The Syntax of Skateboarding | An Interview with Kyle Beachy

Interviews

By Odie Lindsey

Way back in May, as the unvaxxed were on murder break, I drove to the home of some dear pals in Louisville, to commune with our mutual friend Kyle Beachy. In a backyard in Germantown, our masks stuffed in pockets, we debriefed each other on our lockdowns, and praised the good road ahead. There was local-batch, Kentucky bourbon and a firepit, goodness gracious.

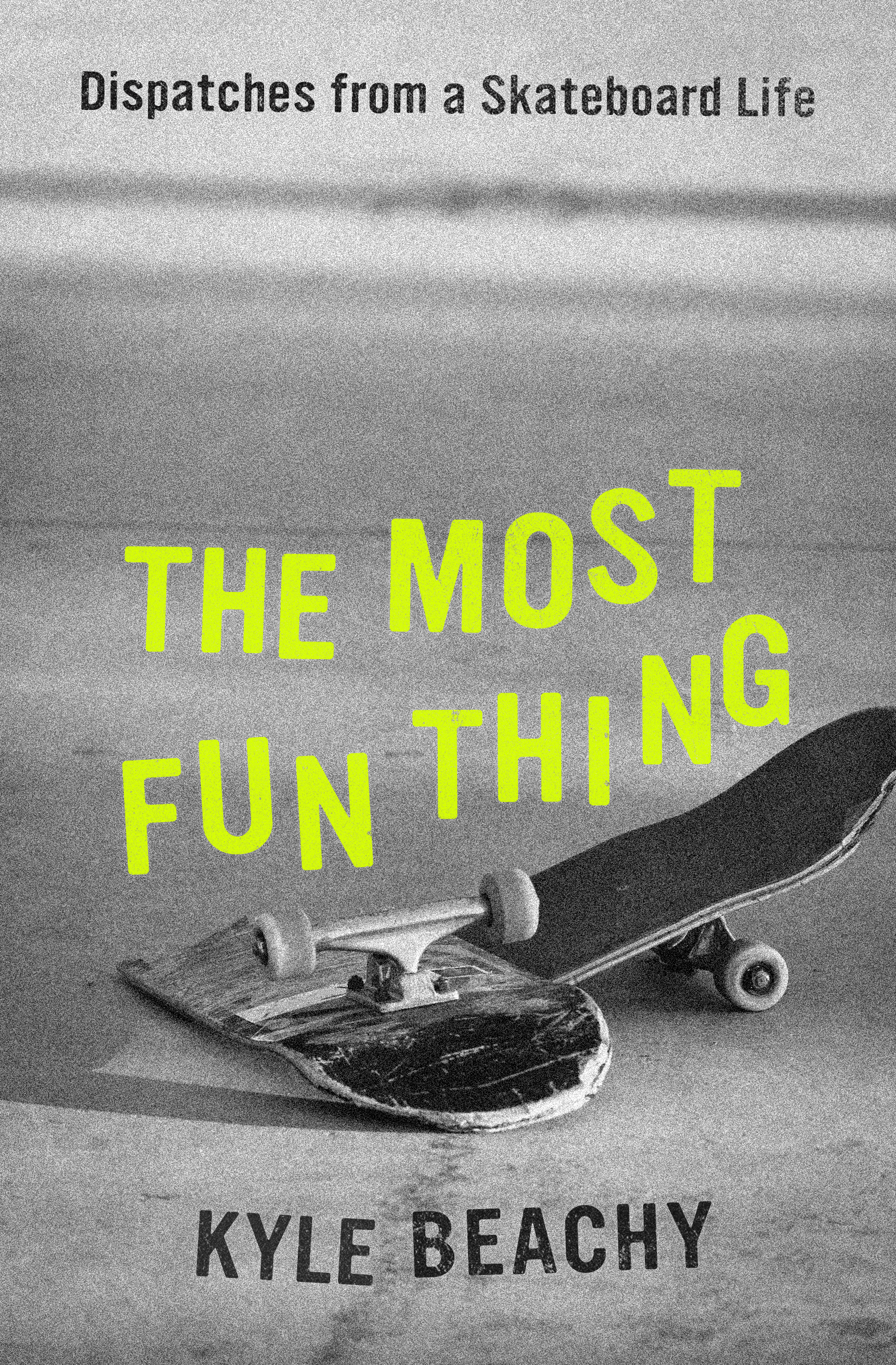

Kyle had just completed an interview with Thrasher magazine, a build-up to his new essay collection, The Most Fun Thing: Dispatches from a Skateboard Life. The feature was something he had dreamed of for decades (although I bet he never envisioned being profiled as an author).

A novelist and tenured professor, and . . . well, an over-forty, Kyle may never land the Thrasher cover photo. This is okay. The Most Fun Thing is as much about process as documenting performance. In it, his encyclopedic knowledge of skate “parts” (a.k.a., films), bios, technicalities, even feuds, rolls into contemplations of Marilynne Robinson or Maggie Nelson. The etymology of “baffle” is traced by way of Gerard Manley Hopkins and the philosopher Richard Kearney. What’s more, the book is grounded in memoir, vulnerable and direct, and often a stage for Kyle’s wit. “My kickflip is bad,” he confesses. “For a committed skateboarder, to have a bad kickflip is akin, perhaps, to having an adult dog that recognizes but does not respond to its name.”

