Show Me Your Shelves | Michael Farris Smith

Interviews

Show Me Your Shelves is a regular book column by Gabino Iglesias. In this edition he talks with Michael Farris Smith, author of several novels, including The Fighter and most recently Blackwood.

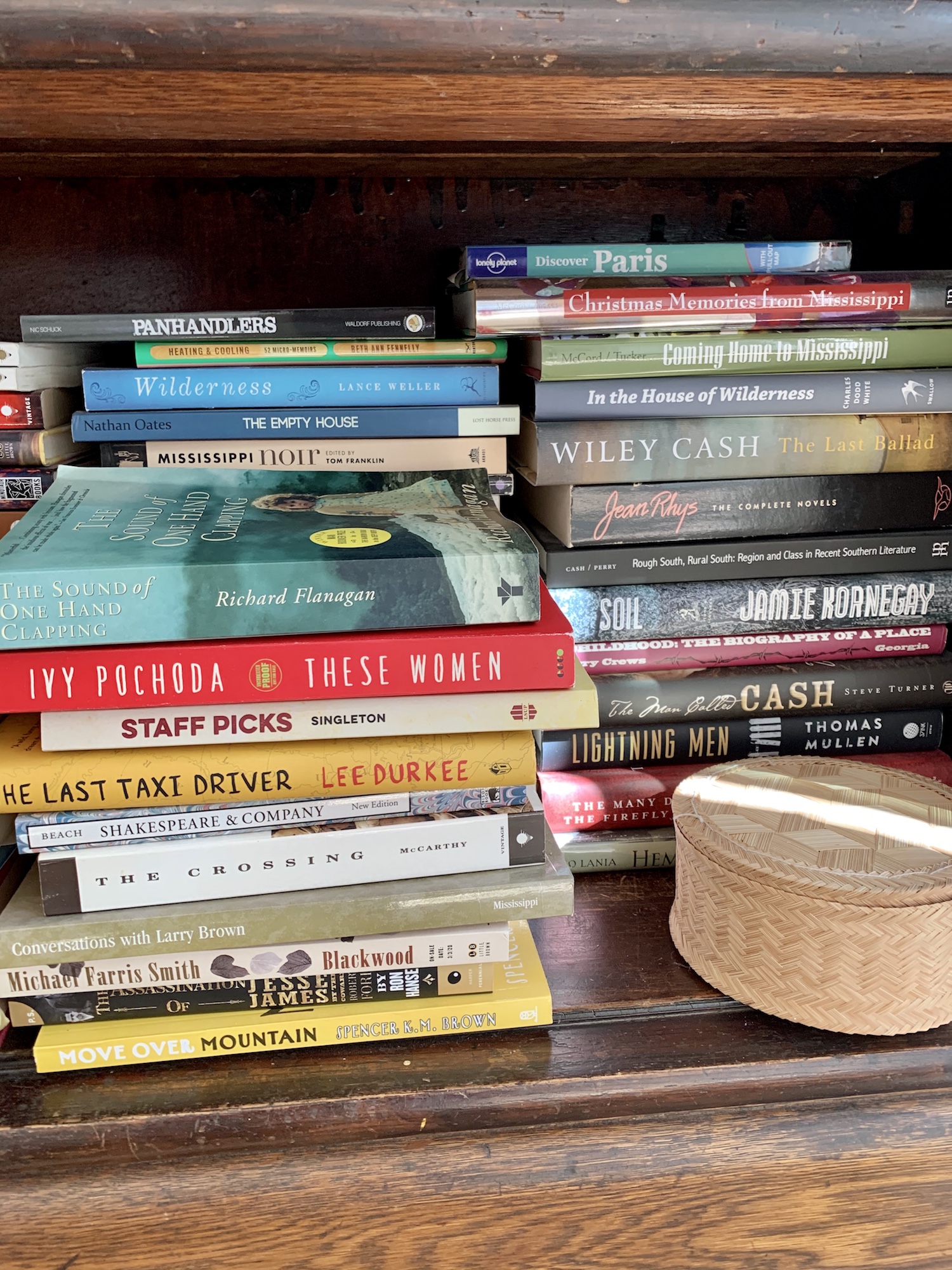

As a fiction lover and professional book reviewer, I talk to people about Michael Farris Smith’s work because the man is one of the best storytellers out there. His prose is both lean and poetic, his narratives gut-wrenching and darker than most alleys at midnight. However, when I’m talking to friends, I usually tell them about meeting Smith in a little bar in Oxford, Mississippi while I was in town for a panel at the Oxford Conference for the Book in 2019. You see, I’ve always heard you shouldn’t meet your heroes, so I always expect great writers to be awful people whenever I sit down with one of them in real life. Smith wasn’t awful; he was smart, eloquent, and funny. We talked about writing, publishing, history, Faulkner, and teaching. Then it was over and I drove home. Almost a year later, I received a review copy of Smith’s latest novel, Blackwood, and that night in the little bar came back to me. The affable man I’d shared beers and jokes with was back, but now he was doing the same thing he’d been doing before I met him in real life: telling me an outstanding story, a narrative that was bleak and beautiful, violent and soulful, gritty and strange. Yeah, Blackwood might just be Smith’s best novel so far, and that’s like saying it’s Mike Tyson’s hardest knockout. Once I finished the book, I started wondering what books filled Smith’s shelves. It was one of those questions I never got around to in that dark bar. Well, here we are. Smith agreed to talk books and writing with me once again, and this time I got him to show all of us the tomes sitting on his shelves.

Gabino Iglesias: Who are you and what role do books play in your life?

Michael Farris Smith: Damn. You don’t believe in easing into this, do you? Who am I? Well . . . I guess it depends on what time of day or night it is. Sometimes I’m daddy. Sometimes I’m the guy riding with the windows down and something cold in the cooler. Sometimes I’m an artist who can’t sleep at night, filled with the images of what I see and what I want to portray on the page. Sometimes I’m the beginner full of doubt. Sometimes I’m so sick of everything that I see and hear that I want to find a cave somewhere and disappear inside, and sometimes I’m so filled with everything that I see and hear that I want to wrap my arms around the world and squeeze. Mostly, I’m trying to figure out who I am and I don’t really want to come to any kind of conclusion because that means the evolution is over.

