Finding Poetry in the News | An Interview with Ashton Politanoff

Interviews

By Ryan Ridge

In his late-career poem “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower,” the wise doctor, William Carlos Williams, offers a memorably grim prognosis regarding media consumption.

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

Translation: the primordial power of poetry possesses the ability to save us. Yet the more seductive scourge of the news cycle distracts us and destroys us. Indeed, you won’t glean the news from poems. But what about the other way around? Is it possible, with the right kind of eye, to find poetry in the news?

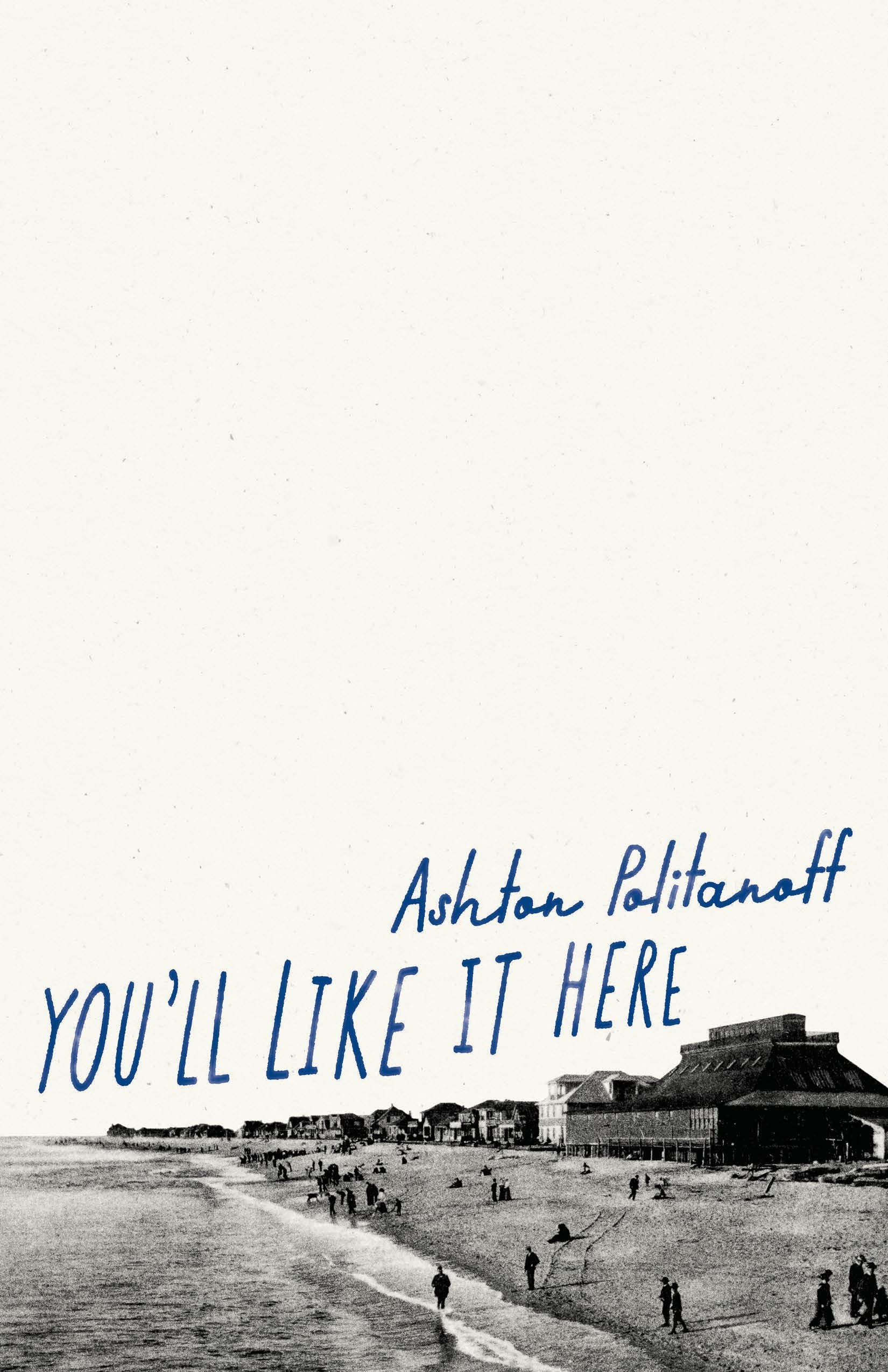

Enter Ashton Politanoff’s fiercely original new book about old news, You’ll Like It Here. In YLIH, Politanoff combines a poet’s sensibility with a curator’s eye to renew and write through the jettisoned headlines of a California beach town in its infancy. The project is an excavation and exploration of a specific time and place (Redondo Beach, California, in the early twentieth century) as well as a metaphorical mirror to our new now. An instant classic, You’ll Like It Here belongs on the shelf next to other news-inspired masterpieces like Félix Fénéon’s Novels in Three Lines, Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, and Corwin Ericson’s Checked Out OK. If you’re anything like this reader, you’ll love You’ll Like It Here.

Via email, Ashton and I chatted about place, process, loss, and inspiration, among other topics. Our conversation occurred in early September as a record-setting heatwave engulfed most of the West.

Ryan Ridge: Could you talk a bit about how this wonderful and wonderous book, You’ll Like It Here, came to be? What was the initial spark, and when did you know you had a project on your hands?

