A Meditation on Star Wars

From the Archives

From the Archives is a column that looks back on the highlights across the magazine’s history. In this edition staff writer Wilson McBee discusses an essay on Star Wars.

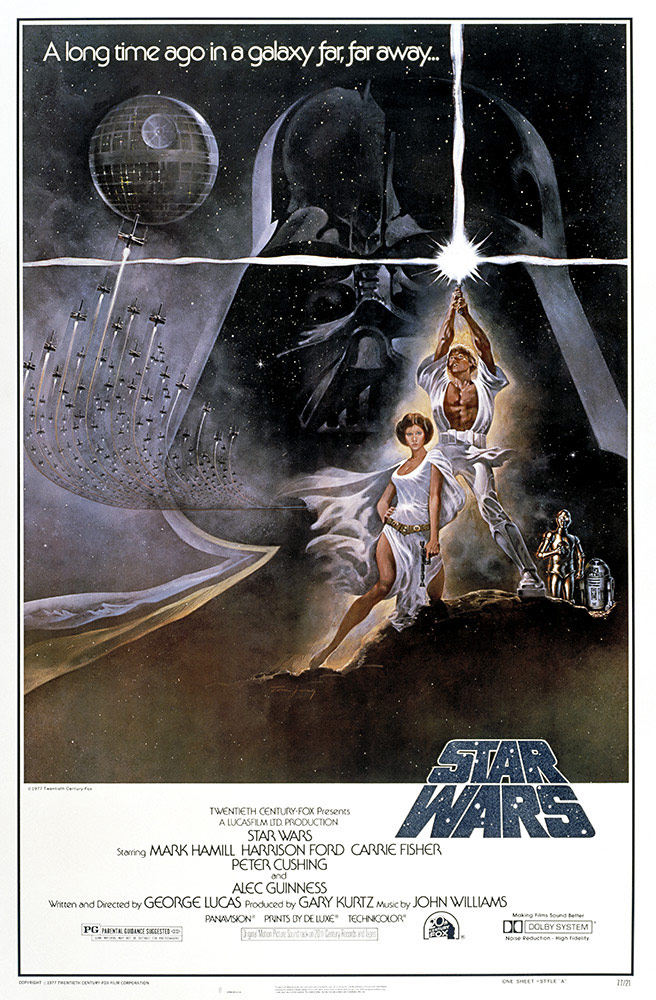

Sometimes it is difficult to believe that at one point in the relatively recent past, Star Wars was not yet a corporatized behemoth spewing comic books, video games, kids’ toys, and television shows in addition to films—a content “universe” unto itself—but a single science-fiction movie that opened at a mere forty-three theaters on Memorial Day Weekend, 1977, before quickly becoming the biggest box-office hit of the year. There were no message-board trolls decrying the practice of “retconning,” or social media accounts deploying strategic meme fodder, or fan groups pushing online petitions for de-canonization. Instead, the Star Wars experience was largely confined to people sitting together in a darkened theater and being transported to another world.

Carolyn Sumner’s piece from the summer 1980 issue of SwR captures the innocent bedazzlement of the first Star Wars summer and provides a refreshing reminder of how George Lucas’s film could be said to follow Martin Scorsese’s recent argument that cinema should be “about revelation—aesthetic, emotional and spiritual revelation.” The writer alludes to the movie’s arrival during “a season of death here in this galaxy,” and although she never elaborates on the specifics of her grief, a keen interest in the vagaries of life and death runs throughout her interpretation of the film. In the Eden of the Star Wars galaxy, Darth Vader is a “magnificent fallen angel” telling the truth about death. Of the droids C-3PO and R2-D2, Sumner writes: “They were mortals, these little machines, and so they knew love and conflict, misery, bitchiness, business, bigness.” Reflecting on the impact the film made on her and her family, Sumner lauds the movie for helping her return to a time “before we had grown up into the truth and terrors of the heart.”

Sumner’s essay is unapologetically intimate and sweetly philosophical, the antithesis of the contemporary hot take, and as the world prepares for the big reveal of Friday’s The Rise of Skywalker, it might just be the best Star Wars think piece you’ll encounter all week.

