The Guest List | Ryan Davis & the Roadhouse Band

music

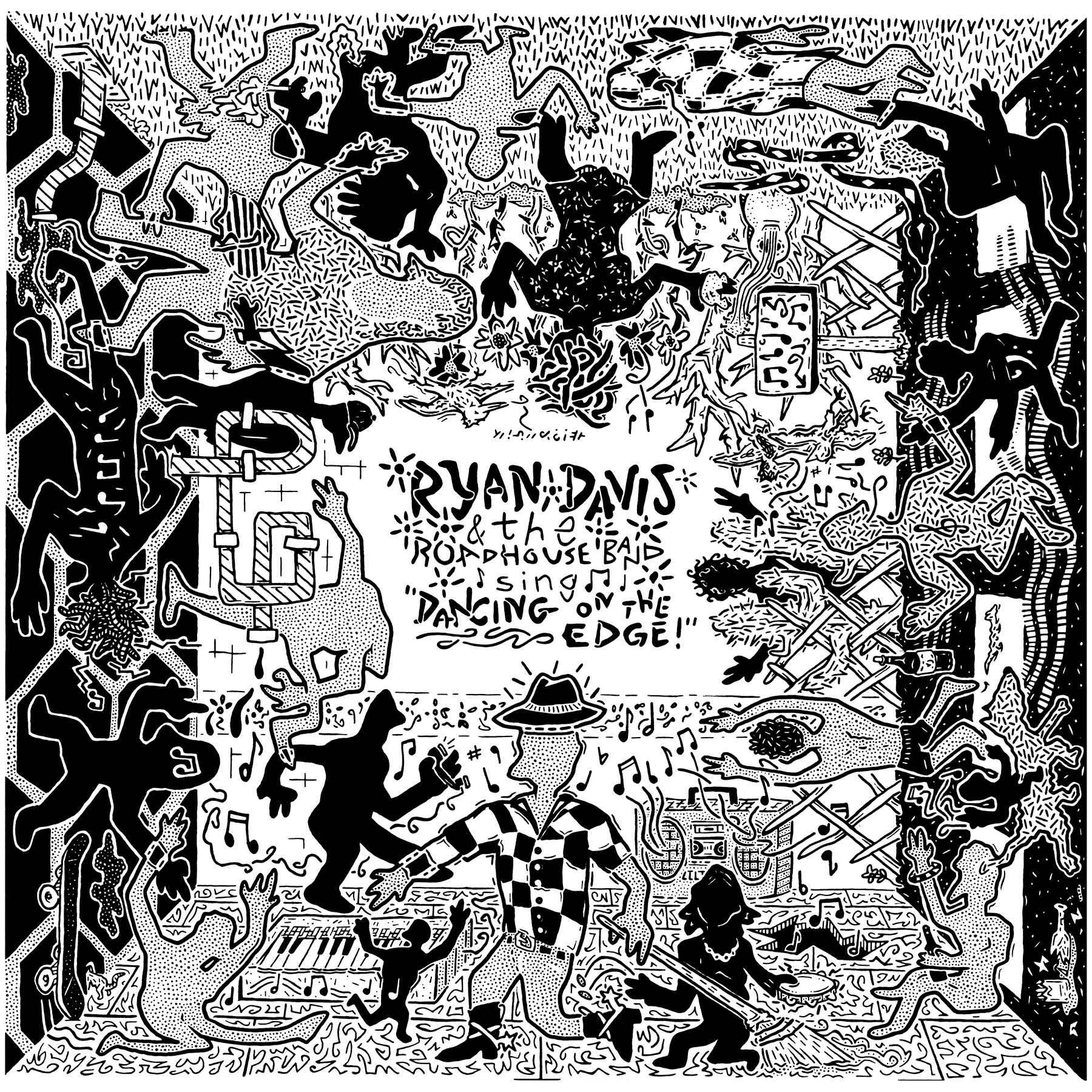

The Guest List is a regular book column that surveys the reading habits of our favorite musicians. In this edition, Jimmy Cajoleas talks with Ryan Davis, frontman for the critically acclaimed Louisville band State Champion and, most recently, Ryan Davis & the Roadhouse Band. Their new album, Dancing on the Edge, was released in October.

