Desire and Its Objects | A Conversation with Madelaine Lucas

Interviews

By Zach Davidson

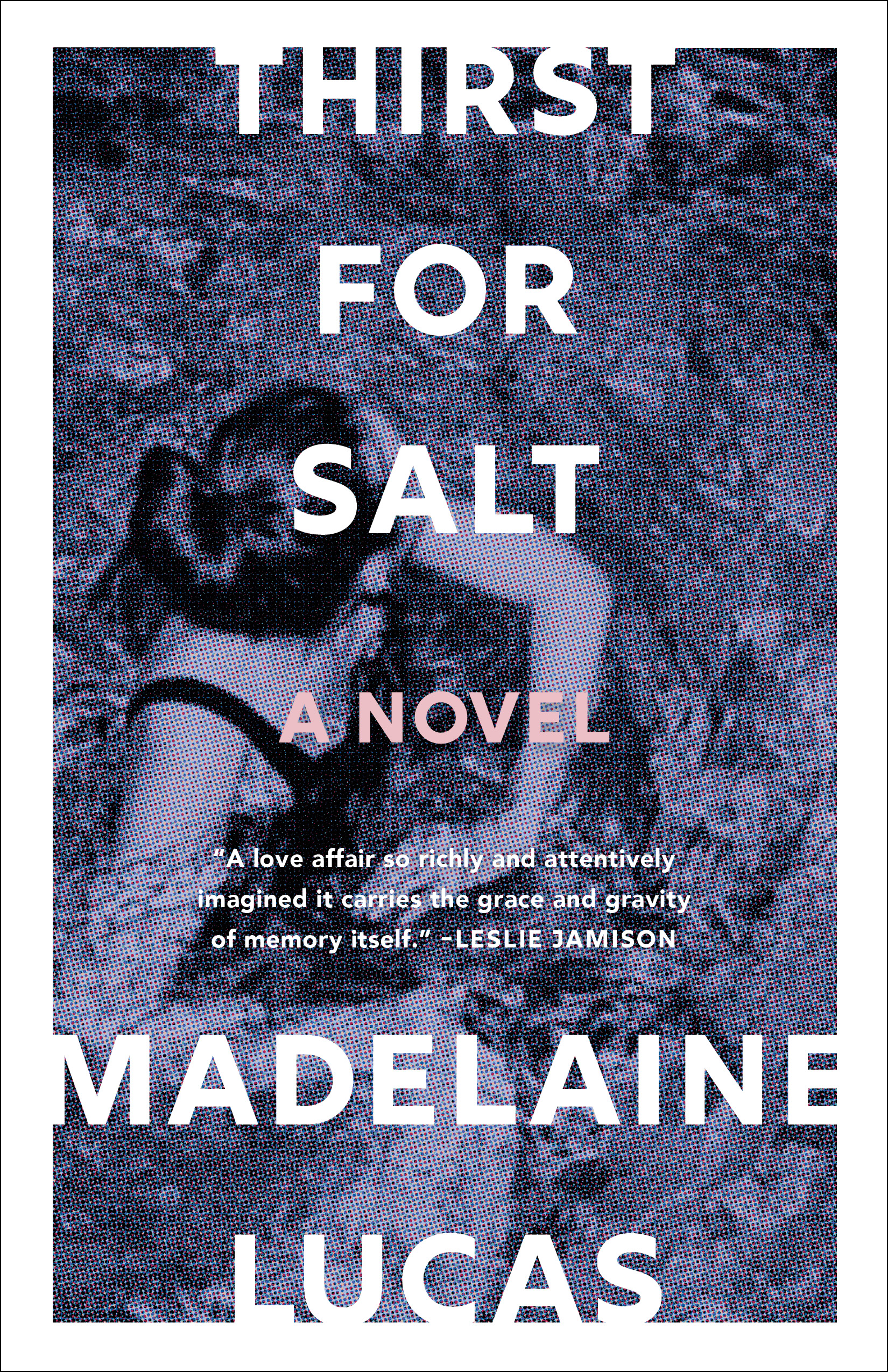

Madelaine Lucas’ debut novel Thirst for Salt (Tin House) investigates desire and its objects. How the former may constitute the latter—is desire itself what is desired?—is just one of the concerns that the book’s unnamed first-person narrator seeks to unpack. Unpack, for, as the narrator’s mother asks in reference to her daughter’s past (including her reminiscences of Jude, the novel’s focal bygone love), “Why carry all that around with you?”