What role do books play in my life? Going back, books saved it. I was lost for a decade. No idea what to do or which direction I was going. Then I started reading, and something began to change in me. I started to feel this pull toward . . . something. And then finally, I was so consumed by what stories and novels did to me and my imagination that I had to figure out if I could do it myself. Books gave me a passion I never had before.

GI: The publishing world talks a lot about Southern noir, Southern fiction, whatever. Folks like you, Joe Lansdale, and William Boyle, to name a few favorites of mine, all live in the South and write about it, but your work has nothing to do with the work of the others. Why do we keep using that term? What does it mean to you, if anything?

MFS: I go back and forth on this. It feels like a category I aspired to be in because so many of my favorites live there. But now that I’m there, sometimes I think the categorizing of Southern fiction or Southern noir is unfair. I mean, yeah, it’s Southern fiction or Southern noir. But does that make it any less human? Any less universal in theme or emotion? I would argue it makes the work more human because of the heart and soul left on the page in Southern fiction. [The label] sometimes gives it a regional connotation when it’s universal. At the end of the day, everything is regional. The story has to be set somewhere. The writer has to be from somewhere. It’s a credit to our region to have our own category, but I wonder if it doesn’t hurt in some way, too.

GI: Mississippi is one of those weird, amazing, dark places with a lot of beauty and a lot of awful things in its history, which makes it fertile ground for fiction. What do you think non-natives get wrong about Mississippi the most? Why are outsiders always trying to explain places in the South to others?

MFS: Just going by questions I get from people unfamiliar about Mississippi, I think one of the misconceptions is that everything is about race. I’m always surprised when someone says to me, “You don’t write about race.” One of the reasons is that there have been hundreds of novels written about race in Mississippi, and there will probably be another hundred written in the next couple of years, some by writers who have never set foot in Mississippi, which I always find odd in a special kind of way. We have our problems. But these problems are not unique to Mississippi. I wish they were. It would be a fine world.

As to why outsiders try to explain places in the South to others, I have no idea. When I used to live in France, I would come home for a visit, and there would always be that person at the bar who wanted to tell me everything about France. What the people were like and what the food was like and so on. And then I would find out that person never set foot out of the country. Who knows? When I’m on the road with a book or doing an interview, I try to portray the best of Mississippi, and be positive, because that’s the only way to [bring] change.

