Telling People About the Lights | A Conversation with Matthew Vollmer

Interviews

By Nathan Dragon

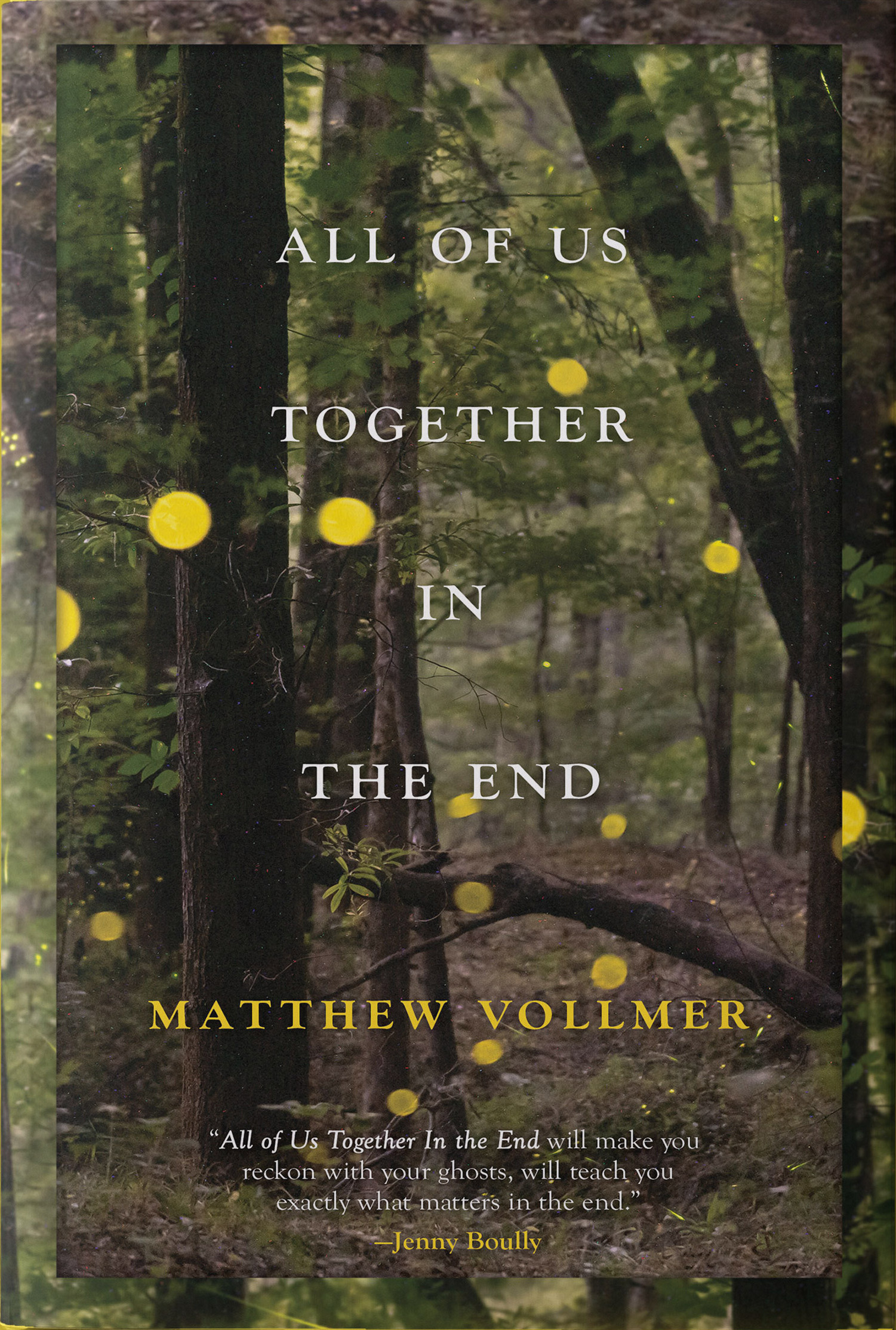

Matthew Vollmer’s All Of Us Together in the End was published April 4th by Hub CIty Press. I met with Matthew at his house two days after his book launch to talk. We sat in front of his garage in his driveway. It was roughly the same spot where I met Matthew for the first time in 2020. During that first meeting, he told me about these mysterious lights that his dad, he, and other people had seen out on his dad’s property in southwestern North Carolina. He told everyone this story at the time. He even tried to tell me about the lights the next time I saw him, like he hadn’t told me about them before. The appearance of the mysterious lights out in the woods started happening—or they were first observed by Vollmer’s dad—not long after Vollmer’s mother passed away after a decade of living with dementia. Vollmer and his dad didn’t quite know what the lights could be, but they had different ideas of what the lights weren’t. Vollmer’s parents are Seventh-day Adventists (SDAs) and, at one point, Vollmer was too. SDAs don’t believe in ghosts. His dad didn’t think it could be his mom but Vollmer, as an adult, may have been more open to that possibility, given the timing of the lights’ appearance and his mother’s death. Maybe it was a nice thing, like how some people associate the appearance of a cardinal with a loved one who died. I like that, but I don’t know if that’s necessarily a ghost-type thing, either.

When Vollmer was telling me about those lights that first time, I didn’t know what to think. I don’t know what to think about ghosts or paranormal-ish things. I lean toward not really believing in ghosts. This may be a product of having grown up working in a pizza shop in Salem, Massachusetts. People swear there’s plenty of haunting in Salem. Tourists flood to and through every October for what’s known as “Haunted Happenings” and Salem Witch Trial history. I’d be working counter at the pizza place, getting asked about ghosts and whatever else. I got a little burnt-out on the haunted hype. I never experienced anything.

But, after a while, I didn’t hear Matthew talk about the lights much. I figure maybe it was because he was writing this book and wanted to keep it close. I was happy to finally read All Of Us Together in the End, and I hoped to learn about any new developments. It’s a beautiful book about family, growing up, and the SDA church. It’s organized like a Charles Bowden book. The sections or chapters reiterate and repeat certain things, in a palimpsest-like manner, and the subject matter, though it all connects, jumps around. There’s an investigative thread. I told Matthew I thought the way the book is organized is endearingly sloppy. What I meant was: it’s got its own system. But maybe I’d put it differently now, a few days later, writing this, thinking about that.