—WM

A Meditation on Star Wars

by Carolyn Sumner

“A LONG TIME AGO, in a galaxy far, far away . . .”

Some weeks or months ago my sister whispered to me, “What would you have done this summer without Star Wars?” We didn’t just go see it once, or even a few times. We went whenever we could find an excuse. We went whenever our nerves hurt too badly to leave them in the eternal compresses of the mundane. We shelled out the money and emptied our poor mortal shells behind us. We took whole crowds. We went ten at a time. I won’t say how many times in total various ones of us saw it, just that if I or they had more money, we would have seen it more. After all, as my sister remarked at the door of that theater of the stars, “A bottle of Valium costs more and doesn’t do nearly so much GOOD.” (GOOD, you know, not good.) Why at a time when I had so little money did I insist on this so?

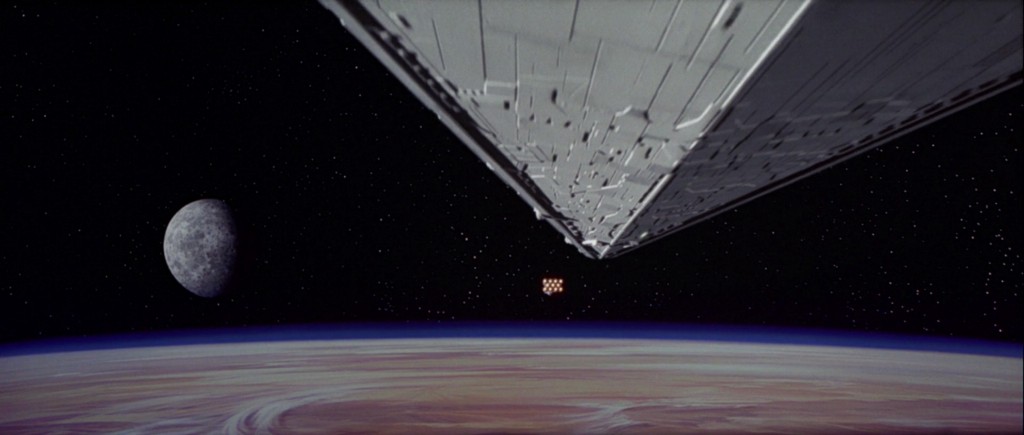

First of all, it was beautiful. It was just so incredibly beautiful to look at, and we had seen so much that was ugly. It was the season of death here in this galaxy when I first walked into that other one. Life was kind to us to return something to us in the days of taking away, to give us, opening like the deepest breath, a galaxy far, far away to go home to. When the first massive gray grace of the space ship grew to full size across the black gaps of the depths above—in the opening sequence—I had to gasp for breath. I never quite caught that breath again. I was in depths too deep for lungs, deeps of pure aesthetic joy. There was nothing of ugliness there, not even Darth Vader. Even he took my homebody breath away. A magnificent fallen angel, he. It came upon me so suddenly, this galaxy, this strange, alien beauty, drawing me out of the everyday and into the fantastic where my soul is always waiting, patiently, for me. I found my heart racing before I knew the swimming swan of a ship was chasing another, racing from nothing but aesthetic pleasure. But my heart, the poor ravaged muscle fighting the cynical gods of grief and the small wars of the everyday, relaxed out of its battles totally.

I was suddenly in the realm of the soul, pure adventure, pure quest, pure contest. And there is the real source of the movie’s beauty, the beauty that is only at first visual. I had changed realms and roles so suddenly, I hadn’t had time to grieve the going of my grief. I was in a galaxy far, far away, where an adventure is something you go on, not something you get through. It’s not so far away, I think. I oriented myself to it so fast because it is really very near. Don’t you hear it echoing in your ear like the sea while you’re hell-bent on being the shell—and nothing more? Our hearts certainly adjust their pulse to its rhythms in a way quite like the jump to hyperspace—fast and fathomless. Maybe the galaxy far, far away is really only prewar, only the last days before Auschwitz, before the heart had to face its twisted ways and the soul had to “come of age.” Before. A long time ago. Before we had grown up into the truth and terrors of the heart.

