On Family Album | A Conversation with Gabriela Alemán

Interviews

By Mary Ellen Fieweger and Dick Cluster

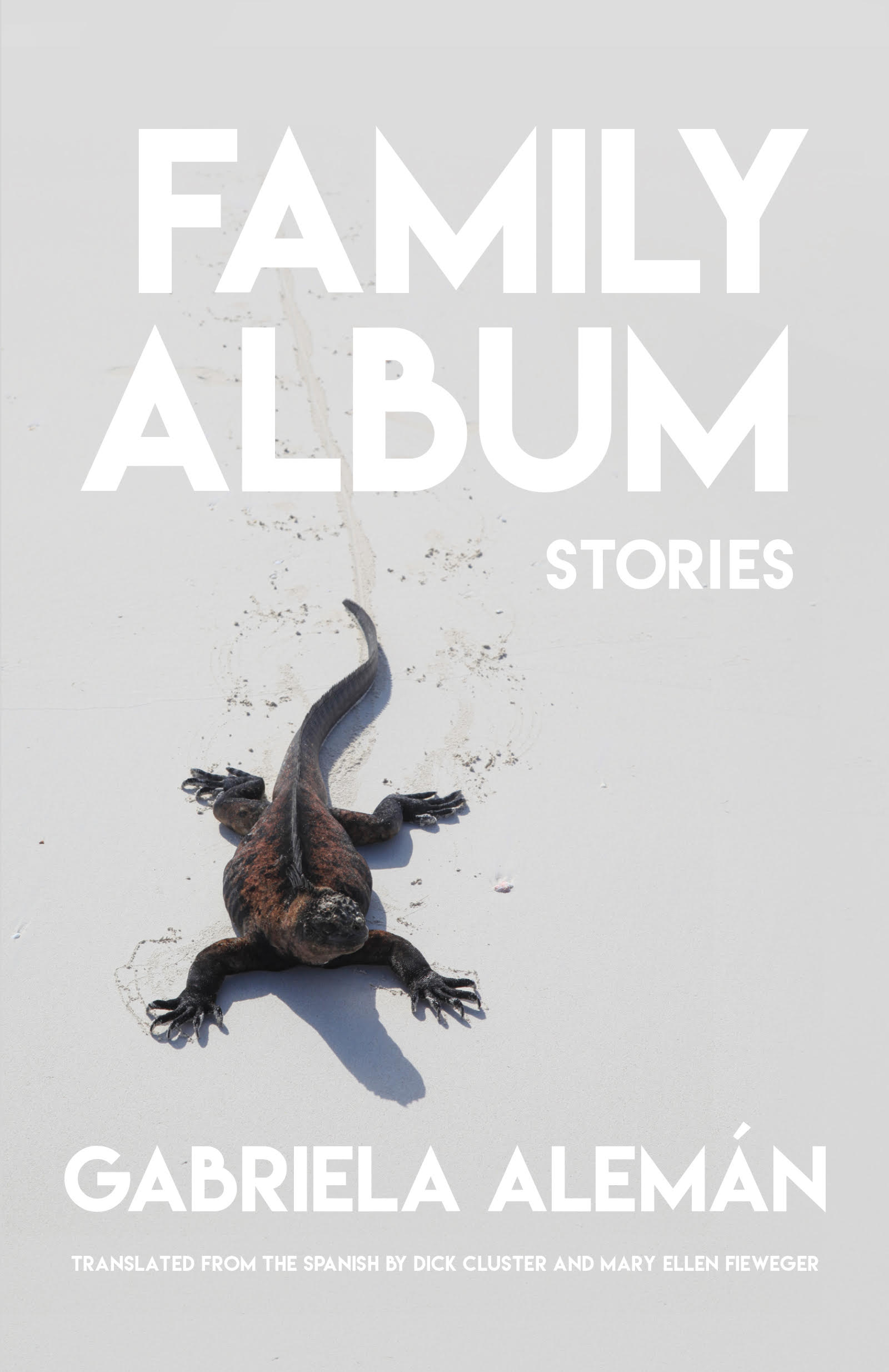

Gabriela Alemán is an Ecuadorian novelist, short-story writer, and journalist, born in 1969 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She has also played professional basketball in Switzerland and Paraguay and has worked as a waitress, administrator, translator, radio scriptwriter, and teacher. Her first book translated into English, Poso Wells, was published in 2018 by City Lights Books. It is now followed by the story collection Family Album, which teases tropes of hardboiled detective fiction, satire, and adventure narratives to recast the discussion of Ecuadorian national identity. From a pair of deep-sea divers looking for sunken treasure in the Galápagos Archipelago, to a hired gun accompanying a group of missionaries into the territory of the indigenous people of the Amazon, this series of cracked “family portraits” serves up a cast of picaresque heroes and anti-heroes in stories that sneak up on a reader before they know what’s happened.

