I Wake Up Streaming: April 2022

Movies

In this edition of “I Wake Up Streaming,” novelist William Boyle rounds up his top streaming picks for the month of April. The column’s name is a play on the 1941 film I Wake Up Screaming, starring Betty Grable, Victor Mature, and Carole Landis. While the film’s title hits a pleasing note of terror and despair, changing that one letter speaks to the joy of discovering new films and rediscovering old favorites, as well as the panic that comes with being overwhelmed by options.

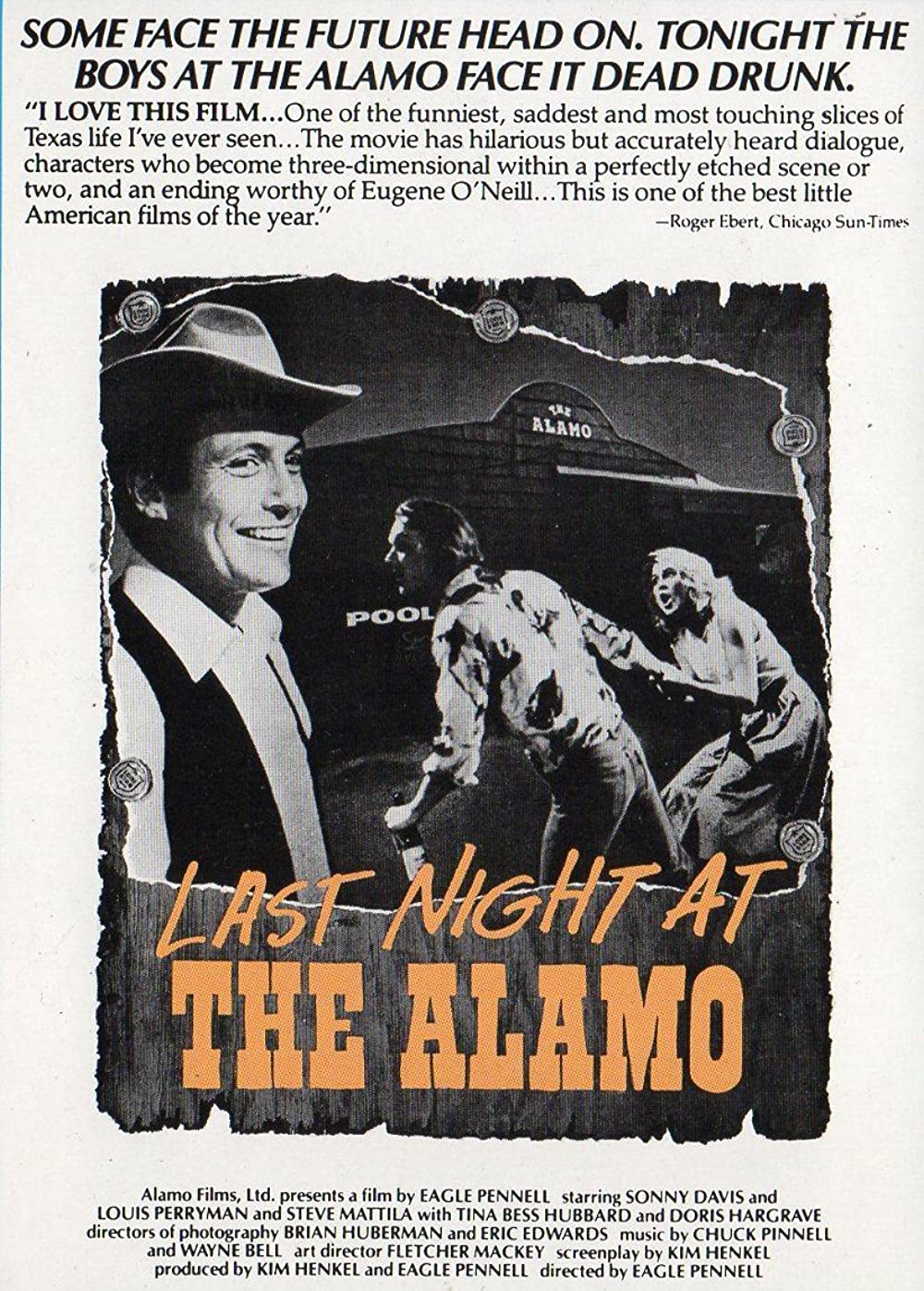

Last Night at the Alamo (Criterion Channel)