Without a zipper on the side of one’s head to conveniently empty one’s mind, it’s only natural for us to convey our memories, whether regrettable or not, to the present. But if, as Thirst for Salt’s narrator asserts, “I need to find a place to put it all down,” how does one do that? And what does that achieve—can the words on the page ever contain the life lived?

Probably not. Yet perhaps that necessary variance between life and writing is what motivates the writer’s and the narrator’s project in the first place. As Lucas writes, “It never really goes away, the longing for the life not lived, because isn’t that part of how we come to know ourselves too? Through what we lack as much as what we have, all we dream but do not hold. Some desires have no resolution.”

As senior editors of the literary annual NOON, I’ve known Madelaine for several years. I interviewed her over email about Thirst for Salt, asking her to elaborate on the desires and objects that form it.

Zach Davidson: Thirst for Salt opens with an image that instigates the narrative: “Today I saw a picture of Jude with a child.” A photograph and a drawing, including Joy Hester’s poignant Two sunken lovers bodies lay, also receive particular attention in your novel. Can you talk about how your own personal experiences of images inspire your storytelling?

Madelaine Lucas: I grew up surrounded by my mother’s paintings, which occupied the walls of our home, so visual art has been a part of my intimate world and an influence on my imagination for as long as I can remember. My mother’s artwork has an autobiographical element to it—it draws from her personal experience, but it also transfigures it into something that has a greater symbolic meaning or value. I think I try to do something similar by writing fiction.

Joy Hester is one of my mother’s favorite artists, and while I was familiar with her paintings, I encountered that drawing by chance in the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney while I was working on the novel. There was an immediate, uncanny sense of recognition—the man and woman holding each other against the rough peaks of waves, which could also be reminiscent of the shape of an A-frame house, reminded me of Thirst for Salt. So I put the reference in. Just like you might quote a line from a poem, it was another way to add thematic resonance to the book. There are references to other artworks in the novel, too, including a description of Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece, which came about as the result of an early workshop conversation when I was studying with Heidi Julavits, who mentioned it in connection with one of my stories as an example of how passivity can also be a way of accessing power. The character of Maeve was also initially drawn from a Nan Goldin photograph of a dark-haired woman with a lot of silver rings on her fingers, smoking a cigarette.

As a writer, I feel both inspired by and a little envious of the way visual art can communicate feeling in a way that isn’t mediated by language. I think this is partly why images seem to speak so strongly to my subconscious.

ZD: Houses—and our ideas of houses—are not static in Thirst for Salt. The narrator, on account of her mother’s “wandering eye for a Victorian terrace, or an aging Australian bungalow built in the California style,” is treated to an itinerant upbringing. Jude’s A-frame is the site of love and destruction. Your novel suggests houses are as much characters (the Old House) as characters are houses (as the narrator says, “If Jude was a house, I sensed that he held many hidden rooms.”). In what ways was writing this book like building a house? Did editing resemble “ripping up a garden gone to seed, peeling back flaking wallpaper, stripping the paint from the floors to reveal a dusty golden pine or wide boards of solid Tasmanian oak?”

ML: Years ago, when I first had the idea that would eventually become this novel, I read Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space and was taken by his description of “the home of other days” as a “great image of lost intimacy.” Like my narrator, my parents divorced when I was very young, and we all moved house frequently during my childhood. On one hand, this taught me that “home” was not a fixed or stable thing. On the other, I learned to see home as something that could be broken down and remade again and again—a creative act, in other words.

