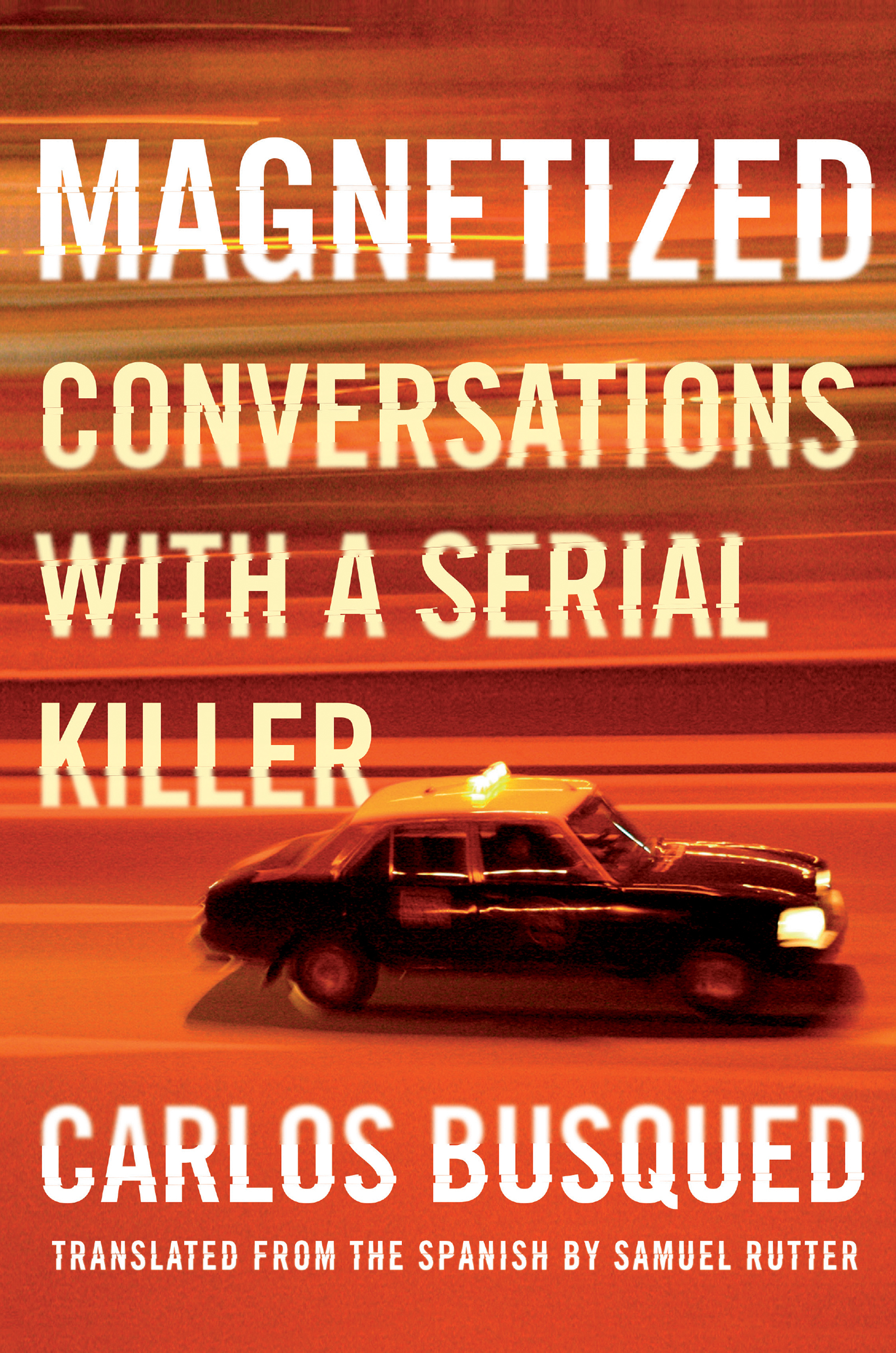

Magnetized: Conversations with a Serial Killer

Reviews

By Gabino Iglesias

Ricardo Melogno was a lost nineteen-year-old boy wandering around Buenos Aires on foot and living in the interstitial space between the reality around him and the “movies” that constantly played in his head. Inside him, something like hunger was driving him. He needed to kill. It was a feeling he had never had before; an overpowering drive that propelled him to get into a taxi something or someone told him was the chosen one, and then putting a .22 caliber bullet in the head of the taxi driver before sitting in the backseat for a while and smoking a cigarette. During that week in September of 1982, Melogno would go on to kill three more taxi drivers, each murder as cold, precise, and senseless as the first.