Jimmy Cajoleas: What are you reading right now?

Ryan Davis: The short answer—as in what I read most recently and most actively on planes and in airports—is A Childhood: The Biography of a Place by Harry Crews. I’ve dug Crews in the past and I’m sure, if one tried, one could probably find influence of that in my songwriting, but I hadn’t read this one before. We were in Omaha a couple months ago, playing a show at my friend and fellow underground-music mover-and-shaker Simon Joyner’s record store (Grapefruit Records, highly recommended if you’re ever in the area!). His wife Sara helps run this amazing bookstore right around the corner called Jackson Street Booksellers, which has been around since the early ’90s. It’s the kind of shop where books are stacked floor to ceiling throughout various nooks and side zones—horizontally, vertically, on the ground, on top of the shelves. I find that places like this usually feel too overwhelming to make for a pleasurable shopping experience, but it was just organized enough to where I was fully engaged with the hunter-gatherer instinct that a good book or record shop can summon in me and I didn’t want to leave. Anyway, I found a copy of this Crews book there, among other things. I’m spending a lot of this month in the Georgia-Florida region, so it felt like the appropriate time to dive in. It’s a really great memoir that acts as an origin story for one of our great literary underdogs while humorously examining the day-to-day calamities of a rural upbringing in the Great Depressed American Southeast.

The long answer, however, is that I was reading more than I ever had in my entire life for the two to three years leading up to COVID. Once the pandemic hit, with all the communal uncertainties and shattered routines and 2020 election cycle/world news and internal/interpersonal chaos that ensued, my desire and ability to focus on reading almost anything of actual value came to a screeching halt. I had just finished Pynchon’s V. at the start of 2020, which I really got a lot out of in terms of stirring some creative juices of my own. I was attempting to read Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death next (which, you know, isn’t exactly a laugh-a-minute page-turner), and I just remember every time I went to read it, or any other book for that matter, I simply could not find space in my brain for it. I wasn’t absorbing anything. You’d think all the extra alone time would have had the opposite effect, as I did find more focus for other practices in my life around then, but reading became harder and harder and honestly kind of stayed that way for a while.

I’ve just begun coming out of it over the last year or two, but now I have this problem of starting too many books at once to where it’s hard to actually finish any of them. I’m in the middle of probably five or six different books right now, at the very least. This isn’t a good thing for me. I blame a lot of it on touring/traveling more frequently lately. Finding cool book and record stores on the road is a perennially stimulating way to spend a free hour in an unfamiliar place, so I’m always picking up new books and peeling through a few chapters when I find a rare moment of downtime. Next thing you know, I’m actively trying to chip away at this looming stack of random shit I’ve purchased on a whim and it’s virtually impossible to find the time for all of it. I’m really trying to prioritize a return to intentionality though. Those few years where I was clicking into gear and comprehensively blazing through books, it inevitably had to have fed a lot into my own writing.

Refusing Heaven by the poet Jack Gilbert is another one I read a lot of on this most recent trip. I was a big fan of his book The Great Fires many years ago, but for whatever reason I don’t think I ever sought out any other collections of his work. I recently came across this one (again, at a bookstore while on tour) and am enjoying it so far.

JC: What are some books you return to over and over again?

RD: One book that I’ve found myself reading every four or five years since college is Air Guitar by Dave Hickey. It’s a perfect intersection of high-art intellectualism and commonplace pop culture Americana, masterfully written with a wide-eyed salt-of-the-earth charm and grit that doesn’t require an MA in critical studies to appreciate (even though it ultimately does come from a place of academia). “A Glass-Bottomed Cadillac,” written in first person by a posthumous Hank Williams, is an especially evocative favorite from that one. I seem to get something new out of reading Hickey’s essays every time I return to them.

