The Costs of Paying Attention

Reviews

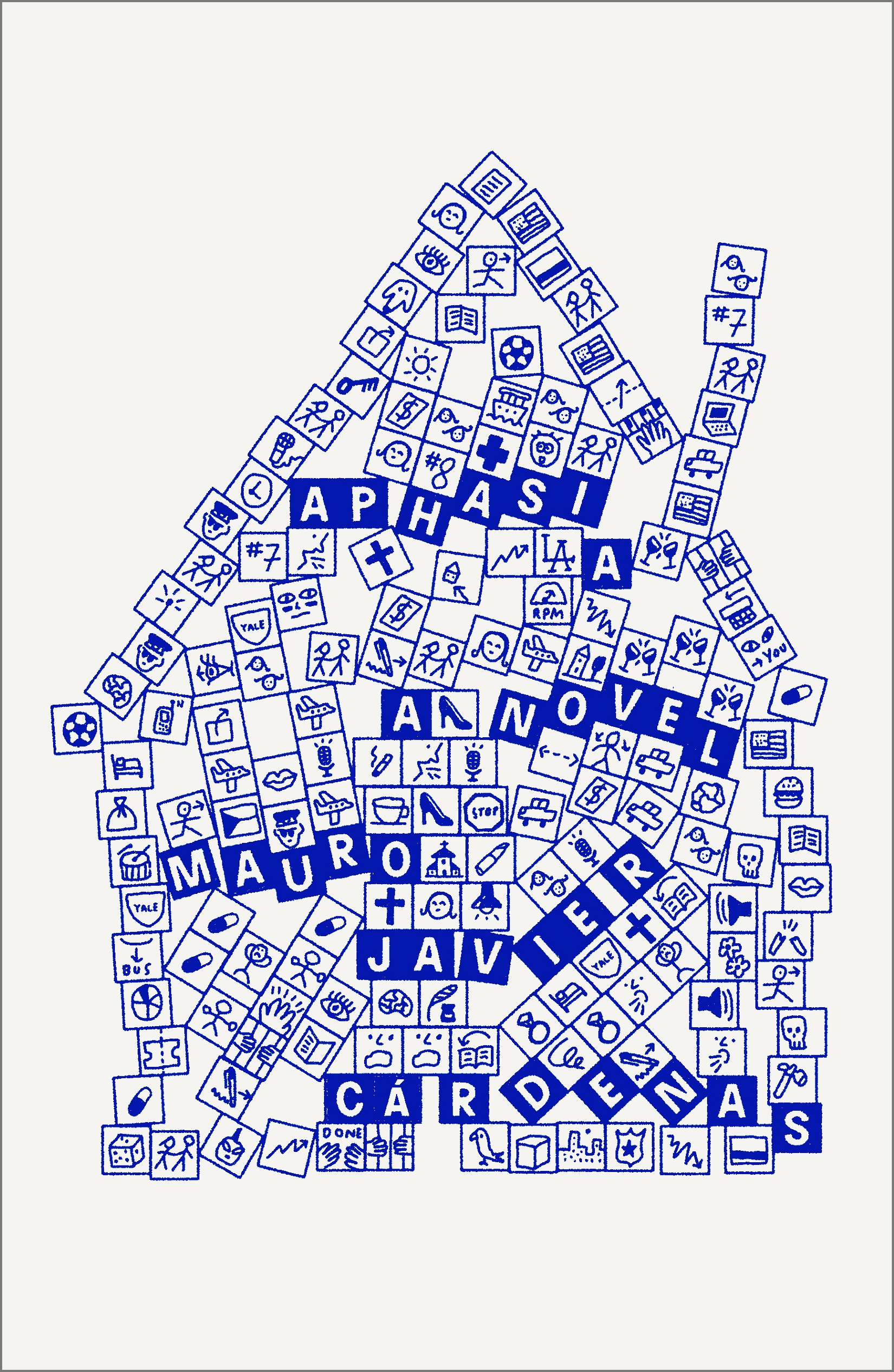

By Wilson McBee

As I write this review, a swarm of thoughts is buzzing around my brain. Nearly all of them are completely unrelated to the subject at hand, Maurio Javier Cárdenas’s second novel, Aphasia. Worries about the current president’s refusal to concede the election bump against fears of how my six-year-old and I are going to survive another six months of virtual kindergarten; a digestion of the ambient guitar rock coming through my headphones, Ezra Feinberg’s Recumbent Speech, contends with backstage escapades recalled in Trouble Boys, a biography of the Minneapolis band the Replacements I have just finished reading. Yet I proceed, not muting these pestering mental intruders as much as I am trying my best to ignore them.