Nathan Dragon: Can we start by talking about music? I know it’s important to you now and was growing up. And this is a musical book in many ways.

Matthew Vollmer: It’s true. Music was a huge thing for me growing up, especially in boarding school. Whatever was behind it, even if you were questioning it, the right song could put you in the oh I feel this. The presence of God is here. Because you’re all singing earnestly, and it’s a beautiful melody. But we also had this skit that we inherited from a conference that we went to every year. And certain people went and when they came back, they were just changed. They were like, “Oh my God, it was the most amazing thing.” You go for a weekend. You sing songs, have breakout groups. It was all about not doing drugs, but no one who went was doing drugs. But they were like, “We’re gonna not do drugs!” They had this wordless skit they would put on, but it was done to Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart.” In the beginning, you know how there’s the slow piano? And the skit’s a mother and father wondering where their son is. Or they’re in distress, and they’re kind of arguing. Their son comes in, and the father and son have a fight, and the son goes away to this other part of the stage, where all these people are wearing black and holding these placards with drug names on them. Like weed, PCP, even snuff. They circle around him and put the placards on him. Then the father, during the big emotional climax of the song, he’s trying to push through the chain of people. He can’t do it until they both fall on their knees to pray. Then the chain breaks. It was ridiculous, but we thought it was so moving because of the music. “Total Eclipse of the Heart “ is a huge melodramatic . . .

ND: Banger.

MV: Totally.

ND: So when you were doing or seeing this skit, you were at boarding school? You grew up in North Carolina . . .

MV: I grew up in North Carolina, but in the very, very Southwest corner of the state. And my boarding school was two hours away, in north Georgia. Our church was split up into conferences almost like the US is split up into states. They would have the southern conference. It would include that little tip of North Carolina, so that’s the school that was a feeder for the conference.

