Myopic, Fanatical, Absurd | A Conversation with Mark Haber

Interviews

By Odie Lindsey

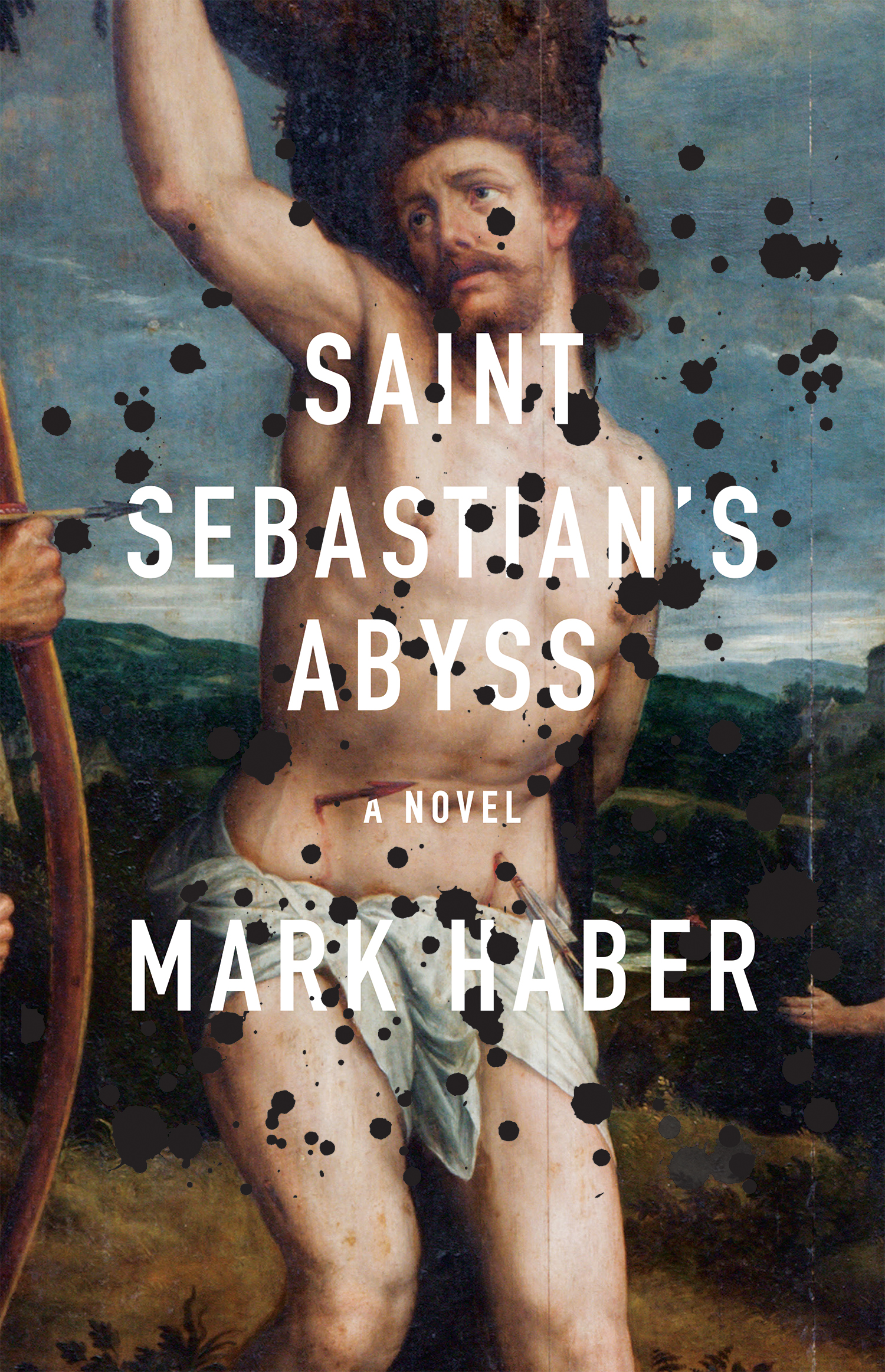

The rift between the two obsessive scholar-critics of Saint Sebastian’s Abyss is a thing of stylized joy. Author Mark Haber (Deathbed Conversions, Reinhardt’s Garden) has written a cerebral, comic novel about art critics in full colonial-academic mode, desperate to plant their flag on a patch of cultural dirt, define it, and fend off any forces to the contrary—including, as it turns out, each other.