I’ve already talked about Texas indie icon Eagle Pennell one other time in this column. His short filmography was among my greatest discoveries of 2020, and now—I’m excited to say—several of his films are streaming on the Criterion Channel, collected in a retrospective called Texas Blues. I wrote about The Whole Shootin’ Match and A Hell of a Note last year, both of which are on DVD and have streamed on services like MUBI and Fandor. A documentary about Pennell called The King of Texas is also featured and has occasionally been on those same sites. The biggest draw here is the 2K restoration of 1983’s Last Night at the Alamo, which—unless you’ve been lucky enough to catch a rare screening—has only been available on YouTube as a grungy VHS rip. I came to this movie in December 2020 after seeing it mentioned in an article about one of my favorite films of that year—Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets by the Ross Brothers—and I immediately had a simpatico relationship with it. Like Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, it’s set primarily in a dive bar on its final night of business, a venue for human drama at its sloppiest, rawest, and most inelegantly empathetic. In Last Night at the Alamo, a Houston bar called the Alamo is being demolished to make way for high-rises, and the regulars come together for one last night of boozing. The movie tears into toxic masculinity and Western mythmaking. It also combines two of my favorite things: the stampeding poetry of a nearly full-time bar setting and characters yelling and cursing at each other nonstop. I saw one review refer to it as Charles Bukowski’s The Wild Bunch. You might also think of it as Eugene O’Neill’s The Last Picture Show or Sam Peckinpah’s Cheers. It’s written by Kim Henkel (whose only other major credit is co-writing the original The Texas Chainsaw Massacre with Tobe Hooper), and the great character actors Sonny Carl Davis and Lou Perryman star as Cowboy and Claude. Shot in 16 mm black and white and a wonder of 1980s microbudget regional filmmaking, it was no doubt a big influence on Richard Linklater (whose Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood would make for an effective, if jarring, double feature with this, as documents of bygone eras in Houston).

