Too Loud for the Status Quo | A Conversation with Elizabeth Ellen

Interviews

By Troy James Weaver

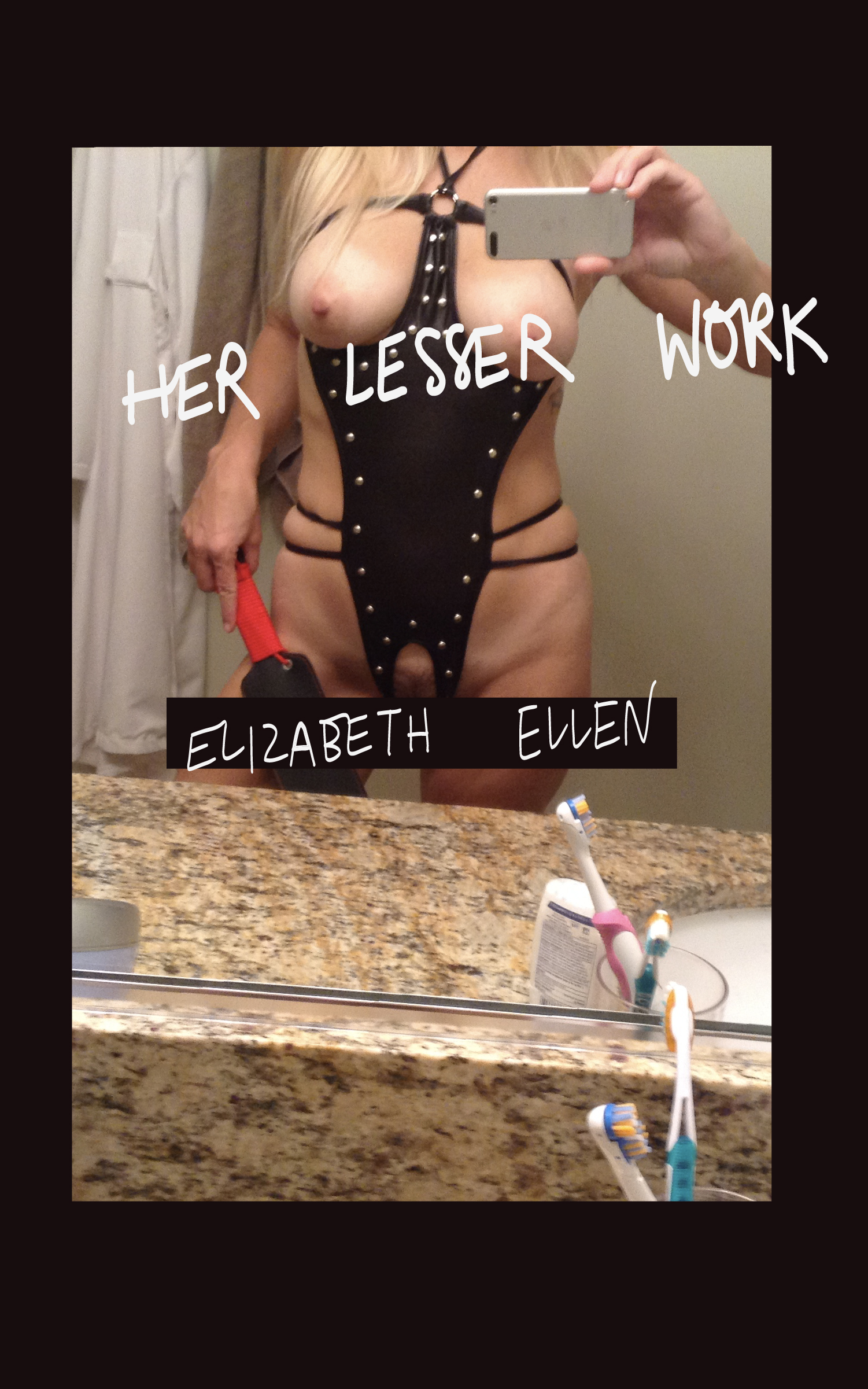

Elizabeth Ellen needs no introduction. But I will say this: I’m deeply humbled by her work, which I first encountered in American Short Fiction back around 2012. Ever since then, I’ve been a devout reader. She is fearless; a fighter, a champion, and a seeker of truths big and small, even when those truths are too loud for the status quo to handle. But the status quo has no choice. Elizabeth Ellen will firmly take her place as one of the greatest writers this country has ever seen. In my mind, she already has, and her new books, a collection of short stories, Her Lesser Work, and a play, Exit, Carefully, from Short Flight/Long Drive, cement my thinking. Elizabeth Ellen will undoubtedly stake her claim in the canon of twenty-first century American literature.

