Let Us Now Praise Giant Men | Out There, There Is No Pain

sports

Let Us Now Praise Giant Men is a basketball column by Liam Baranauskas. In this edition he previews the 2023-24 NBA season.

In an early scene in William Lindsay Gresham’s novel Nightmare Alley, a carnival psychic’s alcoholic husband pretends to read the protagonist Stan Carlisle’s fortune in an empty whiskey bottle. “I see fields of grass and rolling hills,” Pete says. “And a boy—a boy is running on bare feet through the fields. A dog is with him.”

Stan replies, “Yes. Gyp.” (It’s an old book.)

Pete continues, “Now dark mists . . . sorrow. I see people moving . . . one man stands out . . . evil . . . the boy hates him.”

Stan, enraged, grabs the bottle and kicks it away. Seeing Stan’s agitation, Pete apologizes, explaining that he’s given Stan a “stock reading,” one that fits everybody. “Everybody had some trouble,” he explains. “Somebody they wanted to kill. Usually for a boy it’s the old man. What’s childhood? Happy one minute, heartbroke the next. Every boy had a dog. Or neighbor’s dog—”

Then Pete, exhausted and ashamed by his own drunkenness, starts to cry. Then he passes out.

Let’s be clear here. No one can predict the future. Fortune tellers and soothsayers are inevitably charlatans, trolls beneath the bridge between our sense of ourselves as differentiated, unique individuals and the fact that we’re all basically the same.

Except: this chasm, and how we bridge it, might be the key to clairvoyance.

In his book The Way of Tarot, Alejandro Jodorowsky (who, it should be said, is “absolutely opposed” to reading “hypothetical futures”) likens a tarot reading to a session with a psychologist, but through the medium of a game. The cards act as a buffer, turning the hard work of accessing Consciousness (Jodorowsky capitalizes it to distinguish what he calls “the essential state of being” from the individual act of becoming conscious of something) into play. The difference, for Jodorowsky, is that the “game” of Tarot isn’t competitive—instead of metaphorically killing an adversary by winning, the goal is to “heal the adversary and help him live.”

I’m going to read several teams’ tarot layouts and make predictions about their upcoming seasons. This, I realize, is a doomed and stupid idea. I don’t have access to a team’s psychological makeup in any real way, and regardless it’s hard to think of anything a more spiritually bereft reason to access capital-C consciousness than to use it to make sports predictions.

But contradictions are an essential aspect of basketball: a rigidly measured game that leaves its vertical plane open and immeasurable and is thus defined by those most able to transcend quantifiable boundaries—its Airs and Stilts and Skywalkers. Contradictions are also an essential part of both pseudoscience and metaphysics. In Nightmare Alley the fact that there are fraudulent mediums doesn’t preclude the possibility of real ones.

No one can predict the future. So here’s what’s going to happen in the 2023–24 NBA season.

