My First Death Threats | Talking Dogleg with Al Warren and Michael Bible

Interviews

By William Boyle

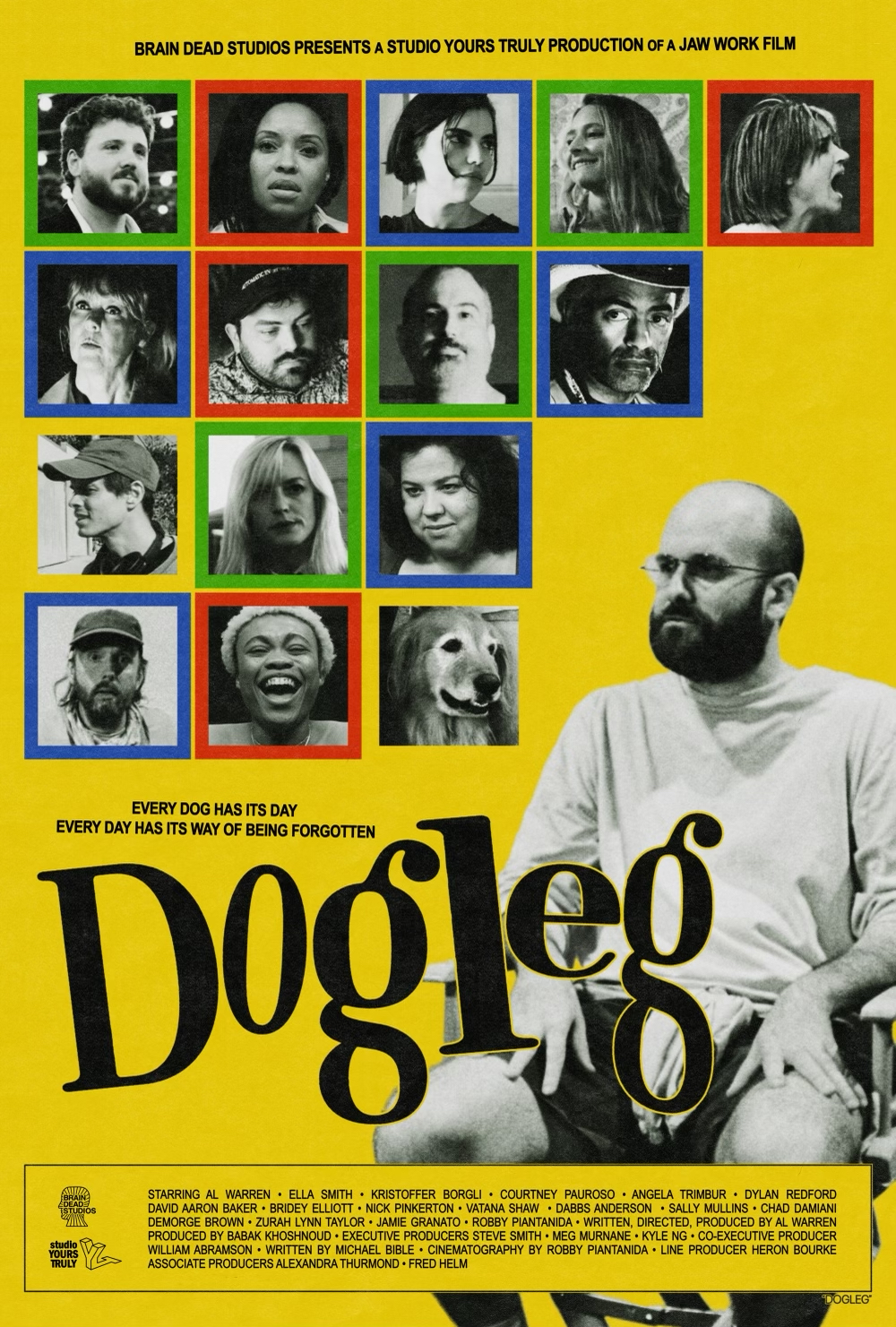

Dogleg is a little wonder of a film. It’s wry, hilarious, and strange. Sometimes reminiscent of John Cassavetes’s films and infused with the spirit of Mr. Show, it also deeply engages with its global cinematic influences.