Other books I circle back around to from time to time would have to include How Late It Was, How Late, James Kelman’s idiosyncratically busted Scottish-English tragicomedy that chronicles the real-time frustrations of a ramblingly profane yet lovable lowlife. At the start of the book, said protagonist has recently been beaten blind under the blurry circumstances of a several-day bender and is hopelessly resigned to making sense of his newly bleakened reality. I first read it when I was living in Glasgow myself for a semester of art school back in 2005, which just so happened to be the exact same time in my life that I first started writing what would eventually become the earliest State Champion songs. So maybe there’s some embryonic connection to be made there, who knows? The book is honestly a pain in the ass to read at times, but it’s hauntingly funny in its repetitive grimness. It’s almost hypnotic in the way that Samuel Beckett or Thomas Bernhard or Gordon Lish can be, beating this rhythmic, lyrical sense of unending futility into the reader. You eventually become so saturated with despair that you just sort of woozily sway along with the pages. The way I’m describing it doesn’t necessarily sound like an endorsement, but it truly is a brilliantly unique piece of work. Something about it always brings me back.

JC: What (if any) books inspired your new record?

RD: It’s hard to say, honestly. I mentioned V. earlier, which I actually think inspired some of my visual art at the time more than anything else, but there are probably traces of it in my approach to character development (if that’s something I even employ). The two books I most immediately recall reading around the time of putting that record together are Nathaniel Mackey’s Bedouin Hornbook, which I absolutely adored, and Charles Bowden’s Blues for Cannibals. In the early stages of writing the songs, I had scribbled down “Tales from the Ledge” as one of many loose ideas for the album’s name, though it wasn’t a leading contender by any means.

During the recording session, I walked into the studio at one point and overheard my bandmate describe some overdubbed sonic flourish he was attempting as “dancing on the edge.” I think he meant it compositionally speaking, or, you know, mix-wise or whatever. But removed from its intended context, it resonated with me. I continued to think about it with regards to my lyrical content and what I was going through, the things I was struggling with that propelled me to write songs again in the first place. And I had already started Blues for Cannibals at that time, but it wasn’t until I got home from the session that I came across the passage: “My world, the one I appointed myself the official historian of, was the edge . . . the raw, bleeding, throbbing heart of my time was to be found on the edge, not in the center.” Which sort of further activated this feeling that I was already playing around with, and which I ended up quoting on the inner panel of the album jacket. Months later, after the record came out, Allison Hussey wrote about it for Pitchfork and started the review with a quote from Vonnegut’s Player Piano, which read, “Out on the edge you see all kinds of things you can’t see from the center . . . Big, undreamed-of things—the people on the edge see them first.”

I find the topic of inspiration sources to be a very difficult subject matter for me in some ways. One that, on a certain level, almost shouldn’t be discussed at all. There’s something supernatural about it that runs the risk of being critically bruised by over-contemplation, oversimplification. But I do think there was some preexisting psychological pipeline that I was perhaps tapping into, clumsily or not.

JC: Are there music books or books about musicians or artists you recommend?

RD: I briefly mentioned Mackey’s Bedouin Hornbook as it pertained to the last question. I’m not sure how much it influenced my songwriting, if at all, but it’s such a cool book. I loved the sort of letters-as-poems-as-novel excursion through dreamlike spiritual-jazz-underrealms vibe. The main character—and narrator—navigates the streets of this perhaps mutant/alternative America (as bandleader of the loosely Arkestra-esque Mystic Horn Society) by way of cosmic and subcultural musings on such topics as art, musical language (improvisation, collaboration), mysticism, and the human experience. But the book is written in the form of these one-sided correspondences with the mysterious Angel of Dust, whose responses we are never made privy to. So it’s essentially one long, rolling, monological, impressionistic bop from free-floating abstract jive poetry to hard-edged narrative action, depending on the scene. I read where someone once referred to Mackey’s work as “not simply writing about jazz but writing as jazz,” which I think is a very accurate way of describing his style. I just picked up a copy of Bass Cathedral, which is a more recent continuation of the same series, a couple months ago, but I haven’t gotten around to starting it yet.

