Wu-Tang Is for the Children | A Conversation with Big Bruiser Dope Boy

Interviews

By Conor Hultman

The poetry of Big Bruiser Dope Boy hits you like an elemental force. Other writers announce their presence off in the distance. You’ve seen their names on book jacket blurbs, heard their voices on NPR, known people at school that haven’t read them but use their name as a descriptor, “___-esque.” No, I had never heard of Big Bruiser Dope Boy. Then my friend gave me his first book of poems. I was hooked. I bought every book he’d published and read them with a rapt and gleeful appreciation, all while kicking myself for having been in the dark for so long.

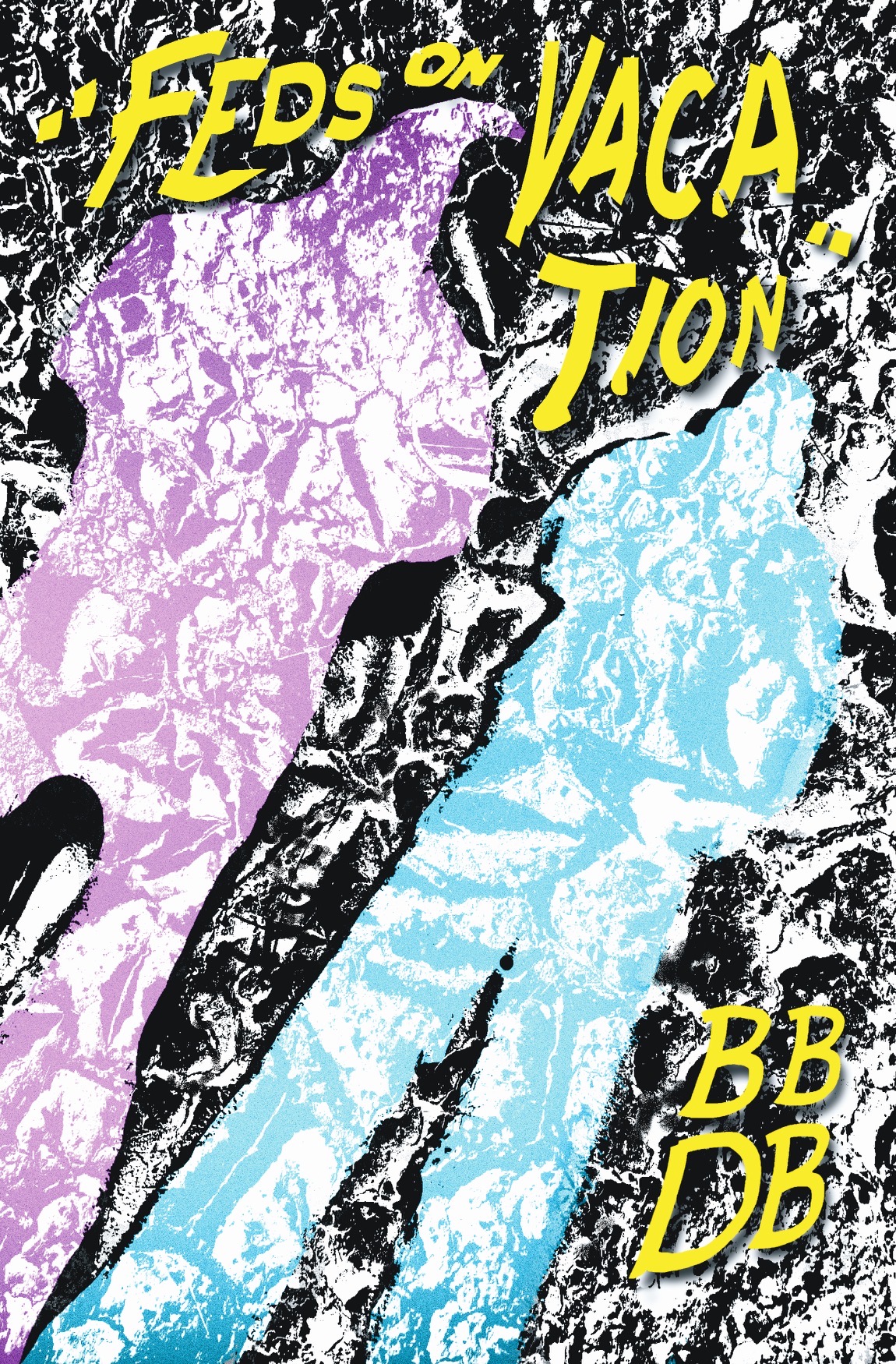

In March, BBDB came to Oxford, Mississippi, for the annual Conference for the Book. He was supposed to give a reading from his new poetry collection, Feds on Vacation. But the National Weather Service issued a tornado watch; the sky turned an apocalyptic, mustardy yellow, and every business on the town square was closed and deserted. Except for the venue, that is: a record store called The End of All Music. Myself and a couple dozen other patrons risked cyclonic destruction to hear Big Bruiser Dope Boy. If you read the book, you’ll see why. I interviewed him recently over text about Feds on Vacation and writing in general.