ND: Sort of how Catholic schools and stuff like that belong to dioceses.

MV: Exactly.

ND: So the other thing I want to ask, because you talk about it in your book—and I’ll say the name, to make sure I’ve at least said it, All of Us Together in the End—you talk about how fun it was to hide and have musical contraband. Like hidden Metallica tapes.

MV: Whatever. Yeah. The Cure, New Order, Smiths.

ND: Was there something in that music you all bonded over, or that moved you all, like seeing those musical skits anchored in the church? Or was it kids just being kids?

MV: We liked music in all of its permutations. When you’re a kid, especially when you’re a teenager totally deprived of so many cultural norms—TV, radio, you name it, meat, jewelry, Dungeons & Dragons, so many things that normal kids had access without thinking about it that were just off-limits for us—to sing or play guitar, whether it was “sacred” or “worldly,” had a huge effect on us. I’ve actually been thinking a lot about deprivation. We have access now to whatever we want. Whatever song we want, right there in our pockets. Back then, you would turn on MTV and it would be Madonna, Michael Jackson, Prince, whatever. It wasn’t until you got to 120 Minutes, a 2-hours show that came on once a week, that you could see and hear the Pixies and The Cure and REM, the non-top 40 shit. You would watch that and wait for your favorite band to come on. And they may show The Cure, and they may not. But when they did it was like, “Oh my God I saw the ‘Just Like Heaven’ video!” Same thing when you went into a record store. Were they going to have X, Y, Z? Were they going to have those import CDs? Like The Cure’s “Live in Paris” or Belgium or whatever. I don’t know who they were produced or put out by. You were always looking for stuff that you couldn’t find. It wasn’t always readily accessible, which made life suspenseful and dramatic.

ND: Is there a bigger mystery to the world maybe? When you’re deprived of culture, that is?

MV: I think so. For the four years we were at boarding school, we didn’t know what was going on in the world, and we didn’t care. We didn’t have TV. There were newspapers in the library we might’ve looked at for sports, entertainment, to find out what movies were out, read our horoscopes. But we didn’t care what was going on in the world because the most important things to us were the things happening at our school. Like who was hooking up with who, or dating who, or who had broken up with who. Just the dramas that go with being teenagers locked in a building with a hundred other boys, with the girls on the other side of campus locked in their building—which we couldn’t go into. But every week you could sign up for town trip. You’d get in a van and ride to the local Walmart where there was a Taco Bell. People would come back from town trip flexing because they had a whole pizza or something. Or they would sell burritos back on campus. Buy ten and sell them.

ND: I like this context. These are all the formative things and . . .

MV: Let me say something else. Again, I’ve been thinking about deprivation. Raising my son, I did the total opposite. I gave him whatever he wanted and we joked, walking around the city where his college is, and I was saying, “The memoir you’d write is about being deprived of deprivation.” But, for me, the Sabbath was also always a weekly deprivation. Friday night, as soon as the sun goes down—even before—you turn off everything. TV, radio, secular anything. That’s for 24 hours. There’s something about the Sabbath that’s really compelling to me still. I kind of wish I could still do it: turn everything off for 24 hours, and look forward to that 24-hour period. Because, at the end of that 24-hour period, you’re like, “Let’s get back to it. Let’s plug back in.” But being deprived, it’s a different state of mind. I’m not going to watch TV, read whatever it is. The deprivation just activates a contemplative spirit.

ND: Yeah, big time. I feel like it would be a useful practice for most of the world—or a lot of people at least—today.

MV: Oh yeah, totally, because we’ve always got the next thing to swipe or click.

ND: I thought one of more the fun-to-read scenes in All of Us Together in the End was your baptism. At the river?

MV: At the creek on our property. I was eleven. For whatever reason, that was always the age when people got baptized. I thought that doing it in a river or creek was more legitimate because that’s where Jesus was baptized.

