The Strangest of the Strange | An Interview with Mark Leyner

Interviews

By Gavin Thomson

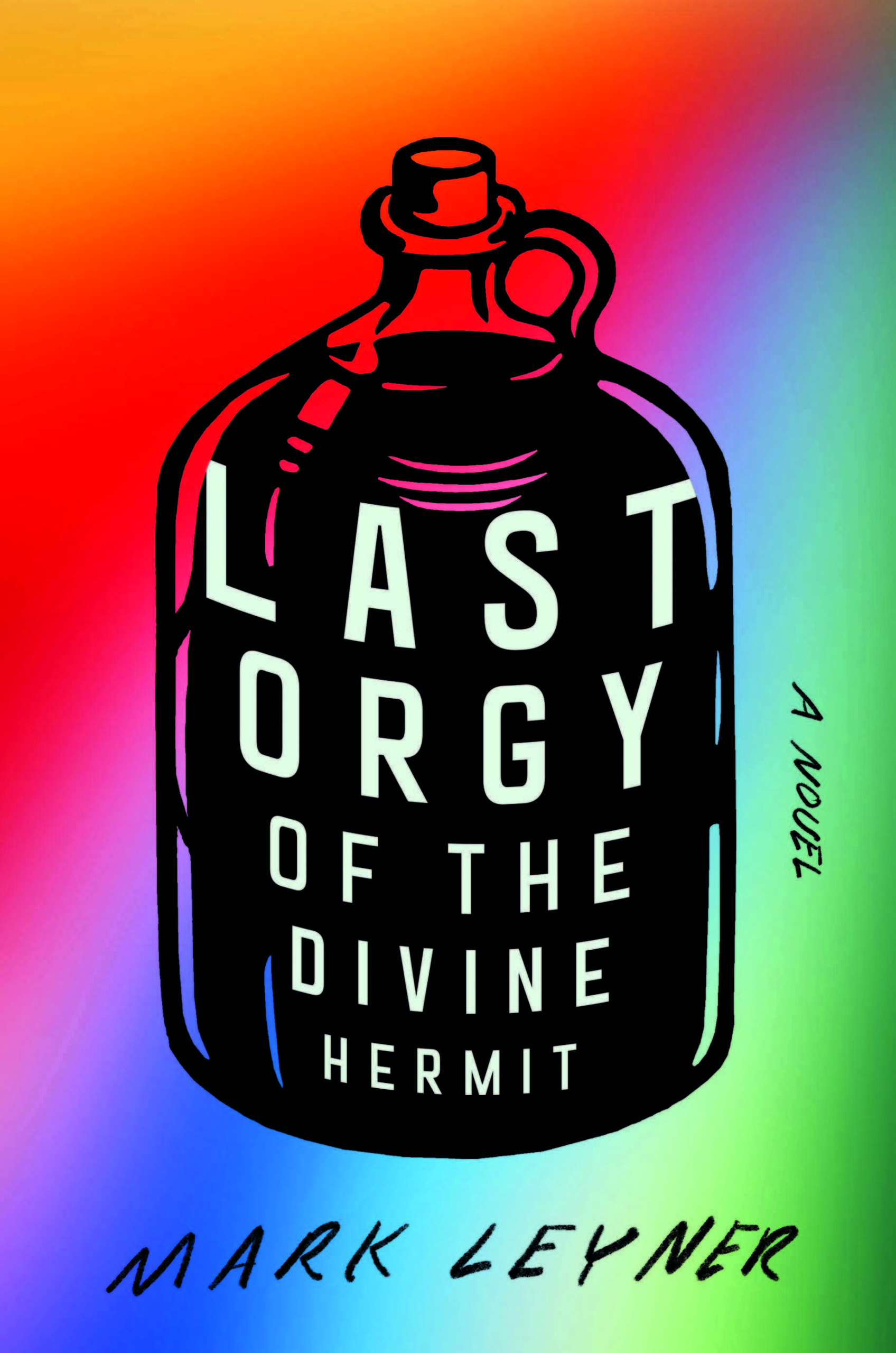

Mark Leyner’s latest novel, Last Orgy of the Divine Hermit, is unique enough to be the 119th element on the periodic table. It’s difficult to write about in the way one typically writes about a book. What is it about? If one were forced to summarize, one might say it’s about a father and daughter who take a trip to a fictional and very dangerous country to write its ethnography, also titled Last Orgy of the Divine Hermit. But that summary would not do justice to the novel’s multilayered and paralleled form.

