Muscles & Imagination | An Interview with Tyler Keith

Interviews

By Max Hipp

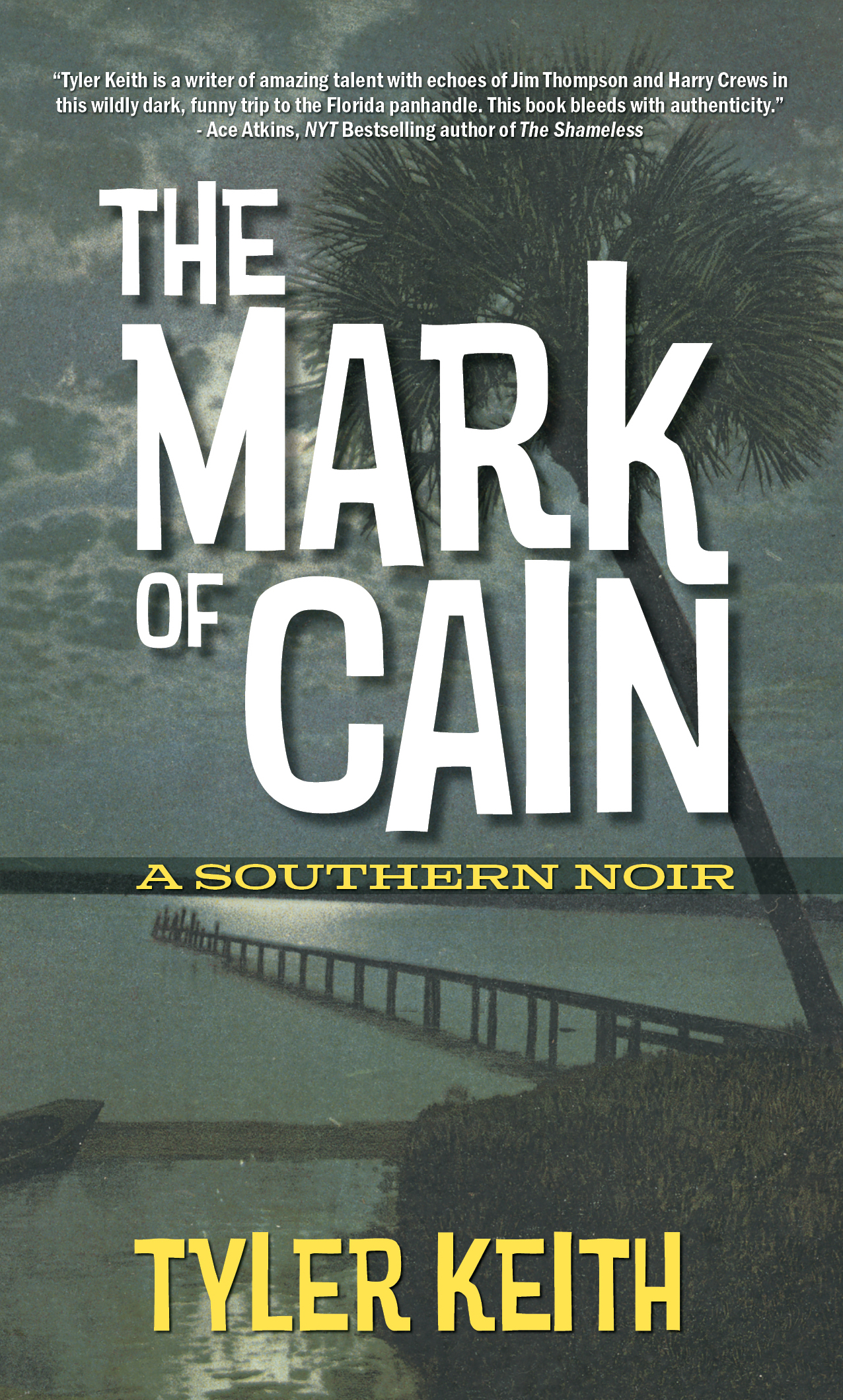

Tyler Keith is a songwriter and guitar player (Neckbones, The Preacher’s Kids, The Apostles, Teardrop City) who’s made over a dozen albums over the past thirty years. His solo record, The Last Drag, and his latest album with The Apostles, Hell to Pay, are both available from Black & Wyatt Records. In addition to all the music, he’s recently published his first novel, The Mark of Cain, available from Cool Dog Sound.

The Mark of Cain opens like a classic noir/crime story: a man gets out of prison. This time, however, our narrator is Ronnie Harrison, a tough-but-decent ex-con just trying to walk the straight path. He arrives at Camp Eden, a halfway house with a Pentecostal slant, where he must do as he’s told and stay out of trouble or else return to the penitentiary to serve the rest of his sentence. He scrounges through the shards of his life, reconnecting with his ex-wife and the daughter he hasn’t spoken to in years. He has to reckon with his past and deal with the rest of the Harrison clan, whose business has changed with the times from moonshine to marijuana to meth.