Though I am grown up enough still to be aware at moments of the actors behind the children on the screen, I am glad the younger film-makers (children of the sixties in a dreary decade) have returned to fantasy, so that we can give our children a vision of absolutes. Once, when the Princess was on the screen, my five-year-old nephew leaned over to my sister and whispered, awestruck, “Isn’t she beautiful!” He had seen so much ugliness in the last months, and now he could look up, look in, inside and see, inside eons, inside himself, the absolute beauty that is the spiritual opposition to ugliness. He could see what is spiritual and eternal within him. Listening to the Star Wars music at home with that same boy, I remarked that a certain part sounded to me like floating through space, mysteriously alone. Later when I looked into the room where he was still enraptured by the music, I saw him raise his arms at that portion of the recording, lift his legs, and rock his head and body in the chair as though floating. Star Wars was kind to us that at a time of grief, we had a way to give David back the beautiful, the spiritual, the soul inside him that has no galaxy or gravity.

I am so much a child that only a child’s comforts reach me. And in the season of grief, who is not? Elizabeth Kubler-Ross talks about a young child unwilling to speak of his impending death who once drew for her the picture of a small person being approached by a huge and menacing machine. The Death Star that hangs over us all. The star that went out, the black hole, the real machine. We are somebody’s children, and we know it. Most of all, we know it in the season of grief. Who is more than David among us, flying, or the beautiful children on the screen in their eternal contest with captivity to that machine-star and its despair?

I loved these children, these characters and their galaxy still shimmering like the Garden, far, far away. That Princess—what a girl! “Isn’t she beautiful?” Yes, and more. If only I could be a girl such as she, so mean, sharp, inventive, and free. After her meanest comment and cleverest escape plan, “I think I’m beginning to like her,” and that from Han Solo, even. Even, even, the Grand Moff Tarkin, loving her eloquent insults and bowing to her grace, “Charming to the last.” A woman worth saving because she could save the saviors, so pure straight through, so totally unmixed inside, that her white robe was a symbol for an inside immune to truth serum, or love even, that will watch her planet die before it will compromise freedom, or even the hope of freedom. And that boy, that wonderful boy, called by a destiny the mundane had repressed from his taking, so innocent and so prepared by his innocence that what seemed madness, the attack on the Death Star, is conceivable because of his practice shooting through the dangerous curves of a canyon “back home.” Unprofessional, you know. To the professionals it was a leap of faith. To the boy it was a continuation of the game, an amateur’s grand illusion.

So the soul began to put itself together before our wide eyes, joining the two sexual principles (here the principals), and unfolding, more beautiful than a monarch butterfly. The next element, the pirate. There must always be a Sancho Panza, mustn’t there? Otherwise the soul is a tyrant over the struggling and battered heart that lives in the same body with it. Han Solo, who knows space the way he knows strength, agility, how to cheat the creep that seems to be in charge of the universe. Han Solo, pirate, smuggler, who doesn’t for a moment (well, maybe for a moment) believe in the Force because he so unself-consciously embodies it. He will never trust the Force, only know that his friend is involved in some way. He will know the Force only as what it does to his friend to hear him say, “May the Force be with you.”

How we need these friends, these pirates in the real world, who know how to defend and escape its reality. How we ache for their nearness as we pursue these impossible acts, these tasks to be done, and a Death Star floating wild somewhere up there, with only instinct, stupid childhood, and the Force that will not hear our refusal, on our side. When Solo must decide whether to follow his friend into the last battle or return to his real world of distributing wealth across the cosmos, I saw the ultimate choice before the soul. The choice for the soul is not the chances in the battle. Only the heart can die, and so the issue for the heart is life and death, is courage. But the issue for the soul is different. The soul knows it will live forever, and its only choice is qualities. The choice for the soul at the moment of battle is for or against loyalty. When Han Solo comes charging in at the end, exclaiming, “You’re all clear, kid! Now, let’s blow this thing and go home!” my heart soars so that space could not contain or even symbolize it. Only when he hears his friends behind him does Luke finally shut off the computer, turn it away from where it has obscured his eyes, and give himself to the Force. “Trust your feelings, Luke. Let go. Trust the Force.”

