I Wake Up Streaming: April 2021

Movies

In this edition of “I Wake Up Streaming,” novelist William Boyle rounds up his top streaming picks for the month of April. The column’s name is a play on the 1941 film I Wake Up Screaming, starring Betty Grable, Victor Mature, and Carole Landis. While the film’s title hits a pleasing note of terror and despair, changing that one letter speaks to the joy of discovering new films and rediscovering old favorites, as well as the panic that comes with being overwhelmed by options.

Since I started doing this column last year, it seems like every month I sit down to write it means reckoning with the loss of some legend or another. In the past few weeks alone, we’ve lost Bertrand Tavernier, George Segal, Larry McMurtry, and Yaphet Kotto. It seems impossible to delve too far into their incredible careers here, but what better way to pay tribute to them than to simply go back to their work.

The Criterion Channel currently has a “Directed by Bertrand Tavernier” collection, which includes nine of his films and several interviews with Tavernier about other directors. As a crime fiction guy, I may be biased, but the two Tavernier films I recommend most are The Clockmaker of St. Paul (adapted from a book by Georges Simenon) and Coup de Torchon (an adaptation of Jim Thompson’s Pop. 1280). I also recommend Tavernier’s My Journey Through French Cinema, a beautiful three-hour-plus video essay on the enduring power of film, currently to be found on Kanopy.

As for George Segal, there are many great film and TV performances to choose from across the decades, but I’ll quickly highlight two favorites:

—Ivan Passer’s Born to Win from 1971, in which Segal plays a junkie in grimy ’70s New York City, an underrated film about “a winner who doesn’t win,” to borrow a phrase from the Safdie Brothers, who were no doubt deeply influenced by this one. It’s on Prime Video.

—His genius turn alongside Elliott Gould in Robert Altman’s 1974 masterpiece California Split, which is currently featured as part of “The Gamblers” collection on the Criterion Channel and also available on Prime Video. One of my all-time favorites and one of the all-time great hangout movies.

Larry McMurtry, of course, is primarily known as a novelist, but his contributions to the worlds of film and television are staggering. It’s a great time to revisit or discover Hud (Kanopy, Prime Video), Terms of Endearment (STARZ), Lonesome Dove (STARZ), and Brokeback Mountain (Netflix). I’m only pointing to works that are available on streaming services as I write this, and The Last Picture Show unfortunately isn’t. But I’d be remiss not to mention it for a variety of reasons, none more important than the fact that it was the beginning of McMurtry’s decades-long friendship with Polly Platt. And Platt purportedly served as the inspiration for Jill Peel in McMurtry’s excellent 1978 Hollywood novel, Somebody’s Darling.

Yaphet Kotto was an absolute legend. No one had a more memorable screen presence. As a kid I fell in love with him as Al Giardello on my favorite show, Homicide: Life on the Street. Then there were the films. Some favorites that are streaming: Midnight Run (HBO Max); Bone (Prime Video, Tubi); and The Liberation of L.B. Jones (Prime Video).

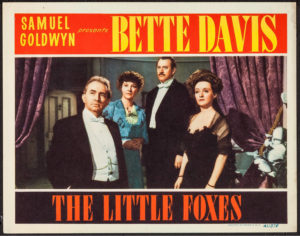

The Little Foxes (Kanopy)

I’ve been attending Walter Chaw’s film conversation series for the Denver Public Library every Saturday via Zoom (they’ve been truly great), and several guests have picked William Wyler films. Wyler’s filmography is unreal, and The Little Foxes (written by Lillian Hellman) is one of his many masterpieces. April 5 was Bette Davis’s birthday, and there’s just nobody like her—this is one of her most stunning performances. Nobody could be mean like her and nobody could give such depth to that meanness. She brought humanity to the most hard-hearted, hard-boiled characters, and nowhere is that more apparent than in her turn as Regina Giddons. This is a classic example of a film I initially saw far too young—I was probably fourteen or fifteen—to fully appreciate it. What might’ve seemed dour and dry then now seems electric and unnerving. Davis steams up the screen. It was also interesting to watch this, The Heiress, and Detective Story alongside an early Wyler boxing film, The Shakedown from 1928, and his last film, The Liberation of L.B. Jones (1970), starring Yaphet Kotto, Lee J. Cobb, and Roscoe Lee Browne, an unrelenting look at racism.