The essays consider the practice of making meaning. Beachy’s successful novel, The Slide, ushered in questions about authoring—about the showcasing of work, versus the how and why, the joy of making it—until he followed a suggestion to write like he was “going out skateboarding, not going out filming” skateboarding. He wrote an essay, then a series here and there, about skater history and culture, itself an identity of seeming contradiction. Typecast and not. One-liner and not. Commodified and not. Outsider and not. Looking away from fiction also led him to other, most challenging narratives: himself, his marriage, his reckoning with both.

True to its title, The Most Fun Thing mines the value and ritual of fun—as affixed to individual reward, the global marketing of authenticity, or even the literary-industrial complex. “Were I to rank types of writers by how much fun they are capable of and interested in being,” Kyle writes, “all the way down at the very absolute bottom of the list would be erudite literary critics who suffer for believing that they are fun when they are absolutely not.” Topics run the gamut from Nike and Nyjah Huston, to selling and self, or the very idea of substantiation. The text can rollick, as when he joins celebrity skateboarder, Chaz Ortiz, at a daytime party at a bigtime nightclub:

It was three o’clock in the afternoon and I was shouldering between men with perfect cuticles and very white teeth, women who generally did not see me, and a server holding a flaming sparkler. On the way to [Machine Gun Kelly’s] table, we had to keep stopping so Chaz could be the valuable part of someone else’s selfie.

Kyle is now a premiere chronicler of skateboarding. (Or he’s not, if you scroll through select comments smacked to his essays and podcasts. Which he does.) And me? No matter how much I want to hold court on the subject, I am a middle-aged baldie who ditched his Zorlac in ’86. As such, our Q&A travels adjacent avenues.

Odie Lindsey: Can you speak to the relationship of rhythm and movement, as can be applied to both skateboarding and prose?

Kyle Beachy: The activity of skateboarding is circular, or looping, anyway, and defined largely by repetition. So there’s all kinds of movement and backtracking and also a great deal of lingering. And, throughout the experience, a skater is always watching. That could mean other skaters, or traffic, security, and whatever environmental factors are in play. So there’s the rhythm of the body plus the movements of space and time per the location itself. Which is to say there’s a lot going on there.

And while I’m not real good at speaking about rhythm in prose, I am quite interested in syntax and the distinction between additive or paratactic sentences that grow as they go and seem to roll a bit, gathering momentum, as opposed to subordinating or hypotactic sentences that traffic in pauses and interruptions. In these terms, skateboarding’s syntax really depends on whether we’re discussing the activity itself (subordinating) or the films that serve as the activity’s primary literature (additive).

And now I’m a little worried I’ve kicked this off by overcomplicating things, so please follow up if any of this feels obfuscational or whatever.

OL: Pass! And/but, related to, in each discipline—if we can affix that term to both activities?—there seems to be a balance of improvisation and control, a constant renegotiation of spontaneity and procedure. Is this so? Can we apply kindred notions of revision, of precision?

KB: As with any performance or visual art, the skateboarding that feels most compelling and alive manages to convey the authority and awareness of discipline and training without sacrificing the potential for feral mayhem built into its medium. I’m not sure what role this mayhem plays in prose these days—it seems more and more the domain of poetry, at least in the US. I do know that, in both skateboarding and writing, it’s always very clear when the feral bits have been revised out. The Olympic skateboarding events, the men anyway, were boring and lifeless and tame and procedural. The women were way more interesting.

OL: When it comes to terminology or theme, and to what might be considered “insider” skateboard culture, how did you define your responsibility to the unfamiliar reader? As in, how did you navigate the rub of 101’ing a non-skater while negotiating the risk of isolating your peers?

KB: Well, the unfamiliar reader was mostly my editor’s concern, and he did a real good job of pushing for clarity when my own instincts didn’t go far enough. The good news is that a book is a cumulative technology that always requires some degree of learning along the way. And I guess that is the source of my own personal motivation, beyond my editor’s, in reaching unfamiliar readers. I don’t want them to think that the stuff they see in popular culture—competitions, the pantomime of skating they see in Old Navy ads—is all there is. The sort of soft argument in all this is: “Hey, this thing we accidentally invented last century and which, you know, didn’t go away even though it certainly could have? Let’s maybe have a look at this because it’s way, way more interesting than you think.”

OL: How much influence, or say, affect, can be detected when watching someone skate? Can you tell when an individual is showcasing a known style or influence if not outright mimicking or ripping off? (And is it a problem if they do so?) Does this process shift as a skater matures? As with writing, can you detect a lineage of influence?

KB: Oh, you can see echoes of affect in a skater’s body. It’s there in a skater’s push or general posture, the way the person carries theirself. Often it’s in the hands, the bend and tweak of wrist or shape of fingers, the way the arms rise during certain motions. Some of these are overt enough to consider homage, and others are indicative of broader, culture-wide shifts in value, like the way everyone started keeping their hands down around their waists when Antwaun Dixon (who was himself mimicking Gailea Momolu before him) ushered in an era of performative ease and conspicuous control. So, mimicry is the norm for just about everyone until, occasionally, the individual emerges from whatever bouquet of pastiche has informed their development. Of course, the vast majority of skaters quit before this can happen.