Ashton Politanoff: I wanted to write about the South Bay (comprised of Redondo, Torrance, Manhattan, Hermosa, El Segundo, and Palos Verdes to name a few) for some time. Initially, I was trying to write about the surf community, researching the 50s and 60s. I poked around the local newspaper archives, but I found a quaintness in the early twentieth century. It was filled with objects of wonder and charming little stories with a maritime backdrop that I couldn’t turn away from. So it began.

RR: Do you remember the first piece—the big bang inspiration, as it were?

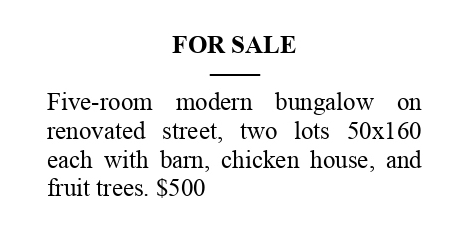

AP: The first piece I found was one advertising the sale of a five-room beach bungalow for $500. I couldn’t believe the price!

RR: Ha! Yes, I’ll take ten of those bungalows, please! Those were different times. Along the same lines, I would think that if you had worked on YLIH at a different time in your own life, one not overshadowed by the loss of your mother, it would have emerged as a different book. How did your emotional or psychological state/feelings shape your writing process? Do you think you would’ve made the same choices around craft if you were exploring a place and not tethering it to your mother? (Kudos, by the way. When my father died, I went on a heroic bender and didn’t write anything for almost a year, but you managed to process your loss and channel it into something creative.)

AP: After my mother’s passing, I had an obsession with the past: old single-fin longboards, classic cars, the photos of Leroy Grannis, the Palos Verdes Surf Club, Doc Ball, original South Bay homes. I spent $200 on Ebay on a copy of a book— Castles On the Sand—dedicated to old beach bungalows in Hermosa compiled by a local librarian.

Curation was also part of this project. I imagine that even if I had undertaken this project at an earlier time, I would have made different choices.

RR: How did you decide what to curate and what to write through? Did any of the pieces you came across feel readymade?

