I Wake Up Streaming: October 2020

Movies

In this special Halloween edition of “I Wake Up Streaming,” novelist William Boyle rounds up his top streaming picks for the month of October. The column’s name is a play on the 1941 film I Wake Up Screaming, starring Betty Grable, Victor Mature, and Carole Landis. While the film’s title hits a pleasing note of terror and despair, changing that one letter speaks to the joy of discovering new films and rediscovering old favorites, as well as the panic that comes with being overwhelmed by options.

When I was about eight, I watched The Exorcist at my cousin’s house. I don’t quite remember the circumstances, except that we were in his basement and the TV had a sort of looming antenna and his dog was barking. It messed me up. Bad. I walked out of that house a different person, older and afraid of everything. For a Catholic schoolkid already consumed by guilt and shame, it added this new element of existential dread. I saw demons everywhere. The world was full of demons waiting to inhabit me. Goodness, I figured, only masked evil.

Following that, my relationship with horror was complex. I’d been burned by it early, but—like so many fans of the genre—I couldn’t stay away. It was both punishment and catharsis, which made perfect sense to my Catholic imagination. Of course, it also helps that I grew up in the ’80s and ’90s when horror was cultural currency. I devoured books by Stephen King. You couldn’t really exist without some familiarity with the Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street franchises. I recognized Halloween as a masterpiece of tone and form and idolized John Carpenter. Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds shook me to my core—I’m still afraid of bird attacks and haunted by memories of pigeons that have swooped too low, hummingbirds that have darted too close, a raven that flew into a glass door like a portent of some coming apocalypse.

After my first viewing of A Nightmare on Elm Street, when I was ten, I didn’t sleep for a week. I finally figured out the cure. Each night, after I prayed, I’d lie there in bed and imagine a scenario in which Freddy Krueger was gunned down by Robocop. It became a ritual. It was stupid, but it worked, becoming the only way I could achieve the peaceful state needed to rest. This is what people always do, I later realized. Isn’t prayer itself the same sort of ritual? Isn’t organized religion, in some sense, the same as the horror genre? People find reassurance in acknowledging the presence of evil and seeing it cast out and defeated.

Of course, it doesn’t always go that way. Not in the movies and certainly not in real life. These days, fear itself is currency. The world has always had its tremendous horrors, but now we’re inundated with them in ways we never have been, assaulted constantly by threats of doom, death and tragedy spinning on a ticker tape before our pinned-open eyes. A global pandemic, impending climate disaster, fires and floods and storms, corruption and immorality of the highest order, humanity’s worst instincts threatening the very fragile order of things. At best, we can hope for old age, where our bodies and memories begin to fail us, where each day is fraught with peril. Ha. So, what purpose can horror serve in a world already so horror-filled? I think back to that kid that I was, yearning for both punishment and catharsis. I guess the same is still true. Horror takes hold. It lets us know we’re alive. If we’re afraid, we’re not dead yet. In its own way, that’s a form of hope.

For an October even more electric with tension than usual, here are some streaming horror picks to help you keep punching. Stay afraid. Stay alive.

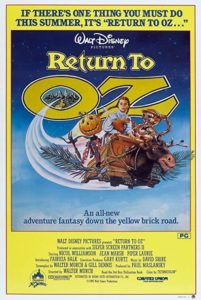

Return to Oz. 1985. Disney Plus.

