Held Hostage by Truth | A Conversation with Joe Koch

Interviews

By Andy Davidson

Horror is ascendant.

Have you heard? There’s revolution in the streets. New literary voices are being crowned in the genre with a righteous fury. Writers like Eric LaRocca, Hailey Piper, Gabino Iglesias, Gus Moreno, and Stephen Graham Jones are leading a blood-drenched charge on behalf of the lost, the broken, the misnamed. The final girls and the rotting corpses and the fallen saints. Their work is unsettling, poignant. Their stories reveal dystopian worlds of social decay and urgent need, of triumph and terror. Theirs is a celebration of what it means to be human: to feel, to want, to love without judgment or caveat. To be loved, in return—or to reject it all.

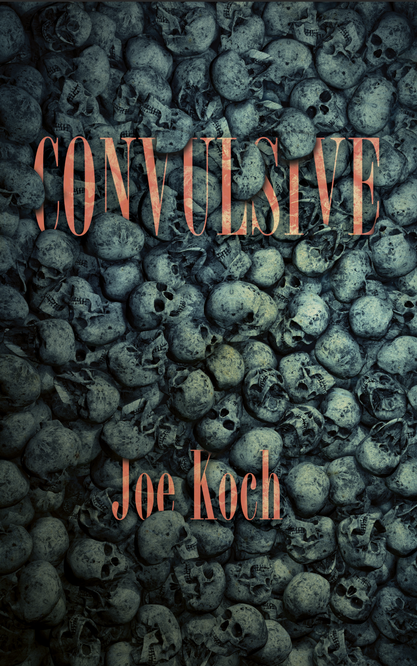

Among these original voices is Joe Koch, a writer whose stories are intensely challenging and rich beyond measure. Joe’s narratives take their cues from surrealism and nightmares. They also take a stand: no more of the old ways, the old points of view. No more baselines of normalcy. To read Convulsive (Apocalypse Party) is to experience a transformation of mind, body, and spirit in fifteen stages. With each story, you come closer and closer to being reborn, until at last you emerge damp and staggering from the pages, wholly not what you were.

I white-knuckled Convulsive in one sitting on a Sunday afternoon, with a notebook open beside me to jot down questions for Joe. But I couldn’t let go of the pages long enough to snatch up a pen. Later, when the questions came, my first thought was this: Horror can save us.

Andy Davidson: Thanks so much for talking with me about Convulsive, Joe. It’s no exaggeration to say it was a reading experience like no other. Before we talk specifics, I want to open with a big question. Why horror?

Joe Koch: The short answer is because horror breaks all the rules. Horror shows us characters and phenomena that break the rules of society, politeness, religion, science, sexuality, and so on; it’s the genre of transgression.

The longer answer is that I came to writing later in life than most authors. My background is in visual arts and counseling, and for the first couple of years I didn’t even realize I was writing horror. I followed my obsessions, things that haunted or delighted me, ideas and experiences I had passion for that I didn’t feel I could talk about with anyone I knew at the time. After acceptances for my first two attempts at writing (what ridiculous luck!), I grew frustrated with rejections from lit mags. I sought out reader feedback and studied work by those who are considered great authors. In the midst of this self-imposed course of study, I needed a break one day. Honestly, I kind of gave up. Since horror was my idea of fun, I dug out a book of horror stories from my then spouse’s bookshelves for relief. The first story was “The Museum of Dr. Moses” by Joyce Carol Oates. I knew her work, but I’d never thought of it as horror before reading that anthology. I realized horror isn’t about how classy or trashy the work is. It’s about how courageous a writer can be in examining what people normally turn away from—how fearless a writer can be in shining a light on what we hide from deep within ourselves. I knew I wanted to tell that sort of fierce truth.

AD: Who are some of your influences?

