Show Me Your Shelves | Theo C. Van Alst

Interviews

“Show Me Your Shelves” is a regular book column by Gabino Iglesias. In this edition he talks with Theo C. Van Alst, author of the Sacred Smokes and Sacred City.

I don’t remember when I first met Dr. Theodore C. Van Alst. But I do remember everything else: reading Sacred Smokes and loving it; interacting with him to the point of calling him čhiyé (older brother in Lakota); and eventually reading Sacred City and having the honor of blurbing it. Here’s what I said about that book: “Sacred City’s swagger is as sacred as it is profane. Van Alst’s writing is ancient blood screaming through the streets of Chicago. This is more than literature; it’s history, love, violence, ancestral knowledge, and brotherhood thrown on the page with the power of a Molotov cocktail and the precision of a lyricist. I’d say something about transcendence and the universe, but this book taught me not to think so small.”

In any case, Van Alst is a superb writer, a great educator, and a photographer whose work inspires me. Now that his latest novel is out there, I thought this would be the perfect time to talk about what’s on his shelves.

Gabino Iglesias: Who are you and what role do books play in your life?

Theodore C. Van Alst: I’m a writer and a professor. Books are the life.

GI: When did you decide writing was the thing for you?

TVA: I used to write in my early 20s, did some readings at punk rock bars, mostly essays, rants, the obligatory poetry shot. And then . . . life had other plans for me. I needed to work and go to school, be the best provider for our family I could be. But a couple of literary big brothers and especially my wife were like, “You need to write these stories down.” So I finally did. And those stories haven’t stopped. They keep coming. First book at 53, new one out now. Finished a third, almost done with a new novel. Wrote a graphic novel. A novella. Putting together a massive James Michener-sized novel. Stories coming up in mags and journals. Shane Hawk and I are putting together an anthology of Native dark fiction with some big hitters. I’m a lucky guy.

GI: Can you give us a few early favorites? Any of those still on your shelves?