Here is a conversation with Alemán and the two translators of these sometimes whimsical, sometimes terrifying portraits.

Mary Ellen Fieweger: If the Alemán family is any indication, writing would seem to be an autosomal recessive disease, i.e., one that affects every other generation. Gabriela is the granddaughter of Hugo Alemán, one of his generation’s best-known poets and a founder of Ecuador’s Socialist Party. There were no writers in her dad’s generation. Mario was a member of Ecuador’s diplomatic corps and, as such, Ambassador Alemán helped me sort out a number of sticky situations. My link here, both to the ambassador and to Gabriela, is her brother, Álvaro, also a writer and, back then, a student in the Honors English course I taught at Colegio Americano. Álvaro was an English teacher’s dream; he loved reading and writing, and we became and have remained friends. In subsequent years, when people visited from the States, I often invited Álvaro to join us. Sometimes his younger sister tagged along. I remember her as the little fly on the wall at our gatherings, saying nothing, observing everything.

Our first formal engagement was when Gabriela asked me to write the introduction to her Master’s thesis, an analysis of how women are represented in Ecuadorian literature of the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. That was in 1994. Lorena Bobbitt, the Ecuadorian woman married to John Wayne Bobbitt, a U.S. Marine Corps vet, was on trial for slicing off her abusive husband’s penis after he came home drunk and, yet again, raped her. In that introduction, I pointed out the significance of Gabriela’s analysis given that Ecuador’s male writers—and the vast, vast majority of published writers in the country back then were male—continued to have a very skewed view of women, explaining, by way of example, how Ecuador’s male journalists handled the Bobbitt case at super-long arm’s length. That is, in geopolitical terms: North versus South, tiny Third World manicurist versus brawny First World ex-Marine, an extraordinary approach to violence that took place in the intimacy of the couple’s bedroom.

All of which—growing up in the various countries to which her dad was posted, being of a seriously observant nature, and being a woman in a profession dominated by men until very recently in Ecuador—are phenomena that must have something to do with the spectacular writer she has become and which I address (albeit obliquely in some cases) in the questions that follow.

Dick Cluster: I met Gabriela quite a bit later than Mary Ellen, at a presentation of the Cuban edition of her novel Poso Wells at the 2014 Havana Book Fair, where Ecuador was the featured country. One thing led to another, and finally to my translating that book for City Lights. Next, I asked to see some of her stories. She sent me a group from Álbum de familia (Family Album), one of them featuring a woman in Buenos Aires who meets John Wayne Bobbitt, not knowing who he is. I found these shorter pieces displayed the same kind of madcap juxtapositions and use of multiple genres she’d displayed in the novel, but in strikingly different ways. I was also struck by how, in this variegated collection, Ecuador always pops up somewhere, whether the action occurs in the Galapagos, Argentina, Mexico, Venezuela, or Brooklyn. My questions take off from those observations.

Mary Ellen Fieweger: Because your dad was a diplomat, you grew up in more countries than most people visit in a lifetime. You have continued to move about since then. How have these long-term stays in countries other than your own affected your writing?

Gabriela Alemán: My guess is—because I don’t know how it would have been had I not moved around so much—that living in so many countries put me in contact with a variety of literary traditions from a very young age and, because I speak a number of languages, the ability to think in those languages while I write in Spanish.

Dick Cluster: With most writers I’ve translated, I’ve felt they were “really novelists” or “really short story writers,” even if they do venture into both terrains. In my own work, I feel that I know (sometimes) how to write a novel, but not how to write a story. You’re really skillful at both. What can you tell us about your experiences in the two genres, and what has led you to each?