Here are some of the novel’s other many components: an incredibly violent mafia of ex-theatre kids whose place in the hierarchy corresponds with their choice of cologne; a puppet show; academic dance criticism; an invented language made up mostly of consonants (“zcbvoiuzx bxer, noiagoewnjkg vlkrtnpojb”); a game of Fuck Marry Kill played by father and daughter (“Stalin? I’d fuck Stalin in a second! And I’d fuck his whole crew: Malenkov, Zhdanov, Kaganovich, Nikolay Bulganin, Lavrenty Beria”); poetry by Hölderlin; and a film production house called Don’t Let This Robot Suck Your Dick Productions. Add in multiple narrative modes, from stage directions and fairy tales to eye charts and books within books. (The only straightforward part of the novel comes at its very end, with the “About the Author” page. ) The novel’s breadth of references, and the sheer amount of ten-cent words it doles out, is astonishing. One gets the sense that Leyner will continue to learn in his grave.

Eccentrically erudite and symmetrically reckless, Last Orgy of the Divine Hermit is meant to be experienced, as Leyner recently told me, like a theme park on psychedelics. Mark and I spoke over Zoom.

Mark Leyner: How are you?

Gavin Thomson: A bit nervous.

ML: That’s ridiculous.

GT: Good. That’s what I want to hear.

ML: If only you knew me for more than five minutes, which you will in about four minutes, you will see for yourself how ridiculous that is. But it’s interesting for you to say that. Why do you think that is? Let’s start the interview. I’ll ask the questions. Is it something about the work itself?

GT: Perhaps it’s the work itself. You probably know this quote by John Ashbery: “The worse your art is, the easier it is to talk about.” I kept feeling, while reading your novel, that I didn’t know how to talk about it.

ML: You think it’s a hard book to talk about?

GT: To talk about in the usual ways that one would talk about a book. I had to find a sort of new language. But I will start with a very simple question, which may be helpful to those who read this interview. How would you explain your book to a high school student?

ML: I think there are a number of ways I might describe it. I would say I set out wanting to do a book that somehow involved my daughter. When I start a book, I like to have certain problems. It’s almost as if I’m engineering problems, like how would I build something that spans the distance from here to here with some sort of hill in the middle. Do I circumvent the hill? Do I go through it? I like to have certain problems so that I begin to think about solutions that might create an interesting book.

So, I wanted to write a book about my relationship with my daughter, but a book about my relationship with my daughter that didn’t breach her privacy. So how could I do that? I think young people who are fluent in and active on social media are very involved with this word “curation,” “self-curation,” with creating a persona, or maybe a multiplicity of personas. But people tend to be very careful about that. I didn’t want to come on like a bull in a china shop and vandalize her self-curation or violate her privacy. But I did want to do a book about the two of us. We’ve always been very close, in certain unique ways I think. Maybe lots of fathers think that, but I certainly do.

I also wanted to write a book that somehow involved reading, almost as a subject matter, a book about reading, almost. Now you could say, “Well, every book is about reading.” But I really wanted to focus in and do a book that’s about the phenomenology of reading. That’s what I started with, and I think somehow or other that’s what I ended up with. I think I did figure out a way to write a book about my relationship with my daughter, but looking at my relationship with my daughter almost in an anthropological way—looking at the culture or subculture that my relationship with my daughter has formed. This isn’t just true of me; this would be true of any father and daughter, or any two people, any two friends, any couple, romantic couple, or friendship. I think the relationship begets a kind of culture, by which I mean a certain private language, shared memories, shared histories, mythology: all the things you develop when you have a close relationship with someone. I realized I could make a book about that, and that solved the initial problem I just talked about.

But it’s tricky. How do you make a book for other people to read about secret languages and code words and little private jokes and all the very private intimate things? How do you do that in a way that’s not completely hermetic, that’s available and comprehensible and delightful to other people? That’s one thing I do in the book, I hope, with some degree of success.

And the other thing about writing a book about reading is I ultimately produced a book where everything that you, as a reader—or I’m talking about my high school student here, that you invented for me—everything that you’re going to read in this book is actually being read by characters in the book. It’s almost as if you’re reading the book and everyone from the book is reading over your shoulder, which is literally true. The first part of the book takes place in an optometrist’s office, and you have a patient reading the eye chart, or seriously misreading the eye chart. The second half of the book takes place in this thing I call a spoken karaoke bar, where all the people sitting around are reading screens over the shoulders of the person they’re talking to. Even though it seems like they’re having regular conversations, they’re not. They’re being read in the way you would sing lyrics at a karaoke bar.