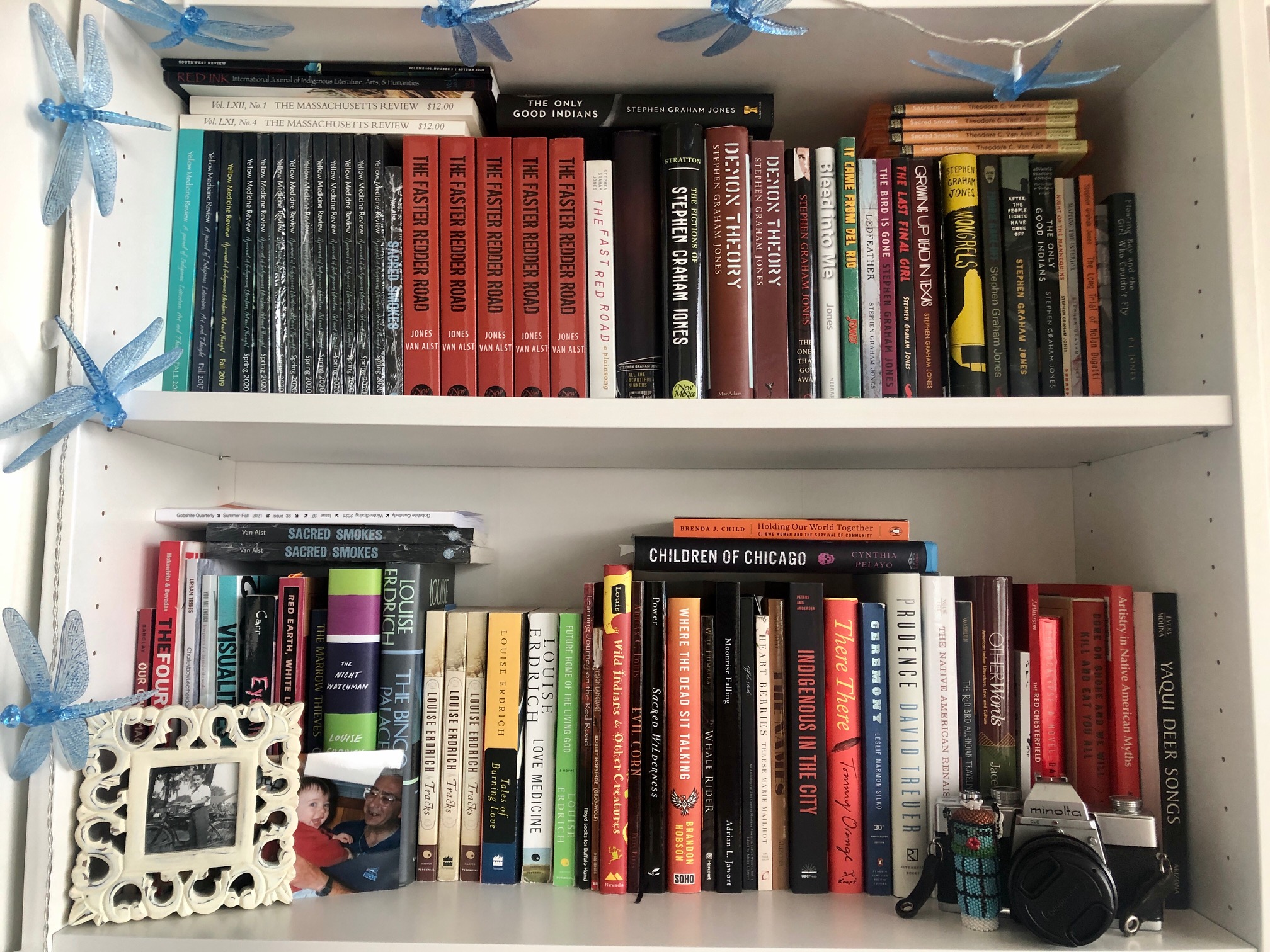

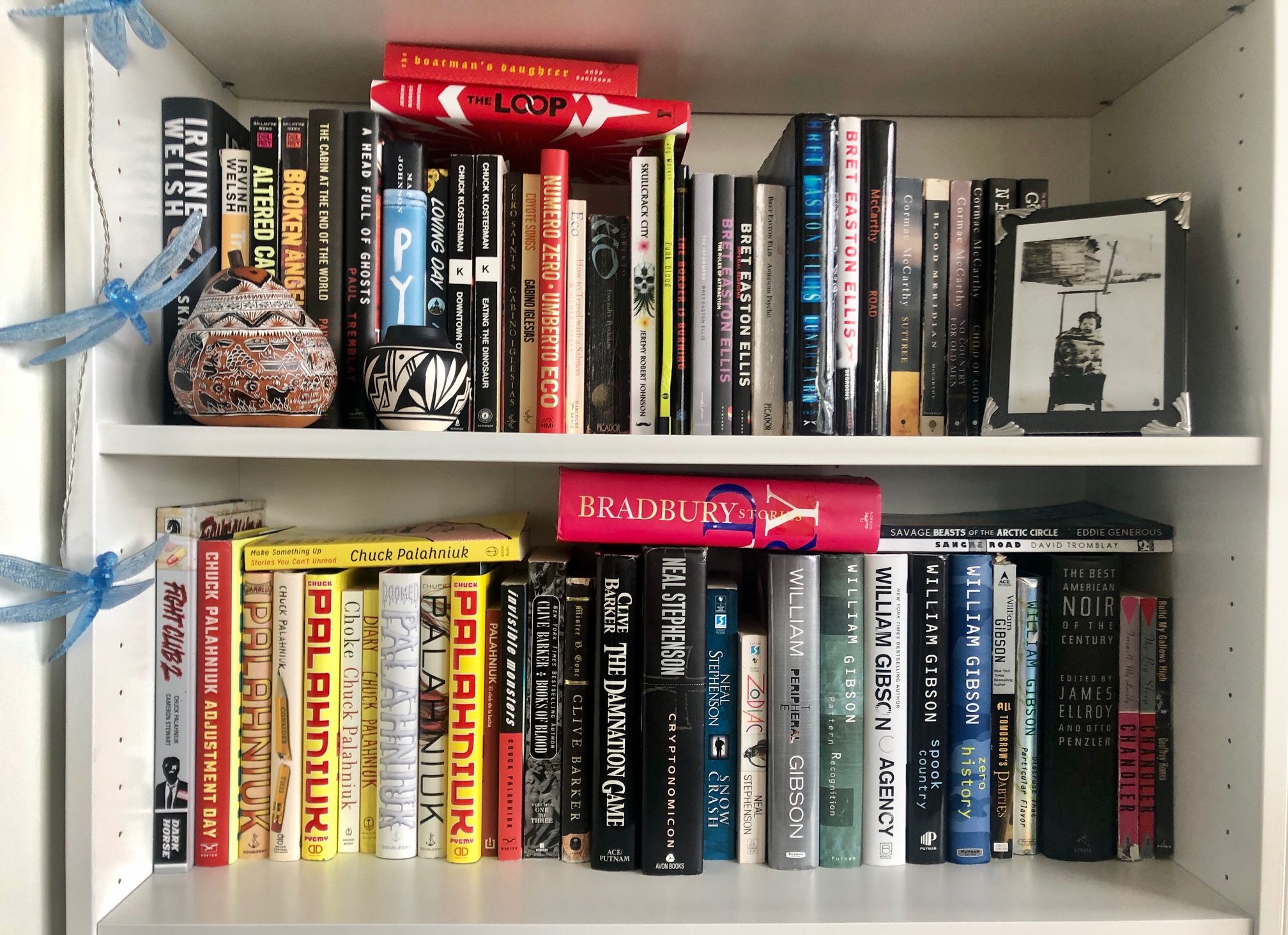

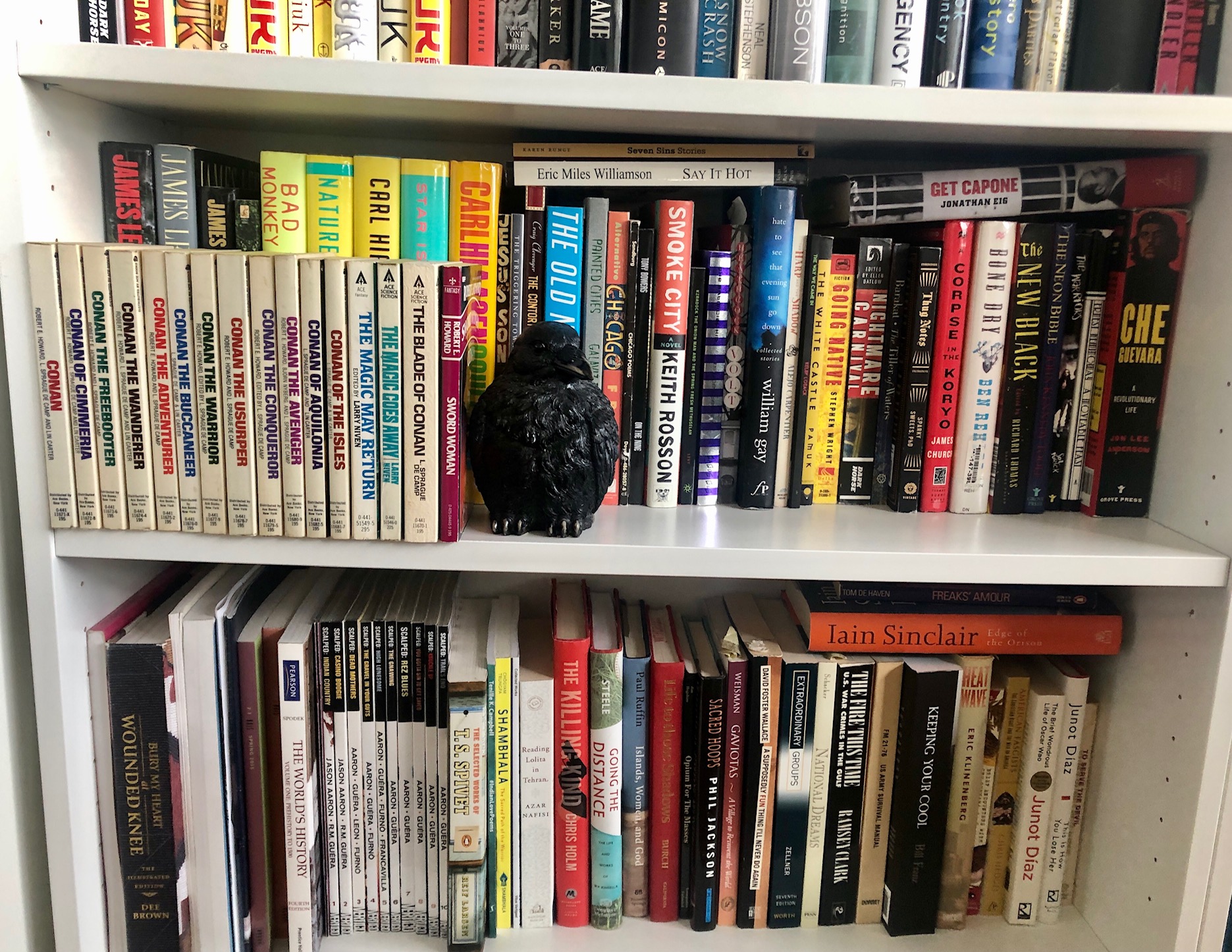

TVA: Man. I started reading when . . . I don’t remember not knowing how to read. My ma said I was three and scared off a babysitter who was like “He’s reading the newspaper. And not the comics!” If we take it back to grammar school: dinosaur books! Then: “The Monkey’s Paw”; “The Devil and Daniel Webster”; “Letters from the Earth”; “The Ransom of Red Chief.” Plus every book on Chicago gangsters I could find. During high school age (I dropped out, so I’ll throw a year or two on there), I’d say: A Confederacy of Dunces; Bukowski; “The Sun Dog”; “The Veldt”; “Burning Chrome”; The Books of Blood I,II, & III, especially “The Yattering and Jack”; “In the Hills, the Cities”; “Midnight Meat Train”; Neuromancer; A Clockwork Orange; and “The Jaunt.” Hey. Looks like I’m not a fan of novels maybe (for real, I’m not a huge fan), but early hits include: Geek Love; Less than Zero; Tracks; The Talented Mr. Ripley; The Basketball Diaries; The Talisman. I think