The state described above is one that Aphasia embraces rather than denies; further, it seeks to capture it on the page. It has been a hundred years or so since the term stream-of-consciousness was first used to describe attempts to mirror the workings of the mind. And while it would be impossible for Cárdenas to completely avoid the drift of Old Masters like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, his closest touchstones are of more recent vintage: the monologic rants of Thomas Bernhard and the epic, serpentine sentences of László Krasznahorkai loom large. Combining these influences, Cárdenas might be said to be writing in streams of consciousness (note the plural), in which threads are woven in an often-dazzling performance akin to a DJ’s mashup, in which two different songs can be heard separately as well as together.

Cárdenas centers Aphasia in the thoroughly distracted mind of a struggling novelist named Antonio. An immigrant from Colombia, Antonio has recently separated from his wife, with whom he has two young daughters, although they all still live in the same apartment building. Meanwhile, he tries to maintain a day job at a financial services firm and worries over the fate of his only sister, Estela, who is on the run from the law after suffering a mental breakdown. As he revisits the events of his life, Antonio interrupts himself with asides, questions, and literary references, which are themselves beset by further intrusions. The result is a fragmented narrative marked by the liberal use of em dashes and parentheses, the latter used to capture this nesting-doll effect of thoughts embedded within thoughts embedded within thoughts. (Because Cárdenas’s constructions are so long and convoluted, with single sentences running across multiple pages, quotations of only a few lines fail to do the book justice. To get the effect, imagine I interjected something here about how the mnemonic “Days of the Week” song, a parody of the Addams Family theme (There’s Sunday and there’s Monday, there’s Tuesday and there’s Wednesday . . . ”), played by my son’s teacher reminds me of a similarly recursive moment from Feinberg’s album, which itself borrows from Steve Reich’s “Eight Lines,” discussed by Antonio in Aphasia.) An irony of this style is that as it seeks to portray a mind frazzled by emotional stress, it demands nothing less than the complete focus of the reader. Fail to notice a reference to a film Antonio mentions having watched recently, for example, and you will be at a loss when, a couple of pages later, Antonio summons the protagonist of that film in making a comparison to his own life.

Suspicious of his own memory, Antonio likes to record interviews with people with whom he has been close. Sections of Aphasia reproduce these recorded conversations as Antonio listens to them while making notes to himself in response. In conversations with his mother, Antonio learns about her complicated upbringing in Colombia, in which she stayed in the country after her parents immigrated to the United States. These talks also lead Antonio to revisit his own difficult childhood, dominated by his abusive father, whose behavior eventually pushed Antonio’s mother to take her children and join her parents in America. In addition to the obvious pull of nostalgia, Antonio is drawn to these memories because he hopes they will help him understand the two crises that dog his existence, his sister’s mental illness and the breakdown of his own marriage.

Both Antonio’s father and his maternal grandfather were womanizers; Antonio’s own philandering, in addition to his general resistance to settling down, led to the breakup between him and his wife. Among the other interviewees are former girlfriends and women Antonio has met through an online dating service. Antonio probes them into divulging their personal histories (many are immigrants themselves), much like a psychiatrist or an oral historian. In so doing, he comes off as a cross between a lothario and a hopeless romantic. He’s drawn to these women less out of sexual compulsion than out of a desire to disappear into their lives in the same way that he disappears into books or movies. Regardless, one still gets the sense that he’s using them. Likewise, Antonio feels like an interloper among the members of his family. He reflects at one point on “this family of his, which, amazingly, still includes him,” as if he can’t quite believe that they keep allowing him to come around. Cárdenas’s deft characterization of Antonio’s confused, troubled masculinity is one of the novel’s most impressive achievements.

Narratively, the book’s most compelling sections are the ones dealing with Estela. Once a successful actuary at an insurance company, Estela suffers from a series of increasingly alarming delusions—suspicions that her coworkers are conspiring against her devolve into full-blown paranoia involving Obama and the CIA transmitting messages to her through devices implanted in her ears. Here Cárdenas applies his unusual style to a conventional intrafamily drama, as Antonio and his mother deliberate over whether to commit his sister to a mental institution against her will. In the course of these discussions, again harkening back to the past, Antonio discovers a family secret that sheds a new, tragic light on Estela’s problems as well as his own.

It turns out that family is both the cause of and the solution to Antonio’s problems. In Aphasia as in last year’s National Book Award winner, Susan Choi’s Trust Exercise, trauma has an ability to affect the future as well as twist our understanding of the past. In other words, characters are molded by certain events so much that they can’t fully comprehend them; trying to recover the truth of what really happened is easy as staring straight at the sun. Antonio relies upon the recollection of others while denying his own memories and indulging in the pinball-like movements of his mind. Estela, to say the least, has it much harder. Under these harrowing and yet all-too-common circumstances, getting a grip on what is happening inside your own mind constitutes an act of real courage.

Wilson McBee is a staff writer for SwR.

More Reviews