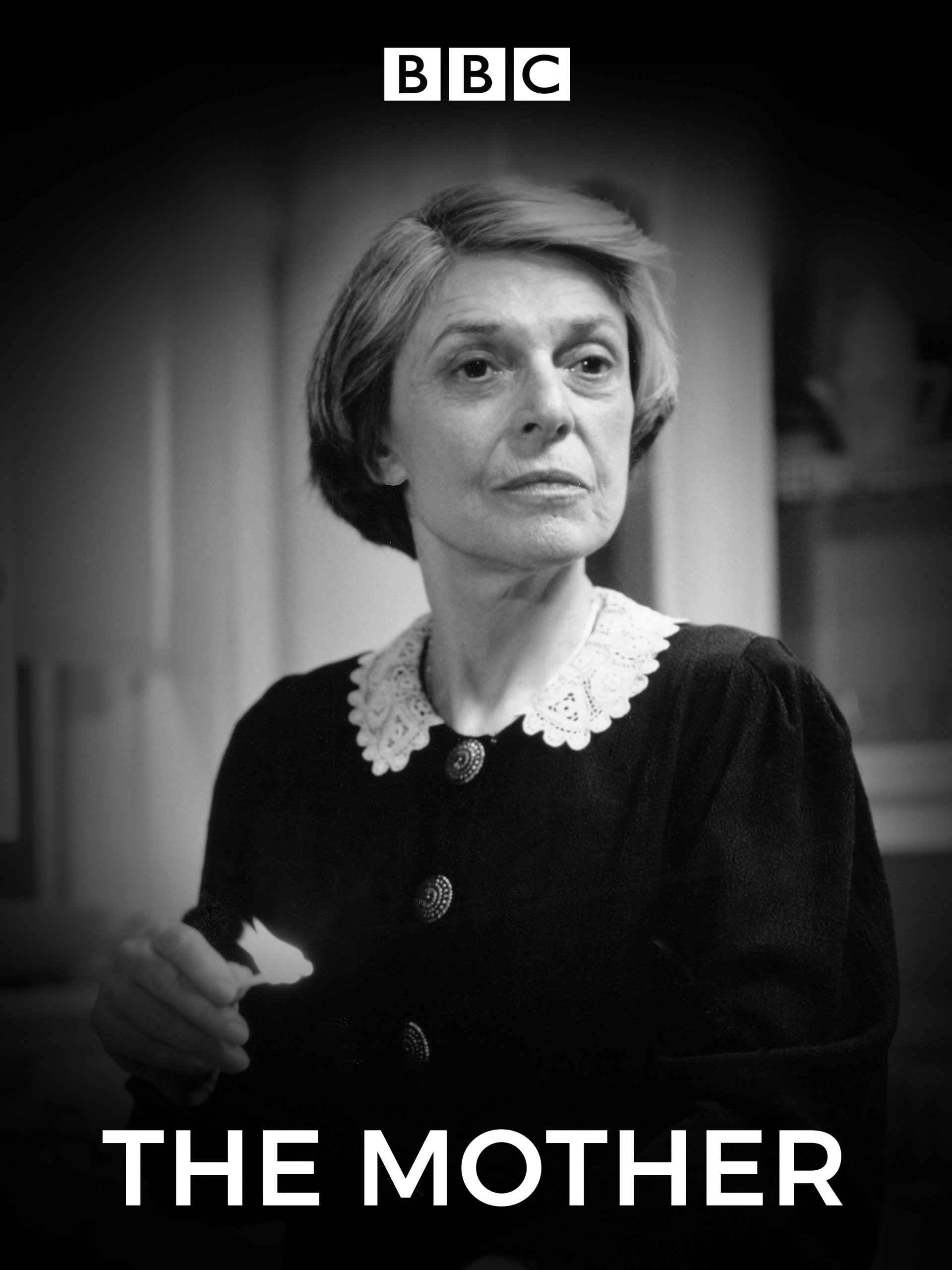

The Mother (Prime Video)

I’ve long loved Paddy Chayefsky, and Anne Bancroft is one of my favorite actors, probably my favorite, but this wasn’t on my radar at all. It’s a remake of a teleplay that originally aired live on Philco Goodyear Television Playhouse in 1954. This revival was made in 1994 for the BBC, though it was taped at studios in Astoria, Queens. Bancroft plays a 66-year-old widow, Mrs. Fanning, who lives alone in the Bronx (she’s originally from County Cork, Ireland) and is struggling to find purchase and purpose in life a month after her husband’s death. She’s intent on going back to work as a seamstress, something she hasn’t done in forty years, since before she was married. Her daughter, Annie (played by Joan Cusack), is worried about her mother, trying to convince her to relax and to let her children take care of her from here on out. Annie insists that her mother can move in with her and her family. Bancroft’s character is stubborn: “I don’t want to be some old lady living with her children.” There are memorable cameos from Mary Alice, Stephen Lang, Anne Meara, Katherine Borowitz, Adrian Pasdar, Anne Pitoniak, and Anna Thomson. Cusack’s performance is tender and lovely. Bancroft is miraculous and transfixing—breaking my heart with her line delivery and her gentle looks and her brutal and beautiful energy. And then there’s the writing. Rhythmic, full of repetitions that are real and poetic at the same time, economical, shattering. Chayefsky is just so great. I know his movie scripts and some of his plays well, and I wound up ordering his collected teleplays as soon as I finished watching this. In fifty-seven minutes, he does so much. There’s a whole world here. A whole life. Lives. Small lives. Fears and disappointments and loves and losses. I wept. This is the kind of thing I really live to discover. Seemingly simple but profound. So thankful I chanced across it. It only has one review on Letterboxd, which dismisses it as “depressing.” It’s hard to argue with that—and, anyway, I’m often drawn to works which others generally find too depressing—but that’s a limited analysis. It’s also life-affirming, a story of a woman full of courage and grit, finding hope even as she struggles to go on. Seek it out.