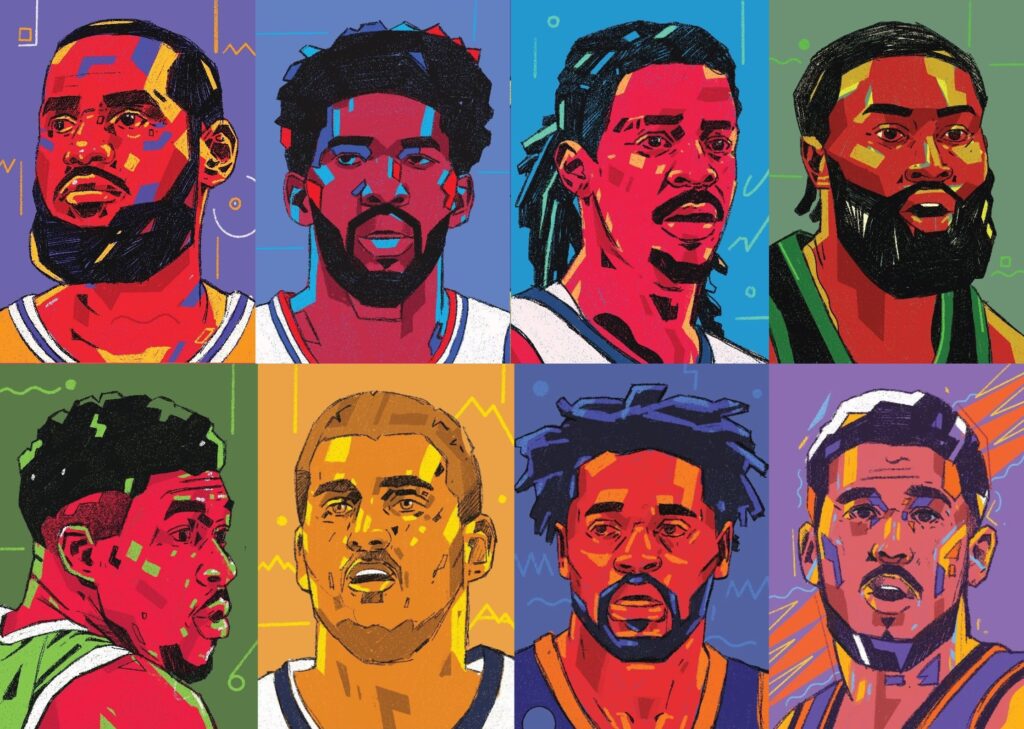

![]()

Memphis Grizzlies

Situation: King of Swords

Obstacle: Five of Pentacles

Outcome: Knight of Pentacles

A fastbreak dunk in which the dunker does a “trick” is the corniest athletically brilliant feat in basketball. It combines the useless, showoffy difficulty of a hemp-pants’d hippie’s devil’s stick tricks with the presumptuousness of a soloing bar-band guitarist’s orgasmic smirk. We don’t need Kevin Harlan screaming as if LeBron invented a time machine and went back in time to kill Hitler and then returned to dunk his severed head when he’s just doing that same windmill we’ve already seen a thousand times.

Ja Morant’s breakaways are different. They’re not flashy; they even look downright functional when he takes off. But then, midway to the rim, the parabolic arc of his leap seems to change, and both his airspeed and the degree of his ascent increase. It’s shocking and seems physically impossible. Dude figures out how to jump again when he’s already in the air!

Our young air king is also suspended for the beginning of the season after repeatedly brandishing a gun on social media, and is accused of lots of other bad behavior, from beating up a teenager to misbehaving at strip clubs. And it sucks because although there’s clearly a racialized, stereotyping aspect to a lot of the accusations (I question the reliability of the moral judgements of anonymous “Memphis business owners” who describe Ja’s grill as “all that shit in his mouth”), Morant seems to be repeatedly fucking up in wholly avoidable ways.

It’s weird to dissect stories that happen to real people as if they’re fiction. People aren’t characters. At the same time we’ve heard this one about Ja Morant before. It’s one about genius that facilitates its own destruction.

Desmond Bane is great even if his weird, cubic physique makes him resemble a Minecraft character and the Grizzlies have been winning low-scoring games that bruise you through the TV for decades. They’ll be doing that even if (maybe when) Morant gets injured after returning from suspension, and if (maybe when) he’s coming off the bench for the Hornets in two years. The Grizzlies will go 45–37, finish fifth in the Western Conference, and lose in the first round of the playoffs.

![]()

Philadelphia 76ers

Situation: Seven of Pentacles

Obstacle: Page of Pentacles

Outcome: Six of Wands

While Charles Schulz’s Peanuts is probably recognized most for its matter-of-fact depiction of the casual cruelty of children, its reductive brilliance is in its depiction of the aftermath of that cruelty. You can probably picture its silhouette—the slump-shouldered shoegazing walk of Charlie Brown after he’s been dealt another of his endless defeats. It’s a strange pose—its theatricality suggests that it’s meant to be noticed, but the act of witness makes the pain simultaneously more real and almost comical. The act of observation lightens our burdens through community yet makes them heavier by exposing our most deeply-felt emotions as ridiculous exaggerations. Somehow, my son knew to assume this posture when things didn’t go his way soon after he learned to walk. He’s never seen Peanuts.

Here’s how this relates to the 76ers: for all the bizarre stories off the court (a top draft pick having his career derailed due to an allergic reaction to some sesame chicken is probably, like, the eighth weirdest thing to happen to the team in the past decade), the 76ers’ actual basketball games have been a total snooze for a long time. Before they acquired James Harden, their offense mostly consisted of failing to throw an entry pass to Joel Embiid for twenty seconds and then someone chucking up a contested eighteen-footer, until with Harden’s arrival, it became a single, game-long flail meant to bait a referee into calling a foul. Like Charlie Brown’s failure posture, it’s not false (Harden and Embiid, the team’s flailers-in-chief, are being fouled regularly—Embiid for his physical dominance, Harden for his Svengali-like baiting of the compulsiveness of a defender’s reflexes), but the pose’s theatricality makes it seem like a joke. As observers, we begin to root for legitimate fouls not to be called. We root for the rules to dissolve. We begin to root for cruelty.