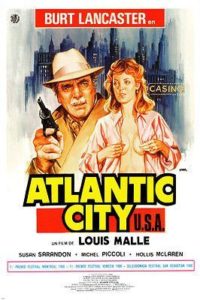

Atlantic City (Criterion Channel)

Released forty years ago this month, Louis Malle’s Atlantic City has long been one of my favorite films. I saw it first as a kid, probably around age twelve or thirteen. It’s not strange, I suppose, that I was in love with Susan Sarandon. Nor is it strange that I was drawn to such a weighty late-era Burt Lancaster performance—I knew enough about film, even then, to feel his entire career hanging heavily over his turn here as a small-time gangster. More surprising by kid standards is the fact that I was enchanted by decaying casino towns or, specifically, by places that had once been grand but had fallen into neglect through disuse or misuse. I grew up one neighborhood over from Coney Island, not a casino town, but a similarly decaying and decrepit (especially in the ’80s and ’90s), formerly majestic place. And my grandfather took a bus twice a week to Atlantic City from Brooklyn to gamble, so I spent a lot of time wondering what it was like there. Later, I realized I was also very drawn in by an outsider’s view of America, and French filmmaker Malle had painted one of the truest portraits of America I’d ever seen. Beyond that, the script by playwright John Guare is so far up my alley, I’d say that—in ways both major and minor—this has informed everything I’ve ever written. Desperate characters in desperate situations, looking for a way out or a way up, all painted against the backdrop of a place that used to be but isn’t anymore. Lancaster’s Lou has one of my favorite lines in any film. Talking to the scuzzy ex of Sarandon’s Sally (who ran off with her kid sister), Lou reminisces about Atlantic City’s golden age: “The Atlantic Ocean was something then. Yes, you should’ve seen the Atlantic Ocean in those days.”

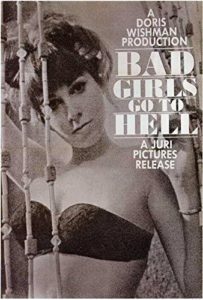

Bad Girls Go to Hell (Criterion Channel)

A collection that’s recently been added to the Criterion Channel is called Close to Home: How to Make a Movie Without Leaving the House. It’s a diverse and lovingly curated group of films that somehow—either through economic necessity or otherwise—would be classified as ultra low-budget. Legendary exploitation auteur Doris Wishman’s Bad Girls Go to Hell from 1965 is one of the most interesting. With its overdubbing and dream-dazed performances and unsettling scene after unsettling scene, it’s certainly not going to be for everyone. But Wishman has an incredible eye for detail, and it’s a mesmerizing film in so many ways. The plot revolves around a Boston housewife who is assaulted by a janitor in her apartment building, kills him in self-defense, and then flees to New York City, a move that doubles as a sort of descent into hell. Every man she meets is a monster waiting to be unleashed. Even the women have ulterior motives. New York is shot in an offbeat, beautiful way. The apartments are shadow-strewn prisons. Beds are canvases for chaos. I won’t say much about the ending, but it called to mind Twin Peaks: The Return. Utterly haunting.

Black Lizard, aka Kurotokage (Criterion Channel)

I’ve been getting obsessed with the Japanese writer Edogawa Rampo lately, and this 1962 film by Umetsugu Inoue is the first adaptation of his work I’ve watched. (It was adapted by Yukio Mishima!) Doubles, decoys, disguises, weird dolls, stuffed humans, people hidden in sofas, a woman in a suitcase, musical numbers, payoffs, stolen jewels, kidnappings, neon melodrama, a Log Lady-ish code language, cages, rings full of poison . . . it feels like Brian De Palma doing The Pink Panther or David Lynch doing Poirot or Jacques Rivette doing a James Bond movie. Or something. Wild and funny and strange. Rampo’s book was adapted again in 1968 by Kinji Fukasaku (you can find that version in its entirety on YouTube). I also highly recommend Teruo Ishii’s Horrors of Malformed Men, adapted from another Rampo novel and thematically linked to Black Lizard, if a bit darker and more twisted. This guy really had a thing for human chairs!

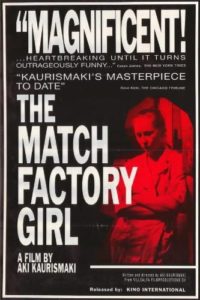

The Match Factory Girl (Criterion Channel)

I’m ashamed to say I’d never watched an Aki Kaurismäki film until last month. I’m really not sure how I’ve lived without them for so long. I’ve totally fallen in love with his work, and I’m thankful as hell that the Criterion Channel has an extensive “Directed by Aki Kaurismäki” collection featured. I’ve watched seven of his films so far, and The Match Factory Girl is my favorite. It’s the third installment of his Proletariat Trilogy (Shadows in Paradise and Ariel are the first two, but it’s not necessary to watch them in order), and it’s a noir folktale. In its economy, its portrait of the working class, its profound melancholy, its balance of cruelty and comedy (the perfect recipe for melodrama), in the way Kaurismäki turns the camera away from dramatic events, in its lack of moralizing, in creating sympathy for such a troubled character, it really reminds me of a Pre-code or silent era film. I can’t think of another filmmaker I’ve encountered whose wavelength I’m so fully on or who’s so fully on my wavelength—this is everything I love and everything I want to do.

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, and City of Margins, and a story collection, Death Don’t Have No Mercy. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His writing on film has appeared in Oxford American and CrimeReads. He used to have a blog about ’70s crime films called Goodbye Like a Bullet. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

More Movies