That Weird and That Good

Reviews

By Gabino Iglesias

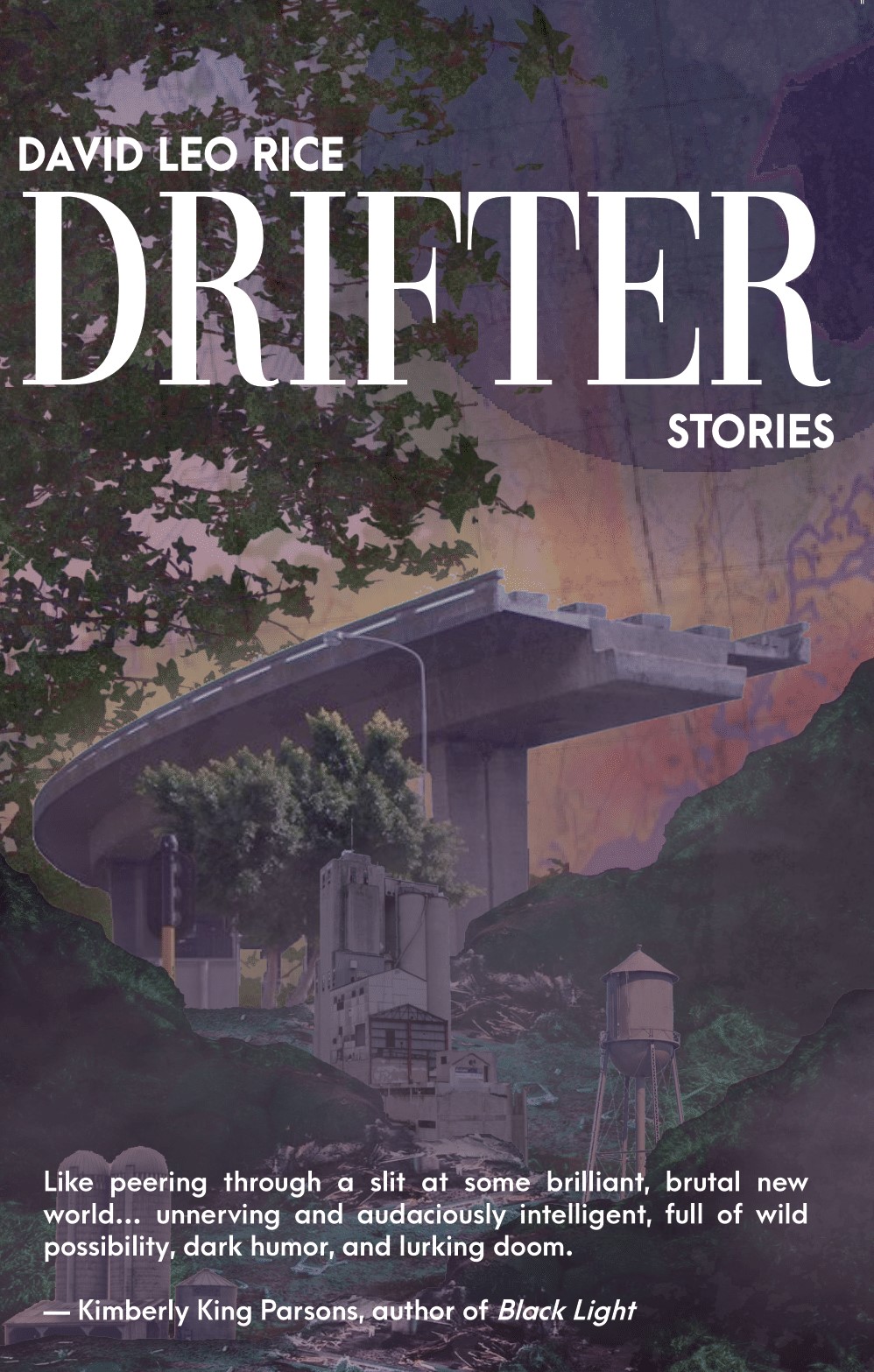

There’s a narrative space where reality morphs into something unknown, certainty crumbles, and preconceived ideas are revealed as useless. The short stories in David Leo Rice’s Drifter include elements of surrealism, science fiction, horror, and literary fiction, but they refuse to respect rigid distinctions between genres. Instead, they opt to obey a set of rules imposed by Rice’s style and voice, which exists somewhere between the magnificent weirdness of Thomas Ligotti and the overwhelming sense of uncertainty that characterizes horror maestro Paul Tremblay’s novels. In fact, Rice’s voice, at once elegant and strange, shines in each tale, making this his most impressive book to date.