A friend of mine once had a theory that everyone’s personality could be expressed as a balance between two Peanuts characters. A corollary to this was that everyone thought they were part Snoopy, but almost no one was. Snoopy is the irrepressible id of the strip, conscious of the misery around him but lifting up its edges to find the joy underneath. It’s a very rare quality!

According to my friend, I was part Schroeder and part 5. 5 is a very minor character—if you have any mental image of him, it’s probably of the fluid, back-and-forth head-bobbing dance he does in A Charlie Brown Christmas. In the Peanuts canon, 5 got his name because his father was so upset about numbers in modern society causing people to lose their identities. When Lucy guesses that 5’s name was his father’s way of protesting, 5 answers that, no, it was his way of giving in.

The 76ers are part 5 and, yes, part Snoopy, and they have a chance to shift that balance. Harden and his career-long surrender to joyless, objective technicalities is gone, the Sixers are now guided in part by Tyrese Maxey and his evident delight in playing basketball and his gorgeous smile and his bizarre array of seemingly psychically guided floaters, and they have a chance to be actually fun to watch. Maybe Maxey takes a leap? Maybe Embiid rediscovers his sense of spontaneity? Maybe Patrick Beverley (he’s all Lucy, right?) spontaneously combusts from so much performative villainy?

Jodorowsky writes that the tarot reader should attain “a state of perfect neutrality by ignoring his desires, feelings, and opinions,” essentially becoming a mirror of the subject being read. “The level of the individual’s [the reading subject’s] consciousness,” he claims, “is reflected by the purity of our own mind.”

Besides being half Schroeder and half 5, I’m a 76ers fan and I absolutely do not have a pure mind on this topic or just about any other. The “individual” whose consciousness I’m reading here is a basketball-reference.com page. For this whole exercise, I’m both mirror and reflection, and it’s hard sometimes to separate desire from manifestation. The 76ers will go 55–27 and finish third in the Eastern Conference, then lose in the conference finals.

![]()

Los Angeles Lakers:

Situation: Four of Pentacles

Obstacle: Page of Wands

Outcome: Two of Cups

In a weird way, The Last Dance and the Adam McKay-produced series Winning Time are complementary opposites. While The Last Dance was, quite literally, history written by the winners, great-man hagiography about the ends justifying the means, Winning Time is about the means creating the ends, how enjoying the spoils of victory before the actual victory can, in fact, create an environment in which victory is possible. This means that Winning Time focuses a lot less on actual basketball, which, paradoxically, makes the basketball in it seem to matter a lot more.

That’s because Winning Time is at least partly about the benefits of instability, both on the court and off. By showing how instability runs through the 1980s Lakers, it also shows how the team fit perfectly into the time and place of Reagan-era Los Angeles, with all its stereotypical surface qualities of objectification, plasticity, and conspicuous consumption.

Years later, a self-parodying version of that ostentatiousness defines the Lakers. They’re as much a brand as a team, one defined by both its shameless obsequiousness towards celebrity and wealth and the lies that these are based on (“Forum Blue” is purple! Calling purple blue doesn’t make it blue!). But the thing is, like L.A. itself, everyone seems to know how ridiculous it all is, and that makes it kind of . . . lovable? Even if you hate the Lakers, deep down, you’re probably glad they exist.

But a world in which instability for its own sake is good (even if it leads to flakiness and materialism) requires blind optimism for the future and a belief in the benefits of change for change’s sake. And this is kind of the opposite of the current construction of the Lakers. LeBron, in his twenty-first (!!!) season, is going to keep mixing his preternatural understanding of the limits of space and movement with his physical transcendence of both, but as the game evolves away from him and as Morant and Fox and Jokić and now Wembanyama distort the concepts of space and movement on the court, this transcendence keeps seeming more and more limited. Anthony Davis, who somehow seems like a vestige of some bygone era even though he’s only thirty, is going to mix brilliance with passivity for half a season and then fuck up his knee.

The rest is tinkering around the edges. D’Angelo Russell is the NBA’s Justine Sacco, still haunted by the stain of something stupid he posted on the Internet once, to the point that it seems possible that Nick Young’s dislocated soul is whispering in his ear, telling him to miss defensive rotations. Christian Wood seems like a jerk.

