Tectonic Punch Lines: A Conversation with Ryan Ridge

Interviews

By Abraham Smith

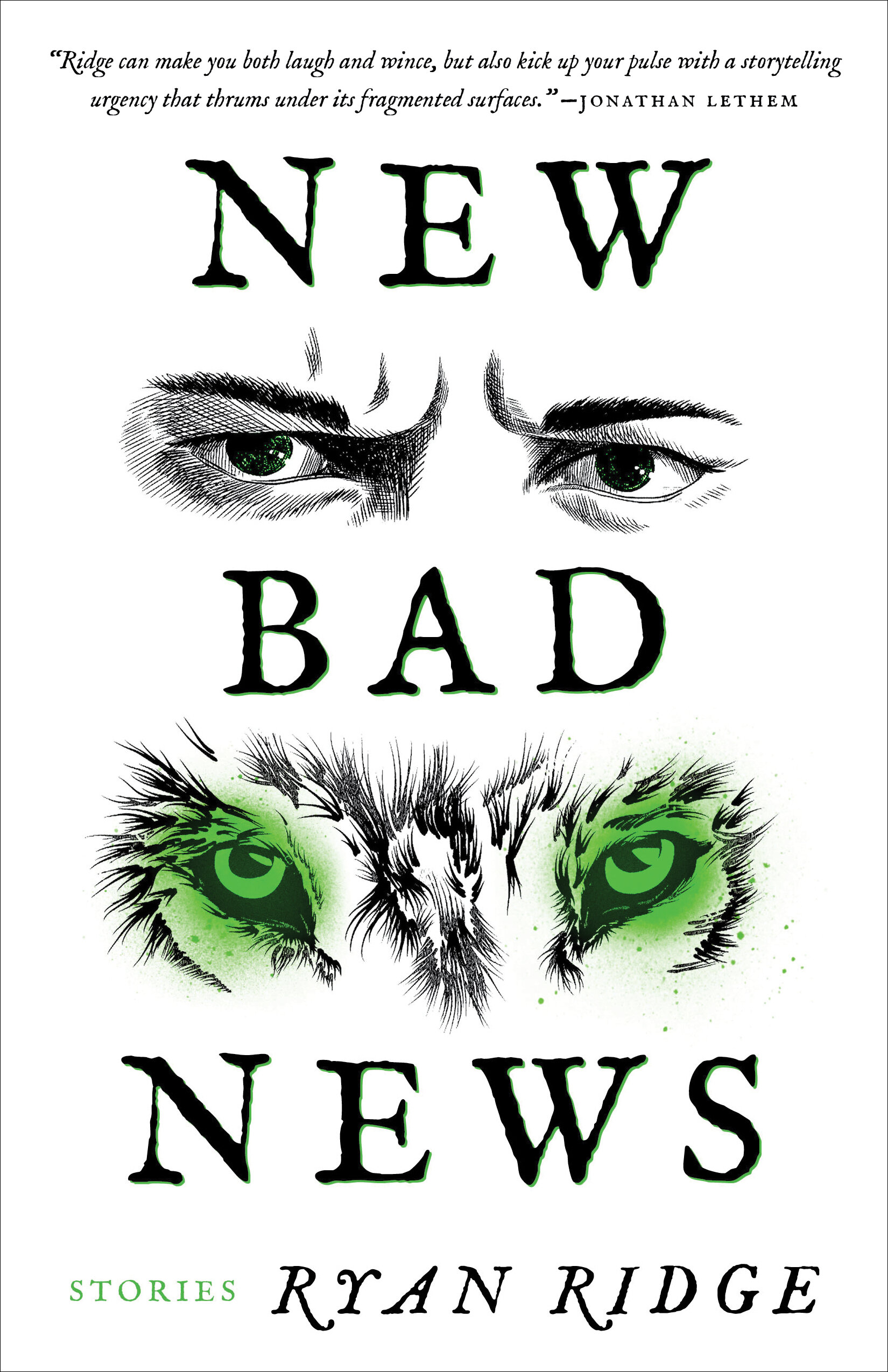

Ryan Ridge’s New Bad News (Sarabande Books) arrives today at a bookstore near you. Packed with soul-pathos and crackpot humor, Ridge’s latest is a must-read for our times. In fact, you might call this one downright prophetic. Everything awaits inside, kitchen sink leak synth included: the quickest wit in the West; tinsel town’s hissing mirages; dreams deeply American; cheap beer good and cold; downbursts of social commentary; scalpel-fine finessing of the human condition; wisdoms poached and wisdoms boiled and wisdoms deviled and wisdoms parboiled. Readers are encouraged to keep a cry-laugh hankie very, very handy.