I can’t lie. I’d like to say I saw this film as a kid and it destroyed me—it’d be a better story. But I didn’t see it until I was about twenty, a junior in college. I’d seen most of the movies meant to scare me and yet I’d somehow missed this. As a kid, I worked hard to avoid anything perceived as made for children. That’s how I wound up reading Jim Thompson by age eleven, how I wound up seeing Blue Velvet and Wild at Heart around the same time—I was drawn to anything that might be thought of as off-limits for a kid. By college, I had some catching up to do. I went back and read a ton of children’s literature, especially original folktales and fairytales. You want horror, go back and read those or revisit a book like Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio (beyond terrifying). In any case, through a recommendation from a friend, I wound up watching Return to Oz and reading L. Frank Baum’s entire series. I already loved The Wizard of Oz because it had blown me away as a child, and it continued to have an impact on me because it was such a big influence on David Lynch. My self-curated film education was rooted in horror, the surreal, and the absurd. I’d gone deep into a catalogue of exploitation movies and scummy foreign horror and sweat-slicked slashers and a million things meant to unnerve me or gross me out or do whatever. But nothing, absolutely nothing, had the impact of Return to Oz. Dorothy getting shock treatment. The Wheelers. Severed heads. Queen Mombi. The Nome King. It’s the kind of film that crawls in your subconscious and stays there, as only the best horror can. Of note: it’s the only directorial effort of Walter Murch, film and sound editor of classics like Apocalypse Now, The Godfather I-III, and The Conversation. Double feature recommendation: Nicolas Roeg’s The Witches (1990, Netflix), based on the Roald Dahl novel. I recently rewatched this with my six-year-old daughter (at her urging) and she freaked out; I felt simultaneously pleased and racked with guilt.

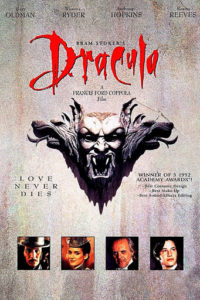

Bram Stoker’s Dracula. 1992. Shudder.

I was never as disappointed in a movie as I was by this in 1992. I was fourteen, deeply into movies. I read the novel in anticipation. I got some big glorious book that included pictures from the set and the full script. When I finally saw it, I didn’t hate it, but I felt let down. The truth is I wasn’t equipped to enjoy it. I wasn’t yet equipped to see it as an homage to the best horror of the ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s. My original viewing had been in a dying Brooklyn theater, and a subsequent viewing on VHS didn’t do much for me, but seeing it now—in 4K Ultra HD—man oh man, is it ever gorgeous. I’m not being hyperbolic when I say it’s one of the best-looking films ever made. Every frame truly a painting. The practical effects. The gore. The religious iconography. The Boschian vision of hell on earth. The bodies, both beautiful and tortured. Only someone who’d grown up in the Catholic church could make a vampire movie like this, all bombast and blood, shadows and sin. The film feels like a confession or at least an exorcism of some dark, deep desires. Oldman gives what is likely his best performance. And the supporting cast—Winona Ryder, Keanu Reeves, Tom Waits (as Renfield!), Anthony Hopkins, Sadie Frost, Cary Elwes, and Richard E. Grant—is perfect. Double feature recommendation: Carl Theodor Dreyer’s brilliant and visually striking Vampyr (1932, Criterion Channel and HBO Max).

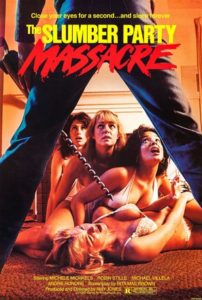

The Slumber Party Massacre. 1982. Criterion Channel, Shudder, Tubi.

Part of the Women Filmmakers of New World Pictures feature on the Criterion Channel, this was an early favorite for me. From a young age, I had a sort of moral code when it came to movies. I would give anything a shot, but if something made me feel rotten in the wrong way or felt truly ill-intentioned and gross, I would react strongly against it. This movie felt different. What I didn’t realize as a kid was that I wasn’t seeing the usual misogynistic, male gaze–centered slasher. Written and directed by Amy Holden Jones, this feminist slasher manages to feel both tender and terrifying. Amy Holden Jones got her start as an assistant on the set of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, where she met cinematographer Michael Chapman (RIP), whom she went on to marry. Chapman introduced her to Roger Corman, always willing to give talented young artists jobs (and at the vanguard of giving women gigs they were generally shut out of in mainstream Hollywood). Jones edited Hollywood Boulevard and Corvette Summer for him. After that, she had the opportunity to edit Steven Spielberg’s E.T. but turned it down when Corman offered her the chance to direct her own film. Thus, at age twenty-seven, she made her directorial debut with The Slumber Party Massacre, an economical, sharp-eyed, and smart standout of the slasher genre. Double feature recommendation: Deborah Brock’s wild follow-up, Slumber Party Massacre II (1987, Tubi), a miracle of pastel and blood.

