More Fun Down Here | A Conversation with Garth Miró

Interviews

By Mila Jaroniec

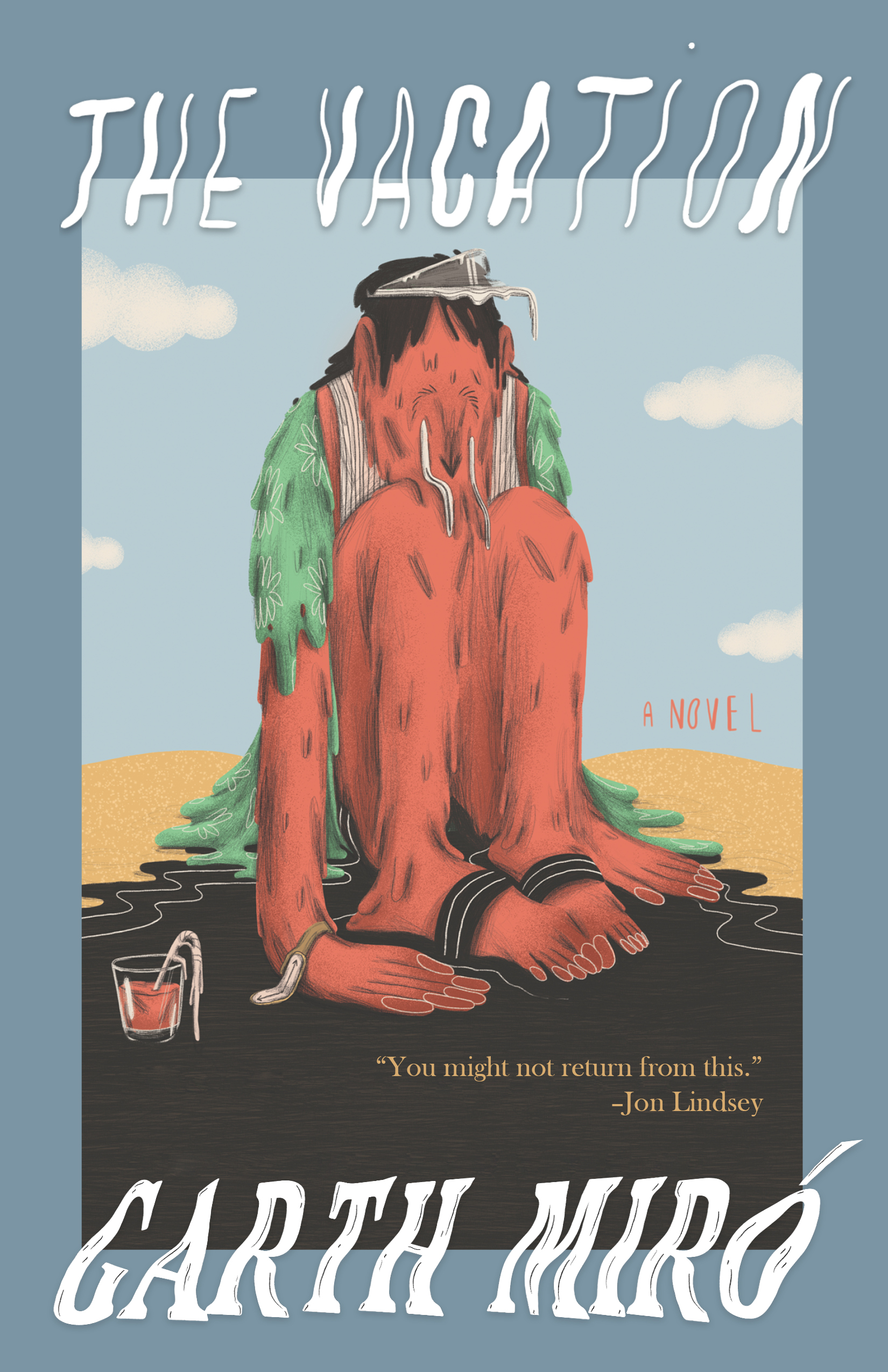

Garth Miró’s The Vacation is the perfect summer novel for those who prefer their beach reads a little sinister. Hugo, the reluctant protagonist, begrudgingly boards a cruise ship with his wife CC, an old-money type for whom he feels absolute contempt (and who quite possibly has been impregnated by another man), and her rakish brother Vincent, who always seems to have a scheme up his sleeve. As if that weren’t stressful enough, Hugo stopped using heroin only two weeks ago. To cope, he drinks. Not unlike the passengers who are so intent on all-inclusive consumption, there’s no distinction between Hugo’s nervous drinking and their pursuit of pleasure. The situation is uncomfortable, but manageable, until it becomes clear that this is no ordinary cruise line—and getting off is not a guarantee.

A little bit Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, a little bit Four Rooms, a little bit Pirates of the Caribbean, and a little bit Naked Lunch, The Vacation is a melty, paranoid nightmare that’s simultaneously outrageously funny, bitingly insightful, and patently horrifying. You’ll emerge grateful to have both feet planted on dry land.

Mila Jaroniec: In A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, David Foster Wallace writes: “I am now 33 years old, and it feels like much time has passed and is passing faster and faster every day. Day to day I have to make all sorts of choices about what is good and important and fun, and then I have to live with the forfeiture of all the other options those choices foreclose.” What is your method for making choices, in writing and in life? Do you ever feel paralyzed by choice in either arena, and if so, how do you exit the stalemate?