Dogleg’s protagonist, Alan Warner, is a film director whose girlfriend goes out of town, tasking him with attending their friends’ gender reveal party and caring for her dog. He takes the dog to the party only to lose it after making the mistake of believing the host’s assurances that his yard is fully fenced in. A frantic search ensues even as Warner tries to go through with a planned film shoot. His day is built on weird encounters, producing several instantly classic sequences. The whole thing culminates in Warner becoming completely unhinged on his set. The film simultaneously weaves in shorts that Warner has made and a voiceover conversation with a film critic he admires, yearning for advice and a guiding hand.

Al Warren, who plays Warner, directed Dogleg and co-wrote it with novelist Michael Bible (Sophia, Empire of Light, and The Ancient Hours). Warren and Bible are longtime friends, and their collaboration is rooted in their frequent discussions of film and literature. I spoke with them via Zoom the week after Dogleg premiered in Los Angeles and New York.

WILLIAM BOYLE: I wanted to start by talking a little bit about the origins of the movie, how you started working on it together, and what collaborating on it was like.

AL WARREN: I’m such a huge fan of Michael’s. He’s one of my favorite writers ever and one of my best friends, and I think we’ve been able to cultivate a way of working through these years that now feels pretty worn-in. I think I forced the friendship on him because I really liked his early stuff. At the beginning of 2017, I had an idea. I just wanted to make a movie, and I wanted Michael to be a part of it. We wound up writing a great script, but it was just going to be too expensive for us to make on our own. I saw two paths. Either we could spend ten years in development hell talking with financiers and getting the shit chopped out of our script, or we could pivot and try to write something we could make. Michael was game for that. I don’t want to speak too much for him, but I think he and I had something brewing, and we knew it would happen if we just stuck with it. The tenacity is everything.

You’re a basketball fan, right? I get a lot of energy from watching Kobe videos or hearing how an athlete trains, and I think Michael and I try to bring that kind of mentality to the way we work together. We’ve put up so many shots. We wrote a script that we started to shoot, and we took a look at the footage and sort of called it for what it was. Certain things were great, and certain things weren’t. We just kept chipping away at it.

MICHAEL BIBLE: It’s really funny to hear you describe that, Al, because I definitely think we’ve brought a real seriousness to screenwriting. We worked on it daily for long stretches of time, but it never felt like work to me. It was a great respite from the heavy work of writing fiction that can feel very solitary. Collaboration was freeing. I also knew that Al wasn’t going to judge me if I had a terrible idea, which I had a million of. To me, it’s just goofy fun. Al was here [in New York] for a couple of weeks while we were doing these screenings, and we settled on it feeling like being in the lunchroom when you’re in middle school, just trying to make the other guy laugh. It’s a lot more serious than that, obviously. But that’s the core of it: just goofing around, having fun, trying to make something that we would want to see. We knew that other people might like it if we stayed true to that. That’s the basis of our partnership.

WB: Were you guys in the same place as you were writing Dogleg? Or were you sending stuff back and forth to each other? How did that work?

MB: A lot of it happened over the phone. We would talk through ideas, just riffing and thinking about stuff. One of us would write a first draft. If Al had an idea and wanted to take a shot, he would. Then he’d bounce it to me, and we’d go back and forth, or vice versa. We’re always trading ideas. Like in any other friendship, we’re always sending dumb videos to each other and trying to make each other laugh. Sometimes those things become bits in what we’re working on.

AW: Maybe there was a time when we weren’t utilizing YouTube and Instagram Reels as much as we do now. A lot of what we’re writing is lived experience. But a lot of it is just watching dumb shit and going, “Oh, my gosh, that person’s accent or that person’s way of being is perfect for what we’re building in this script.” I can’t overemphasize how important the Internet is for our process.

WB: Michael, you said fiction is heavy work compared to screenwriting. Had you written for the screen before this? I know you did some stuff for David Milch, but I don’t know much about it. What’s your arc been in screenwriting?

MB: I did a year in LA with David Milch, working with Olivia Milch and a bunch of other great writers. I think of that experience as getting a Ph.D. in screenwriting. Just watching David work was a joy. I’m not sure that I offered a whole lot. We were working on Faulkner. Olivia had gotten a door open to do a script of Light in August, and I was helping her out. Nothing of that time ever saw the light of day. It was exciting and fun, and I learned a lot, but there was also the same frustration Al was talking about. I knew that if I stayed there and climbed that ladder, it would take me a long, long time and that whatever eventually ended up coming out would be way different than I wanted it to be. Working with Al was an opportunity to put out something we really cared about. And no one was going to tell us what to do with it. It was completely, one hundred percent our own thing.