JK: My greatest writing influence is the garden I created and tended for about ten years when I lived in Michigan. More than any media I’ve enjoyed, the garden really taught me about writing. Cultivating organic food and native habitats requires attentiveness, patience, an editor’s eye for weeds and pruning, a loving acceptance of failure and success, and acclimation to the rhythms of an ecosystem you may influence but never fully control. Someday I should write more extensively about how the garden taught me to write! Even though the inspirations I take from art, music, film, and literature are interesting, they aren’t really teachers in the same way as plants. They aren’t practice. The creative process is an energetic act, and I’m the kind of person who learns by doing, not by watching.

AD: Almost all of the stories in Convulsive contain elements of body horror. Clearly, you’re working in that tradition, but you’re also a surrealist. Laird Barron says you write with a “poetic fury.” Some of your work puts in me in mind of certain fin de siècle writers like Baudelaire and Rimbaud. Can you talk a little about how these schools and modes hold hands in your work?

JK: Is body horror a tradition yet? I feel like it’s a very modern subgenre, and that it often ties in with concerns about bodily autonomy best expressed by the marginalized and oppressed who face routine threats to their basic human rights.

AD: Absolutely. I was thinking “tradition” in the sense of adding to the tradition of, as in you’re joining already established voices in that subgenre? If that makes sense? It feels like body horror is having a real moment right now, with Eric LaRocca’s works burning up the charts. And the travesty of Roe v. Wade being struck down . . .

JK: Yes, and that’s the sort of real-world horror that drives me to write. Sure, I have an ego, but what keeps me going beyond my personal need for attention as an artist is the importance of standing up and voicing dissent. I suppose I associate the fin de siècle with creative dissent and with queer culture of the past, and there’s no question my work is queer. It’s also arguable that body horror is inherently queer.

AD: Can you say more about that?

JK: I guess I mean body horror suggests a plasticity that can be painful, revelatory, transformative, and even erotic depending on how the subject responds. I’m just talking off the cuff here. I’m sure some queer theorists have written papers on this sort of thing, but when I was in school we’d barely started with feminist discourse! I’ll also admit to you I’m mostly familiar with Baudelaire and Rimbaud from listening to Diamanda Galas’ “Plague Masque,” so my lack of literary education is showing here, too. It’s OK, because admitting I don’t know the answers means there’s more to learn, and that’s exciting to me.

As far as aesthetic traditions go, surrealist painters and poets certainly inform my methods: Ernst, Arp, Breton. Behind the scenes of a story’s plot or theme, I’m often playing a little surrealist game for my own amusement with random words, phrases, or content. I’ve pulled moods, themes, and even a few characters directly from dreams. I’m tremendously interested in altered states of consciousness and have practiced different forms of meditation at one time or another, so I’m able to draw upon those former disciplines. Inasmuch as surrealism explores and exploits the subconscious, it allows—perhaps demands—subversion of physical norms. A more astute critic than me could dig into this intriguing intersection of surrealism and body horror that you bring up.

AD: There’s a passage in “Aristotle’s Lantern” that goes: “The viewer feels disoriented, a kidnap victim . . . If they don’t walk out in rage, they accept their passive stance and let the violence wash over them.” The deeper I got into Convulsive, the more I thought about those lines, substituting “reader” for “viewer.” Mainly because, at times, I felt disoriented myself, or held hostage to the horrible events unfolding. Do you think much about your audience as you’re writing? Who are you writing to? And is being a reader, by its very nature, a complicit act?

JK: A perfect segue from surrealism! “Aristotle’s Lantern” arose directly from a nightmare about drowning. That’s why it uses deliberately illogical language: to transmit the disorienting feeling of an inescapable bad dream. I guess it worked! I’d apologize for holding you “hostage” if this wasn’t the obvious intent of the story and the exact type of fearlessness in telling the truth that I mentioned earlier.

AD: I was delighted to be a hostage.