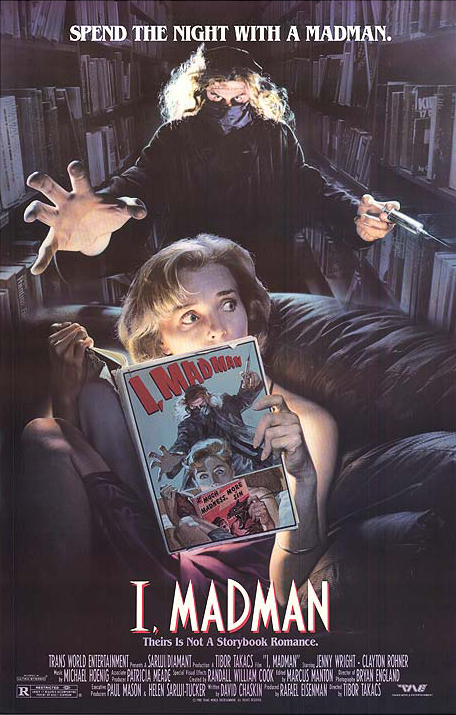

I, Madman (Tubi)

One of my favorite first-time watches of the year. Directed by Tibor Takács, who also did The Gate and Gate II (beyond that, his filmography mostly lists movies about Sabrina the Teenage Witch, spiders, tornadoes, and Christmas). The movie centers around Virginia, a bookseller who gets obsessed with a couple of pulp novels and eventually realizes the killer from the books has appeared in the real world. It often feels like a mix of Larry Cohen in Q: The Winged Serpent mode and Brian De Palma in Body Double and Raising Cain mode. There are a bunch of stunning sequences and a bunch of silly ones to balance it all out. Jenny Wright from Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark is wonderful as Virginia. She seems like she stumbled straight out of a Hitchcock movie; she’s part Kim Novak, part Janet Leigh, and part Grace Kelly. The movie works so well because it blends old-school pulp horror with ’80s slasher sensibilities in a way that’s both joyous and lurid. I’ve been wanting to watch this since I heard it mentioned on a couple of movie podcasts I listen to, and I was glad to see it pop up on Tubi. I’ll also admit that part of what makes this movie so appealing to me is the fact that one of the first stories I wrote as a kid was called “I, Madman.” I might’ve seen this title in my video store and ripped it off—I can’t quite remember. In any case, I had a slim marble notebook—the soft, almost foldable kind—and I’d scrawled “I, Madman” on the cover in black Sharpie. I must’ve been ten or eleven, which was right around the time this movie was released (1989), though I know I didn’t watch it back then. I don’t remember how far I got with the story (that old notebook was lost to a basement flood), but I remember that it was meant to be the diary of a killer. It was grimy and violent, all shadows and stabbings in alleyways, despite my curlicue penmanship and the royal blue ink I wrote in. Takács’s I, Madman is that same sort of pulpy daydream. If somebody would’ve given me a camera and the know-how back when I was a teenager, this is the exact movie I would’ve aspired to make.

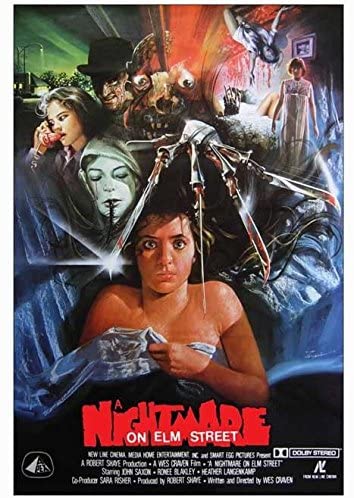

A Nightmare on Elm Street (HBO Max)

