Ecstatic Boredom | A Conversation with Daryl Lim Wei Jie

Interviews

By Greg Brownderville

In late spring 2018, I had the honor of serving as writer-in-residence at a writers’ and artists’ colony called The Lemon Tree House in Camporsevoli, Italy, a small village in Tuscany. Part of my job was to meet individually with writers and discuss their work—that is how I got to know the poetry of an author from Singapore named Daryl Lim Wei Jie. As it happened, Daryl and I were housed in the same villa so that, by the time we met to talk about his poems, we had already enjoyed several lively conversations. When I received his writing sample in advance of our first formal meeting, I was much taken with the strange voice in his poems—unsettling, hilarious, daringly variegated.

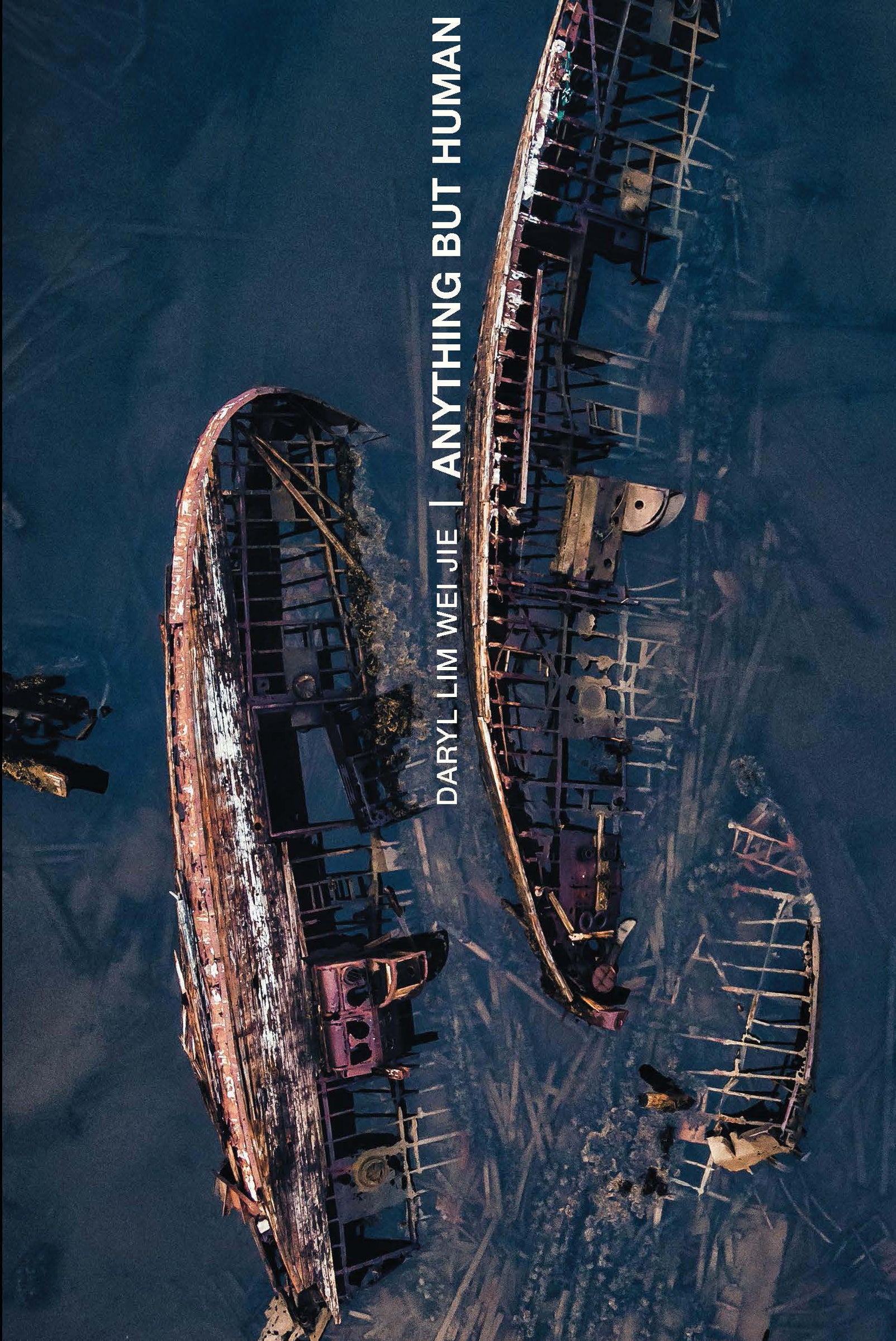

Recently, when I found out that his new book of poems, Anything but Human, had been published, I devoured it and found myself being dazzled again and again by the inventiveness of Daryl’s lines. To explore the weird carnival of urban life, Anything but Human often revels in the banal language of advertisements, inspirational slogans, and policy documents. The voice is delightfully disconcerting—often comic with an ominous undertone. Reading the book, one begins to feel that the apocalypse is brewing but that we’re far too distracted by modern mind-candy to notice or care.

Naturally, I wanted to talk with Daryl about the collection and figured I might as well let SwR’s readers in on the fun. One quick note: there is little to no redundancy between the text and video below, so be sure and check out both portions of the conversation to get the full dose of Daryl’s brilliance.

Greg Brownderville: Reading “Anything but Human,” I remembered this sentence from Pablo Neruda’s “Toward an Impure Poetry”: “Those who shun the ‘bad taste’ of things will fall flat on the ice.” On one level your book strikes me as a critique of our fastidiously disinfected, comfortable modern lives. “The city is mild and scentless,” you write. The speaker and the nation-state are both “wiped clean of atrocities.” Of course, your poems don’t stop there. They often spotlight the disgusting stuff that modernity suppresses. Could you talk about how these motifs play out in your book?

Daryl Lim Wei Jie: When the art critic Arthur Danto first saw Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes, it shook him to the core. He realized that although they were indistinguishable from ordinary Brillo boxes, they were now deemed to be art, because the tastemakers and consumers of art now understood the work through a certain theory of art. (He called this the “artworld.”)

