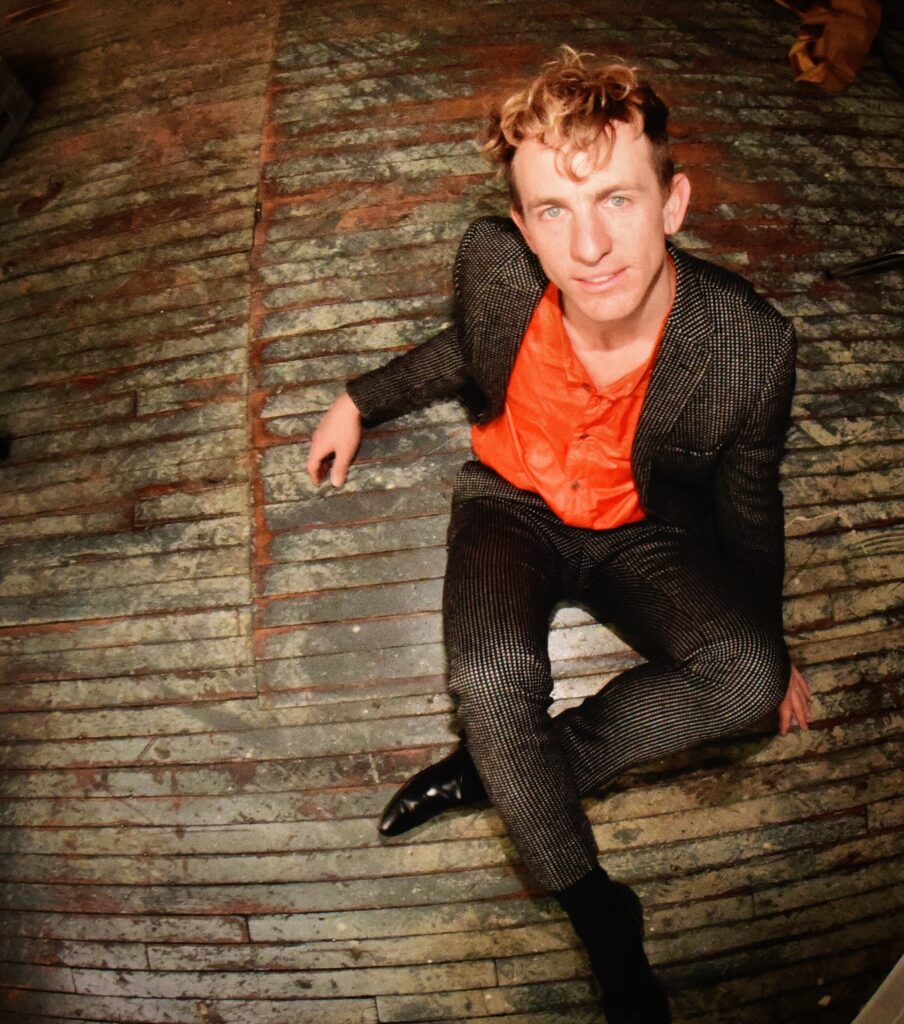

The Guest List | Buck Meek

music

The Guest List is a regular book column that surveys the reading habits of our favorite musicians. In this edition, Jimmy Cajoleas talks with the Texas-born singer-songwriter Buck Meek. His latest album, Haunted Mountain, was released in August.

Jimmy Cajoleas: Your press release mentioned that you got to read Judee Sill’s personal journals. She’s one of my heroes.

Buck Meek: She’s one of my heroes too. These filmmakers [Andy Brown and Brian Lindstrom] made a documentary about her recently and they had access to her journals. They had originally sent me photocopies of about fifteen or twenty pages, mostly unfinished songs and lyrics, and they asked me if I would be interested in putting some of them to music. The one I connected with the most was what I later learned to be the very last entry in her journal. It was dated just a few weeks before Judee passed away, an unfinished song with unstructured lyrics. She’d mapped out the rhyming scheme and scribbled a few rough notes on the page, but it was really moving knowing it was written so soon before her death, and it was dedicated to her ex-boyfriend and his daughter, who she was very close with. I put a melody and chords to that and restructured it to fit a song form that made it on the album, called “The Rainbow.” It was an honor.