On the surface, the sixteen stories that make up Drifter have nothing in common except for Jim and Joe, two recurring characters in Rice’s work who appear here in “The Brothers Squimbop” and “The Brothers Squimbop in Europe.” However, underneath the book’s surface, several forces of cohesion are at work, giving the collection a sense of unity.

The tales in this book sometimes share a format—a normal occurrence morphs into an outlandish nightmare—but that’s not always the case. Moreover, while Rice fills out some of his prose with superb and imaginative descriptions, he uses understatement elsewhere to craft stories that pack much more of an emotional punch.

None of the stories that occupy Drifter’s approximately 300 pages can be easily explained and analyzed in a paragraph or two. As always, Rice’s work here is layered and complex. For example, in “Egon’s Parents,” a young man named Ed kills a child named Egon with his truck. In the aftermath, Egon’s parents have Ed move into their house and take the place of their son. While the premise itself is odd, silence and tension turn the experience into a waking nightmare for Ed, and readers are dragged into the same psychological maelstrom that threatens to swallow him.

Perhaps the first true gem of the collection is “Circus Sickness.” Somewhat reminiscent of Joe Lansdale’s The Drive In, this story follows two kids who go to the circus and become trapped there forever, their happy lives slowly turning into a gloomy existence of perpetual repetition. It’s also one of several stories in which a video store makes an appearance.

We fell in with the procession, leaving behind the video store where we’d spent all our time since school let out on June 16th, handling movies like dormant rattlesnakes, praying some of their power would rub off without killing us. We were nine now, so we’d seen a lot—it was the summer The Silence of the Lambs came out on video—but the jester with our whole town behind him was something else.

“Out on the Coast” fully embraces strangeness and melancholy, mixing them in a way that makes this story the perfect introduction to Rice’s work. In it, a stranded whale spends decades dying. But the story isn’t only about the whale’s gigantic, decaying body. It’s also about the way its presence reshapes towns—and touches individual lives.

According to the Stillboro County Citizen’s Almanac, reissued with addenda every two years between 1912 and 1988, the whale that washed up on shore and came to cover most of the Northeastern Coastline in March 1929 was between 181 and 182 miles long. All along the whale’s body were caves that teenagers had carved with garden shovels, hideouts and forts gored into its sides, strands of dry muscle hanging from the ceiling like the guts of a giant pumpkin. They huddled in these caves to smoke and talk and touch, wrapped in blankets in winter, wearing nothing but swimsuits in summer.

“The Hate Room” is one of the darkest stories here. Two men, who become lovers, open a B&B on a small Japanese island one of them wins at a reality show after ending up broke and desperate. Hoping to attract guests, they add a mediation and relaxation room, but something there brings out the hate in people, leading to awful consequences.

Another gem is “The Brothers Squimbop in Europe,” a story full of stories. It follows the eponymous brothers as they scrape out a living by convincing people doom is coming and only they can help. Along the way, it provides a showcase for some of Rice’s most vivid imagery.

As the weeks became months, they expanded their repertoire, deviating from the classics and ranging more boldly into tales of their own design. “Werewolves are stealing in from the deep Carpathian woods at night,” they told the people of one town, “and impregnating your cows, so that any calves born to them must be buried in molten iron, lest they grow into three-headed demons, their milk the fibrous nectar of the Gnostic Satan, who will, in time, be born to a human mother and crawl into your pantries to sup.”

Drifter is, in many ways, about drifting, and it takes readers both across continents and between realities. But it is about drifting in a larger—and potentially darker, weirder, and more sinister—sense. As we drift through the stories, change is the only constant and uncertainty obliterates every anchor. But we go along willingly because Rice is at the top of his game here. He makes the transformation of common events into ugly wounds on the face of reality so utterly enjoyable. Drifter should secure Rice a place on the same list as the aforementioned Ligotti and Brian Evenson, one of contemporary literature’s most versatile voices. The writing here is that weird, and that good.

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, professor, and book reviewer living in Austin, Texas. He is the author of Zero Saints and Coyote Songs and the editor of Both Sides: Stories from the Border. You can find him on Twitter @Gabino_Iglesias.

More Reviews