OL: Speaking of, your prose exhibits a distinct style. By syntax or structure, your craft is not invisible (or, in my opinion, interchangeable). Thus, MFA in Writing professor Beachy, how does a writer determine when their personal aesthetic, their affect, overshadows the base utility of meaning?

KB: I don’t believe meaning is ever distinct from style. In terms of pedagogy, I teach toward clarity because young writers, like young skaters, tend to wear their influences in bright flashing neon signs on their foreheads. So, the correctives I offer tend toward purpose, utility, and so on. But I also try very hard to isolate potential little shards of compelling style shining in whatever they’re doing by asking them to own the style a bit more than they want to. Why this flourish? Why this repeated syntax? What do you have in mind? The answer doesn’t have to be convincing or anything. They just need to ask the question.

OL: Skateboarding lore, biography or otherwise, often contains at least a dab of bullshit. Can you speak to the idea of mythmaking, or even fiction as an extension of this practice? Is bullshitting woven into the nonfiction of The Most Fun Thing?

KB: Well, lore is bullshit because narrative is bullshit. Right? I mean, of course the point of lore is primarily to convince, which these days means to sell things, and selling is bullshit, always. But also, there’s really no narrative at all without bullshit, is there? Narrative is an adopted technology, and we’ve created all these other things in its image: sports, election cycles, history, really about 98% of human culture. Did you read Sarah Manguso’s Ongoingness? She’s got this great sequence where she thinks she’s going to excerpt her massive diary into something like autofiction, only to discover that, in terms of story, her diary is a grotesque, appalling thing to read. Because a diary has no strategy of narrative! Lacking any idea where it’s going it’s just happening after happening, a record of human life. It’s missing all the bullshit that would describe a beginning in ways that augur, then a middle that shapes those auguries into preparations for a meaningful ending.

There are narrative elements to The Most Fun Thing—the struggle or quest to understand; the struggle to come to peace with aging; the arc of my marriage—but I’d hope that I’ve managed those elements in ways that minimize bullshit.

OL: These essays speak to aging. Were you always aware of the body as a narrative site? Do you consider your early work, such as your novel, The Slide, to be as cognizant of physicality?

KB: In The Slide, my young protagonist’s education comes via a sequence of romantic longing, insomnia, wandering, hard labor, sex, and a substantial beating. Though, if that novel presages the work of this new book, it’s more in the way Potter, the dumbshit hero, moves through a familiar place with eyes made to see differently by the conditions of that movement. The city changes because he’s moving through it as a delivery person. Like style and meaning, I don’t suppose embodiment and perceptive practices can be separated, really.

OL: Alongside skateboarding and biography, The Most Fun Thing foregrounds literary theory and/or cultural criticism. A one-liner assumption might be that these elements—academic-intellectualism and skateboarding culture—are oppositional. Is this the case, or is this binary a stereotype? Was it difficult to merge these two spaces?

KB: You know what I think about often, Odie? The bits in Frank Conroy’s Stop-Time where he writes about the yo-yo, which he begins to describe as an abstract, weird pleasure, but only until the more familiar principles of competition and mastery take over. Once Conroy does his, like, ultimate trick, he knows he’s the best and quickly loses interest. I find Frank Conroy pretty depressing, on the whole, but I’m interested in the fact that skateboarding isn’t yo-yoing. There’s something inside of skateboarding that resists the tired, basic conceits of competition and mastery, or at least troubles them in interesting and potentially meaningful ways. And it’s not like I put it there, you know? All I’ve done is stare into the thing long enough to start making out how these interesting qualities might work.

By this point, after years of comments beneath my articles online, I’m not too bothered by skaters who treat any thinking about skateboarding as self-serious, try-hard, etc. Skateboarding is plenty big enough for us all to have our different relationships to it.

OL: The book outlines the relationship of writing and publishing to fun—or lack thereof. Whether as theme or sidebar, the essays speak to the antagonism (if not anguish) you experienced while working on a follow-up to The Slide. Did writing this The Most Fun Thing reconfigure your relationship to success as a writer? Are you having fun?

KB: This is hard to answer because I’m not really writing much currently. I’ve got notes toward projects and manuscripts in various stages of completion, but I’m not deep in any one thing. I’m having fun doing other things. Which maybe is the answer, for me, even if it’s a convenient one. My life is bigger than I realized. I have all of these other pursuits and habits and rituals. So I’m no longer beholden to or trapped by a narrow vision of success that locates writing, and novel-writing in particular, as my exalted pinnacle of meaning. I’d hope this means that when I do get back into the muck of it, it can be fun in there. Mucky, but fun.

Odie Lindsey is the author the novel Some Go Home and the story collection We Come to Our Senses, both from W.W. Norton. He has received an NEA fellowship for combat veterans, the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Prize in Fiction, and the Dobie Paisano Fellowship. His website is oalindsey.com.

More Interviews