There is a subsequent anecdote about Danto that I recall, that develops this idea, though I can’t find it anywhere now (perhaps it was some other art critic or perhaps I’d made it up). It goes: one day, Danto was milling around a gas station, and came across rubbish: some colorful strewn wrappers, some plastic bottles, your usual suburban detritus. It struck him then that even intentionality was not a necessary condition for art. Even without the artist, under the right lighting and mood, this too was art. This realization gave him great joy, for it had brought him to the true end of art. Eventually, Danto proclaimed “the end of art.” At its end, art had become all theory, “having finally become vaporized in a dazzle of pure thought about itself, and remaining as it were, solely as the object of its own theoretical consciousness.”

I had a similar moment of revelation, and it was this revelation that culminated in Anything but Human: that the end point, what Aristotle might have called the “final cause,” of our existence is rubbish. (I suppose Americans say “trash.”) This is increasingly true in a literal, ecological sense, of course: we can’t seem to stop generating rubbish, and we can’t seem to rid the world of it. But it’s also true in other senses: disinformation, fake news factories, clickbait, content farms on YouTube that claim that one can make a white strawberry by bleaching a regular strawberry, hot takes, trolls, memes. This is our final form; we are the ultimate instantiation of the second law of thermodynamics. To respond to a point in the question—we present ourselves as fastidiously disinfected, but in another sense, we are totally festering and stinking. (To quote William Carlos Williams, “the pure products of America / go crazy.”)

There is certainly much to lament, castigate, and rue—plenty of reasons to indulge in “candid jeremiads that drizzle from lips.” But also much to revel in and celebrate, this disgusting beauty we’re all mired in. In one of my poems in the book, I speak of not brushing my teeth to let the wretchedness sink in. So come, Let It. Sink In.

GB: I’m wondering why you’re drawn to copular verbs, which you use unapologetically and, in my opinion, quite effectively. You also use passive voice very well. Does either of these grammatical choices reflect core preoccupations of your book?

DLWJ: On the passive voice, I think it reflects the contemporary mood all too well. Humanity is at the absolute mercy of these superstructures—these huge obscene golden calves—we’ve set up above us, and we’ve totally lost control of them. Things are constantly being done to us, and we’re often powerless to change them.

On copular verbs, I guess I am always trying to make sense of the state of things, and the mood or sign they reside under—including myself. And that is indeed the chief preoccupation of the book.

GB: Could you talk about how and why the Isaac Watts hymn “Our God, Our Help” wove its way into “Anything but Human”?

DLWJ: I should first remark on how bizarre it is that we’re having this conversation at all.