WB: The structure of Dogleg is fascinating. It doesn’t dumb anything down for the audience. It leaves a lot of the work for the audience to do, which is something I really respond to. What and who were some of your influences? (We’ve talked about our mutual love of Hong Sangsoo before. I feel echoes of his work here.) Also, it seems very much like it’s a movie about craft. What were you all thinking about in terms of having this be a movie that focuses on the creation of art?

AW: Michael brings this lightness to me and helps me take things a lot less seriously than I do if I’m writing by myself. He’s really rubbed off on me in that way. I think Michael was just naturally amused by me making things. He became a big part of writing the script and continually revising the film all the way through the edit. We did our first pass of the edit together, which was the first time we’d worked together in a room—we didn’t have the privilege of being in the same town much when we were writing. Michael had this idea that the making of the film would be a part of the film. There are three short films we made in Mississippi that we cut out of Dogleg toward the end of our edit. Those films feature the Alan character directing a lot more than what’s in Dogleg’s final edit. But that was never a part of those original shorts. I tend to do long-ass takes. Michael would be like, “Hold on, run that back. Let me see the way you directed Bobby Rush in that thing. You have something funny there.” We started to lean into that, and I think the process of us talking about filmmaking starts with Michael’s fascination with film and how I’ve tried to make films as an amateur—the things I’m good at, the things I struggle with. Not to just fucking blow smoke up Michael’s ass this whole time, but I think Michael blew the doors wide open on this film. He made it into something more than a collection of standalone shorts based on things we thought were fun to write about. Someone recently asked whether we watch the film back and see anything we’re cringed out about or would do differently. And our answer is absolutely not because we can use that stuff. It’s more of an agreement with ourselves as artists that all of this is good. Even if it’s shitty, it’s useful. Even if we don’t use it in the final cut, it gets us to where the film is. It’s more of a thought process than a goal. It’s more about accepting what the world has given us and working with what we have.

MB: When I was writing in LA, I was very sequestered. I was just writing in a room with people. When I started to talk about working with Al, I felt very ignorant about cinema in general, especially foreign or arthouse cinema. Al pushed me to go deeper. I think there’s freedom in that ignorance. I had to teach myself by watching a lot of movies. But the process of actually shooting something was foreign to me. My expertise is with books and narrative structure, and Al has a lot of experience with filmmaking and acting. We each brought our backgrounds together and tried to learn about the other, and it was really a process of trying different things and seeing what would work.

WB: What else influenced Dogleg—films, literature? Anything that inspired what you were trying to do? Stuff you encountered during the process that informed what you were doing?

AW: We spent so much time on it that we went through different modes. When we started shooting in 2018, we were very into Paul Schrader’s book about transcendental cinema. That book is a study of Ozu, Bresson, and Carl Dreyer. At some point, we started to get really into comedy. We got deep into certain kinds of humor that weren’t the run-of-the-mill American thing. We were watching Roy Andersson, Ruben Östlund, Yorgos Lanthimos, and even weirder, off-beat stuff. They’re just comedies to us, but to a lot of American moviegoers, they might seem a little exotic or something. I didn’t go to film school, so I made a commitment in my early twenties that I would always try to be a student of film. The book Cassavetes on Cassavetes is my Bible for DIY filmmaking. John Cassavetes—his attitude, his spirit—lives on in what we’re doing, I hope. I love Eric Rohmer’s stuff. It’s not necessarily funny, but it’s got an element of comedy in it. There’s a style to it, a brevity to it, that Michael and I both really enjoy. We were lucky to find each other because we like a similar type of cinema, a similar type of joke, a similar type of person or actor or story. We don’t really divert too much in our taste, and when we do, it’s kind of fun to see where those diversions happen. Anything I’m forgetting, Michael?

MB: Hong Sangsoo was definitely a big one, but we also talked about people like Steve Coogan, a lot of that really dry British stuff.

AW: Buster Keaton.