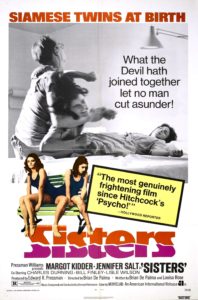

Sisters. 1972. Criterion Channel, Kanopy, HBO Max.

The ’70s Horror collection on Criterion is incredible; you can get a great education in horror there. I’ll stick to one choice pick: Brian De Palma’s Sisters. A longtime favorite of mine, it stars Margot Kidder, Jennifer Salt, and Charles Durning. It’s typical top-tier De Palma: subversive, self-aware, voyeuristic, stabby. Kidder is ethereal as twins, one good and one evil. De Palma’s playfulness, his shifting perspectives and use of split screens, makes it all a wonderful swirl of weirdness and tension. He makes nods to Vertigo, Psycho, and Rear Window, and features a Bernard Herrmann score, but the film never feels derivative of Hitchcock. He leaves us unsettled in a wholly original way, building from Hitchcock’s influence, and his dark sense of humor guides the picture’s conclusion to a place that doesn’t feel neat or predictable. De Palma shatters genre lines, blending horror, suspense, comedy, and surrealism. In many ways, to me, Sisters is about the possibilities of the genre. Double feature recommendation: John Grissmer’s Blood Rage (1987, Prime Video), an underrated twin-centered slasher.

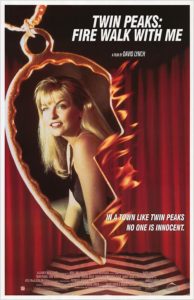

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. 1992. Criterion Channel.

David Lynch has committed more moments to film that have truly terrified me than anyone else. If I were doing one of those Bravo-style “Scariest Movie Moments” countdowns, my number one would no doubt be the dumpster scene in Mulholland Drive. (My top ten would also include two or three scenes from Twin Peaks: The Return.) While Lynch is a genre-bender, often utilizing elements of noir, horror, and even slapstick comedy, he’s never only one thing. Yet, for me, the most effective and affecting of all horror films is Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. A dissection of trauma. A nightmarish whirl of images and sounds. Is there a monster anywhere more sinister than BOB? Is there anything more frightening than the possibility that we all have our own BOBs waiting to take our bodies over? Lynch is the master of constructing scenes that burn themselves into your memory. I’ll never forget seeing this at age thirteen. As a huge fan of the show and Lynch’s other films, I knew what to expect, having been terrified pretty consistently by his work (particularly by BOB, Hopper’s Blue Velvet turn, and the stretch of Wild at Heart featuring Willem Dafoe). Still, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me was something different: it played like sheer horror, like the American subconscious come to life. The best horror changes the way you see and live in the world. That’s what this film did for me. Nothing was ever the same. It was like peering into someone’s dark dream. There was the world before this, in all its ordinariness, and the world after, pierced through with pain and mystical dread. Horror is ultimately about making sense of evil, and there’s no other work that concerns itself so fully with the nature and sources of evil. In a film full of haunting images, a scene that never fails to rattle me is The One-Armed Man pulling up in his car next to Leland and Laura, shouting. This might seem innocuous next to great gory murders and jump scares, but it sizzles with some kind of unfamiliar energy that burns and shrieks. Double feature recommendation: Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House (1977, Criterion Channel and HBO Max), which is inventive, wild, and has the same kind of experimental arthouse spirit as Lynch’s masterwork.

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, and City of Margins, and a story collection, Death Don’t Have No Mercy. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His writing on film has appeared in Oxford American and CrimeReads. He used to have a blog about ’70s crime films called Goodbye Like a Bullet. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

More Movies