GI: My high school counselor told me my English wasn’t any good so I should aim to stay close to home and maybe apply to some local community college, so I went to the University of Texas at Austin and got a PhD. When folks ask me why I never use the “doctor,” I say I’m waiting until I see that counselor again. When she goes, “Hey, Gabino!” my reply will be “That’s Dr. Iglesias to you, motherfucker.” What’s your story, Dr. Michael Farris Smith? Why not use the degree like every other pretentious doctor out there?

MFS: I think the answer to your question lies in your question. And also I don’t really give a shit. It was a means to an end.

GI: Let’s talk about Blackwood. It’s an outstanding novel. What was the seed of it? When did you know it’d be a few different narratives coming together?

MFS: The seed was the landscape, this creeping, smothering kudzu that has taken over the South. After Rivers, I never thought I’d have a landscape be the beginnings of a novel again, but then it happened, and I loved the idea of this haunted valley, draped in kudzu, on the edge of this stagnant, dying town, where people seem to be stuck in a photograph.

I really had no idea where it would go, and I rarely do. But at least I typically have an idea for a character in a tight spot. Not so much in the beginnings of this, though we certainly got there. Maybe that’s how this ended up being a little bit more of an ensemble cast than I usually have. All of which had me wondering myself how it would all come together. It was a different kind of storytelling, working so many pieces into the whole, and I have to say it was pretty satisfying the way it delivered.

GI: Blackwood is green like kudzu and earthy like Mississippi soil in some passages, but it’s darker than a pool of ink at midnight in others. In fact, I’d argue it could be called a horror novel from time to time. What are your thoughts on genre, especially when talking to your agent or your publisher, both of whom surely care about marketing?

MFS: I agree with you—in many parts of both the writing process and the story itself, it felt to me like horror, which seems to be a natural next step from Southern Gothic. It was the horror elements that kept me from sleeping, that gave me bad dreams when I did fall asleep, that kept me wondering if someone was there in the dark when I woke up. I never talked to my publisher much about it. The Southern Gothic narrative was so prominent [that] when we began to talk about what the book would look like and how it would be presented, I knew the horror aspect would just ride along.

It has been different, though, with the film adaptation. I think the horror tag will be more out front and drive toward that audience. You gotta call it something, so might as well call it horror, especially since I have yet to see Southern Gothic listed as a category on Netflix. Though it should be.

GI: The timing of the pandemic wasn’t great for Blackwood. How have you been coping? What are you doing to get the word out about the novel and how can we help?

MFS: The first thing I did was I tried to get some video out there of a reading, and my pal and filmmaker Joe York helped me put together a pretty creepy three-minute reading in a damn-near-condemned building. I was able to share that on social media and with bookstores and put it on my website in place of “Events.”

Otherwise, I’ve been saying yes to every Zoom request from bookstores or book clubs. I’ve been more active on social media than I usually am. I’m also hopeful that the book is affecting whoever is reading it and that they are talking about it with other readers, much like you are doing. It is really appreciated, and certainly every other writer with a book out in the last couple of months is very appreciative of any attention being thrown their way.

I’ve been coping through a seemingly earlier happy hour every day.

GI: You say Mississippi and someone yells, “Read Faulkner!” I get it. I’ve done it. I love him. However, Faulkner isn’t going to put a new book out any time soon. Can you recommend a few living writers you’ve recently read and enjoyed?