Conor Hultman: Most of the poems in Feds on Vacation are about people close to you: friends, family, lovers, those alive and dead. But “How to Spot Feds in Art Spaces” is about the people furthest from you: vultures, frauds, enemies. Does that poem come from another place creatively than the other poems?

Big Bruiser Dope Boy: That one felt like the title/flagship poem—the main node. You say it’s about the furthest people but I don’t know. I think part of it is about the closeness of it all to the point where anybody can be that potentially, including and especially you.

The content and tone of the poem are different in ways than the others, but I think those themes seem to run (not on purpose) through the rest. I can’t say it came from a different place creatively than the others. It’s difficult to account for where things come from other than wanting to do something good, that I like, that feels meaningful/important/valuable/vital.

CH: That poem also is about fake artists, or those who seem to be writing for motives other than passion or self-expression. Is it possible for writing to be inauthentic?

BBDB: I mean, yes, it’s possible for writing to be many things, including that in the sense you describe. Authenticity is also a social fixation. Everybody calling each other “real ones,” etc.

CH: I remember seeing you read the poem “Fable of a Personal Nature” in Oxford, back in March. The poem is about doing methamphetamine with a gay hookup. I remember watching the faces of people in the audience while you were reading it; their expressions went through an incredible transformation from amused to disturbed to deeply moved. How do you think about the reaction of the reader or audience when you’re writing?

BBDB: That’s funny. I was staring at what I was reading so I didn’t see any of that, but my friend who was there told me he saw a guy get this appalled look on his face, shaking his head and looking around for solidarity in others. I think there’s a stage in editing where I’m imagining myself as a stranger reading the work and tracking what it’s doing/its potential effects.

CH: I think that’s what’s so dynamic about your writing: that the voice is challenging and uncompromising. The poems in this book don’t care whether they offend with their perception of others, their queerness, or their challenges to authority. Have you had any pushback to the candid and provocative aspects of your writing?

BBDB: There’s been a little pushback to some of my writing, I guess, but not that much really. Nothing really direct. It’s mainly just ulterior resentments, emotional skews without substance in the writing scene. On one hand, people have been talking passive-aggressive, snarky brat shit about my writing since a poem called “55 Remakes” (later expanded and renamed “69 Remakes”) was published on the now-defunct/doxxed Fluland and became relatively popular because people loved it and that made other people feel bad about themselves and pissy at me. But, for the most part, I think people know it’s all love. That it’s art, poetry. It’s a heightened, framed, figurative, abstract expression. And that, independent of that, I’m a person who is alive, open, and not that hard to find. Someone who will talk through pretty much anything with anybody. It’s also not that big of a deal. Art can do a range of different things, and people can determine its value through a range of different systems. It’s a small-press poetry book. Five hundred people tops will probably ever actually read it. I would think people have more pressing life things. If people want to get worked up or grant credence to it, that’s fine, but it’s also a consequence of them. It’s not as if there’s a multibillion dollar company astroturfing my work and thrusting it into people’s consumer consciousnesses. Readers come to me; I don’t come to them. Very few people will read this interview, and even fewer will buy and read my books because of it.

CH: Do you believe in artistic manifestos? Should a writer have clear intentions and aesthetic principles before beginning to write?

BBDB: I think manifestos can be awesome. Polemics can be amazing. I believe in the potential power and truth of that form. I also think that stuff is often theoretical scaffolding to get back to the creative act. Which isn’t to say that it can’t be a creative act itself—writing your way back to writing. The thing for me is seeing that it doesn’t become a dogmatic hindrance/trap.

I’m not sure on the second part of that question. Does “before beginning to write” mean before a writer ever writing at all in their life or before a new project or what point in time? I don’t know what writers should have. But I’m not sure if it’s totally possible to do what you describe before the act of writing. And I think that if those things become clear, they become clear in the duration of it. It’s like the scaffolding thing.

CH: Is place important to your writing? I ask because place seems to be foregrounded in some of your books, like After Denver and Something Gross, but I’d be hard-pressed to define you as a regional or national writer, if those terms are even useful anymore. I’m interested in what your thoughts are.

BBDB: Things happen in specific places and those places have qualities. As things become more homogenized and atomized, the meaning of place changes. In terms of being regional or national, I think a lot of what I do is pretty American, and also French.

CH: You’ve said online recently that one of your poems is going to be taught in an 8th-grade class. How does that feel?

BBDB: Wu-Tang is for the children.

CH: What do you make of the publishing industry as it stands today?

BBDB: I think it’s mostly propaganda and memoirs, and that the literary imprints are designed to lose money on fangless, insipid, innocuous titles authored by media inventions which are tax write-offs to widen the margins on the more widely disseminated mindfucks.

CH: What about independent publishing? Is it any different? If you were a publisher, what kind of writing would you be interested in putting out there?

BBDB: Indie presses are better than big ones, but only if they’re born of necessity and tempered with a good ego. The worst is a small press aspiring to be like a bigger one with an overproduced businessperson-type at the helm. In that sense, big presses might be better than small ones because there’s not the element of petty ego shit. Self-publishing is the best in terms of control. If I was a publisher, I’d be interested in publishing writing that I like.

Conor Hultman lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

More Interviews