Troy James Weaver: Your story “Republicans” features a young woman coming home for Christmas break, but her family doesn’t live in town anymore. So she stays with the titular Republicans: her mom’s third husband, Waylon’s parents. But she doesn’t really stay with them, not quite. She spends most of her time with a friend at her friend’s boyfriend’s house, and she becomes the girlfriend of the boyfriend’s brother. They go to a monster truck rally; they do all the things you’d expect them to do. It is one of the most accurate portrayals of the Midwest that I’ve encountered. I can see a lot of people reading this and other stories in this collection and bringing up the whole question of autofiction. Is this real? Did this happen? How much of this is based on the author’s personal experience? That’s not my question. My question is this: do you think those kinds of questions are even important when it comes to fiction? In a way, isn’t everything fiction?

Elizabeth Ellen: I agree. The question is boring and irrelevant. Thank you for realizing this. When I read a story, while it may be human nature to wonder how much is drawn from the author’s life, it also doesn’t really matter. When reading a story, I only care if it’s interesting, either because I relate to it or because it makes me uncomfortable or because it’s doing something stylistically that interests me. That’s what I look for in fiction. I had a very close friend of mine text me after reading my Harper’s story and say, “So it’s nonfiction? I recognize a lot that’s in it.” I said, “It’s written in third person from a male protagonist’s point of view, how could it be nonfiction?” and I added a smiley face to the text so she would know I wasn’t trying to be a total dick. But honestly. How could I possibly know the point of view of the male protagonist or what he is actually thinking? It’s all guesswork. Or, as you might say: fiction.

TJW: The idea of celebrity pops up in many of these stories. One of them, “Snatch Shots,” has a celebrity as its main character. And celebrity references are sprinkled throughout Her Lesser Work. What’s your relationship to celebrity? What do you find appealing about using these references in your fiction?

EE: Oh, I guess that, like most people in today’s culture, I’m interested in celebrities because they are a usual focus of conversation. In this particular case, I was interested in a female celebrity’s view or experience with aging in the public arena. With what happens to her sex appeal over time—how she might deal with that, with public scrutiny and with her own idea of herself as reflected by society. And I think that’s interesting because most women go through the same thing as they age, just not in a national spotlight. But it’s still relatable. We share many of the same concerns.

TJW: In the story “(The) Conjuring,” something stood out to me that has nothing really to do with the story itself. A girlfriend and her boyfriend go to Home Depot to buy Dustbusters. The line I’m thinking of reads: ‘“I don’t get you, baby, why would you say shit like that?’ you say, your mask under your nose.” And the mask—that was a detail I didn’t expect. How many of these stories did you write during the pandemic? Or was this already a story that you later altered with that detail and I’m thinking about it too much?

EE: No, I wrote this during the pandemic. I think most were written prior but a couple after. It just felt natural to include that detail. Part of his character: Lol. He doesn’t give a fuck what people think of him at Home Depot, this dude. Yet he’s very concerned with what the female protagonist thinks (of him).

TJW: I’m curious about the title, Her Lesser Work. What made you decide on that title?

EE: Oh, I had that idea, for that title, for a while. Three years, maybe. I just always thought that was such an interesting, if shitty, phrase. Her lesser work. His lesser work. But also hilarious. Own it.

TJW: I think from the cover to the book title to the Hole lyrics that end the book, there is a larger statement taking place, like something much bigger than the great work contained within. Is this a way of saying “fuck you” to the haters?

EE: I’ll let the book speak for itself.

TJW: I love the way that “Person Under Train” is constructed. There is a lot of the quotidian in it, then things build to a most surprising, though mysterious, climax. Did you do one of those train residency-type things for writers? Or am I imagining that? Was that story written on a train?

EE: Train residency-type thing? What is that? I took a train from Ann Arbor to LA in . . . I don’t remember . . . 2018 maybe? And then rented a car and drove it back from LA to Ann Arbor. So I didn’t write the story on the train but the train trip certainly inspired the story, yes.

TJW: Yeah, as funny as that sounds, train residencies for writers were a thing. And for some reason I had it in my mind that that happened. Are you a self-taught writer? That’s kind of a stupid question. Aren’t we all?