We know the beats of this plot. Its rising action is plagued by inertia.

The stranger who came to town—the potential for excitement and inconstancy—is Austin Reaves, who’s basically a jock version of Axl Rose at the beginning of the “Welcome to the Jungle” video, going straight from the Greyhound station to the Forum without bothering to take the sprig of wheat out of his mouth. There’s a compelling incongruity to a meming bumpkin trying to cleanse the team’s collective chakras, but there’s certainly nothing glamorous about it.

The Lakers will go 42–40, finish eighth in the Western Conference, and lose in the play-in.

![]()

Milwaukee Bucks

Situation: The Magician

Obstacle: Four of Cups

Outcome: The Emperor

It’s a shame, but Giannis Antetokounmpo’s game never ascended to complete freakishness and instead became a methodical and repetitious array of baby hooks and layups, with maybe a shocking, teleporting Eurostep thrown in to remind you of what might have been. Damian Lillard’s kind of like Keira Knightly to Steph Curry’s Natalie Portman—different but also basically the same, and a little bit worse. Together, they’ve got the potential to bring out the weirder angles of each other’s game (point Giannis outletting to Dame for a pull-up forty-footer! No-look alley-oops where Giannis leaps from the foul line!), but that potential won’t be fulfilled. There’ll be growing pains and they won’t be amazing defensively, but scoring points will probably be so easy for Milwaukee that they won’t really have to be anything too wild.

The Bucks will go 60–22, finish first in the Eastern Conference, and win a fairly joyless NBA championship. Let’s move on.

![]()

Boston Celtics

Situation: Knight of Wands

Obstacle: Ten of Swords

Outcome: Three of Pentacles

Describing the observer effect in quantum theory, the Austrian physicist Heinz Von Foerster wrote, “‘Out there’ there is no light and no colour, only electromagnetic waves; ‘out there’ there is no sound and no music, only period variations in air pressure, ‘out there’ there is no heat and no cold, only moving molecules with more or less mean kinetic energy, and so on. Finally, for sure, ‘out there’ there is no pain.”

Essentially, we create our world and construct everything in it, and we do so through comparisons—our brains performing a trillion subliminal rankings every instant, rankings that not only help us decide whether or not to wear a coat when we go outside, but that create the coat, and outside. Nothing exists without you and me.

The standard narrative is that Jayson Tatum and Jaylen Brown are like partners in an 80s cop comedy—the mercurial one and the cerebral one—or they’re depicted like they’re within a mortal Jordan/Pippen framework where Tatum’s the natural scorer and Brown’s there to fill in the cracks with sticky defense and supplementary scoring. Of course, the way this story goes is that Brown’s going to chafe at this arrangement.

But the thing is, what if the reductive narrative framework that causes Tatum and Brown to exist relative to each other is just that: a narrative construct? Tatum and Brown have become all-around menaces in multiple facets of the game, but each seems to have somewhat fatal flaws—Tatum’s strange, creeping passivity, Brown’s self-conscious and at times misplaced assertiveness. It’s as though they’re pushing against the story being told about them, but the mechanics of it are already in place. The ending can’t be changed.

One of the consequences of quantum theory is that two systems that have interacted once are thought to be inextricably bound forever—if one is observed, and therefore changed, an equivalent change will take place, faster than the speed of light, in the other. If the Tatum/Brown pairing is fundamentally disordered, then every other move the Celtics make (and swapping out Marcus Smart and Robert “Time Lord” and Grant Williams for Jrue Holiday and Kristaps Porzingis are huge changes!) is irrelevant—they’re charging ahead without the potential for this group to cohere into a meaningful shape and structure.

The late mad-scientist biologist Lyall Watson believed that the mechanics of the permanent, instantaneous, universe traversing link between systems might be the same as those that enable clairvoyance. The Celtics will go 58–24, finish second in the Eastern Conference, and lose in the conference semifinals.

![]()

Phoenix Suns

Situation: Ten of Swords

Obstacle: Seven of Wands

Outcome: Three of Pentacles

Talking about quantum mechanics in the service of mysticism diminishes both. Obviously, even the most theoretically minded scientific study doesn’t hold with a discipline that rejects repeatability and verification in favor of anecdote and intuition, but it also demeans the metaphysical to make it sidle up to science hoping for a pat on the head. The mystical has nothing to prove to anybody. That’s the whole point.