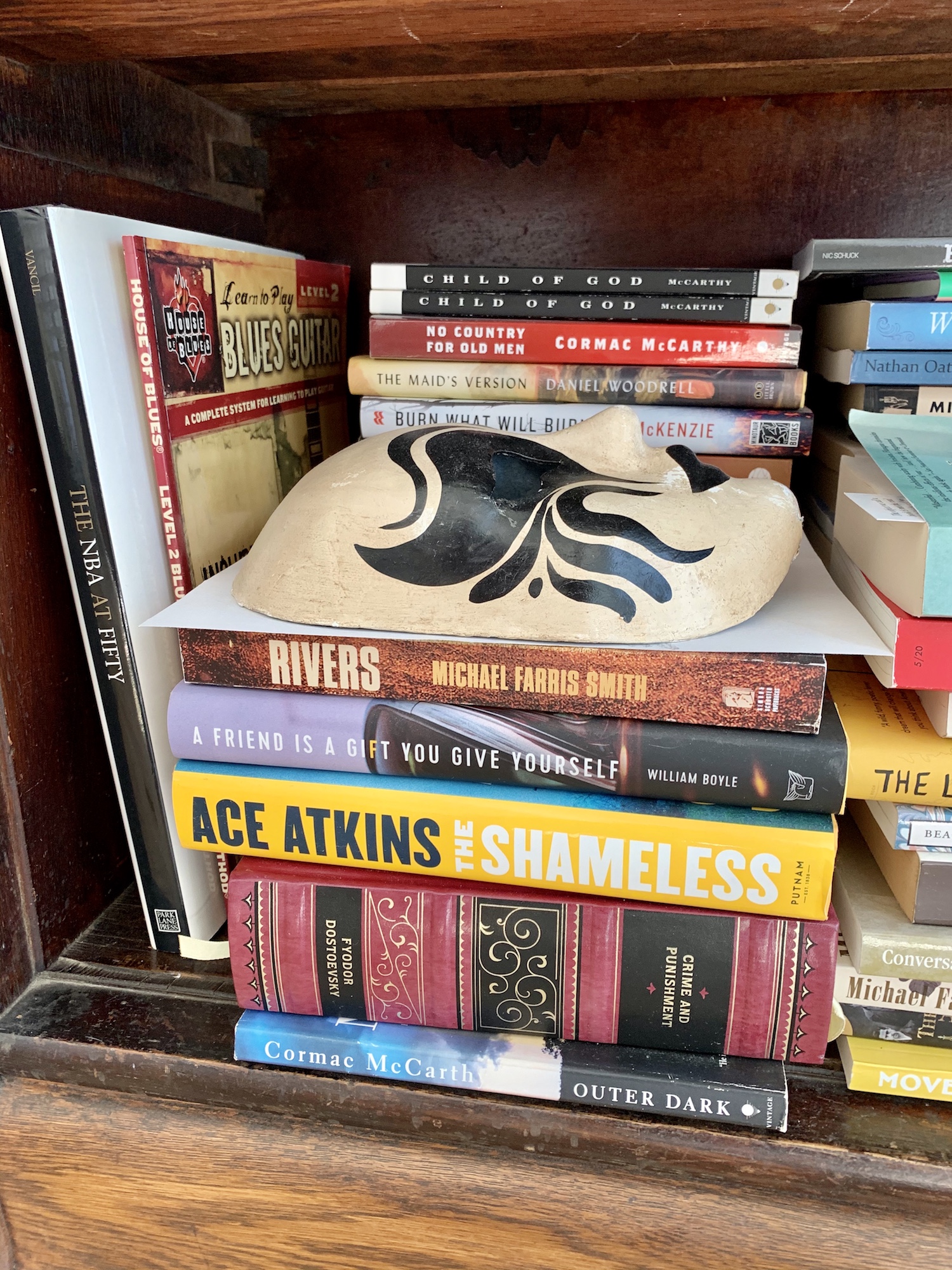

MFS: Absolutely, especially relative to the question you just asked, all of these have new ones out: Ivy Pochoda, William Boyle, Lee Durkee, Mary Miller, Ace Atkins, Taylor Brown.

GI: Even those who aren’t book collectors end up with a few signed copies or special books. The house is on fire: What books are you grabbing off your shelves before running out?