That we are having this conversation in English. That I, a person of Chinese ethnic origin, a descendant of fairly recent immigrants to an island four times smaller than Rhode Island, located just off the Malay Peninsula, am talking to an American living in Texas about a Christian hymn written by an Englishman four hundred years ago.

Yet when I first met you, Greg, and spoke to you about the haunting strangeness of some hymns that I grew up singing, you recognized what I was talking about instantly. A hymn like “Our God, Our Help” could have been sung during the Monday morning chapel sessions at the Methodist mission school I went to; it could have been sung in Westminster Abbey; it could have been sung in a church in the American South.

What has stuck with me is this stanza:

Time, like an ever-rolling stream,

Bears all its sons away;

They fly forgotten, as a dream

Dies at the opening day.

It’s a spectacularly odd stanza, which seems to forget it is a Christian hymn and shifts from speaking about God’s eternal presence to simply describing the relentlessness of time—and our own insignificance. Particularly disturbing is the statement that we “fly forgotten, as a dream,” which “dies” at dawn—this is accentuated by the enjambment of “Dies.” (When singing, one also pauses before “Dies.”)

This is a classic memento mori, one might say, but it’s clear many contemporary congregations have found it too dispiriting—it’s left out of most renditions these days.

The hymn continued to echo in my head across the years, from the time I first sung it in school. Initially, I’d wanted to name the two sections of the book after phrases from the hymn, but that didn’t quite work out. Eventually, a sequence of prose poems came to bear the title “Fly Forgotten, as a Dream.” Appropriately, they’re dreamlike sequences full of dread. In their own way, these prose poems try to capture the haunting strangeness I spoke of. That sense of being a people whom our good Lord used to care about, but no longer.

GB: Speaking of your prose poems, one of them includes the following two sentences:

A crab crawls out of the boiling broth and becomes the Commissioner of Police. I fumble in my pockets for a knife and come up with a supermarket voucher from the nineties.

I wrote in my notes, “It’s as if Russell Edson or James Tate wrote the first sentence, intending to go full fantastical, but then, to my delight, Daryl took over and insisted on comical anticlimax to keep the poem in check.” What is it about the humorous letdown that attracts your imagination?

DLWJ: This is probably a reflection of my own personality. People who know me well will soon realize that although I appear outwardly serious, in good company (and with the right lubrication) I am always trying to find the irresistible punchline. More broadly, I try not to take myself too seriously. Time, like an ever-rolling stream, remember?

It is also, I think, a mirror of the contemporary condition. Things which once promised to change the world have become farces and punchlines—Facebook is perhaps the prime example. (The elevation of Zelenskyy to a wartime president-hero seems to be an all-too-rare example of this happening in the reverse.)

GB: One of your poems includes the sentence “New idiolects crystallise like jaggery on my tongue.” For me, one of the chief delights of this book is the way you mix all kinds of language together, including high-literary stuff, advertising lingo, bureaucratic verbiage, and street-corner slang. You bring out the strange lyricism in material that many poets would eschew or overlook. How would you describe the orientation toward language that enables you to see—and use—argots that rarely show up in poetry?

DLWJ: About that line—the original went something like “New idiolects crystallise jaggedly on my tongue.” But I replaced jaggedly with jaggery after recalling the traditional sugar (which doesn’t separate the molasses from the crystals, unlike ordinary sugar) used in the Indian Subcontinent and other parts of Asia and Africa. It was the perfect word: it was close enough to jagged to bring that association to mind to most readers; jaggery might be unfamiliar to many readers, reinforcing the impression of new idiolects; and well, jaggery is indeed a type of sugar.

The etymology of jaggery is fascinating. It comes to us via Portuguese, which took it from the Indian languages (see Malayalam, Kannada, and Hindi), and ultimately from the Sanskrit śarkarā. “All right,” you might say, “that’s . . . interesting, I guess.” But what’s cool is that sugar also comes from the same Sanskrit word, by way of Arabic, Persian, and Latin. The English language’s famed greed for words is so large that it borrows the same word—twice. (These occurrences are called doublets. There are also some triplets: cattle, chattel, and capital all derive from Latin capitalis.)