Keith describes the denizens of Ronnie Harrison’s world with agitated lines full of punchy imagery. For example: “They seemed to have bitterness and a dangerous anger that showed in their faces, like the markings on a poisonous snake you know you should steer clear of.” Or: “I could smell the penitentiary on him, the bleach and misery.” This sentence-level drumbeat of menace recalls crime/noir greats like Jim Thompson and fellow Floridian Charles Williford. Keith evokes the highway bars, motels, and strip clubs of the 1980s panhandle in authentic stucco and neon. By the time the novel hits top gear, Harrison’s past and the nightmarish underworld of Holmes County, Florida, come roaring into view like a dragster.

He’s been on the road a lot this year, so our interview was conducted over email in February.

Max Hipp: I’ve been thinking about creativity, wondering if it comes from within us, outside of us, or some combination. You’ve been creating for a long time. When did you first start making things? Did you make anything when you were a kid or did it come later?

Tyler Keith: I think it started as an extension of my imagination. I spent a lot of time alone or with my best friend, Mark, making up stories or storylines and playing. Like police dramas or S.W.A.T. detective. I wrote a few stories in high school just for my own amusement. The school I went to my whole life, from K-4 through twelfth grade, was very strictly Christian and did not encourage individuality or creativity at all. In fact, it was discouraged and punished. I think many creative people are stifled by school. It takes a person’s natural instinct to express themselves and crushes it. But, for me, by the time I reached my senior year, I had already decided that school was completely full of shit. I was getting out of there and never coming back, and I was going to try my hand at writing. I was completely in the dark about how to go about it, but I began compulsively writing around then. In notebooks. Lots of bad Beat poetry and some one-page William Burroughs fake stories. It was something from within. I hadn’t been able to get a band together at that time and really never considered songwriting, although my brother had written some good songs. I wasn’t comfortable singing in front of people then. I’m not saying I have any God-given talent for anything, but I feel like I’ve always had an urge to scribble and draw and make up stories. It’s just the way the DNA shook out in my brain.

Tyler Keith: I think it started as an extension of my imagination. I spent a lot of time alone or with my best friend, Mark, making up stories or storylines and playing. Like police dramas or S.W.A.T. detective. I wrote a few stories in high school just for my own amusement. The school I went to my whole life, from K-4 through twelfth grade, was very strictly Christian and did not encourage individuality or creativity at all. In fact, it was discouraged and punished. I think many creative people are stifled by school. It takes a person’s natural instinct to express themselves and crushes it. But, for me, by the time I reached my senior year, I had already decided that school was completely full of shit. I was getting out of there and never coming back, and I was going to try my hand at writing. I was completely in the dark about how to go about it, but I began compulsively writing around then. In notebooks. Lots of bad Beat poetry and some one-page William Burroughs fake stories. It was something from within. I hadn’t been able to get a band together at that time and really never considered songwriting, although my brother had written some good songs. I wasn’t comfortable singing in front of people then. I’m not saying I have any God-given talent for anything, but I feel like I’ve always had an urge to scribble and draw and make up stories. It’s just the way the DNA shook out in my brain.

MH: Place is important in this novel. Alan Moore likes to talk about the concept of psychogeography in his writing. No need to get into the finer points, but it’s basically the idea that the traumatic history of a place (wars, colonization, slavery, genocide) leaves a kind of psychic imprint on the individuals in and from that place. How might this idea connect with Ronnie Harrison or the other characters in 1980s Pensacola and Holmes County, Florida, as portrayed in The Mark of Cain?

TK: I think that Ronnie has the Holmes county psychogeography implanted in his mind. The history of the place is deep in there. He’s haunted by it. The whole family is. It’s a place of violence and dark mystery but also a place of beauty and certain treasured nostalgic memories. In a sense, it’s a place he has to return to. He has no choice in the end. Ronnie doesn’t want to look at the place too closely because it means looking at himself, but he must confront what’s happened to his family there. But there’s always a price to pay for that. In some ways, the novel deals with a place where people turn a blind eye to things they don’t want to deal with or admit to themselves. I think that’s a theme common to a lot of Western films and books. So, oddly enough, place is so important, but it could also be Anywhere, USA. If that makes any sense.

MH: There’s something to the objects, names, images, and places in your songs, and in The Mark of Cain, this sensibility marries rock ‘n’ roll to the influences of Modernism (like the Symbolists and Imagists). Is that coming through Bob Dylan and the Beats, maybe filtering into the art and punk rock of the seventies and eighties? Any Dylan/Rimbaud/William S. Burroughs in your recent music and/or writing?

TK: I’ve definitely been a fan of the French Symbolist poets since my late teens, and I was always a Dylan fan. I think the fact that I grew up in a religious environment that taught everything in the Bible was both symbolic and completely true had a big impact on my thinking about writing and music. Everything has a spirit. That’s what the Holy Spirit is! It’s everything. I think this really hit home for me when I discovered things like The Plague by Albert Camus. It made sense in a non-Christian way. The first stories I wrote in college were very abstract and full of symbols. The problem was that they were not very good. A lot of the meaning only existed in my head.