That’s what this book is. It’s a book about me and Gaby, it’s a book about a father and daughter, told in this way.

And then there are other dimensions. It’s also a book about this fictional country, about the Chalazian Mafia Faction, an insanely violent group that’s relentlessly fighting outside the karaoke bar throughout the entire book. But those are the two basic things the book is about.

The word “about” is a funny word in relation to what I do. It’s a tricky word because I’m more concerned about the experience of reading my book than I am in the aboutness of it. I’m always thinking, when I’m writing, that I’m designing an experience, as if I’m designing a theme park for someone, or designing a psychedelic drug to take and then go to a theme park. I’m very concerned, as I work, about what the experience of reading these lines is going to be. I’m more concerned about that than I am with expressing something else.

When you were talking before you said an incisive thing—it’s difficult to talk about this book. That makes me feel good. If I wrote something easy to paraphrase, I would feel as if I had failed.

GT: You once described your relationship with readers as theatrical. You said that one of the main things you try to do in your work is delight your readers. Do you still feel that way?

ML: Absolutely, more than ever. I was very insistent with myself when I started this book that it be ferociously reckless, and that can be unsettling to certain readers. When I talk about delight, sometimes that involves being very unsettled, the way one might be watching a horror movie and not knowing what’s around the corner. Especially in this book—and I hope this is true; it was my intention—you really might not know what will happen, from sentence to sentence or paragraph to paragraph.

There were many times, working on this book, when I was about to do something and I would say to myself, “You can’t do that. You’re going to sabotage the entire book. You’re going to ruin it. You’re going to take it down.”

The coolest thing about all of this, the most interesting thing, to me and I think also to people reading the book, is that the things that seemed most dangerous to me, the things that seemed to put the integrity of the book in most peril, are the things that I loved best about the book, and that I bet a reader will find most delightful, most fun, most unexpected—these are the very things where I had to say to myself, “You’re putting the whole project at great risk.” This is what I was talking about when I talked about recklessness. I hope this book is a great testament to my willful recklessness.

GT: It’s reckless but it’s also very symmetrical.

ML: Oh, thanks. I think that, out of anything I’ve done, this book is the most precisely constructed, which is an odd thing to say having just talked about its recklessness. But structurally there’s a complexity to it. I don’t think it’s hard to read. I think—I mean I would hope—that it’s very enjoyable, a lot of fun to read. But for me it required an enormous amount of constant thinking and calculation to keep its symmetry. There’s a complicated interlacing of time and space.

GT: I was going to ask how time and space work in the novel.

ML: You have characters in a book aware of the Introduction to the book, which is an impossibility, but it makes a sort of sense in the book. It began to make sense to me when I began to say, “Well, we’re going to treat the temporal dimension of the book as a spatial dimension”—meaning, since the Introduction comes before the second part of the book, in order for the characters in the second part of the book to get there, they had to physically go through the first part, so of course they would know what’s in the Introduction. It’s almost as though the Introduction was a foyer, or an antechamber, leading to the other part of the book. By switching or interlacing the idea of what’s a temporal dimension and what’s a spatial dimension, you can do something that is at first glance completely paradoxical. But when you look at it the other way, it makes complete sense. Of course the characters would be aware of what’s in the Introduction. The Introduction already happened. In the book it did. When you’re reading a book you’ve already read the introduction, even though the introduction can only be written after the book its introducing has happened. There was an arduous complexity to keeping all this structure coherent.

GT: That reminds me of something—maybe it was Thomas Mann who said this? He said something about how one of his gifts was that he could keep in mind all at once every element of the novel he was working on.