Speaking of horror movies from the ’80s, it’s not very ground-breaking to recommend one of the most iconic slashers of the era, but I just rewatched it for the first time in about thirty years, maybe longer, and was blown away. The movie was released in 1984, when I was six, and I saw it young, though not that young. If I’m remembering correctly—and memory is tricky—I watched it around ’88 in the basement of my step-cousins’ house on Long Island. Wood-paneled walls and thin carpets and the echoes of footsteps thundering down from upstairs. I was the youngest member of this new family, hanging out with mostly high schoolers who liked nothing more than throwing on horror movies during family get-togethers. I’m sure I wanted to see it. I always wanted to see things that folks said I was too young for. I gulped. I watched wide-eyed. I spilled my soda. The movie scared the ever-loving shit out of me. I had nightmares for months. I prayed every night to keep Freddy Krueger out of my dreams. I had thought of dreams as impenetrable and random before that, but then I began to understand them as a territory that could be breached, invaded. Freddy showed up often. I wandered hallways, seeking refuge. I sought crucifixes to take hold of. Blood poured from sockets in the wall. Slashes showed up across the chests of cast members in my dream. I slept poorly. I carried the fear with me to school. I tried to control my dreams. It’s dumb, but I remember trying to will Robocop to show up and plug Freddy. It wasn’t a mash-up that took. Dreams are sticky. This movie teaches you that dreams are sticky. My first viewing was also impacted by the fact that I had a massive crush on Heather Langenkamp, Nancy in the movie, who—by 1988—was starring as Marie Lubbock in Just the Ten of Us, one of my favorite sitcoms, a spinoff of Growing Pains and a Friday night staple. I worried for her. I loved her. That love traveled through my dreams. I saw her often in my mind’s eye, straining to stay awake, hidden behind bars. In any case, as I got a bit older, I caught up with the sequels and watched new installments as they were released. Though I’ve had a longstanding love of horror, I didn’t go back to the original. It had made its impression, and I was reluctant, even as I revisited other Craven masterpieces over the years. Something was in the water around the house the other night, and my wife—who watched A Nightmare on Elm Street a lot as a kid—and I both wanted to revisit it and so we did, tempering our expectations, preparing to be underwhelmed, but instead were struck by its vast complexities. The character of Freddy Krueger (simply “Fred Krueger” here in the original) is scary, but what’s really terrifying from a grown-up perspective is the way that parents and adults behave; after all, it’s their primitive murder of child killer Krueger—their twisted sense of justice and retaliation in the name of bringing order and peace back to their community—which transforms him into a sort of undead dream demon. For me, since I often can’t shut off my racing brain at night, the notion that there is no escape, that proper rest isn’t possible and is, in fact, the most dangerous of all things, takes on fearful new dimensions in middle age.