This unprovability, of course, has always made metaphysics a refuge for bald-faced hucksters. If you’re anything like me, you’ve probably seen a few of your more esoterically minded friends pulling the cheap threads of a right-wing spiderweb around themselves over the past few years. There’s an old horror movie called Blue Sunshine in which late-70s proto-yuppies turn into homicidal maniacs due to long-delayed effects of acid they took in their younger, more idealistic hippie days. I think about Blue Sunshine a lot now, wondering if it somehow predicted the coke that apparently went around Williamsburg in the mid-aughts that, fifteen years later, made its users easy prey for colloidal silver pyramid schemes and meme versions of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

But if you’re in desperate need of guidance from forces we can’t measure (and who isn’t), how can you tell the shamans from the frauds? The answer is that you can’t. Though most frauds aren’t shamans, most shamans have an element of the trickster, if not the outright fraudulent, to them. This is a feature, not a bug; the entry point to defying the binary logic upon which the material (and technological) world is built, and comprehending the overlapping, entropic vibrations that can unite opposing ideas into a single contradictory truth.

Basically like quantum mechanics.

Anyway, the Phoenix Suns are like the paired and instantaneously linked particle to the Celtics—a team that made big swings in the offseason to find out if there’s a fundamental disconnect in the interaction of their two stars. Their similarities are only in the measurable, traceable elements (like the scores of basketball games), but where the Celtics will feel stagnant, the Suns will have joy running through their hearts as Devin Booker and Kevin Durant actually seem like they’re enjoying themselves, go 58–24, finish second in the Western Conference, and blithely lose in the conference finals.

![]()

New York Knicks

Situation: Five of Swords

Obstacle: Page of Cups

Outcome: Page of Wands

One of the things that can be wonderful about New York is that it’s a place where contradictory binaries can unite, where unprofitable artistic strangeness flourishes despite the city’s essential economic cruelty. In basketball this has historically manifested in a stereotypical string of point guards who couldn’t perform the one essential basketball skill of shooting the ball into the basket, players for whom the game, mystifyingly and wonderfully, was about something else.

For a long time, the only video online of God Shammgod’s eponymous in-and-out dribble was a grainier version of this one. The announcers don’t notice what’s happening. Shammgod badly misses the shot at the end. It all seems so inconsequential.

But someone recognized this moment and captured it. They held it up to the light and said, hey, this might not seem like much, but actually, it’s wonderful.

God Shammgod flamed out of the NBA in twenty games, shooting 33 percent.

His name really was God Shammgod—a way too on-the-nose moniker that condenses the same shaman-huckster binary that undergirds popular metaphysics to three syllables.

Something’s happened that doesn’t happen to the Knicks that often, and as far as I know, has never happened to a Tom Thibodeau-coached team—they’re a joy to watch. Thibodeau, who was apparently made flesh from parking-lot gravel like Aphrodite from sea foam, has famously run his teams into the ground playing his stars incessantly while he yells out complex defensive instructions from the sideline in the form of different inflections of the word “ice.” But somehow these Knicks play with a looseness that belies Thibodeau’s meticulousness. At times the team’s internal balance manifests between players, as when Jalen Brunson’s steadiness tempers Julius Randle’s mercurial spontaneity, but at other times you see the balance in one individual’s game, as when Immanuel Quickly (whose name sounds like it was invented by the same hack novelist who named God Shammgod) somehow seems on the verge of falling over or levitating with every step.

Having so many good players who are also a little too incomplete to be great also means they’re freed from expectations. No one really expects the Knicks to win the championship. They’ll make the playoffs, sure, and maybe win a series or even two, but even Knicks fans, who, in my extensive experience, are absolutely delusional in any given year about the quality of their team (I was a bartender in New York for a long time, and the frustrated slaps of Knicks fans on a wooden bar top has a particular timbre unlike any other), seem to understand this. Pleasure in strangeness is the point, an element that’s been missing for the Knicks since the weird, “Expendables”-like Carmelo-Rasheed Wallace-Tyson Chandler team from a decade ago.

Sometimes joy and strangeness add up, improbably, to material success.

The “Shammgod” is now a known part of the ballhandling vocabulary of Chris Paul, Kyrie Irving, Steph Curry, and just about any kid who watches YouTube dribbling tutorials.

That geriatric 2012–13 Knicks team drafted a thirty-five-year-old and won fifty-four games.