The novel begins at the end, when our narrator, an American, is summoned to the deathbed of his art school bestie turned bitter rival (and apex Austrian), Schmidt. En route, we learn that they have devoted their lives, and their many, many books of criticism, to a single painting by Count Hugo Beckenbauer: “Saint Sebastian’s Abyss.” Our protagonists have consumed it. Communed over it. Spent years, side-by-side, taking in every tint, stroke, and image. (The novel presents a biography of the fictional Beckenbauer himself, including his descent into sexed-up, syphilitic degeneracy and/or divine, post-lapsarian vision.) Their rabidity has in turn broken their friendship. There are public condemnations. Personal insults. A mustachioed art gang who pledge loyalty to Schmidt.

Will this last-gasp journey provide a reckoning? Time tells.

It’s funny, this book, from line-to-line. Yet it isn’t a one-liner. Shattered friendships and deathbeds still do what they do. Beyond plot, however, Saint Sebastian’s Abyss is about voice. Sustained tone. This is smart telling, a meditation on highbrow culture and criticism, and the bumbling, selfish ruin that can define it.

During our conversation, Mark Haber was good enough to answer a few questions about his novel, art critics, stylists in fiction, and his work at Houston’s outstanding Brazos Bookstore.

Odie Lindsey: Following the traditionalist principle that a critic’s first step is to “describe” the work being examined, can you give a brief, art critic’s overview of Saint Sebastian’s Abyss?

Mark Haber: Not being an art critic, only someone who writes about them, I’ll do my best. Saint Sebastian’s Abyss is a slight novel with big ideas. It’s a meditation on friendship, obsession, madness, and how art speaks to us. It centers on two celebrated art critics and their infatuation with a single work of Renaissance art. Having fallen out years before, one is called to the other’s deathbed in the hopes of a reconciliation.

OL: While Saint Sebastian’s Abyss is a novel about obsession, it thrives on sustain. As in, you sustain the tone, the satire, the storylines, the wit and joy throughout. It’s a highwire act of style. When first thinking about the narrative, did you also imagine this telling?

MH: To me, both are intertwined. To me, the story is as important as the telling and vice versa. I love great stylists—Nabokov, Bernhard, Morrison, Marquez— and the style has always been the equivalent of the story for me. Imagine any great novel and the way it’s told is woven into the fabric of the story itself. I can’t imagine Beloved being written any other way because that’s as much of the novel’s power as what Morrison is telling the reader. So I didn’t think about tone specifically, even though tone is a constant concern, only because it’s always hovering. Ultimately, the story I’m telling and the way I tell it arrive simultaneously, if that makes sense.

OL: Are you a fine arts person? (You live in a fine arts town, yes?) How much authority, scholarly or otherwise, did you bring to this novel? What was the balance of real-world criticism/theory/history and fiction?

MH: I’m probably the opposite of a fine arts person! Houston is a fantastic city for the arts though. I live less than a mile from the Rothko Chapel and there’s an entire museum district here. But I’m a storyteller; my “fine arts” are books and literature. I did some research into Renaissance art and borrowed my wife’s books from art school to find terms and artists and aspects of art history I didn’t know. Other than that it was my imagination and love of language.

However, I do think the painting in the novel is symbolic of anything that inspires or creates an obsession.

OL: Please confirm that somewhere, someplace, you have a mock painting of “Saint Sebastian’s Abyss.” Perhaps, even, a triptych of mock paintings? Pray god, is there a Holy Donkey, lifted from the canvas itself?

MH: Everyone loves the Holy Donkey, including me! Sorry to disappoint, but there’s no “Saint Sebastian’s Abyss,” no triptych, and no holy donkey. Some modern art, but that’s about it.

OL: As a bookseller, you are inundated with titles, and with the commercial mission of sustaining a store. Are there bouts of antagonism between thoughtful reading, selling, and writing? Does it all flow together?

MH: That’s a fantastic question. There is an antagonism, but not with the commercial aspect as much as other aspects of working retail. At the end of the day, working at a bookstore is a retail job and the challenges, at least for me, are: A) finding the time to write; B) not being exhausted by books in general after work or when I have a day off.

The commercial aspect doesn’t bother me because there are all sorts of books and tastes and I appreciate that the books I like and I’m passionate about aren’t for everyone. I’ve always been able to separate what I want to read in my free time from what a customer might be interested in.

I do think it takes a deep love of the written word to want to try and tell your own stories after being around books all day and talking about books. I mean, you really have to love words, right? And I do get burnt out or tired sometimes, but then that hunger, that desire to write, something that began when I was probably seventeen or eighteen, returns. I’m lucky or cursed, but that hunger always comes back.