Abraham Smith: A few years back you won the Calvino Prize in Fabulist Fiction. Jonathan Lethem picked you. New Bad News picks up with an epigraph from Calvino. In what ways do you see yourself as a farmer of crops in Calvino Fields? And in what ways do you consider your work to be a departure from Calvino Way?

Ryan Ridge: More than a handful of years ago, my buddy Kyle put me onto Calvino’s lecture “Lightness,” which appears in Six Memos for the Next Millennium. Kyle said something along the lines of: “This is what I see happening in your work. Take a look.” In the talk Calvino describes the world around him turning to stone, and then he says, “Whenever humanity seems condemned to heaviness, I think I should fly like Perseus into a different space.” He goes on to advocate for lofty literature that rises like a bottle rocket in the breeze, unburdened by the accumulating heaviness of our days, and this ascension, this explosive lightness, is what causes a shift in the reader’s perspective. I think I’m after that same shift in my own work, too, but rather than magic carpets and nonexistent knights, I’m more interested in downwardly mobile suburbanites. So, I’d say Calvino taught me the method, but I have a different means since I incorporate a more American mythos, which carries with it a different set of archetypes and concerns.

AS: You are a giant of the one-liner, often driven by chiasmus. An atomic aphorism master if you will. And a great many of these knock the reader off the chair with a case of the giddy titters. Your comic timing is darn near peerless. These piths seem to unspool intuitively and effortlessly from your dagger-plume. What’s the biggest appeal of the zinger for you and can you trace a little your study in it?

RR: Aphorisms and jokes are like maps comprised of detours: you always end up somewhere unexpected. Therein lies the charm. I like to be surprised. My education started with Richard Pryor. I loved his joke about the time he met Ronald Reagan: “I went to the White House, met the president . . . We in trouble.” That’s a complete short story to me—beginning, middle, and in the end, Pryor takes a hard left into irreverence. I also studied the way Steven Wright’s jokes lapsed into surreal fables: “I went to a place to eat. It said ‘breakfast at any time.’ So I ordered French Toast during the Renaissance.” Or Mitch Hedberg: “I’m an ice sculptor. Last night I made a cube.” In both of those examples, the last word is most important word. The aphorists know this trick, too. Take William Stafford: “Rocks that fail become sand.” Philosophers as well. Here’s Lichtenberg: “There are very many people who read simply to prevent themselves from thinking.” For better or worse, I’ve made a lifelong study of the line. It’s definitely helped with my short work, but it’s made the novel-writing process hell.

AS: “Had a job that ran counter to her passion,” you write. CA is the perfect frame for this spectral Dream work. Land where folks head to make it. And sometimes do. And often don’t. Thinking about this from the writer’s point of view, what’s your definition of making it? And has that changed over time?

RR: I think “making it” for me means to continue creating work that feels interesting to me in the moment of composition. As long as I’m taking risks and not playing it safe, I think it’s a win. I never had any grand ambitions to be on the bestsellers list or anything like that. I write experimental fiction with language at the forefront, much of it short, and occasionally collaborative. That kind of work won’t earn anyone an international fan club. I’ve always looked to the late Harry Dean Stanton’s acting career for the type of writing career I’m after: you peruse his IMDB and quickly see a lifetime of exciting work. He made a ton of movies, always working, and other than Paris, Texas and Lucky, he was never the star. The critic Roger Ebert had what he called The Stanton Rule, which operated on the assumption that “no movie featuring Harry Dean Stanton in a supporting role can be altogether bad.” The goal for me is to keep working and never bore anyone.