MB: Yeah, the old deadpan thing. He was the originator of all that. Also, Billy Wilder movies. I feel like Al is a master of that kind of comedy. There’s a big difference between the types of comedies he’s talking about. I don’t know if it breaks down like this exactly, but there’s wet and dry. A lot of American humor is very saucy, and there’s a lot of spice or sugar in it. It’s overprocessed and overthought. A lot of British humor, European humor, or even Korean and Japanese humor is much more subdued and laidback. You’re being asked to do a little bit more to get the joke, and we really like that. Al is great at that deadpan, not breaking, not laughing or winking at the camera, committing completely to the bit. It’s not just about a funny voice. Early on, when I was living in Oxford and Al was still in Jackson, we’d call him in the middle of the night if we were at a party and tell everyone to shut up and put the phone through the computer onto a speaker and make him do prank calls to Waffle House or bail bond agents. It was the funniest shit I’ve ever heard in my life.

WB: Hong Sangsoo often features a filmmaker as major character, but were there other films about filmmaking that influenced you? Dogleg made me think about Tom DiCillo’s Living in Oblivion and Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie.

MB: You always say Truffaut’s Day for Night, Al. Abbas Kiarostami was another director we discussed. All of his movies, but certainly Taste of Cherry. Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool was a film we talked about a lot—the documentary element, the film-within-a-film thing. But there’s also Shakespeare and his plays-within-a-play. There’s a whole tradition of literature about literature: Don Quixote, these metanarratives about the creative process, the creative act. But I don’t think that that was something we led with. I don’t think we were immediately thinking, “Oh, we’ll make a movie about a guy making a movie.” Al does tend to write about that stuff because it’s right at hand. That’s probably why Hong Sangsoo does it, too.

AW: Day for Night and Contempt were real north stars for us on how to do it. I appreciate you saying what you said at the top about our relationship with the audience. We never want to talk down to an audience, but we know we’re going to lose people because the current climate is all about spoonfeeding. Distancing the audience is important in transcendental cinema. For example, when Ozu doesn’t move the camera or doesn’t include many cuts in a scene. There’s this thing that can happen when you’re in the theater watching those films. You feel unsure. I don’t know if we’re trying to do that so much with the camera anymore, but we want to do that with the comedy. We’d rather throw you into the deep end and watch you swim to the shore than reel you in.

MB: Steve Martin used to talk about how he would go see stand-up comics, and everything was so overwritten that audiences would know where to laugh. That wasn’t nearly as funny to him as when he was just having fun with his friends. He tried to unpack why. It was because you had to be there. He put together an act that was about that: you just had to be there. I like the idea of trying to create a mood. We’ve experienced this at a few screenings: people laughing at strange parts of the movie. But that’s the most satisfying kind of laugh. They’re not laughing at a joke necessarily, or a beat that’s supposed to be funny. They’re just laughing at the whole mood. What the hell is going on with this thing? This guy’s got himself into this ridiculous situation. Those are the things I find the funniest, not when you’re hitting a punchline. You’re laughing at the premise.

WB: Dogleg is built on conversations and encounters, which is something I love. That scene of Alan freaking out on his crew is a great comic crescendo. You probably know this already, but I saw that scene in a Reel on Instagram, totally out of context, and other people were commenting on it as if it had happened in real life. What was filming that scene like? Was it all written? Was any of it improvised?

AW: I’m not like that when I work. I’ve never done that. At the same time, I’m an emotional dude. I don’t think I’m erratic. I try not to be, but our producer Bob’s seen me get heated. And he said he just wanted to see the Alan character blow the fuck up. Michael and I thought that was a great idea. I’m proud of that scene. We wrote it line by line, then distilled it into a script that freed the actors and crew from having to hit these strict beats. The beats were contingent on the Alan character, so I could get in there, play Alan, and direct simultaneously.

I remember the day of the shoot being really fun but also stressful. It was hot, and the light was completely red. It felt like hell in a funny way. I encouraged the crew who weren’t essential to the confrontation to pull out their phones and film it. If it felt natural for them to do that, they could. One guy on the camera crew pulled his phone out and filmed one of the takes—not the take that’s in the movie. He showed it to me after we wrapped and said we should use it to promote the movie. I thought that was a great idea. That was two years ago. This is a guy who’s not a regular member of my film team, so I don’t have close communication with him. I was in Italy in April for a job when he sent it to me. He’d posted it with no context. He has forty-five thousand followers. It started to get passed around to these different movie meme accounts and Reddit threads. Joe Russo posted it on Twitter and wrote, “Whatever you do, don’t act like this asshole,” or something like that. The comments were so funny. Last week, we shot a fake apology. It’s a video with this actor who’s supposedly interviewing me for Good Morning, America. It’s been a little gift to the marketing of the film. We gained a lot of audience members who were made curious by it. And I’m kind of a troll by nature. Michael mentioned the prank calls—I like that heat. I’ve gotten my first death threats from this. There’s a whole slew of comments where people are like, “Fuck this guy.” Then someone will say, “Oh, that’s actually Al Warren, who I know. He’s a sweet guy, and this is from his movie Dogleg.” And most of the people will be like, “Oh, shit, I’ll check it out.” And then there’s a handful of people that’ll stand their ground, and they’re like, “Fuck this guy. I don’t care if this is a fake thing. You should never act like this on set. This guy shouldn’t ever act again.” Personally, I love that shit.