Han Solo knows that by saying, “May the Force be with you,” he imparts to his friend some power to survive. But as he chooses loyalty, and the soul puts another part of itself, another principle of itself, in place, he learns that he also—he, the charismatic mundane one—gives the Force to the friend he follows on this suicide mission of faith.

“Trust me, Luke. Trust the Force.” The voice of one they could not kill, because he was too close to the Force, too in tune with its subtle and graceful disappearances. Obi Wan. That old man dying and reciting wisdom alone in a desert until among us wild lost planets the soul rises up again, suddenly, and puts itself together. Then merely old Ben becomes again Obi Wan, his weapon a light saber. Obi Wan. I had found a new name for the principle in the soul we call the Savior. I could not pray anymore the prayers of childhood. But now I could pray again. I had a new name for wisdom and grace. I recited the Princess’s prayer all summer: “Help me, Obi Wan Kenobi, you’re my only hope. Help me, Obi Wan Kenobi, you’re my only hope.” Praying to the savior inside me, to the wisdom and grace of my own soul that I go in search of and that finds me in the desert of death on the edge of the quest.

Most of all, though, those two robots. My heart went out to them because they were the only remnants of the heart in this world of soul. Only they could fear and lose. Only they could live and die. They were mortals, these little machines, and so they knew love and conflict, misery, bitchiness, business, bigness. How clearly I saw my own heart and conflict in them. On the outside I am pure C-3PO, all jerks and complaints, in a perpetual fastidious funk—”Oh, we’re doomed!”—but on the inside I’ve got that little loyal, chattering, courageous, graceful, blinking, bloody and bleeding knight in shining armor (though too short) of a heart, leading me on wild goose chases and crusades of greatness, R2-D2, me too. Maybe that takes the most courage of all, to have a head that knows it’s doomed, and a heart that doesn’t care. “Why I stick my neck out for you is quite beyond my capacity!” mutters C-3PO. But at the last, when R2-D2 must go on the Death Star mission, the larger robot changes his tune to truth: “Hang on tight, R2, you’ve got to come back. You wouldn’t want my life to get boring, would you?”

The adversary is not to be defeated by pleas. He is full of his own screams and can’t hear others. He is magnificent, this foe. Not the empire and all its uniformed technicians, his minor mundane workers. It is the Knight of the Empire, the dark of the Death Star, that is the foe. There was no self-conscious virility in Star Wars. That’s why the beauty. (Compare the film with the comic-book versions to see beauty contrasted with ugliness.) Evil in the movie is absolute, and so it is almost unbearably beautiful. It is not an anthropomorphic evil, but an objectification of the fallenness in the soul. It is not macho. Darth Vader is Satan, a fallen angel in a Garden world, not a small man developing muscles.

How did this angel fall? He discovered the truth, the “dark side of the Force.” He discovered that the force that animates life also threatens it. The truth is that there is death in the Garden. Satan and its angel bring knowledge, and knowledge is of death. “You’re going to die, children, all of you, inevitably.” The knowledge is so painful that it has turned life to hell, and burned Darth Vader so badly in his battles with it that he must wear a mask for a face, a mask that also breathes for him. His face and body and lungs are burned by life. And that is hell, being burned by life. So he spreads a new message in the Garden: The Force is against us. Trap the Force. Hoard it. Horde it. Contain it. Save yourselves from it, with it. Hence, an empire, letting nothing go, choking everything, slow. Slow burn.

