A Digital Native in an Offline Land | Brian Phillips’sImpossible Owls

Brian Phillips will inevitably spark comparisons to David Foster Wallace and John Jeremiah Sullivan. Mr. Phillips, it’s true, comes off as another cool guy who just happens to be crazy smart, though I can’t imagine the others assembling a collection as vast as Impossible Owls. This new book reads like a series of miniature epics, filled with story-driven dispatches from every corner of the globe.

Phillips is a former staff writer for the much-missed Grantland and a former senior writer for the short-lived reboot of MTV News. Of the eight essays gathered here, five are drawn from previous gigs and three are new. That every one of them is a blast to read is a testament to the relatable persona he brings to first-person journalism.

Phillips often writes from the point of view of a digital native in an offline land. In a novella-length piece on the Iditarod, for instance, we’re told, “I was staring at a week and a half of bone-deep cold, probable-verging-on-inevitable-blizzards, baneful travel conditions, and total isolation from the civilized (read: WiFi-having) world.” Or take this passage from his tour through the tiger parks of India: “Yet I realized that in coming here to look at tigers, what I had wanted was to be in the wilderness, to be close to the thing itself, and instead I had a strange sense that I was still at home streaming nature videos on YouTube.” Phillips seems to be winking at the reader, but never in a way that obscures his curiosity about the world beyond his iPhone.

“The Little Gray Wolf Will Come” profiles a little-known (at least to me) Russian visionary with firm ideas about what it means to create great art. Hedgehog in the Fog and Tale of Tales are beloved by every Russian child and colossal achievements in the world of animation. So stubbornly experimental is Yuri Norstein’s work that it’s almost impossible to describe. I say “almost” because Phillips steps nimbly through the complexities of craft, the nods to Japanese poetry and Chinese painting, the dust ups with Soviet bureaucrats, all without getting bogged down in celluloid, ideograms, and the like. Yet for all his bold innovation, Norstein has never gained the international fame of, say, Walt Disney. One reason is that Norstein has spent almost thirty years toiling away on an animated adaptation of Gogol’s “The Overcoat.” At one point, Phillips wonders, “what if the refusal to compromise results in a masterpiece that cannot be finished? What if the prerequisite for producing great art makes a great artwork impossible to produce?” These questions cut to the core of the mythology that surrounds genius, and though there are no answers, the possibilities of what could have been turn the story into something close to Russian tragedy.

In saying Phillips covers quite a bit of ground, I should have said every corner of the universe. The hottest take in the book involves flying saucers, alien corpses, Manifest Destiny, the Cold War, and, oh by the way, Donald Trump. “Lost Highway” begins in a plane high above Roswell, “the radioactive core of the wildest conspiracy theory in American history.” From there, Phillips drives west through the desert, first to Area 51, then to the atomic test site at Trinity. Cruising Route 66 in a busted Nissan gives him time to reflect on “the suppressed hysteria of a generation that had seen the atom split, had lived through the war’s devastation, had seen humanity’s idea of itself transfigured more than once, in a few short years, and in progressively more disturbing ways.” A few pages later, there’s this dot-connecting conclusion:

I started to see [the UFO phenomenon] as less a problem of individual experience than one of cultural psychology. For a reference point here, think about the peculiar valence the word “alien” has in the Southwest—about what other group, besides extraplanetary visitors, it’s often applied to. Notice anything sinister there? Is it so crazy to imagine the UFO narrative as a kind of disguised psychic reckoning with the guilt-terror of white xenophobia? The kind of thing that you—millions of you; of us—can’t talk about, so you remake it as a myth?

Nowadays it’s fashionable to say the 2016 election hit on something deep in the American psyche, but Phillips peels back the layers of anger and anxiety #MAGA is playing to. “Paranoia,” he goes so far as to claim, “is skepticism taken to the point where it becomes faith.” With so many twists and turns, all this swerving risks whiplash, but somehow he pulls it off, and with such deep focus that it’s easy to forget just how insane our current moment really is.

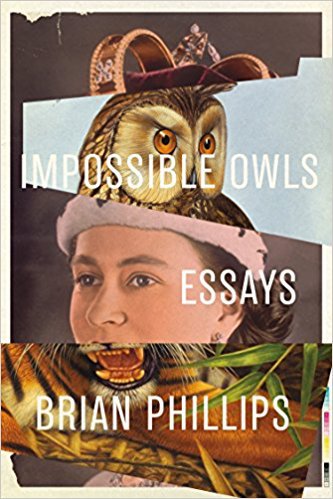

In essay after essay, an eerie figure returns with dreamlike insistence. A wide-eyed owl chases a hedgehog through the fog in Norstein’s otherworldly short-short. A memoirish ode to 90s geekdom ends in a face-off with another mysterious hooter. Owls “tend to turn up around the edges of [paranormal events],” according to alien truthers in the know. “You’ll see a dozen of them on a telephone wire, and then, around the next corner, the spacecraft.” Nuttiness aside, I’m pretty sure the owl is Phillips’s spirit animal. These essays find wisdom at the far edges of the cultural map, in the dark corners of our vision, where sometimes it can be impossibly hard to see.

Robert Rea is the managing editor for SwR.

More Reviews