JK: That’s a phrase you don’t hear every day, and I’m delighted the story worked for you. I do think and care about the reader when I write. I think about how much I’m asking them to take on and whether I choose to hold their hand or not from sentence to sentence. Sometimes I let go and let them drown. I’m aiming for the reader to have an experience, not to just sit back and get comfy with a book. I think about the hundreds of stories people told me as a counselor that were denied, buried, and suppressed by their families, partners, teachers, and even by the professional advocates they placed their trust in because the truth was too ugly for them to hear. Too often, we place the burden of communication on victims who have been stripped of the means of communication. We blame oppression on the oppressed. So, in “Aristotle’s Lantern,” I wanted us to think about how we participate in a society where a kid being sex-trafficked doesn’t feel safe talking to a cop.

Reading is more about generosity than complicity. It’s like listening. We don’t have to judge or make a decision about what we read right away. We don’t have to agree with what’s on the page to engage with a piece of fiction. That’s the whole point of fiction—it can even operate by offending or distancing the reader. Fiction is as vast as the human mind, and I think the whole point of reading is to participate in that vastness.

AD: Horror has been described as the only genre that’s also an emotion. But it’s not just one emotion, right? There are so many shades of horror—despair, disquiet, disgust. Do you ever set out to hit one specific note in your work? Most of the stories in Convulsive run the gamut.

JK: Keeping with your musical comparison, many of my stories go for an emotional and textual “wall of sound” effect rather than trying to hit on that one good hook you want from a pop song. If I were a better businessperson, I’d spread out my ideas more thinly and make more money. I’ve thought more than once that I’ve put enough into a few thousand words to fill a novel. But then I come back to the purpose of the piece. Compressing all those ideas and emotions is like preparing a little psychic explosive. Some stories need to explode.

In longer works, especially my novella “The Wingspan of Severed Hands,” I’ve aimed to achieve a more focused effect. “Wingspan” contains sections of heavy prose, but at the heart of the story is a very simple idea. In some of my recent and forthcoming stories, such as “The Bleeding Tree” and “Schrödinger’s Head,” I’ve honed the style to a sharper point. I’ve taken that lush, grotesque prose about as far as I want to for the moment. Limiting tone is a new experiment for me.

AD: My favorite moment in Convulsive occurs in “Offerings.” It’s when that doorbell rings, and Blaine looks out her door, and starts to notice the bizarre Halloween masks the children are wearing. It creeps me out, in part, because it’s rooted in something harmless—trick-or-treating. So many horror stories work this way, juxtaposing the familiar with the unsettling or the weird. Do you consciously approach a scene this way? How does your imagination work when it comes to creeping out a reader?

JK: “Offerings” seems to be quite a crowdpleaser. I’m so glad you enjoyed it. Yes, sometimes I deliberately orient a story in the prosaic for the sake of grounding the reader before destroying their expectations and letting all hell break loose. For instance, I like to let the reader know what job a character does or if they’re hungry or houseless. Little things like that cement everyday existence.

But this idea of the normal and familiar is a class and race issue, too. Blaine could easily be imagined as Black or gay or both. In my mind, she’s definitely gay. But, because I needed to show her becoming “othered” over the course of the story, I omitted any suggestion of her being gay in the final draft. I often wonder if any readers have noticed she was closeted, both in the text and by the text.

Readers tend to make certain assumptions unless told otherwise: that a character is white, middle-class, cisgendered, and heterosexual. If I shift the baseline of “normality,” I have to shift the horror away from the (admit it: comforting) juxtaposition and go deeper into the human. Or inhuman. Horror set in the familiar affirms the familiar.

AD: Or disproves it? Strips its validity?

JK: I disagree. I’m tired of stories that don’t question the familiar right out of the gate. We need a new baseline that includes a wider range of what we consider “normal.” It’s a challenge to start a story from an unfamiliar baseline and escalate things from there; it’s a fun exercise as a writer, but more importantly, it’s a political act. It’s about shifting the status quo. So I’ll often start with a queer, homeless, or otherwise disenfranchised character and employ language that reflects their internal reality. For instance, I’ll shift pronouns or misuse words. Maybe it limits the popular appeal of my writing. But it’s a calculated risk I’m willing to take.