The empire is not the enemy, though. He can choke in a moment any one of its technicians with what he controls of the Force. It is not the Death Star that is the enemy, it is the truth of death. What a stroke of genius to oppose that beautiful black machine mask in battle with the hooded face of Alec Guinness. An old, child soul against a too grown, burned-out angel. The face of pure youth and of pure evil. In that battle is ultimate concern, yet not a life and death one. Obi Wan is ancient, childlike wisdom seasoned by many deserts but still full of awe and hope, to whom the combat is still and always, after all the centuries of living, a contest, not a war, an occasion for grace and game, for the soul’s undefeatable freedom and enthusiasm. And he will not lose. “You can’t win, Darth. If you strike me down, I shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine.” The more you try to contain and manipulate the Force, the more devious, mysterious, eccentric, esoteric, and powerful it becomes, the more subtly it will embody itself as your combatant. And so it goes; there is no body in the cape of the destroyed Obi Wan. Old Ben won.

In fact, nobody wins or dies. The soul is eternal. No-body loses in Star Wars because every soul survives and triumphs with the guerrilla ships of the children. Satan is noble. He carries a noble truth, and he is hurt by it. We can’t blame him for either. Only, we must get him behind us, you know. Somehow we must make the leap into hyperspace and leave behind Darth Vader, his ticking clocks and technicians, his star fleets of ravaged-hearted demons. The issues for the soul are wholeness, loyalty, wisdom, grace, ageless as space. These issues spread widely and gorgeously before you in this galaxy. And at the end, you are crying with everything in you, “Come back to your friend, Han Solo! Come back to your heart, R2-D2! ‘Use the Force, Luke! Let go Luke, trust me!’” Win, children, win! Accept your death and deathlessness, throw the Death Star and its empire out of the Garden.

If you think the movie still is not serious (at least in effect, if not in intent), I’ll tell you that showing in the same theater at the same time was Looking for Mr. Goodbar. The previews were shown in silence, to help mute them for all the children in the theater. It was a strange effect, watching the wars and losses of the heart without sound. And as I watched people driven, putting on masks, taking off clothes, slapping each other around, bearing the bruises the body brings us, I thought I heard breathing, heavy and hot. It was not the breathing of sexual, or even homicidal, passion. It was Darth Vader, whose lungs were so burned out on life that he had to replace them with a machine. There is death in the Garden. Time is running out for the heart. So we become Satan. We decide to hoard, to build empires, to resist life, to sweeten it. We start the addiction early. Life is bitter. Every grocery store has the candy placed child’s eye high. Eating is confused with consumption from the beginning. And the children whose wide eyes could look up only to candy bars grow up and go up in the bars, looking for Mr. Goodbar still, in their old age and their dying, burned-out hearts, making furnaces of sugar’s energies. Instant energy and the eternal fires of despair. Life is sweet. And behind it, behind the seedy, garish, pathetic pick-up of a murderer, Darth Vader goes on breathing, beautiful, burning, and true.

So to those who might say Star Wars was not a serious movie and Looking for Mr. Goodbar was, I would say that Mr. Goodbar was a serious movie only if Star Wars was. If you look at life with only the eyes of knowledge, not of awe, at truth without the mediation of beauty, it is all unbearably bitter. When the only way to show meaninglessness is with meaninglessness, then Looking for Mr. Goodbar is the title of a journey that was once the Pilgrim’s Progress, a journey that went somewhere.

I am not putting down the other movie or even resisting it. But I wonder if the landing of the space ship in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, with everyone looking up like a child, discovering the language is light and music, is not a kind of sign for the Second Coming, a kind of decision in our civilization that “coming of age” does not have to mean growing up, or old, and that something towers inside us, something the heart can’t completely obscure, something that though it is ours, we must look up to in blinding light. “What are we saying to each other?” “I think they’re trying to teach us a basic tonal vocabulary. It’s the first day of school, fellas.” Maybe we’ve decided there is still something to learn after our coming of age. Maybe we’ve still got school to go to. Maybe there is truth beyond knowledge. Maybe we have to tell the message of meaninglessness with meaninglessness, that life is as it seems, just what it seems.

“We are not alone,” my friends, as the movie says. Not even now in a culture of candy and looking for Mr. Goodbar. The soul has not abandoned us. If you haven’t seen Star Wars, go see it. And go see it, and go see it. And in these difficult days, and others, “may the Force be with you,” to the fulfillment of our purpose here. ![]()

More From the Archives