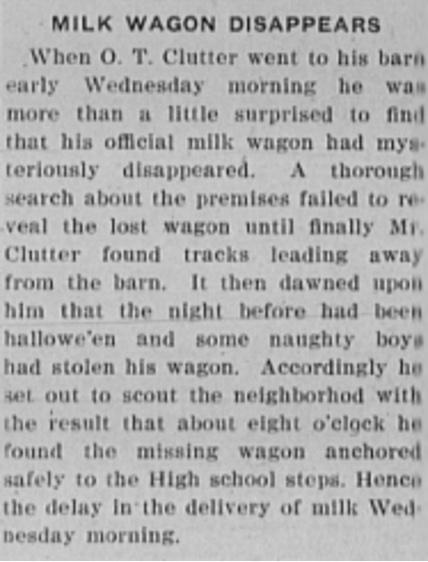

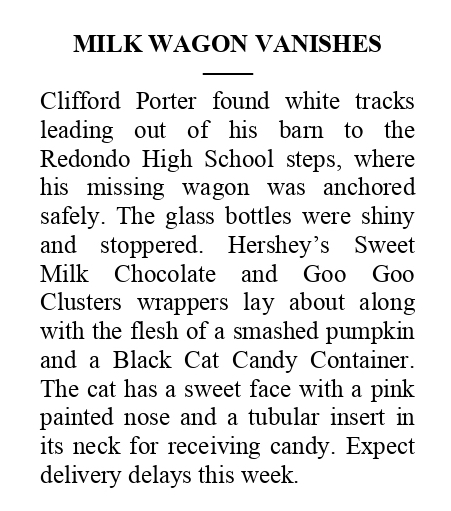

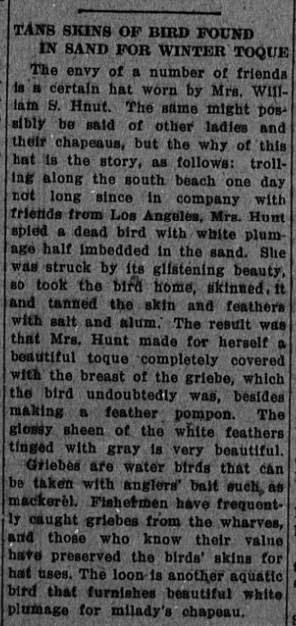

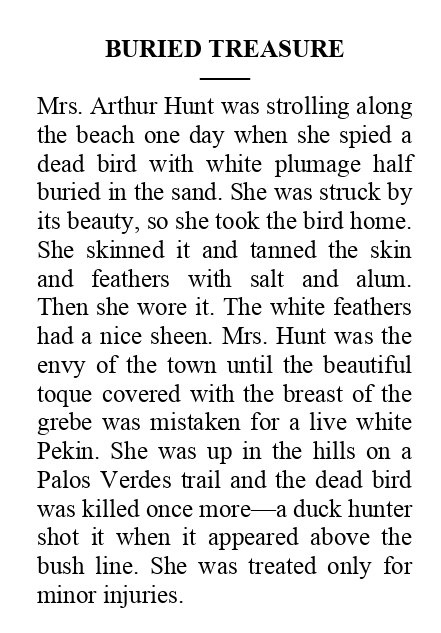

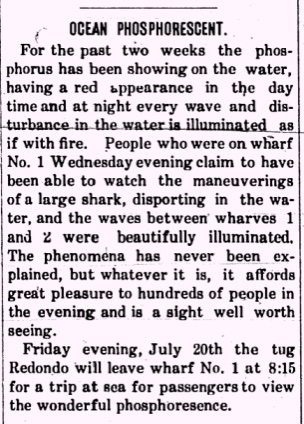

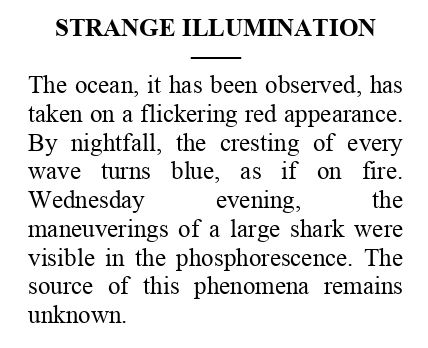

AP: All the pieces have been tinkered with to some degree. Some have been extended and others reduced. I often removed what I viewed as extraneous to the narrative I was trying to distill. I’ve included a sample of screenshots of originals alongside my modifications.

RR: I want to ask you a bonehead question. Genre? What is this?