More than thirty years later, Argentine author Carlos Busqued, author of the Herralde Prize–nominated novel Under This Terrible Sun, started visiting Melogno in prison. Their conversations focused mostly on Melogno’s thoughts and memories from the time of the murders, but also touched on life in prison, the role his environment played in making him a serial killer, and religion. Luckily for Busqued, and for readers, Melogno is a smart man whose eloquence and willingness to talk and explore his own psyche translated into an absorbing and profoundly unsettling nonfiction book.

Magnetized is very well researched. Besides Melogno himself, Busqued drew on a plethora of sources that ranged from interviews with doctors and forensic reports to court documents and newspaper articles. However, the interviews with Melogno are at the core of the narrative, and they make for some engaging, eerie reading.

This book grabs readers for various reasons. The first is that Busqued is eager to know more, and he never judges Melogno. In fact, his short, focused questions are usually no longer than one or two lines of text, and they regularly lead to answers that fill up several pages. The second element at work here is the bizarre narrative Melogno constructs through his answers (with a bit of help from Busqued, who arranges them thematically to give the book a sense of cohesion and adds a great deal of clarity to Melogno’s story).

Melogno’s ability to revisit his past despite the three decades of incarceration that separate him from the killings is outstanding, and the clarity with which he speaks about the murders is chilling:

At one point, to talk about this, to sketch out the idea, I used the phrase, “If I felt like eating, I ate, if I felt like sleeping, I slept, and if I felt like killing, I killed.” A stupid thing to say that did me no favors in court. But when I talk about “feeling like it” I don’t mean it the way you might say “I feel like going to the theatre.” If you feel sleepy it’s not that you feel like sleeping: you actually start falling asleep. That’s how it is if you’re sitting down, lying down, standing up. You fall asleep, or you go into a daze. It’s not like you’re trying to fall asleep; sleep comes, no matter where you are. It was the same thing for me—it’s not like I felt like going out and killing people. It was something natural that happened to me, that flowed through me.

The thing that sets Melogno apart is that there was no motive for his crimes. He didn’t want money or vengeance. He didn’t hate taxi drivers or men in general. He didn’t even take pleasure in killing. Also, in the time he has been in prison he has been subjected to every possible psychological test, and no doctor has been able to give him a diagnosis that worked. In his life behind bars, Melogno has been diagnosed as: “Borderline, psychopath, psychotic, schizophrenic, autistic, paraphrenic,” and others. This lack of motive and failure to be diagnosed have led to continued life behind bars despite his having already completed his sentence:

The key issue, and my main problem in judicial terms, is the lack of motive for my crimes. If I had said that I killed in order to steal money, I would have been set free fifteen years ago. Or even if I said I did it for pleasure. At least there’d be a logic to it. But I don’t recall any reason or anything that set me off. There was no precedent.

Narratives with smart serial killers aren’t new, but Magnetized is special because Melogno is a shapeshifter who morphs into various versions of himself in the book’s 175 pages. He starts out as a killer, a confused youngster with an unknown mental illness. Then we learn about his mother’s spiritualism and the way that religion affected him. Later, he transforms into someone who no longer feels the need to kill and wants to help others explore why he did what he did. Nothing he says up to that point sounds sensational. However, toward the end of the book, he becomes a “maniac” in prison who has an altar in his cell, prays to Satan, and builds small voodoo dolls with paper and blood and then keeps them in tiny caskets. Surprisingly, he is self-aware through every phase, and even at the end he talks about his own motivations with shocking clarity. Here’s how he answers when Busqued asks him about his will to live after all he’s been through:

To make it out of all this shit around you, there’s always the possibility of killing yourself. On those sleepless nights, you say to yourself, “I’ll kill myself, and then all this bullshit goes away.” Sometimes you have to weigh things, and find something to outweigh the desire to die. In my case the counterweight was always hatred: I always thought that the day I killed myself the doctors would celebrate, saying, “Finally we got that son of a bitch to kill himself.” I’d hate to give them that pleasure, that victory.

Busqued is an astute storyteller and a talented listener. Melogno is a strange man with a dark past whose psyche has confused every professional who’s come in contact with him; a mellow individual who once spent a week shooting taxi drivers in the head, in each case going to a restaurant after to eat a nice dinner. Together, they make Magnetized a thought-provoking and unique true crime book that’s a must-read for fans of the genre and anyone with a passing interest in killers or the human mind.

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, professor, and book reviewer living in Austin, Texas. He is the author of Zero Saints and Coyote Songs and the editor of Both Sides: Stories from the Border. You can find him on Twitter @Gabino_Iglesias.

More Reviews