Garth Miró: I don’t really ever feel paralyzed because I don’t think all that much. DFW was a big overthinker, in my opinion. A lot of writers are overeducated, over-moralizing, and over-pathologizing. It makes them a bit boring. I don’t plan. I don’t even worry if things make sense. I find that writing (and life) works out better when I’m acting on feeling. Does it feel good? Then it’s good. And worrying about importance? I’m just a handyman. I don’t believe we get to decide what’s important; that reveals itself after the fact. Choosing beforehand is just pretending we’re in control. You can’t design anything, writing or otherwise, into importance—not truly. And that’s fine. I’d much rather be unimportant anyway. It’s much more fun down here: we’re shoplifting and getting in fights and waking up hungover, our days ahead only able to go up and get better.

MJ: That’s true. You can’t superimpose importance. But how do you know when you’ve achieved what you’ve set out to do?

GM: Honestly, when I can’t stand looking at it anymore. There’s a point when things start to click and the story takes on its own life. You’ll get this feeling it wants you to let it go, so it can walk out into the world and become whatever it’s going to become.

MJ: Cruises are creepy enough without any additional fictionalization, as both the title essay in DFW’s collection and your novel suggest. Did you go on a cruise for research purposes or pick an equally chilling all-inclusive experience from which to observe bottomless pleasure-seeking? While writing this book, what did you learn about people (as individuals, as a group) that you hadn’t grasped before?

GM: I’ve been on two cruises. Both were creepy. They were great. It’s the perfect place to indulge because it’s like an agreed-upon separate reality, away from land, from real life, an impermanent space. Like a box that self-destructs and erases all memory of itself. There’s something very perverse about a cruise ship that I like. You’re trapped with all this cheap excess; you have to face off against it and see how you would be if you were born one of those prized pet poodles, or a child god from ancient Anyang China. But it’s a kitschy, discount version of that. Our culture is obsessed with achievement. We go crazy if we don’t think we’re getting something done—more importantly, something that makes us money. People waste so much of their lives thinking about making use of their time. I think we should value laziness more. The stoics believed leisure to be the absolute condition of human accomplishment.

MJ: The Vacation is one of those rare books whose specifics—plot, characterization, all grounding elements—somewhat infringed on my reading experience. Most of the time, I need something to hang my hat on, but not here. I didn’t want to think about Hugo’s forthcoming baby and his whispering heroin addiction because then I subconsciously kept trying to place him as a human being with an identity. But the narrative doesn’t support that. The inside of Hugo’s head was the most compelling place to be. What other books do you know that do that—suspend narratives in midair, where any attempt at anchoring can only grasp at the ankles of something meant to ascend?

GM: I think we see things differently when it comes to this stuff. I believe the plot and characterizations are needed in this book. There’s nothing that bores me more than an author taking readers hostage on an endless meandering of ruminations. It’s like they believe plot will sully their brilliant little trinkets. Their ideas are too precious. We must swallow them raw and pure and without distraction! In order to propel my ideas forward, so they have something to bounce off of, I think plot is needed. It shows how the ideas could potentially interact with the (or a) world. Otherwise, the ideas start to eat themselves.

As far as characterization goes: Hugo is a cartoon, sure, but I’m not going to start lopping things off because he’s a gross cartoon. I personally think that’s relatable. Who doesn’t sometimes get completely fed up with life, finding out everything they’ve been taught might be a lie, so they just throw up their hands and decide to become a bit of a villain? In The Vacation I tried to push that to an extreme—mostly for comedic purposes. I think it’s cathartic to fantasize about cutting your boss’s head off. You’ve never done that? If you haven’t, you should try it. And again, I don’t know if I want to write a book that’s trying to ascend. I’d rather stay down in the muck. The muck is more interesting.

MJ: That’s a great example of the contrast between authorial intent and reader reception. I’m always surprised when readers tell me I’m doing things in my work that I never intended to do, but that’s part of the magic, isn’t it? Accidental resonance. But: ascension. Can that be accidental too?

GM: Sure. But you’re right, I think that happens more in the reader’s mind. Some people see certain things based on who they are; certain things will stand out to them, mean something you possibly never intended. Like that picture of the old woman that looks like a young girl to different people.

MJ: Publishing with an indie press is uniquely great because of the amount of creative control you get to retain, especially if you’re a debut author. A good editor/publisher will bring the book closer to its true form. What did you find in Expat Press that you wouldn’t have found anywhere else?

GM: You said it. Expat let me do whatever I wanted. They let me choose Sam Pink as an editor. They let me hire my wife and friend to do the cover. I think larger publishers basically tell you how things are going to go. They’re businesses. But, in the future, if one of them wants to give me a bunch of that business money to do what I want, well, I’d be fine with that.

MJ: If you knew you were going to die one year from today, how would you spend the year? Is that different than how you would spend a year-long vacation?

GM: No, not really. I think the goal is to make the vacation unneeded. You shouldn’t want to take a break from your life. You should live how you want; you still die if you don’t. I’m working on it. I always feel like I’m going to die soon.

MJ: How do you personally distinguish good and bad writing? If you were in charge of the literary canon, what changes would you make?

GM: “Good” writing makes me furious that I didn’t write it. “Bad” makes me happy I didn’t. And being in charge of the literary canon would be a job I’d have to pass on. Maybe I’d add Story of the Eye—is that already in there?

MJ: Do you have any advice? Not for writing or publishing necessarily, just in general.

GM: Don’t do heroin.

MJ: Three words to describe your novel-in-progress?

GM: Humiliating, exorcising, trashy.

Mila Jaroniec is the author of two novels, including Plastic Vodka Bottle Sleepover (Split Lip Press). Her work has appeared in Playgirl, Playboy, Joyland, Ninth Letter, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, PANK, Hobart, The Millions, NYLON and Teen Vogue, among others. She earned her MFA from The New School and teaches writing at Catapult.

More Interviews