This was one lesson I learned from Barry Hannah. He pointed out this mistake. It made me realize that, in song or story, meaning should be something inherent. Also, you probably needed a beginning, middle and end, even though you don’t have to have a complete storyline. In rock ‘n’ roll, something like “Jumping Jack Flash” or “All Along the Watchtower” are conceptual story songs with an unclear storyline. These types of songs—and even other less abstract songs such as “In the Back of My Mind” by the Beach Boys—seem to match up with what Barry Hannah does in his stories. There’s a distinct voice there.

Another early influence for me was Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground. I didn’t see much difference between that and The Killer Inside Me by Jim Thompson. It almost seemed like the same voice. And A Season in Hell. I think I finally learned in writing songs that I could use the voice of a character or a narrator. In the early years, I thought everything had to be exactly from life—that it had to be my voice. That lesson, which I learned first in songwriting, became essential when I came back to fiction. It opened everything up for me. I didn’t have to write a memoir or a fictionalized version of my own life. I could make everything up and still have it mean something. That seems like something someone should know, but it took me a while to grasp it.

MH: Speaking of rock ‘n’ roll, Ronnie Harrison is always noting the song that’s playing, and he seems to have good taste. What other ways do you think rock ‘n’ roll shows through in The Mark of Cain? Does it connect with Southern Noir, which is a marketing angle for the novel? It also seems like the feel and pulse of rock ‘n’ roll is in there.

TK: Rock ‘n’ roll and classic country played a big part in this book. I wanted the narrative to have a certain rhythm, and I wanted readers to hear certain music in their heads while reading. Also, sections of the book take place in particular years, and I wanted it to be somewhat accurate. Ronnie is also a driver and somewhat of a loner, so I wanted him to be as aware of the music playing at certain times as he would be. I wrote to some classical music at times, but they were very dissonant things, specifically Bartok’s String Quartets. I played that when Ronnie was experiencing some of his mental anguish and suffering. It helped to set my head in that space. I’m not sure how it affected the writing, but it definitely set the mood for me.

MH: You’ve said when you took Barry Hannah’s workshop, he told you to choose either writing or music because you couldn’t do both. Since you’ve been doing both for a while now, do you find that one art deepens the other? Can you do only one at a time? What’s the connection between music and writing for you?

TK: I took that to mean you had to choose one because all art forms are about obsession. It’s sort of like the Biblical idea that you cannot serve two masters. I think Barry was warning me that you had to feed one and let the other wither and die. Otherwise, they both would be anemic, and neither would flourish. And he was right about that. I became obsessed with songwriting to the detriment of fiction. But I still kept the flame burning inside for it.

Some of the lessons I learned in fiction translated to songwriting and vice versa. Like I said, you have to have a beginning, middle, and end; economy of language matters; you need a hook of some kind. The process of writing songs is different in the obvious ways, of course. It’s a different medium, but it’s basically the same for me. I start with an idea or title, then make sure my first verse/paragraph is tight and brings people in. I would record a demo on a four-track recorder and work out the kinks and clean up the language from there. The final product is really not done until it’s recorded in the studio with all the collaboration that takes place in that environment.

The process is similar to writing a book—or a chapter of a book. When you have twelve songs, you have a record. When you have thirty chapters, you have a book. But Barry was also right that when I went back to fiction, songwriting took somewhat of a back seat. The good thing is that songwriting has become much more of a skill now, so it doesn’t take as much head space as it once did. When I’m writing fiction, I’m pretty much obsessing about that. When I’m done, even with the first draft, I’m able to let some music back in there. So he was right in that I don’t do both at the same time, but wrong in the fact that you can do both. In the end, for me, songwriting and writing use the same muscles and imagination. But each one just sort of repurposes a few things.

MH: It’s interesting what you say about not knowing you could just make things up and write from a perspective other than your own. Did that come from some idea about being authentic? Like Holden Caulfield’s problem with phony-ness? Or was it some belief in The Word as law and truth or something?

TK: I think it just came from being a fan of Bukowski and Kerouac. I guess I thought you had to live it and then write it. I’m not sure exactly. The problem was I couldn’t remember anything, and when I kept a journal, I couldn’t stand to read it later. I think another reason I wanted to play and write rock ‘n’ roll and be in bands had to do with being “on the road.” It was the easiest way to escape. I hitchhiked a little bit, but it was scary! My first experiences with long rock ‘n’ roll tours profoundly changed my life. I was living so many new experiences and really connecting with my inner self that I had plenty of material for songs, things that were real life. So it didn’t occur to me to invent anything until later. My first seven years of creativity in rock ‘n’ roll consisted of a lot of raw energy and immediate ideas and construction. I felt like I was either drinking or making up songs, simple concepts and music that made it easy to access the most sensitive and inflamed emotions. In a way, that’s related to Christian fundamentalism: substituting rock ‘n’ roll for Christ. “I Surrender All,” as the song says. That’s kind of a joke, but not really.

Max Hipp is a writer and musician from Mississippi. His fiction has appeared in many fine journals, and he has a short story collection forthcoming from Cool Dog Sound.

More Interviews