ND: I guess this deviates from the ritual question, but is there a thing with SDAs and numbers, too? Eleven seems specific. And I guess I don’t really have knowledge about these things, but I’ve heard from some people that 222 is an angel number.

MV: Right. Numbers are really important. Like the seventh day. And there’s a really great sociological study on Seventh-day Adventism called Seeking a Sanctuary. It’s by these two British authors, Bull and Lockhart. I discovered it not long after I graduated college. Somebody recommended it to me. Reading it was mind-blowing. Adventists are basically invisible in the larger culture. People get them mixed up with Jehovah’s Witnesses, Mormons, whatever. It’s because they’re very insular. If you’re not in the know, you don’t know. But these guys did an objective sociological study on Adventist behaviors, and it was so fascinating because, for instance, they’re very focused on time. You need to know what day it is, what time it is. You need to know when sunset is on Friday. They frown upon adornment and jewelry because it calls attention to the physical self. So instead of giving engagement rings, Adventists give each other watches.

ND: Oh, that’s cool.

MV: Of course they would—because they need to know what time it is.

ND: There’s a utilitarian purpose to watches. Do they do wedding rings or bands?

MV: Many people do. My mom always wore a wedding ring. My dad didn’t until recently, when he got remarried. I seem to remember him saying something about how, because he’s a dentist, having a ring was an obstruction or something. But wedding rings aren’t frowned upon. Jewelry, makeup are. Most Adventists I knew growing up wore plain dresses. Growing up, I felt like I could spot an Adventist in a crowd.

ND: Okay, so two-part question. Part one: “decisiveness.” You write in your book that when you moved to Massachusetts and you had a Saturday to yourself, that was the first time nobody was going to check whether or not you went to church. And you didn’t go. That was obviously decisive. But I could also picture a Vollmer sitting there, thinking about how church is in fifteen minutes, ten, and then now he can’t make it anymore. Is that accurate? Part two: it seems like you have to be decisive as an artist. You’re a great artist; your writing is phenomenal. Do you think of that as being something that comes from making concrete decisions?

MV: For part one: it’s hard to remember the specifics. But I definitely don’t think it was like, “Am I going to go? Am I going to go? Okay, now it’s too late to go.” I think I was secretly relishing the fact that no one was going to check up on me. “I can just not go. Let’s see what happens.” Then I saw the artifice of church. I never stopped believing in God. The content of God has changed for me. I might say that, right now, we’re experiencing the divine by having a conversation about what it means to be human and whatever. I don’t believe in a physical grandfather . . .

ND: With a shepherd’s staff.

MV: Right. Who will smudge me out with his thumb at some point. It took me a long time to get rid of the Sabbath. If I didn’t go to church, I was definitely not going to work. I wasn’t going to do school work. I might go to the theater or watch TV. But I wasn’t going to work. That was so ingrained in me for years. And I wonder if keeping the Sabbath and all the other rules I grew up with has something to do with my preoccupation with artistic limitations. I wonder if there’s a relationship between having grown up with all these rules and restrictions and becoming a writer who messes with literary conventions. You tend to have this mentality of, “What can I get away with?” Like you can’t play sports on Saturday. What if we played Bible basketball? Where you had to quote a Bible verse before you shoot the basketball. Does that count?

ND: So, instead of playing HORSE, you could play JESUS?

MV: Yeah, something like that.

ND: That’s cool.

MV: That’s the kind of shit we were always trying to do. How do we get around not being able to do fun stuff on Sabbath. I think there’s also joy and delight in transgressing, in breaking the rules. It makes me think of Uncle Arthur’s Bible Stories, these anthologies by this British guy [Arthur S. Maxwell] about kids who disobeyed. They were supposed to be true stories but they seemed, sometimes, like fiction. They were stories about kids who would break the rules, and there would be consequences, and suddenly the kids would understand and be transformed. The endings of the stories were always like, “And so and so never disobeyed mommy and daddy ever again.” What world were these people living in where you do one wrong thing, there’s a consequence, and they never do anything wrong ever again?