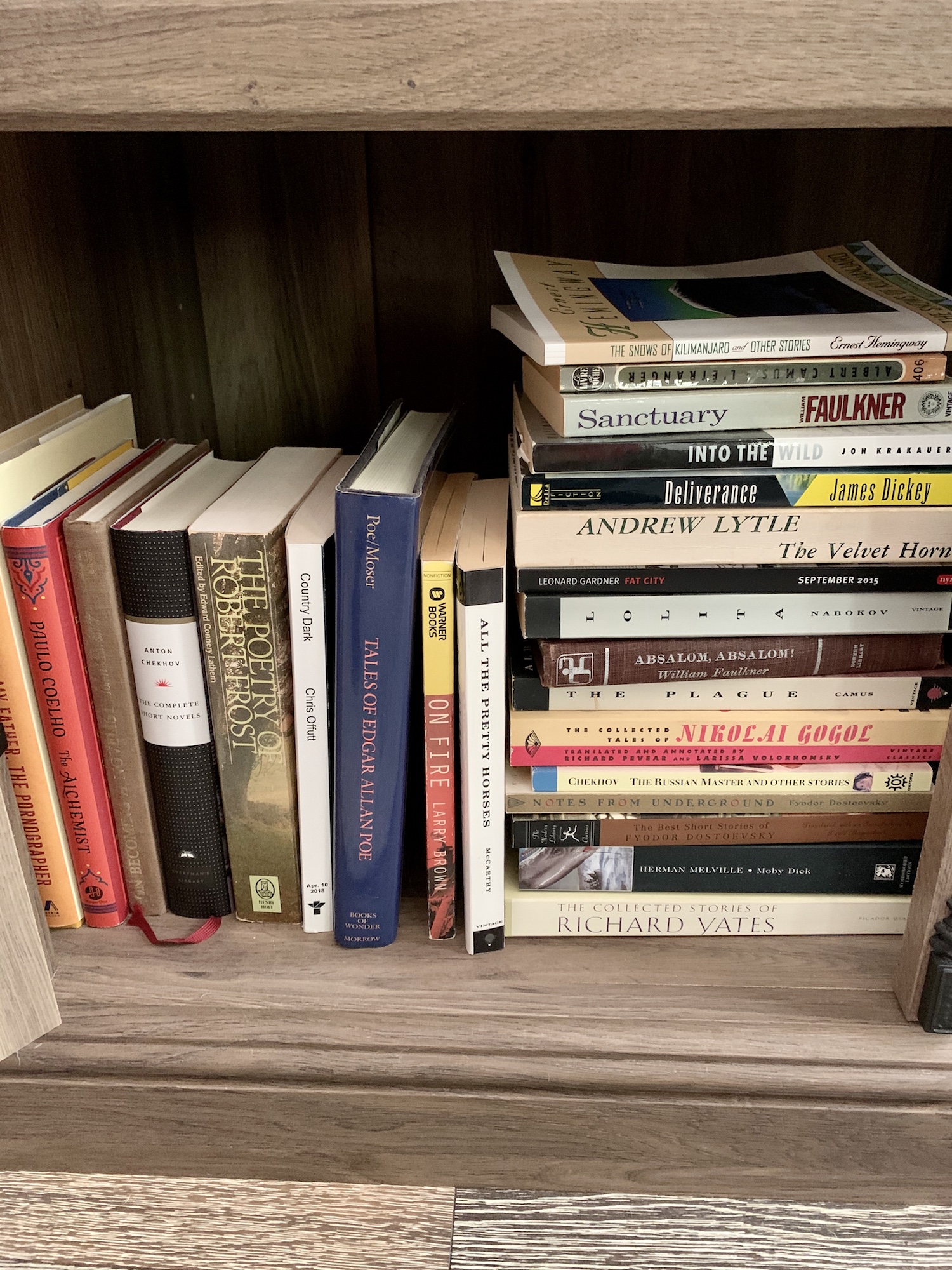

MFS: Legends of the Fall by Jim Harrison, Father and Son by Larry Brown, The Ballad of the Sad Café by Carson McCullers, Provinces of Night by William Gay, A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway, Light in August by William Faulkner, Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys.

GI: While there are certain elements of cohesion in your work, every narrative is different. Do you start writing and see where it goes or is there a vault of storylines you’re working your way through? How do you know what’s a good idea for a short story and what idea is a novel you want to spend a chunk of your life writing?

MFS: I’ll answer the second part first—I decided ten years ago, no more short stories. I would throw everything I had into the creation of a novel or development of a character in a novel. So, for that reason, I really quit thinking about short stories a while back.

As to the first part, I start writing and I see where it goes. After working, I might make a few notes so I’ll have a jumping-off point the next day when I sit down, but I don’t want to look too far ahead. I want to discover as I go along. I want to work it out in the writing. I want to be curious when I sit down to work. I feel like those things go a long way in transferring to the reader once the novel is delivered—that feeling of discovery, of uncertainty about where we are going, the curiosity to turn the page and move to the next chapter.

GI: We’re all stuck home. Any pandemic reads you’d like to recommend?

MFS: In addition to those writers I named above, I’ve found that doing some reading for the soul has been good for me during this time. There is a book I discovered by accident over twenty years ago, when I was feeling alone, on the verge of trying to write myself, that gave me the courage and the hope, not just from a creative standpoint, but from a being-alive standpoint. That book is Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke. It changed my life, and I have read it over and over, particularly whenever I feel lost, or doubtful, or just need to remember who I am and what I want to be. This has been a good time to read it again, and I would suggest it to everyone.

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, professor, and book reviewer living in Austin, Texas. He is the author of Zero Saints and Coyote Songs and the editor of Both Sides: Stories from the Border. You can find him on Twitter @Gabino_Iglesias.

More Interviews