AD: I don’t know if it limits you at all. Right now seems to be the moment for bold voices making bold moves in the genre. I’m someone who strives for popular appeal in my work, and I once had a little old lady at a book club accuse me of being deranged because I wrote something about a woman eating a baby. Has anything like that ever happened to you? Do you think it’s possible to go too far? Or, as horror writers, should we go the farthest? (Maybe I’m thinking of “Rust Belt Requiescat.”)

JK: That’s interesting. No one has accused me of derangement yet, even though I intentionally depict intense states of madness, delusion, perversion, and intoxication. I’m so sorry that happened to you. I don’t think she understood the assignment!

AD: It was a revelatory moment for me. Some readers are unwilling to be made uncomfortable, whatever the reason. The way it happened amused me, but ultimately I also feel sorry for readers who find themselves in that woman’s position. They’re missing out.

JK: They are! Bringing too much judgment and a bunch of rigid preconceptions to art defeats the purpose, doesn’t it? It puts up a wall. I’ve run into some weirdly personal critique with visual art I’ve exhibited; specifically, some unwanted and incorrect psychoanalysis from a stranger trying to impress his date. It felt hurtful, mostly because it was dismissive of the work’s quality and relegated my art to a mere symptom. So far, with my writing, the further I go, the more people love it. It’s very freeing.

To answer your last question: yes, horror writers should go too far. We’ve made a deal with the reader to go the farthest of any genre and we should strive to uphold our end of the bargain.

I’ll add there’s a responsibility we take on when we explore extremes. Think of it like handling dangerous chemicals. People can get hurt. We need to use extra care. I try to be truthful to my experience of being human even in the most lascivious descriptions. I try to pay attention to what part of my psyche the text serves. There’s a sick feeling I get when something comes from a place of hate. I’ve trunked a few stories for it, but “Rust Belt” isn’t one of them. It’s weird to say that story comes from a place of love, but it does. It comes from a ton of historical research (again: I should have written a novel!) and a sincere struggle to wrap my head around evil.

AD: Your prose is incredible. It moves so nimbly from dreamlike and lyrical to crystal clear and precise, images so sharp they cut. “Her silence is ship’s brass.” How the hell do you do that?

JK: Thank you. You’re too kind. I’m always a little blown away by praise because I’m just doing my best and fumbling through like any other writer. I often write slowly and think about every phrase or character action and its ramifications for a long time. But I also go on fast tirades sometimes, too. I do lots of editing to manipulate the final draft, and yet I’m cavalier or foolish enough to leave chunks of my most impulsive ramblings in stories. I’d say I feel my way through stories more than I intellectualize; or, I do those things at different times. I’m ruthless about cutting out waste. If any sentence or point in a story sags with lack of emotion or lack of meaning, I tend to cut it out.

Of course, I’m a visual artist first, so I see a scene before I have words for it, or I have a feeling—a physical sort of sensation—about the shape or texture or tone of a story I want to explore. Following such an abstract lure means I’ll sometimes have no intellectual construct and certainly no outline. I love to go in blind. I’m nothing like the typical artist afraid of the blank page. I love an empty canvas. That’s the abyss, the positive void, and you get to dive in and do anything you want. What fun!

AD: Is horror a compassionate genre? Maybe in answering, you could talk a little bit about “The Anatomical Christ”?

JK: Yes, I’d say horror done right could be the most compassionate genre of all because it openly faces our pain and our failings. That’s what I meant when I said before you have to write with love. It’s about openness and compassion, and that means exposing yourself. You have to write with your whole stupid, naked, embarrassing self on the line. That’s how you get to the juicy stuff.

“The Anatomical Christ” is an exercise in compassion. The end of the story posits forgiveness as strength. Superficially, it’s a story written for The Big Book of Blasphemy, one that depicts Christ assaulting the protagonist and later performing as a sex worker. Oh, and the protagonist Aurora (named after the book by Michel Leiris) is a pregnant dancer who’s been shot. The story opens with Aurora trying to burn down a church. I imagine the setting as one of those chapels interspersed with strip clubs on Eight Mile Road near where I used to live outside Detroit. Anyway, having been reared evangelical, I’d held onto a lot of hate for Christ and Christianity. In this story, I tried to find things about Christ that I liked (or at least tolerated) because I wanted my blasphemy story to be soundly Christian.