WB: I love that scene where the woman witnesses Alan almost getting hit by a car, takes him home, and reveals herself to him. Who’s that actor?

AW: She’s a comedian and adult film star named Sally Mullins. When I was casting that role, I’d tell anyone auditioning that we were a respectful film team, and we weren’t going to ask them to actually reveal their naked bodies. Most of the actors were very happy to hear that. Then I met Sally. She liked the script, and I liked her work as a comedian. When I got to that part of the conversation, she told me, “Al, I’m a porn star. I have an excellent body. If I don’t do that, then I’m doing a disservice to my work. So, if I do this, I want to be naked in that scene.” There was a lot of excitement on the set the day we filmed that scene. I was very curious to see how it would all go down. That performance, my reaction to seeing her, is real. We just got really lucky.

MB: We’ve created a process of working where we’re really interested in taking what’s behind the camera and somehow putting it in front of the camera. As we start to write new things (or the next thing), we really do bow down to the universe. There’s a lot of filmmaking that tries to eliminate mistakes. A lot of musicians do that, too, and novelists who try to make this cut diamond, this sort of perfect polished stone. To us, letting those mistakes and flaws be—and overcoming them, finding a way around them—is really what the creative process is about. Embracing the mistakes and not trying to scrub them out. That, to me, is where the excitement comes from. We weren’t interested in showing nudity or depicting graphic sexual things or any of that. But the fact that we found someone willing to do something like that pushed us to try and think about it in a different way. Whenever we encountered something that wasn’t a smooth road, we had to improvise, and that’s what makes it fun. How things can be surprising on set. That’s the spirit I’ve come out of Dogleg with, and it informs certain things that I do in fiction now, too. I’m not afraid of something not being completely perfect. I like imperfection. I like things that aren’t ready-made and served up for you. That’s the more human thing.

AW: Michael really turned that on in me. His ability to be happy with what the world is giving him—that wasn’t my natural mode. I’ve worked on a lot of commercial projects where that’s not the game you’re playing at all, and that was beaten into me. If you’re working as a commercial director, that’s going to happen. You’re collaborative in a different way. You’ve got a brand to serve. We don’t have a brand to serve. The brand we serve is a spirit or a faith or a belief in something that might not be right in front of us, and when something happens that we’re amused by, that becomes the thing. I credit Michael for turning that on in me as a writer, director, and actor. I like acting because I get to practice a technique that allows me to be in a play for a hundred days in a row and, on that one-hundredth performance, I can still find things that are happening tonight, and happened on my walk to the theater, and happened in my day, or right here, right now—like the way that you just muted to cough—I can use anything that’s happening, whether or not it was scripted. I can use that for the character. It’s a whole new way of being that still feels fresh to me, and it feels like what I was always meant to be doing. You can see that in Michael’s work as a fiction writer. There’s a freedom there. I want to always incorporate that into whatever I’m doing.

MB: When I was a kid, I wasn’t very interested in perfection. I never really had that sense of perfection as a musician or a visual artist. Early on, somebody told me, “You can try to draw a house and get it perfect. Or you just scribble a bunch and find the house within it.” I’ve always had a feel for improvisation. A lot of times, it doesn’t work. You’ve gotta be comfortable looking back at things you’ve written and admitting they sucked. But nothing’s better than that feeling of having something surprise you, because if I had to be creative, and I wasn’t surprised by things, it would get really fucking boring. If Al and I worked in a way where we fussed with the lights and we worried about every tiny little thing, or each syllable’s gotta be exactly right when the actor says it, it wouldn’t be fun. Al challenges me to create work that will stay fresh and fun for him to film and act. The goal is that everything becomes potential material. That anything can become the story.

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, City of Margins, and Shoot the Moonlight Out, all available from Pegasus Crime. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

More Interviews