Destruction—or deconstruction—and reinvention are also part of the artmaking process, and I do think there is a connection, as you insightfully suggested, between the act of renovating and editing, especially of the kind we do at NOON. I first envisioned this book as a linked story collection, a form I love and deeply admire. But to continue with the book-as-house metaphor, I started to feel like the parts of the narrative were too neatly contained in these separate rooms. It needed more space—and yes, maybe more air. So, the most significant aspect of the revision process involved breaking down my original drafts for parts and salvaging what I could. I am a big believer in “recycling” and think often of what Diane [Williams] says about how no good language should be wasted because it’s always so hard-won. From that point on, it was a slow and laborious process of building the novel sentence by sentence. Apart from a rough sense of what parts of the original stories should go in what order, I didn’t have an outline and didn’t know what the final shape would be until very late in the process. Needless to say, I wouldn’t recommend building a house this way!

ZD: How does the intimate, physical environment of the house—the home—shape your writing? I’m thinking, in part, about what Maya Angelou said: “I try to keep home very pretty, and I can’t work in a pretty surrounding. It throws me.” (She added: “I keep a hotel room in which I do my work—a tiny, mean room with just a bed, and sometimes, if I can find it, a face basin.”) Do you write differently in different rooms? Do you seek out certain types of spaces in which to write?

ML: I’ve lived in the same apartment for seven years—longer than I’ve lived anywhere else—and that stability was the most valuable thing while I was working on the novel. I could immerse myself in a long-term project because I knew that I wouldn’t have to uproot and that I could easily access my drafts (which I always print and mark up by hand) and whatever books I might want to reference. Also, early parts of the revision process involved cutting my drafts into pieces and rearranging them on the floor, so the manuscript wasn’t that easily transportable. For these reasons, I don’t work well outside my apartment. There are also too many external factors you can’t control in a space that isn’t your own, like what music is playing in the background. Of course, there’s a risk when working from home of getting distracted by tasks that might on the surface feel more “productive” than writing. But I’ve found that it’s often when I take a break to make a cup of tea and find myself unloading the dishwasher that my ideas come together.

Your questions have also made me think about the fact that I was raised by two working artists—a painter and a musician—who had to work out of whatever space we were living in because there wasn’t extra money for renting studios or to pay for childcare. I think growing up this way has made me see a connection between creativity and domesticity; this might be why I see art as something that comes from within the home.

ZD: In Thirst for Salt, time and its relationship to desire is expressed evocatively. How have your desires as a writer changed over time? Did you have any specific desires for this book?

ML: One of my intentions with Thirst for Salt was to find a way of writing that could express different experiences of desire, from an ambient longing for the life not lived to the kind that has an immediate, electric charge in the moment. It felt important to place my narrator at the center of this, as I think our culture still treats women’s desires as unserious or trivial. But the tricky thing about trying to write about desire is that it isn’t static, either. Our desires are fluid and changeable. As the narrator says, “our dreams like our memories aren’t immune to revision.”

Similarly, my desires or ambitions for this novel changed over time. Because I came to writing the novel via short fiction, I had the idea I could make the book as “perfect” and polished on a sentence level as a story—something very few novels achieve. But, under this scrutiny, the prose became overworked, and the story flatlined. After one particularly brutal revision, I realized that my obsession with making something “perfect” was sacrificing the spontaneity and vulnerability: the magic. So, as humbling as it was, I had to release myself from the standards I’d set. What mattered most in the end was that I tried my best to articulate something that felt true to me, and in the hope that it might also resonate with others. My most earnest desire for the book is that it finds its way to those readers, and, beyond that, that I can continue to do this work and build a life as a writer that is sustainable.