I still have most of those, except the dino books (I should fix that.), the O.Henry, and The Talisman. Oh, shout out to The Great Shark Hunt, Danse Macabre, and “The Road Virus Heads North.”

GI: Native American literature is like horror in that it has never not been there, but folks are (re)discovering it right now. Authors like Erica Wurth, Joy Harjo, David Heska Wanbli Weiden, Shane Hawk, N. Scott Momaday, Stephen Graham Jones, Brandon Hobson, Layli Long Soldier, Tommy Orange, Billy-Ray Belcourt, Elisa Washuta, Kali Fajardo-Anstine, Tommy Pico, and yourself, to name a few, are putting a spotlight on it. Why do you think the reading public is finally paying attention?

TVA: If we think about American literature, they get their first novel in what . . . 1789? Almost two centuries after they showed up here? The first English novel was Le Morte d’Arthur in 1485, so I think we’ve closed the expected gap considerably. There are cycles of Native lit to be sure, with early offerings from Samson Occom and William Apess on down through John Rollin Ridge and Zitkala Sa, John Joseph Mathews, and D’arcy McNickle, up through Louise Erdrich, Leslie Marmon Silko, Gerald Vizenor, and N. Scott Momaday. But we’re at a moment where Indigenous concerns are more widely becoming the concerns of the overculture. Water, the environment, mascots, racism: all of these are Native issues with stories tied to them. After a few generations in the cities, it’s enough of a home that we’re comfortable writing about our lives there. That’s why Urban Native Lit is coming into play. It’s time to hear all these stories from Native writers. The affinity for horror is post-apocalyptic. Native folks are living in it, and if everyone else doesn’t smarten up, they’ll be living in it too.

GI: One of my favorite things about your work is how tied to the streets it is. Folks often expect narratives written by First Nations authors to be about them living on the reservation surrounded by buffalos or some other well-worn trope. How do you approach communicating your deep roots in your culture while also being true to your experience growing up on the streets of Chicago?