AD: I grew up in a Southern Baptist church. I get that. Instinctively.

JK: It works its way into you, growing up like that. This story was a way of working it out; a dissection. I liked Christ awkwardly drawing in the sand when defending a prostitute; you know, just doodling like he didn’t know what to say. I liked him indecisive in the desert and in Gethsemane, like he’s playing Hamlet while the ghost of his father looms. I like those moments because the patriarchy is suspended.

About Christ, I started to think: This poor guy. He wants to do normal things and yet he’s got this big daddy telling him to make history and change history. So I let him come down off the cross and get in some trouble. He’s a mess, so he’s very sexy to me. He and Aurora meet and re-meet in this psychological space beyond the patriarchy where genders are interchangeable, too, so that was fun. What’s important to answering your question, though, is that, in the end, Aurora forgives him and embraces him. After she’s gone through an incredible amount of pain, she acknowledges his suffering and humanity.

AD: I loved this, how the story reclaimed compassion outside of that patriarchal framework. Which is weirdly faithful to the spirit of Christ. Compassion is for everybody.

JK: Thank you! Compassion toward self and others is the heart of Buddhism, too. Studying and practicing a little bit in that tradition brought me around to a better tolerance for Christianity and Christians. I don’t hate Christians. I’d just like them to stop using their religion as a tool of oppression and abuse. In no small part because it’s the opposite of the message of their own sacred text.

AD: Convulsive engages such a wide range of subject matter, from saints and martyrs to mythological creatures, from snuff films to demon children. What’s the throughline in this collection? How did you put it together?

JK: It came together intuitively when I looked back over my published work from the past few years. I had about fifty short stories out at the time and I reviewed them for three things: stories that meant the most to me personally because they held inspirations and images from people or life experiences from my past that were dear to me, stories that explored different stages in my own journey toward understanding gender and coming out; and literary merit.

The title Convulsive refers to a quote from Andre Breton: “Beauty must be convulsive, or not at all.” I wanted the stories in this collection to each be a creature that hatched out of its own strange chrysalis—to be expressive of a beauty that struggles into being despite the ugliness and oppressive forces of the world.

AD: Do you write a story in one sitting or over multiple sessions? Do you revise endlessly, like me?

JK: Writing is a lot like dreaming while you’re awake. The writer’s job is to bear witness and report back with care and honesty using whatever means they have on hand. My process changes from story to story.

AD: What’s next for you?

JK: Lots of short stories in the pipeline coming out over the next few months, about twelve I think. Stories of the Eye, an anthology I co-edited with Sam Richard, is due out from Weirdpunk Books later this year. I’m so impatient for its release. This was my first time editing an anthology, and it came from a concept I dreamed up and mentioned on Twitter with little hope of making it happen, and lucky for me Sam saw my tweet, got in touch, and said “Let’s do it!” The book explores relationships between artists and models in different facets of the arts through a horror lens. It includes original work by Gwendolyn Kiste, Hailey Piper, Gary J. Shipley, Donyae Coles, me, and others.

I’m talking—and this is just talk—with Paula Ashe about a project based on the French film Martyrs. It would be a book somewhat like the recent Children of the New Flesh: The Early Work and Pervasive Influence of David Cronenberg. Paula’s the author of We Are Here to Hurt Each Other, which I’m calling right now as the collection that will win the Stoker this year. She’s lectured on Martyrs and has the academic background I lack; my education is in art and psychotherapy, so we complement each other well, I think. As I said, we’re just talking now, but if a publisher is interested in hearing more about our idea, please get in touch!

Andy Davidson is the Bram Stoker Award-nominated author of In the Valley of the Sun, The Boatman’s Daughter, and The Hollow Kind. He holds an MFA from the University of Mississippi. Born and raised in Arkansas, he makes his home in Georgia with his wife, Crystal, and a bunch of cats.

More Interviews