As you can see, I am madly in love with language and linguistics. What’s quite wonderful and bewildering is how the English language has evolved not just in different countries, but also in different contexts. I love moments when a copywriter overreaches, and staid copy becomes something else altogether. A found poem which I eventually excised from Anything but Human was cannibalized from a glossy prospectus of a new condominium development. (I append it at the end of the interview, in case it’s of interest . . . What’s crazier is that I live in that very condominium now.) The anthology of literary food writing I put together, titled Food Republic: A Singapore Literary Banquet, was inspired by a conversation I had with a fellow poet (who eventually became one of the co-editors) about some over-the-top Facebook ad a sushi restaurant posted. (We eventually convinced the restaurant to let us feature that piece of copy in the book.)

It is my belief that the energies for new, exciting poetry will not come from the all-too-rampant crop of pieties, nostrums, and orthodoxies masquerading as art. It will come from weird and eclectic idiolects, the borderlands of English, the non-native speakers. On the last point—some of the most exciting English poetry I’ve read comes from people who probably didn’t grow up speaking English: ko ko thett, Nicholas Wong, Wong May. (I should say that I consider myself very much a native speaker, so I am at a definite disadvantage.) It is that ability to break rules, to see beyond the rickety cage that is grammar, that is so vital for poetry. After all, Nabokov?

GB: How has your nonliterary professional experience influenced your poetic voice (if at all)?

DLWJ: I’ve worked in the civil service in Singapore for seven years now, in various posts. Over-the-top bureaucratic language is often hilarious, and I’ve found myself sneakily incorporating bits of language I’ve encountered in my work into my poetry. Perhaps there is also something inherently futile or farcical about bureaucracy in general, as the classic BBC series Yes, Minister so brilliantly demonstrates, and I wonder if that’s found its way into my writing too.

GB: Singapore seems to have a rich and lively poetry scene. Who are some contemporary Singapore poets you’d recommend to our readers?

DLWJ: It’d be a pleasure to do so. I should say our literary history in English doesn’t extend very far back—serious writing of poetry in English really only started in earnest after the Second World War. From the earlier generation of Singapore poets, I would recommend Arthur Yap, Wong Phui Nam, and Wong May.

If you’ll indulge me, I’ll speak a little bit about them:

• Arthur Yap’s poetry is observant, wry, and suffused with a knowing quietude. In some poems, he plays with language to push readers to the limits of their world, and beyond. In others, he quietly laments losses and weighs the passage of time. Above all, Arthur’s works have a painterly quality, where the words are akin to colors. He skillfully paints a serene landscape that seems still, but is teeming with life and tension beneath the surface.

• Wong May has Singaporean roots, though she now resides in Ireland, and she recently won the prestigious Windham-Campbell prize. Her poetry is one of intense mood and striking images (“The lake is a rabbit shot in the back”), one caught up in the violent and radical potentialities of the moment, or even of mundane, everyday objects.

• Wong Phui Nam is Malaysian by citizenship, but our two countries have had a long, intertwined history, including our literary histories. His poetry is dark, meditative, and apprehensive of death, and intensely moody too, in its own way. His interpretation of the Symbolists, his adaptation of symbols and Egyptian myths to a local context, and his inventive use of language were very influential on me, and my poem “The Prophet’s Day Out” is dedicated to him.

After that generation, some poets I really like are Yeow Kai Chai, Koh Jee Leong, Tse Hao Guang, and Hamid Roslan. Kai Chai’s work has been a particular inspiration. He is one of Singapore’s foremost experimental poets, and he has managed to carve out a mysterious, wonderful space of his own, inventing poetic forms like the twin cinema, and bringing a filmic quality to his poetry. His poetry makes you question the ground you stand on. It is at times gentle, at times acerbic, and at times absolutely searing in its potent, heady mix of allusions and dense images. He is a poet’s poet, perhaps, and reading his poetry enables me to free myself of the constraints of ordinary language and logic.

Among the younger poets who don’t yet have a full collection out, I am excited by the work of Shawn Hoo, Ruth Tang, Annabel Tan, and Jack Xi. Jack’s work I really am quite stirred by—it’s unbridled, surreal, imagistic, tragic, and funny.

GB: Thanks so much for that wonderful set of recommendations! And thank you for taking the time to talk with Southwest Review.

Greg Brownderville is the creator of the multimedia series Fire Bones (www.firebones.org) and the author of three books of poetry: A Horse with Holes in It, Gust, and Deep Down in the Delta. He also edits Southwest Review.

More Interviews