TVA: Yeah, those stereotypes are deep and difficult to dislodge, but the reality is that Urban Native populations are huge. The U.S. had a Relocation Program to try and break up communities and concepts of communally held land (it was the 50s and the “comm” was the enemy back then, so . . . ). The net was lots of folks moved to the cities. But Native folks remain Native wherever they are. Communities were rebuilt, reconstituted. Sure, they looked and sounded different because so many different tribes were represented (over 120 in Chicago), but they were and are Native communities. And it backfired on the U.S., because their worst enemy in 75 years—the American Indian Movement—was born in Minneapolis.

My work engages with Chicago, a place that has always been Indian Country, and it tries here and there to describe the difficulties that young Native folks encounter in connecting and reconnecting with their traditions. The new one, Sacred City, is even more interested in this, as the narrator grows in his awareness and understanding of the city and the world more broadly. The routes and roads and lives it’s built on burn through into the present.

Chicago is an amazing place, the greatest city in the country. I think about it every single day. Its history, people, place. Wow. I’m proud to be from there, and so is almost everybody else I’ve ever met that was born and raised in the city.

GI: How did Sacred Smokes come about, and how would you pitch it to readers who have never read your work?

TVA: That first book took a lifetime to write. Responses and reviews have been generous and wonderful. Like, you know yourself plenty, but it’s an amazing feeling to hear from folks who get your work. If I had to pitch it, though, I’d say . . .

“Here is a book full of folks you might know, might not, but should. These are stories that work to tell the stories of people whose stories don’t get told enough. If you want to learn about city life, doing your best to get to the other side of youth, and appreciating the things you have, this one might be for you.”

GI: The house is on fire. Everyone’s outside and safe. What books do you grab before running out?

TVA: Probably the signed ones. I don’t have many, so the few books with Louise Erdrich, Bret Easton Ellis, William Gibson, and Chuck Palahniuk signatures would be easy to carry. I lost my signed Clive Barker first edition Damnation Game in one of my endless moves, so just the ghost of that one, I guess.

GI: I rarely get to talk photography with fellow writers who also happen to be photographers. What does photography mean to you? Why do you capture images and share them with others? Does photography inform your writing in any way?

TVA: I mean, as a fellow photographer, we could get snooty and do a take on Edward Hopper’s quote—“If you could say it in words there would be no reason to paint.” But there’s more to it than that, because we believe there are words, or might be words, sure, and there is this thing we do as writers where we want our readers to do some work, do the fill, imagine the smell and the sound even as we’re in their ear whispering part of the story. Photography does that, too. It says, “Look at this image. What do you see? What do you hear? What do I see? Where was I going? Where have you been?” Photography gives answers and asks questions; it works to engage its viewer. And, like writing, it tries to frame indescribable moments in understandable ways.

GI: You’re also deeply involved in academia. Give us ten books you think everyone should read, especially if they’re trying to become better writers.

TVA: A Clockwork Orange. Less than Zero. Trainspotting. The Talented Mr. Ripley. Blood Meridian. Tracks. Hollywood Wives. The Triggering Town: Lectures and Essays on Poetry and Writing. Snow Crash. Neuromancer.

At first, I thought: “Well sure, those are some of your very favorite books*, and that’s not what you’re being asked.” But it is what I’m being asked. These are great books. They don’t just teach you how to write, make you think about how to write, see how to write. They also make you love to read, to experience the joy of words as art, and to create them yourself with the love and seriousness they deserve. And, man, isn’t that what it’s all about?

*Also see all the ones up top.

GI: The pandemic isn’t over, so how are you planning on getting the word about Sacred City out? How can folks help now besides buying it?

TVA: Fingers crossed it’ll get reviewed in cool places by cool people. I’ve done remote readings of Sacred Smokes for lots of places and those are always fun, so I’m hoping I’ll get asked back. If enough folks get it figured out, we might be able to go back to in-person readings. I can’t wait for those.

And, of course, I’ll follow the lead of our Twitter maestro, Dr. Gabino Iglesias, mad scientist of social media and eternal champion of the writing life.

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, professor, and book reviewer living in Austin, Texas. He is the author of Zero Saints, Coyote Songs, and The Devil Takes You Home (forthcoming summer 2022). You can find him on Twitter @Gabino_Iglesias.

More Interviews