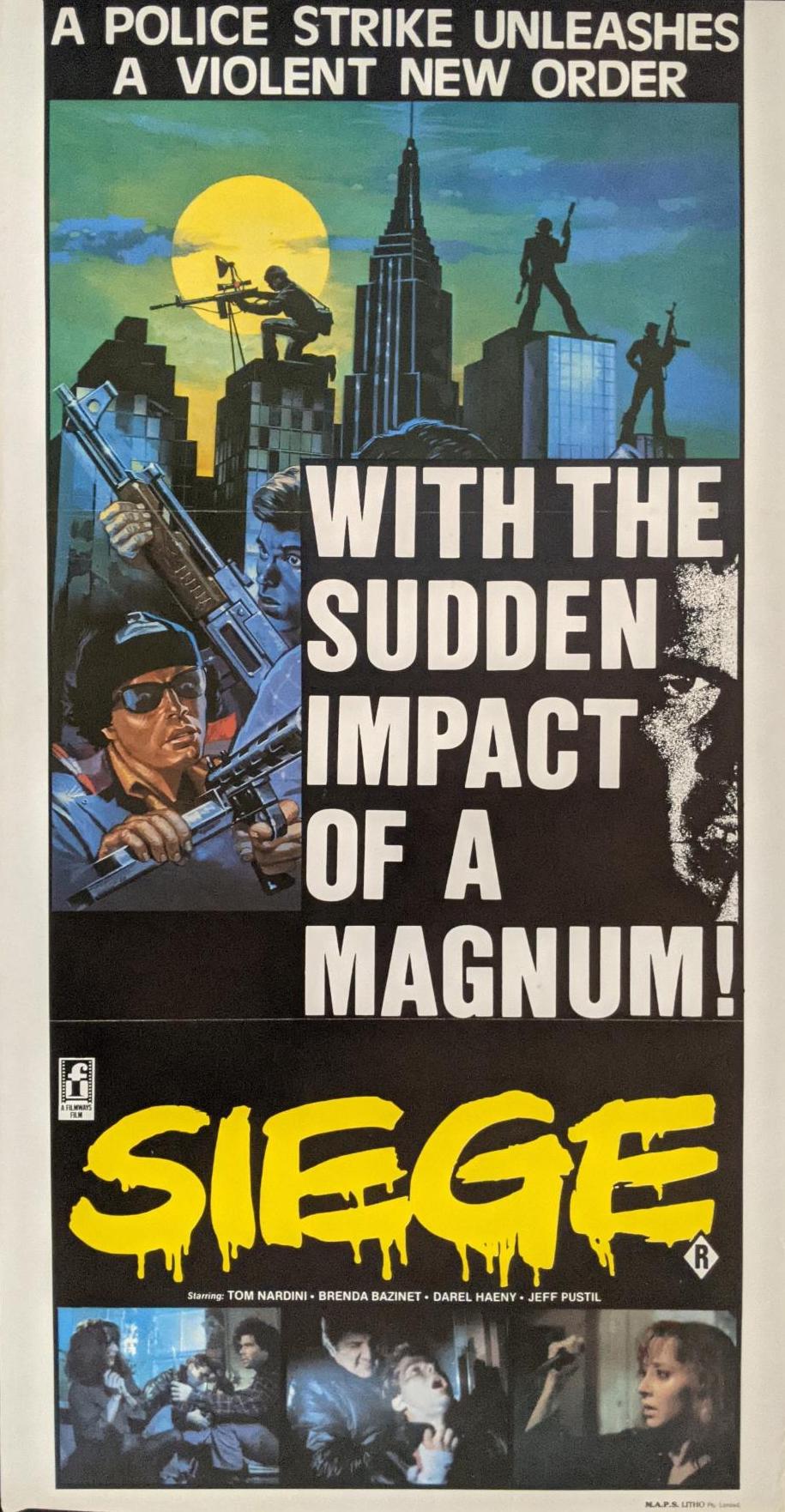

Siege (Shudder)

Another new-to-me favorite is Paul Donovan and Maura O’Connell’s Siege from 1983. I discovered it on Shudder last week, and since I’d just rewatched John Carpenter’s seminal Assault on Precinct 13, the timing couldn’t have been better. Siege (alternately known as Self Defense) is essentially a riff on Carpenter’s urban Western. It’s set in Halifax, Nova Scotia, during a police strike. When I was a kid, my mom and stepdad drove us from Brooklyn to Canada on a whim—we were big on road trips and we decided to cross the border after a brief stop in Bangor, Maine, to see Stephen King’s house—and I remember arriving in Halifax and feeling blindsided by the cold and by the shadowy cityscape. We stayed one night and then headed back to Maine. Halifax has lingered in my memory as an end-of-the-line city, and I can’t say I’ve ever seen it portrayed on film the way it is here—as a sort of dark, dystopian wasteland. The shocking and upsetting opening of Siege involves a neo-fascist vigilante group known as the “New Order” invading an underground gay bar with two-by-fours and bats to threaten the patrons. When the bartender draws a hidden weapon, things go from bad to worse fast, and he winds up impaled by a broken bottle after being attacked. The gang calls their leader to deal with the mess, and what happens next is beyond savage. Not knowing much going in, I was expecting a standoff in the bar, but the gang’s leader, Cage, shows up and executes all the patrons except for one, Daniel, who escapes into the night, his tormenters in pursuit. He seeks refuge in the apartment of a kind couple hanging out with their two blind friends and survivalist neighbor. From here, things get wilder, as the gang lays siege to the apartment where everyone has holed up and is trying to fend them off. It’s an unrelenting and gripping movie, part urban horror and part ripped-from-the-headlines ugliness. It’s an exploitation film, one that is—especially in that opening act—difficult to watch, but the darkness threaded throughout belies a real message about who the bad guys actually are. To say more would be to spoil the film’s haunting climax and even more haunting final moment. A landmark of Canuxploitation that I’m glad to have discovered.

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, City of Margins, and Shoot the Moonlight Out, all available from Pegasus Crime. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

More Movies