Gabriela Alemán: The difference mostly stems from what I want to write about and how much information I have or what suits the story better. I’ve written a 300-page novel only to realize, while editing, that there could be a good fifty-page novella or a long short story in there, so I got rid of the 250 odd pages and worked on those fifty. Something like that happened with one of the stories from another short-story collection: La muerte silba un blues (Death Whistles the Blues).

In the case of Family Album, there are real events behind all of the stories. I had been obsessed with, or at least knew of, these events thanks to journalistic pieces I wrote, family lore, or archival work. At some point, it just seemed natural to think up a book that put all those stories together. When the book came out in Colombia, a reviewer said they could also be read as chapters of a novel “about” Ecuador.

I’ve written three novels (Poso Wells, Body Time, and Humo/Smoke) and five collections of short stories. With each of those books, I never set out thinking it was going to be a short story collection or a novel. I just started writing until I was able to see what would work better for the story. Poso Wells had too many characters and locations to work as a short story, for example. And, while the story in Family Album about Biddy Basketball (“School Trip”) could potentially have a lot of characters, the story I wanted to tell centered not on the championship itself but on two people talking about that championship many years later. So it worked better as a short story. On a side note, I am now writing a novel that has a lot to do with basketball, and that story is coming back in a different, expanded form.

Dick Cluster: In Family Album, while the stories are completely self-contained, there’s that linkage in the form of Ecuador always lurking somewhere in the background or foreground. Also, you’ve titled the stories as if these were captions in a family photo album. Meanwhile, Mary Ellen and I have been translating the stories in the other collection you just mentioned, Death Whistles the Blues, in which characters and incidents do sometimes overlap. When you find yourself writing stories, how do the groupings and linkages come about?

Gabriela Alemán: Those two books are very different in how they were conceived, their tone, and their content. When I wrote Family Album, I wanted the book to have the feel of a photo album (something that had begun to disappear from people’s homes). From the beginning, I had thought up the title with the idea that the “frame” of the photograph or story was always going to be Ecuador, while the image “inside” was going to be the story I wanted to tell. And each story had a specific genre it was going to belong to (adventure, thriller, detective, dark comedy, etc.), so its tone was dependent on that.

With Death Whistles the Blues, the tone was set around the movies made by the Spanish director Jess Franco—gore, softcore porn, B movies—as were the titles of each story, which all came from his movies. That made the collection much darker than Family Album. Also, Franco would make movies on a very tight budget and try to get two or three movies out of one. He would not give whole screenplays to his actors, only dole out the pieces on a daily basis so as to give them two or three scripts instead of one, as the films were not shot following a chronological order. Generally, those different films were set in very different places geographically, although their underlying tone made them feel part of a unit. By adhering to Franco’s production model, I had the same “characters” jump in time (there are stories set in the 1930s, the 1940s, and the second decade of the twenty-first century) and locations (Ecuador, New Orleans, the border between Paraguay and Brazil, Mexico City).

Mary Ellen Fieweger: In a number of your stories in both La muerte silba un blues and Álbum de familia, the protagonist is an old man. Three stories come to mind: “El diabólico Dr. Z” (“Homework”), “Bautizo” (“Baptism”), and “La muerte silba un blues” (“Jam Session”). What is it about old men that inspires you to write these incredibly moving stories?

Gabriela Alemán: I think it’s because of the way that the world works. Men, in general, have a bigger dose of self-confidence than women do and, when time passes and the fragility and uncertainty of old age arrive, men find themselves in a much more vulnerable place than do women. That lack of certainties, or the collapse of those certainties that had existed, opens spaces I find interesting to explore.

Mary Ellen Fieweger: In addition to being a prolific and successful writer, you have devoted yourself to the promotion of Ecuadorian and Latin American literature both here in Ecuador and in the U.S. In 2009, you organized the Quito book fair. As I write these words, you are in New Orleans, at Tulane University, where you are responsible for the Latin American Writers Series, a digital archive that includes interviews, story maps, timelines, readings, and materials donated by the writers and which you helped create. Tell us about how you got involved in this work and why you do it.

