The Nervous Breakdown, Lit Hub, The Fanzine, Hobart, and many others. His books are Witchita Stories, Visions, Marigold, Temporal, and Selected Stories.

More Interviews