Once in a while, New York will offer a Madonna or Basquiat to the world, strangeness which aligns with larger forces not only to make money but to transform mass culture. Madonna and Basquiat are important geniuses, but sometimes the city also offers us Arthur Russell or Harry Smith or a dancehall show in a roller rink where someone plays the sleng teng riddim on a didgeridoo—smaller pleasures whose influence, if it ever comes to fruition, is delayed and the profit ethereal, not material.

So which is the god and which is the sham?

The Knicks will go 53–29, finish fourth in the Eastern Conference, and lose in the conference semifinals.

![]()

Denver Nuggets:

Situation: Knight of Cups

Obstacle: The Lover

Outcome: Queen of Swords

Per James Naismith’s original rules for basketball, if a player had control of the ball, they couldn’t move. The only way to advance the ball was by passing. The thing is, this never really changed.

Though dribbling is now codified, it evolved from a purposeful, specific bending of those original rules. Someone said, “If I can’t move while I control the ball, I’ll never put two hands on it, and therefore never be in control of it.”

And this smart-assery was rewarded, not punished. That the game actually evolved to turn this mild form of cheating into a sanctioned and essential skill speaks to how creativity was folded, from the start, into basketball’s essence. True innovations in the game don’t usually come from a coach creating a new defensive scheme or a method of developing specific skills; they come from the bottom up, from players trying things out that may or may not end up actually mattering to the score.

Witness Luke Kornet jumping from comically far away when an opposing player shoots. Witness Rasheed Wallace loudly analyzing human inequity aversion. Witness young JaVale McGee getting called for yet another goaltend after joyously volleyball-spiking a descending shot into the stands. Witness Rajon Rondo’s collection of tics and rituals in his entire glorious, possibly neurodivergent career. Witness LeBron and, yes, that stupid windmill. Witness Pete Maravich. Witness God Shammgod.

Nikola Jokić is the apotheosis of this, the developer of a uniquely functional game that seems pieced together from a million creative and funny dead ends, with the Nuggets’ championship win last year validating this kind of creativity. If you want to be reductionist about it, it was also a repudiation of the “Kobe mindset,” which valorizes endless work as the goal, not the process. Jokić understands that basketball is just a game, even if it’s a lot more than that, too. At the podium after the Nuggets’ win, Jokić answered a softball question about whether he was looking forward to the championship parade by saying, “It’s not the most important thing in the world. There is [a] bunch of things that I like to do.”

There’s a part in the recent Robert Glück interview in The Paris Review where Glück says, “It seems to me that the story of Oedipus is told from the wrong point of view. It’s Dad who wants to murder the son. Dad controls the narrative, and since he can’t think this forbidden thought, he projects it onto his child.”

There’s something that rings deeply true to me about this, and not just as a parent of a wonderful and creative and maddeningly stubborn child (attention, CPS: upside-down smiling-face emoji). The things we make—our children and our creative works—have a way of spinning away from us. They take on their own momentum, their own consciousness, and the equilibrium between control and freedom is really difficult to find. And succeeding once might not help in the future; it might calcify the process into one of execution and repetition, rather than discovery.

At the same time, if you let go of everything you’ve learned, then you don’t know anything.

The thing about Nightmare Alley’s fraudulent reading that fits everybody is that it’s also, at least in the novel, absolutely accurate. Stan’s dog and his relationship with his father are essential to the weaknesses that lead to his descent.

So is creativity the product of individual expression or of tapping into the universal and framing it as something new?

I’ve been telling my son “Adam and Sophie” stories almost every day for a couple of years now. Adam is my son. Sophie is our dog. In the stories, Adam and Sophie are superheroes who, in their secret identities, drive an ice cream truck. Every day, my son describes the story he wants to hear. A little while ago, I realized how he’d internalized ideas of contradiction and complication when he told me that he wanted a story about “a bad guy who does bad stuff because he thinks he’s doing something good.”

Charles Schulz said of 5’s father’s decision about naming his son, “His kid has got to suffer . . . but kids learn to ride things out.”

One thing I’m learning about parenting is that I’ll almost certainly mess my kid up in ways neither of us understands for a long time. All I can do about this is give him the tools to possibly turn that heartbreak into something strange and beautiful.

The Denver Nuggets will go 62–20, finish first in the Western Conference, and lose in the NBA championship.

Liam Baranauskas is writer from Philadelphia.

More sports