I should also point out that so much of working at a bookstore is non-literary, probably 75 percent. It’s organization, emailing with authors, publicists, agents, making sure the calendar is correct and up-to-date. Working on graphics, social media, vacuuming the store, fixing the printer, taking out the garbage, making sure the customers are happy, answering the phone, finding out why an online order was delayed, why did so many books arrive damaged, managing books on consignment. All of this and a lot more. Much of it is the same daily grind you’d be doing at any particular store. Believe me, I’m only a small part, really. We have a great staff.

OL: Saint Sebastian’s Abyss reminded me of other smart and fun and obsessive works like David Markson’s final books, especially This Is Not A Novel. (Okay, I read that book twenty years ago. Don’t judge if my gut memory betrays.) Are there authors, texts, and/or stylists who influenced you while you were writing your novel?

MH: I love David Markson! Yes, there are a lot of influences. Lar Iyer’s trilogy, Spurious. It’s funny and fantastic and a great display of highly intelligent scholars being ridiculous. David Antrim’s fiction is always there in my mind, as are William Gass, Vladimir Nabokov, Saul Bellow, Arianna Harwicz, César Aira, Jon Fosse. Certainly the voice-driven work of Thomas Bernhard, although my stories tend to leap off from a Bernhardian tone of myopic obsessiveness into the absurd. I don’t mind sprinkling in a little silliness if it fits, and I can’t see silliness ever suiting a Bernhard novel. Funny? Yes. But not silly.

But I love a huge assortment of authors and styles; even inadvertently they emerge in the work. You don’t see Toni Morrison or Fernanda Melchor, Krasznahorkai, Garcia Marquez and Céline, but they’re in there somewhere.

It’s also very arbitrary; the books I’m reading while writing might give me a great word or phrase or an insight into something I want to do. A lot of writing for me is arbitrary and that’s where the magic is.

OL: While the story thrives on wit, it also mines the cultural space, identity, and even value of the critic-as-villain. Do you like nasty critics? Are they, in fact, valuable to art and culture? Either way, how fun was it to inhabit two of them (with our narrator, an American, on the soft side)?

MH: It was a blast to inhabit them, Schmidt especially, who is wonderfully misanthropic and absurd. He’s very damaged, and I don’t know if we ever truly know what happened in his youth to create him, but there he is and we all probably know someone like him.

I love creating characters who are considered “authorities” on a subject and then making fools of them. There’s something I’ve always disliked about certainty, and people who are completely assured of their point of view or knowledge. It makes me suspicious, so I love to target that smugness. Probably because I feel like the older I get and the more I learn, the less I really know— and the more I’m willing to admit that. James M. Barrie said it best: “Life is a long lesson in humility.” If you become more assured by your point of view with age, I think it’s simply ego.

And, no: I don’t like nasty critics. I appreciate honest critics and honest criticism. Good criticism accesses a place of ideas, creates a conversation, that the author or artist often doesn’t see themselves. I feel like criticism is a very left-brain dialogue about a very right-brain activity. Criticism is being analytical about something that’s very often intuitive, instinctive, and creative. So I understand the argument that critics can take the fun out of something because they’re often very logical about something that’s mysterious and intuitive and thrives in the mystery. But it’s also a dialogue and a search for meaning which I admire.

OL: According to Schmidt, the European of the pair, “art died in 1906 with the death of Cézanne,” and anyone who studies it after this date is a “pseudoscholar, immersed in the forensics of garbage.” Was this date and delineation a random choice, or does it speak to a specific, critical battle line?

MH: The date wasn’t chosen at random, but based solely on the fact it was the year Cézanne died. It’s a strict line Schmidt draws, and it allows him to only consider dead artists, to be in conversation only with dead artists and dead movements. It’s his way of controlling the conversation. You can’t get pushback from an artist who’s been dead for centuries, right? I also think it’s symbolic of Schmidt’s uncompromising personality. “Nothing, nothing artistic has been created since 1906.” You know, it lends itself to humor and absurdity.

I also enjoyed ridiculing America—through Schmidt—by lambasting the taste and culture and relative youth of the United States. Some of what he says is very true, but I won’t say what.

OL: Regarding Ayne Bru’s “Martyrdom of Saint Cucuphus” (1504–07), a painting in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya’s permanent collection, a few questions. What’s up with that second knife, the one in the basket? Who’s the distant figure in the monastery doorway? Am I imagining things, or do St. Cucuphus’ bikini underpants feature a drawstring?

MH: Haha! I had never seen that painting before. That indeed is a drawstring. What’s more concerning is the calm conversation about the price of beets and potatoes happening two feet from the “Martyrdom” itself.

Odie Lindsey is the author the novel Some Go Home and the story collection We Come to Our Senses, both from W.W. Norton. He has received an NEA fellowship for combat veterans, the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Prize in Fiction, and the Dobie Paisano Fellowship. His website is oalindsey.com.

More Interviews