JC: Were the notebooks mostly lyrics, or were there stray thoughts and things like that in there?

BM: The photocopies they sent me were mostly lyrics. I think they had gone through and plucked out some unfinished songs or completed lyrics with no sheet music or melody yet. But there were a lot of ideas written in the margins, questions and journal entries, meanderings. Once I finished the song, the filmmakers invited me to a recording studio in Los Angeles, and they brought the actual journal and I was able to flip through that. There were a lot of journal entries. I only had a minute to flip through hundreds of pages, but that was pretty wild.

There was one page that was really incredible for me to see. I’ve always felt that Judee has this relationship with harmony and composition in synthesis with her lyric writing. She really understands the emotional impact of harmonics, the different moods and the subtle emotional impact of all the complex harmony, beyond the major and minor and into the seventh and the ninth and the eleventh and the thirteenth, all the tensions there. And in the journal there’s a page where she assigns a human emotion to every harmonic interval. It was astonishing.

JC: Are you reading anything right now?

BM: I’ve been on tour for two and half months. I used to bring like five books on the road, but lately I’ve been trying to travel really light. Most of the time, if I have a free moment, it’s easier to read short stories or poetry. I brought a W. B. Yeats collection of poetry this last tour. It was easy to work through that, read a poem in the morning sometimes.

JC: You’ve previously recommended people read Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy and Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History by S. C. Gwynne, together at the same time. Can you tell me a little about that juxtaposition?

BM: I grew up in the Texas hill country, in what was once partly Comanche territory. Weirdly, I grew up in Hays County, named after Jack Hays, who is one of the Texas Rangers mentioned in Empire of the Summer Moon. He helped develop the six-shooter, which played a major part in the eventual demise of the Comanches.

The Comanches are incredible. They were one of the last tribes to keep their territory intact, and they had this immense amount of land in Texas and New Mexico and Oklahoma, and the Great Plains. It was almost impossible to track them out there because it was so vast. Of course, in Blood Meridian, the Tennessee kid falls in with this group of scalp hunters who have a handful of run-ins with the Comanches. Empire of the Summer Moon provides a lot more context. I feel like the two books go hand in hand, telling two very different sides of the same story.

JC: What attracts you to Cormac McCarthy?

BM: One thing I really love about his writing is his relationship with the flora and fauna of the world. Blood Meridian, for instance, is the most brutal book I’ve ever read. It’s just constant violence from the beginning to the end. It’s a critique of manifest destiny commenting on the idea that violence is inherent in all humans. It’s unrelenting. But there’s this element of observation into the flora and fauna of the West. Like the Judge, the leader of the scalp-hunting gang—definitely an evil character. He’s a quasi-biologist, taking constant notes about the plant and animal life they encounter, observations of unknown species. I take that as an analogy for colonization, a need for dominance over nature that exists in a character like the Judge. He’s the most educated of the bunch. The rest of the gang are mostly criminals without much formal education, and the Judge has this understanding of mythology, religion, and history, and he uses that to constantly manipulate everybody. I think Cormac McCarthy uses the Judge as an avatar for detailing nature. At the same time, those passages provide a respite from the violence, and maybe illuminate some of the incentive for survival, even in the midst of war and brutality. The book is pretty much a hellscape, and when I read it, I ask myself what these people are fighting for. The juxtaposition between nature and the humans shed some light on that for me.

JC: Most of the writers and artists we’ve talked about here have a very particular relationship to mysticism. What about that quality draws you to certain writers?