ML: It’s a lofty association to give myself, what I’m about to say. But you brought him up. When I was in the throes of this, and this was never more true than with this book—I don’t know how long this book took me, several years—it was as immersive a work experience as I’ve ever had. I was thinking about it all day, in my dreams, waking up, falling asleep, seven days a week, incessantly thinking about it. That also meant—and I think this is what you were alluding to in that quote—that everything I would see, in the course of my day, whether it was taking a walk, going to stores (this was pre-COVID), or watching TV, or listening to music, or watching something online, or looking out the window—everything got filtered through considerations of possibilities in the book: hearing a phrase, seeing a bird do something, watching a documentary about Philadelphia crime wars, everything, literally everything, got put through this sort of filter. I had to have a reckless criteria for allowing things in, not quite knowing what they’d do once they were in there. But, getting back to your quote, I would know exactly where something would go, or where I would want to try it. I knew the book and processed everything in it, down to the words and where they were. It’s a bit like the chess grandmasters who can play simultaneous games with people, and keep track of all the games. If things are going optimally well for me, that’s how I’m feeling about the book I’m working on. I know the fifty, the hundred, the hundred and fifty games being played, all of them. I’m playing them simultaneously.

GT: I got the sense while reading the novel, and now I get the sense even more, that when you’re conceiving the book, it’s a very visual thing for you—that the form of the novel appears in your mind on a visual plane, with shapes.

ML: That’s true, exactly and precisely. I will usually have an architecture, a schematic and visual understanding of something long before I’m even certain of anything that’s going to “happen.”

GT: There are, as you’ve mentioned, many realities taking place at once. They reflect each other, communicate with each other, parallel each other. When I read the novel, the characters are reading, and I’m reading what they’re reading; everything is reflecting back and forth. Does your novel formally resemble a particular shape? Is it a fractal? Is it, to use a quote from the novel, “a mirror from which there is no escape”?

ML: Probably some sort of fractal structure, or a mise en abyme, or a Chinese box, or a Matryoshka doll—something like that. Do you know those lenticular screens? They used to come in Cracker Jack boxes. They’re finely ridged, so if you turn one slightly, you get a different image. I like to think of this book, and more than any other book of mine, as lenticular. From one angle, it’s a very conventional story about a father and daughter. Then they go abroad to do research on a very violent group, the Chalazian Mafia Faction, and they go to a bar in the capital of this country, and outside the bar this group is most active. It happens to be father-daughter night. The daughter’s boyfriend is going to at some point swing by and pick her up, which in a certain way makes absolutely no sense, given the fact that he’s coming from Long Island or something. But on the other hand it makes perfect sense: a daughter’s hanging out with her father and later in the night a friend or a boyfriend is going to come by and get her. It makes perfect sense.

Something entirely surprising happens, before the daughter leaves, which is kind of out of a crime novel or film noir. I’m not going to say what it is, because unbelievably there can actually be a spoiler alert in one of my books, which I never thought I would say. So yes, we can look at it as a book of successively enclosed fractal structures, or a mise en abyme sort of thing. But also it functions shockingly as a bit of a thriller, with a very legible storyline.

GT: I know what you’re referring to, but I can’t mention it without spoiling.

ML: There is a way of looking at the book as a thriller. There’s also a space-time impossibility to it. There’s almost a comical simplicity to the father’s anger and why it happens. But, again, when we’re talking about an introduction, and the writer of an introduction, and what happens later—I don’t want to ruin it—it’s both patently simple and accessible to anyone. At the same time there’s a real conceptual, delightful problem to it happening together. But you have to read the book to understand how you never could have predicted how it happens.

GT: You’re in a world of your own. There’s no writer who seems to eclipse what you’re doing.

ML: Thank you. For most writers this isn’t true, but it’s extraordinarily important for me to be absolutely, incontrovertibly unique. It means everything to me to be the only one doing this, and it requires me to keep myself apart. In my life it requires a solitariness, an aloofness, that I think is unhealthy for me as a human being. But it has enabled me to produce work that is, as you said, unlike anything.

GT: So you yourself are a hermit?

ML: I have friends but not many. I’m very okay and comfortable with being by myself. There’s a play by Sophocles, I can’t remember which, but there’s a passage where Sophocles talks about mankind as being strange, unlike anything, unlike any other creature, unlike the gods. Heidegger translates what Sophocles says as “the strangest of the strange.” It’s a beautiful quote. To do the work that I’m trying to do, I need to be the strangest of the strange. It requires keeping myself apart, to a large degree. It’s not like I’m some sort of dangerous recluse whose house children have to avoid on their way home. I’m also shy. I don’t think you choose the life of doing something that requires an insular working life—I don’t think you choose that if you’re an enormously jovial, gregarious person. You would do something else. But I’m particularly okay with being solitary.

Gavin Thomson completed his MFA in fiction at Columbia University, where he was a Felipe P. De Alba Fellow. He is at work on his first novel.

More Interviews