Gabriela Alemán: My mother was a teacher who worked in the public primary and high school system. Growing up, I saw first-hand how little support teachers have: no funding, no time to prepare new curricula, and few, deficient, or no libraries. The digital archive at Tulane is a way to help teachers, students, and the general public access materials that are hard to come by (especially in Latin America), so they can teach/come into contact with contemporary Latin American literature. Because of the way the archive is set up, the students can make the connection between those authors and their contexts and literary traditions. The authors interviewed aren’t the only ones featured. When the authors talk about their influences and their reading life, I embed in their “timelines” long interviews with or documentaries about Juan Rulfo, Clarice Lispector, Blanca Varela, et cetera. Each author is also representative of a movement or genre being explored at the moment: post-conflict writing, Gothic fiction, neo-detective fiction, autofiction. In these days, when everything seems to exist in a void, the digital archive is a way of tying the past with the ever-fleeting present.

The Ecuadorian literary tradition seems to be more criticized than read in Ecuador and that is why El Fakir (the book publisher I am part of and helped found) came into being. There are few publishing houses in Ecuador, and even fewer that were interested in republishing old texts or “transforming” those texts into genres that could gain new readers. For example, we have a graphic novel and comics collection, and, in collaboration with Carlos Villareal Kwasek, I have adapted two stories by César Dávila Andrade into comic book format. We are looking to attract teenage readers who will eventually read other types of literary texts.

When I set out to curate the Quito Book Fair, I was thinking of readers and how they come into contact with books. We published three booklets with texts (short stories, poetry, and essays) by the authors who participated in the book fair. These booklets were distributed free of charge to people who attended the events. At the fair, there were exhibits and events about and by indigenous writers, parents (writers) and their children talking about books, magazine editors, poetry, different generations of authors from the same country talking about their books, among others.

Dick Cluster: You’ve mentioned the historical kernels of the stories in Family Album, which include German settlers in the Galapagos in “Summer Vacation,” the international youth basketball competition in “School Trip,” and the deaths of a group of U.S. missionaries in the Amazon in the 1950s in “Family Outing.” Humo (Smoke), which I’ve been translating over the past year, is very much about the history of Paraguay. What is it that you like about taking such kernels of the past and teasing out a story—or however you’d describe what you do?

Gabriela Alemán: I like the “behind the scenes” quality of it. I like trying to tease out motives and intentions from episodes where we were not privy to those. I like to understand the past without the burden of imposing our present mores on it. And I love archival work. I have a problem with the discourse around how the “present” understands things in the right way. For example, I love discovering how a number of Utopian societies were founded in nineteenth century Paraguay—as was a nightmarish town claiming to rekindle a purer Germany outside of Germany. Nueva Germania was founded by Nietzsche’s sister and her husband there.

Mary Ellen Fieweger: I’ve translated two anthologies of stories by Ecuadorian writers. The first, Ten Stories from Ecuador (1990), included not a single work by a woman. When I asked the writer who chose the stories why not, he said—and I’m paraphrasing here—because they (i.e., women) concentrate on interior matters and readers (who are always and everywhere male, presumably) are not interested in that sort of stuff. Of the twenty-seven works in Contemporary Ecuadorian Short Stories (2016), six are by women. What has it been like being a woman in a profession dominated by men, and what changes have you seen over the years?

Gabriela Alemán: I’ve never considered writing my profession (but, rather, something I do) and tend not to worry too much about the extraliterary life of meetings, conferences, and get-togethers dominated by male writers. If I would have paid attention to all the disparagement that was going on when I started to publish, I would have stopped writing a long time ago. Alas, I did not.

Dick Cluster’s other translated books include works by Cuban authors Mylene Fernández Pintado, Pedro de Jesús, Aida Bahr, Abel Prieto, and Antonio Jose Ponte, Mexican poet Paula Abramo, and the anthology Kill the Ámpaya: The Best Latin American Baseball Fiction. He is the author of the novels Return to Sender, Repulse Monkey, and Obligations of the Bone and of a social history of Havana. Cluster lives in Oakland, California.

Mary Ellen Fieweger has translated books by Abdón Ubidia and Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo, and two anthologies of short stories by Ecuadorian writers: Ten Stories from Ecuador/Diez cuentistas ecuatorianos and Contemporary Ecuadorian Short Stories. Her own works include Es un monstruo grande y pisa fuerte: la minería en el Ecuador y el mundo and A History of Ecuador/Una historia del Ecuador. Fieweger lives in Ecuador.

More Interviews