BM: I love the thin line between history and mythology, religion and mythology. That threshold is really fascinating to me. Another one of the books I wanted to talk about was The City and the City by China Miéville. The basic idea is there are two cities kind of interlaid over each other in the same geographic space, with two societies, and the inhabitants are born into one or the other. They’re required to consciously unsee the other. I was talking with my wife about it this morning. She’s reading a book by Lawrence Blair called Rhythms of Vision. In this book Blair’s talking about Magellan; when he landed in Tierra del Fuego, the Fuegian people weren’t able to see the ship in their account. Regardless of the ship’s huge bulk, the horizon remained undisturbed. I love this idea that seeing something always involves unseeing something else. Our perception is filtered, I think, our minds filtering out competing stimuli. There’s a bias. Maybe that bias is necessary for survival, or for our social identity. I’m fascinated by that in terms of our relationship to mythology as well.

JC: Do you have any books you return to?

BM: A more recent book, George Saunders’s A Swim in a Pond in the Rain is one I feel like I will read forever, over and over again. I’m on my second reading now. It feels like a companion that I’ll keep with me for sure. There are so many lessons in there. I reread every chapter about three times before I would move on. It has really enhanced my relationship to reading. I love how playful he is, how much he uses conversational language, and how he uses his humor to prove his points.

JC: Did you grow up a reader?

BM: Very much so. Both of my grandparents on my mother’s side were professors of literature. My grandmother got her PhD in Shakespearian literature and her master’s in Greek mythology. She would read a whole book in a matter of hours every day. My grandfather had his PhD in Faulknerian literature and mostly taught Faulkner at Tulane. So I grew up with them constantly talking to me about books.

I just inherited my grandfather’s entire Faulkner collection. He had everything Faulkner ever wrote, including his journals. I just moved it into my house and I’m going to start reading that next. I guess that’s where my love for Yeats came from. My grandmother would read me Yeats as bedtime stories.

JC: Yeats is so amazing because you have his explicitly political poems, the more mythological ones, and some that are so physically concrete, about his friends and about aging.

BM: I love writers like that, who are pulling from multiple disciplines. I prefer mythological influences that aren’t exclusively mythological. Using it as a device but having the context of other disciplines. I feel like they empower each other.

JC: Another book you’ve mentioned in the past is Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes.

BM: On tour, when I don’t have time to read, I’ll pick up my camera and walk around the city taking pictures. The thing in that book that made the biggest impact on me as a photographer was the idea of the punctum, the one element of the photograph that creates this friction, something that is surprising or ugly and catches your eye in an oblique way. That really transformed my relationship with photography, and writing too.

JC: Do you see an analogue for that concept in music at all?

BM: Totally. I related to that idea so much coming from music. The more I write and the more I record, space has become really important to me in music, being intentional and efficient about what you add to the song. Working with the producer Andrew Sarlo for the first four Big Thief records, he was constantly reminding us that if we were going to play or overdub anything it had to be absolutely essential, never for decoration. Only adding something if it really changed the direction of the song, adding a whole dynamic that wasn’t already there, or if it was essential, reinforcing some other element. To me that kind of relates to the punctum, finding a piece of the song that changes people’s perception of the whole. Providing some friction or context. It works the same with lyric writing.

JC: Did growing up in Texas ever influence your reading choices? Is a sense of place important?

BM: My grandfather was a sixth-generation Texan and my grandmother was fifth-generation. My family’s been there for a long time. I feel this essential relationship with Texas. I grew up in a small town called Wimberly where a lot of the outlaw songwriters live, like Butch Hancock from the Flatlanders and Ray Wylie Hubbard. I was always surrounded by these incredible songwriters. One thing I love about that outlaw genre is there’s a lot of mysticism, like in Townes Van Zandt, and a lot of darkness. And so that had a big influence on me as a writer and a reader.

It wasn’t until I left Texas at seventeen that I started reading Western novelists, like Cormac McCarthy and Larry McMurtry. I think it was a way to feel closer to the home that I left as a teenager, to cure homesickness. As a kid all I wanted was to escape. But my identity as a Texan really formed after I had left and was able to admit to myself that’s where I come from. I think the separation from it helped me cultivate the things I love and release the things that I don’t relate to or don’t love. I have a healthy relationship with Texas in the distance. When I go back there, I have a more intentional relationship to it. Those books really helped with that.

Jimmy Cajoleas was born in Jackson, Mississippi. He lives in New York.

More music