Reckoning with Reality: An Interview with Chloe Aridjis

Interviews

By Wilson McBee

I

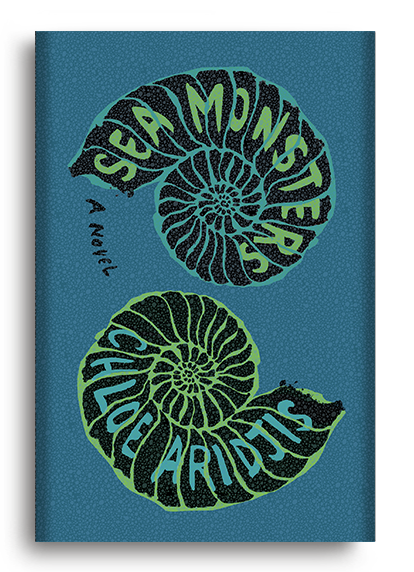

read Chloe Aridjis’s third novel, the delightfully strange Sea Monsters, amid a blitz of record-setting low temperatures as a polar vortex crippled Chicago and the rest of the Midwest with a blast of unwanted arctic air. Sea Monsters is largely set in the Mexican beach resort of Zipolite during the late 1980s, where the book’s narrator, the seventeen-year-old Luisa, has escaped with a mysterious boy she barely knows. Yet the beautiful tropical setting hardly inspired any feelings of envy on the part of this winter-encrusted reader. Indeed, this is not your typical beach book. Rather, Aridjis casts Luisa’s escapade in somber, unsettling tones. She doesn’t swim, and the beach seems to scare her more than it relaxes her. As Luisa puts it, “I did not love the water particularly, nor the heat, nor was I given to long spells of repose.”

The nominal reason Luisa has come to the coast from her home in Mexico City is that she is in search of a troupe of Ukrainian dwarf circus performers who have defected from the Soviet Union. But, as with Aridjis’s previous novels, the mechanics of plot are mostly beside the point. Aridjis draws the reader in with gorgeous and poignant descriptions of setting, essayistic digressions on history and art, and moody suggestions of violence. She’s like a dreamier W. G. Sebald, or Baudelaire set to a soundtrack of Joy Division and the Cure. Further, there’s a sense of playfulness in Aridjis that a lot of people trying to write this kind of fiction never achieve. With palpable characters and brisk pacing, her books are never a chore, even if you never really know where the story is going.

Recently I exchanged emails with Aridjis about Sea Monsters, and she also provided a playlist of songs that inform the novel.

WILSON MCBEE: How did the idea for this novel originate?

CHLOE ARIDJIS: The novel is loosely based on an episode from my own adolescence—when I ran away to Zipolite, a beach on the Pacific coast, when I was 16. I always knew I would someday write about it; the question was when, and how.

WM: You’ve written three novels, and each is set in a different city and country—Book of Clouds in Berlin, Asunder in London and Paris, and now Sea Monsters in Mexico City and Zipolite. Do you feel a conscious desire to begin each new book in a new location? If not, do you think you’ll return to any of these settings in any future projects?

CA: Yes, I do feel a certain restlessness to set each book in a new place. Each place sets off such different thoughts and associations and brings with it its own cast of characters. That said, my next two novels will be set in London/Germany and in Mexico, but in other times. In the words of the English surrealist Leonora Carrington, one should create a personal geography.

WM: You grew up in Mexico City and would have been a teenager around the time Sea Monsters is set. How much of your own experience informed the book?

CA: I like to think of it as an adolescence—my adolescence—reimagined. The central episode of the novel really did take place, as did my father’s search for me, but many of the characters and scenes are invented, and even those based on reality have been changed quite a bit. What I didn’t alter at all was Luisa’s musical taste and my own, and her interest in French symbolist poetry.

WM: Given the focus on the Ukrainian circus-performer dwarves in Sea Monsters, as well as Asunder’s museum security guards and the street character known as the Simpleton in Book of Clouds, you seem to have an interest in those who exist on the margins of a society or a group. What is it that draws you to these types of characters?

CA: Yes, that is true—I’ve always been very interested in marginal characters and am very aware of them in any public space. They represent the vulnerable side of a society, a certain rupture in the painting. They seem to inhabit a different present, and with their more urgent set of concerns are probably more detached from reality. I often try to imagine their inner lives.

WM: With music references ranging from Klaus Nomi, Bauhaus, and the Stooges to Carl Orloff’s Carmina Burana, Beethoven, and the waltz “Dios Nunca Muere,” Sea Monsters has a lively soundtrack. How important is music to the texture of this novel?

CA: Very important. During adolescence you are creating your own imaginary, and everything feeds into it, especially music, I would say. That was certainly the case for me. Klaus Nomi and Carmina Burana have something quite baroque about them, and I wanted to include that atmosphere in the book.

WM: Sea Monsters could be called a coming-of-age novel, and yet there are as many moments of disillusionment as there are of discovery. I’m thinking, for example, of Luisa’s learning that the wrestling match she attends is staged, or the later disclosure of the merman character’s true identity. What are the connections, if any, in your mind between growing up and disillusionment?

CA: Yes, adolescence seems to be a constant dance (calibration?) between enchantment and disenchantment. There’s a great deal of reckoning with reality during that so-called passage into adulthood. And how significant is authenticity within it all? I tried to explore that with the lucha libra scene and Morrissey’s autograph—if the pleasure and excitement are real, how important is the matter of artifice?

More Interviews