ND: Makes me think, “No mom and dad never caught so-and-so again.”

MV: I never thought of it that way. But, yeah, I see my fixation on rule-breaking as an artist—or setting up rules, like “I’m going to write X amount of essays in the form of an epigraph but it has to be one sentence long,” just setting up these arbitrary rules for myself—creates a situation in which I can be more creative. I’m building a container that I need to bust out of. Like David Hockney saying, “If you were asked to draw a rose with 500 lines or five you’d be more inventive with five than 500.”

ND: Did you have a set of limitations for All of Us Together in the End? Or was writing it a little bit more free?

MV: More free. I had been working on a book about growing up Adventist in the years preceding my mom’s death. I turned that book into my agent two days before my mom died. I also sent it to Evan Lavender-Smith around that time. He got back to me and said, “You know, I just think you’ve got more revision to do.” And as he was talking me through it, I was thinking, “Oh, man, I think you’re right.” Then I talked to my agent. He had reservations too. I remember he said something like, “I just don’t know how many people want to read about another person’s personal grief.” My response to him was, “Have you ever read literature?” He must have had some angle I wasn’t quite getting. Even if you’re expecting your parent to die, which I was for ten years, you won’t know what that feels like until they’re actually dead—until you go and see their dead body and you touch their skin. You lift them out of their bed and into their coffin, shut the thing, and see it put in the ground.

ND: The first time I ever met you we were right here. Me, you, Evan and someone else. I was thinking about how interesting and bizarre it was, and also moving, now that three-ish years have passed since you saw and heard about the mysterious lights and started telling people about them. You’ve done all this research that’s both spiritual and scientific. There was the guy from South Dakota who studied . . .

MV: The funny thing is, he studied it and documented it, and his conclusion was that he couldn’t figure it out. We just don’t know.

ND: Is that the best-case scenario: that we don’t know?

MV: To me, personally, it is. I want to not know. If I know, that closes the door. You know what I mean? Case closed. That was an alien or a ghost. To me, the lights are symbolic of something that’s really important and that a lot of modern-day people are uncomfortable with. And that is the unknown.

When I was laying in my mom and dad’s bed, where my mom died, and looking out the open window at that blinking light in the distance that only I could see from that open window—I think back to that, and I think that’s a signal reminding me that saying I don’t know is really important. And that mystery existing at the heart of human experience is just as important if not more important than saying you know for sure. Because if you know something for sure, or if you have the answers to everything in life, you build up this fortress against everything that’s possible. You’ve created limitations, and it comes back to those limitations, right?

ND: I was thinking “decisiveness” the whole time you were saying that. Not knowing and being cool with it is way more decisive than being falsely arrogant, thinking you know everything.

MV: But it’s also just the way you go about the world. Are you going to be listening to someone else narrate an experience, thinking in the back of your mind, Oh, they’re wrong? Or are you going to be open to what they want to say and willing to learn from it?

ND: I got three-quarters of the way through your book and I started thinking about the structure and organization. I think one of the things that surprised me the most was how you put it all together. It reminded me of Charles Bowden. Maybe you see this differently. I don’t mean to offend you, but there’s an endearing sloppiness to the organization.

MV: For sure. When I first started writing the version of this book before my mom died, I did it during a teaching sabbatical. I thought I’d just write whatever came to mind. A quasi-mediative, associative, chain-linking narrative that was amorphous. There was a shape in that things were connected, but it was actually the occasion of investigating the lights that gave it a shape and a structure. That was interrupted by COVID, which was interrupted by my dad reconnecting with his old flame. So there were these structures that were in place, and then there were these disruptions that made sense and created tension. It allowed me in, the beginning—even when I read it now, I think to myself, You introduce the lights and then you talk about family, you talk about church, and it takes a while to get back. I can’t believe I got away with that. Because when you get back to the lights, the reader will remember that that’s what this is about.

Nathan Dragon’s work can be read in NOON Annual, The Baffler, New York Tyrant, and more. Nathan edits and co-runs a small publication project called Blue Arrangements.

More Interviews