AS: It takes about seven seconds of sleuthing to discover that you are a much-beloved, much-revered professor. What’s one piece of advice you routinely dole to students but rarely heed; and what’s an axiom of your classrooms that you follow most writing days?

RR: My only actual teaching (other than don’t be boring) rule is that there aren’t any hard and fast rules on the page, that for every literary policy I can think of, there are at least a dozen exceptions. For instance, it’s generally considered a dunce move to start a story with a character waking up, but Bowles begins his masterpiece Sheltering Sky with that very action. Willy Vlautin starts two of his novels (Lean on Pete and Don’t Skip Out on Me) with characters waking up, and he pulls it off, so I just attempt to raise awareness to things that can present challenges to newer writers and show them how other writers have faced similar challenges. But for a guy who claims there are no rules governing stories, I find myself abiding most of what old Aristotle professes in the Poetics, especially his ideas about unity in dramatic structure.

AS: Here and there, you hit so perfectly on the hidden obsequious sycophant inside of each of us when faced with might-be fame. And that place inside of many of us that just wants the answers; wants a little or lot to be told what to do. As you scroll through the Rolodex of your days, what’s some of the worst advice you’ve received and the best?

RR: Best advice? An old boss once told me to have a plan by the time you’re thirty.

As per lousy advice, I can’t think of any specific instance, but I remember my high school teachers constantly extolling the absurd idea that those years would be the best years of our lives, which is total horseshit. My teenage years were an absolute nightmare, and my twenties were worse. My thirties were fairly chill, and I love my early forties. Life gets better and easier, albeit more and more absurd.

AS: Kirkus Review calls you tinged by Bukowski. I can smell a little of the hard-boiled Buk in here. And certainly there’s ample darkly lit bar drinking going on. And more than a little whiff of Buklike despair. But this more often reads to me like your right hand is Barry Hannah and your left hand is Gertrude Stein. Who’s the person/s at your Literary Family Reunion that we’d be least likely to guess? But they’re there dang it, and drunk, and about to fall on the makeshift cardtable?

RR: Okay, so there’s this guy Jack Douglas. He wrote jokes for Jack Paar and Johnny Carson for a living, but in the late-50’s he published an insane postmodern memoir called My Brother Was an Only Child. He followed it up with some less successful efforts, but the My Brother book was a big influence and one that I don’t talk about much because I’ve never met anyone who’s ever heard of Jack Douglas. A genius in my book.

AS: New Bad News is the perfect book for our times. And frankly not one stadium din laugh-track moment can drown out its deafening sorrows. This book rides the rims of the bull’s-eye aimed at those whose lives are underwhelming almosts and at loggerheads. There’s so much proximal distance; and indictments of the America we live around the corner of every page. It’s been a sharkish whale of a year and we are only one-third of the way on in. What’s the oldest book or music you turn to for hope? I guess I am asking for a little old good news, compliments of RR!

RR: The late-great John Prine is better than benzos . . .

I started typing my answer to this question in our office at the house, and as soon as I did, boom, a copy of David Berman’s Actual Air came crashing off the shelf. We’d had another little earthquake. Ashley hollered back and asked if everything was all right. “It was David Berman,” I said. Now it seems remiss not to note that his songs and poems, although dark, fill me with a deranged sort of optimism. I also think that James Baldwin, Joan Didion, and Hunter S. Thompson are three writers I intend to revisit in these COVID times.

AS: The great literatures of witness down through the ages have so often leaned on the satirical cut of the jib. My last question then: Did you set out to make NBN into a literature of witness? In the Blakean sense, it is prophetic.

RR: I suppose all literature is a literature of witness to varying degrees. It’s just a question of magnitude. I’m not afraid of being didactic in my work, and I guess that in the end, I aspire to timeliness over timelessness, so to answer your question: maybe.

Abraham Smith’s recent work includes Destruction of Man (Third Man Books, 2018) and the forthcoming chapbooks Bear Lite Inn (New Michigan Press) and Touchstone Blues (The Condensery). He lives in Ogden, Utah, where he is Assistant Professor of English and Co-Director of Creative Writing at Weber State University.

More Interviews