ZD: In the 2023 issue of NOON, the editors discuss “the excitement of influence” with Christine Schutt. What stories or books had the greatest influence on the writing of Thirst for Salt? And did you experience this influence as exciting, invigorating, and/or as something else?

ML: To me, it’s always invigorating! I’ve never understood people who say they don’t read when they’re writing because they don’t want to be influenced. I’m the opposite. I want to steep myself in work that feels close to what I want to make and to invite those other voices into my head. I trust that whatever I pick up will eventually drift down into the silt of my mind and merge with all my other experiences, lived or imagined, and come out on the page reprocessed as something new. But I also don’t know that I’m that interested in originality or novelty. I think there’s something beautiful about those resonances existing within a work, and the way it allows different artists to connect with each other across time, as we discussed in our NOON feature.

Speaking of Christine, her book Florida was an early influence. It’s one of those rare novels that sustains the attention to language that I love about the form of the short story. I also reread Sara Majka’s story collection Cities I’ve Never Lived In several times while writing Thirst for Salt to revisit their beautifully distilled truths and isolated, wintery landscapes. Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson revealed something that I’d felt but never seen articulated about the way absence, transience, and longing shapes the way a person inhabits the world. Garth Greenwell’s Cleanness showed me a way of writing about sexuality that was both intellectual and carnal at once. Rachel Cusk, Yuko Tsushima, and Helen Garner provided inspiration in their varied depictions of motherhood and domestic life. To a certain degree, I feel a first novel is influenced in some way by everything you’ve ever read, watched, listened to, dreamed, or witnessed, so there were many others along the way, but those are the writers I particularly wanted to feel myself in conversation with while I was working on Thirst for Salt.

ZD: At one point in the novel, the narrator expresses a need for “guidance . . . structure.” She reminisces about when time had “a recognizable shape.” How would you describe the process of achieving a shape—a structure—for your novel?

ML: I have a worrisome theory that the things that trouble us as writers are the same things we struggle with as people. For me, structure has often felt elusive. Perhaps because I started writing short stories, or because of our work at NOON, I think in images and sentences more than I do in plot points, so I struggled to picture the larger shape of the novel until the very final draft. I always knew the middle would follow the arc of the narrator’s relationship with Jude, but since the story is told retrospectively, the biggest challenge was figuring out where the narrator was in her life in her present when she’s looking back on their time together. The classic workshop question, “Why is this story being told now?” frustrated me. Who really knows how memory works and why the past comes back to us in the way it does? These are the things I was trying to figure out by writing the novel in the first place! But for the sake of narrative urgency, there needed to be a trigger, and it was hard to find one that didn’t feel artificial. The opening description of the photograph of Jude with a child originally came toward the end of the book. It was one of my favorite passages—one I’d written purely for pleasure—so I thought, “What would happen if I began with one of the images I felt was the strongest?” I also drew a lot of inspiration from the way Marguerite Duras deals with memory in The Lover, which also opens with a description of a photograph (albeit an imaginary one). I liked that there would be a resonance between those two beginnings.

ZD: In the acknowledgments, you thank Elissa Schappell “for telling me I didn’t need permission.” As mentioned, you, too, are a teacher of writing. Can you say more about the idea of permission as it relates to writing, both as teacher and practitioner?

ML: When I was in workshop with Elissa Schappell, she would often tell us to stop waiting for the world to give us permission to write and insist that only we could give that to ourselves—which, if I am remembering correctly, was advice she was given by Toni Morrison when she worked at The Paris Review. There’s a tendency in writing circles for people to use “permission-giving” as a kind of shorthand for certain books or authors that reveal a freedom of expression they didn’t know was possible before. I understand this, but I think Elissa and Toni Morrison are right—we shouldn’t give other people this power over us, no matter how much we admire them. So, perhaps it’s more helpful to think about looking to other writers for courage and guidance, which is what I hope to give my own students.

Zach Davidson is a senior editor of NOON and a frequent contributor to BOMB.

More Interviews