AP: I’ve already seen the book labeled as both a short story and poetry collection. I intend for it to be read like a novel. The book is hard to define, and I didn’t know what I had even when I was working on it. That was a part of the excitement.

RR: I’d love to hear about your assemblage process. In a bricolage like this, it feels like you’re making decisions about how pieces juxtapose against each other, reverberate, or create new ways of seeing. What were you thinking about as you were ordering the book? How was sequencing a part of the curatorial process? And can you say a little bit about titles, as each title adds another tier of complexity to the pieces?

AP: In the initial draft, I thought about escalation. The boys at the end of Part I find a buried gun. By Part III, we are seeing a world that mirrors our own: a small town that is no longer untouched by war, disease, internal strife, discontent. I wanted the whole thing to feel mythic.

In subsequent drafts, I tried to tease out more of the subtler themes. I added a first-person voice. Photographs were included. Titles were often revised and obscured. Could the title zig and the story below zag? That was one approach I took.

RR: I’m interested in some passages that speak to the natural world and the environment. They’re striking because they’re from a different time but speak to today’s world. Do you think there are things for us to glean from this period regarding the natural world? Were you conscious of a particular thread or thesis related to environmental concerns?

AP: It was hard not to ignore these clippings, pining for an idyllic world where natural phenomena like the phosphorescent ocean during an algal bloom or grasshoppers raining from the sky occurred. I found comfort in these moments.

But at the same time, when I read about fires and massive storms, it felt portentous.

RR: Having engaged so closely with the news from another era, has that changed how you view our news today? Do you read it differently? Have certain things changed or remained the same?

AP: I consider this book a work of fiction despite what it’s based upon. However, due to the very nature of the project, the clippings themselves inevitably became darker as time went on. It’s difficult not to worry what we are building towards.

RR: I asked you about time, but could you say a bit about place? You’ve written a California book. Specifically, it’s about Redondo Beach a hundred years ago. But what’s the vibe like now? Do you like it there? I lived a couple of towns away in Long Beach for several years, and that place is full of characters. The West is still wild indeed.

AP: Redondo Beach and the surrounding beach cities have changed significantly. There are new developments, and one can spot the green construction fences of future teardowns all over the place. Fortunately, the Redondo Pier hasn’t changed much, and I hope it stays this way. In general, the cost of living in California is exorbitant. We have many friends that have moved away.

RR: Yes, I always say California is a great place to leave. Of the places I’ve left, it ranks highly. Yet I go back to it in my mind all of the time. It’s the biggest part of my creative imagination, an inspiration. Speaking of, what were you reading, watching, or listening to when you wrote YLIH? What other influences do you feel reverberate through this project?

AP: Leading up to the book, I was reading Édouard Louis’s Who Killed My Father, Kirsty Gunn’s Rain, Joan Didion’s Play it As it Lays, and Christine Schutt’s Prosperous Friends. I consider all of them masterpieces. I love the sheer impact of a shorter novel.

RR: From Anne Carson to David Markson, Ishmael Reed, Harry Matthews, etc., Dalkey Archive has released the greatest experimental literature on the planet. How was it working with this legendary press?

AP: Dalkey is a national and international treasure, and I feel honored to have a book with them. Diane Williams and Christine Schutt—two other writers with Dalkey books—are my heroes, so I am ecstatic that Dalkey is the home for You’ll Like it Here.

RR: What’s next for you project-wise?

AP: I have a short story collection that I’ve been working on for some time. I also have been taking pictures and making notes on something new.

Ryan Ridge is the author of eight books, including the story collection New Bad News (Sarabande Books, 2020) and the poetry chapbook Ox (Alternating Current, 2021). His work has appeared in Denver Quarterly, Moon City, Passages North, Post Road, Salt Hill, Santa Monica Review, Southwest Review, TRNSFR, and elsewhere. An associate professor at Weber State University, he codirects the Creative Writing Program. In addition to his work as a writer and teacher, Ridge plays bass in the Snarlin’ Yarns. He is working on a novel.

More Interviews