EE: Sure, we all are, and I am. I don’t have an MFA, if that’s what you’re getting at. I never even had a mentor. I don’t know how this happened; observation, I think. Years and years ago. Observing writers and editors on The Atlantic’s Dave Eggers thread (in 2001/2002). Observation and practice. The 10k hours thing Malcolm Gladwell talks about.

TJW: Can you tell me ten classics that mean a lot to you, ten small press books that mean a lot to you, and ten writers in general who mean a lot to you?

EE:

Classics:

The Stranger (Camus)

The Price of Salt (Highsmith)

Strangers on a Train (Highsmith)

American Psycho (Ellis)

The Plague (Camus)

Play It As It Lays (Didion)

Post Office (Bukowski)

The Great Gatsby (F. Scott)

Nine Stories (Salinger)

My Year of Rest and Relaxation (Moshfegh)

Cherry (Walker)

Small press books:

The Sarah Book (Scott McClanahan)

Hill William (Scott McClanahan)

Women (Chloe Caldwell)

Fast Machine (Elizabeth Ellen)

Big World (Mary Miller)

Ruthless Little Things (Elizabeth V. Aldrich)

Caca Dolce (Chelsea Martin)

What Purpose Did I Serve in Your Life? (Marie Calloway)

Liveblog (Megan Boyle)

Person/a (Elizabeth Ellen)

Shoplifting from American Apparel (Tao Lin)

Writers (dead):

Camus

Tennessee Williams

Bukowski

Highsmith

Dorothy Parker

Salinger

Hemingway

Scott Fitzgerald

John O’Hara

James M. Cain

Writers (alive):

Ottessa Moshfegh

Bret Easton Ellis

Joan Didion

Nico Walker

Elle Nash

Scott McClanahan

TJW: I’ve seen you talk a lot about Bret Easton Ellis (BEE). What is it about his work that does it for you? Like, reading Less than Zero and The Rules of Attraction was huge for me. Was there ever any fear that you could be too influenced by somebody in your work?

EE: What does it for me is BEE’s style. It’s like reading the New York Times on Sunday morning, perusing the New York Times Style magazine every third or fourth Sunday. You know you’re going to have a feast for your eyes when you open those thick, glamorous pages! That’s how I feel opening a Bret Easton Ellis novel. And I have no worries about being “too influenced” by him because he’s on another wavelength I’ll never get to. He’s brilliant beyond any concept of brilliance I’ll ever know. That’s not false modesty, that’s reality. Realism 101. Bret Easton Ellis is Bret Easton Ellis. Period. No competition.

TJW: “Signs,” the first story in the collection, is stunning. I love how you made the gorillas doing harmless normal things like discovering a mother’s vagina as harmless and normal as it actually is. Curiosity and developing brains. That’s not a question. Just wanted to say it. But if you want to say anything about the story I’d love to hear it.

EE: Thank you. Yeah, I think the zoo is a good place to observe and not make irrational judgments. I think we allow this sort of observation when it comes to other mammals (not humans). We don’t assign morality or ethics to the animal world. I get it: we’re supposed to be evolved, civilized. And along with evolved and civilized, I suppose, comes right and wrong. Evil as a concept gets introduced. No animal is evil. No matter how horrifying her actions. Just something I think about.

TJW: What are your thoughts on cancel culture? Sometimes I think that it actually stifles real discussion. Like that kid on American Idol being told he couldn’t compete anymore because of a video from when he was twelve surfaced and he appeared to be next to somebody in a KKK hood, but it really just looks like a pillowcase with holes for the eyes. Like, what even is that? Either way, he was twelve.

EE: Well, I’m pro-discussion. I can’t think of anything I’d be unwilling to discuss. Which is what was so frustrating to me in 2014 when I wrote that essay. No one would discuss any of the grey-area subjects I brought up (in the essay) with me publicly. I asked. People. Women. Writers. What is the fear? Of discussing things? The fear is recognizing there aren’t black and white simplistic answers to any of the great questions in life. That can be scary to people. Especially in a time of social media where what you say, in a 3k-word essay, is whittled down to a five-word summation probably not even based on anything you actually said but on a game of telephone played out over the internet. It’s a great loss to society, the inability or unwillingness to have intellectual, rational debates. It’s living in fantasyland, where everything is very clearly marked right and wrong. It’s a child’s world. It’s not real life.

Troy James Weaver lives in Wichita, Kansas, with his wife and dogs. His work has appeared in New York Tyrant Magazine, The Nervous Breakdown, Lit Hub, The Fanzine, Hobart, and many others. His books are Witchita Stories, Visions, Marigold, Temporal, and Selected Stories.

More Interviews