Other books about music/musicians . . . man, there are so many that come to mind. John Corbett’s Microgroove is a great and informative read, written by a deep head for deep listeners of all varieties. A lot of the Blank Forms publications that have been coming out are pretty illuminating as well, if you’re into more avant-garde-leaning territories. I remember bringing Crystal Zevon’s I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead on a tour with State Champion and Animal City back in the day. It’s not an especially small book, and I don’t think anyone else in the van was even remotely interested in Zevon’s music at that point, but we passed it around over the course of those couple weeks, and by the end of the tour we might as well have started a fan club.

I checked out Greg Tate’s collected essays Flyboy in the Buttermilk a few years back—I recall enjoying that one quite a lot. Oh, and somewhat indirectly related to Tate, there’s a book I bought online in the last year or two called Assembling a Black Counter Culture by DeForrest Brown Jr. This is admittedly one of those that I’ve chipped away at on numerous occasions and have yet to finish, but not for lack of interest. It’s four-hundred-plus pages of ambitiously researched and notated nonfiction, and it’s often so impressively dense that the flow can be tough to ride, but the content is fairly remarkable. I’d encourage anyone with a moderate-to-advanced interest in the evolution of jazz/techno/hip-hop/electro/Afro-futurist urban music to give it a try.

JC: Any other book you’d like to talk about?

RD: In case I haven’t talked about this in an interview before, I would be remiss not to mention that a seminal and formative collection of poetry for me was Zimble Zamble Zumble by the writer M Sarki, then based in Kentucky (now Florida). Mike (“M”) was actually the father of a high school friend of mine, with whom I ran track and wrote graffiti and horsed around after school. That’s how I came to know him. So we’d cross paths here and there, on the weekends, whenever I was over at the house listening to Gang Starr CDs in the basement or whatever. We initially bonded over a mutual love for Wallace Stevens, as I remember it, perhaps Bob Dylan and painters we admired, etc. But Mike quickly saw something more in me as a writer and a thinker and took me under his wing in a way that almost singularly changed the course of my creative life. He himself was a student of Gordon Lish. They had developed a stimulating and uniquely challenging fiction-writing discourse in the mid ’90s, and their working relationship went on to change the shape of Mike’s own creative career.

So it was through him that I first got a glimpse into the world of Peru and Mourner at the Door and Raymond Carver and Thomas Bernhard (whom I didn’t make much of an attempt to gel with until later) and Barry Hannah (whose work I don’t think M actually cared for as much as I did, though it felt in line with the trajectory) and others who either inspired or were inspired by Lish. Gordon Lish was and probably still is the center of Mike’s creative world, in many ways. I think the “Don’t have stories; have sentences” quote could later be applied to my own songwriting, for sure. But Mike was primarily a poet, not a novelist. He encouraged me to pursue my own writing of that nature at an age and at a time in my life when most people saw very little in me, maybe even including myself. He started a little publishing company called Rogue Literary Society with the intent to release a collection of my earliest poems, and he did, as well as works from Barton Allen, Norman Lock, and his own Mewl House.

At that time, I was a quietly sarcastic skateboarder who spent most of his time aimlessly hanging out in parking lots, scribbling in notebooks, knocking stuff over, listening to ’90s East Coast hip-hop and hardcore punk. I got relatively bad grades, I had very few goals, I didn’t take many things seriously, but I was obsessed with music and I liked to write. Mike discovered that in me and showed me everything from Samuel Beckett to early Bright Eyes. This was, what, 1999, 2000? 2001? I still have the Songs: Ohia Mi Sei Apparso Come Un Fantasma CD-R that he burned me my sophomore year. I’d already heard some of Jason Molina’s studio stuff, but that live in Italy set was so mysterious, so enchanting. It had a profound and lasting effect on me. And I want to say that Jason and Mike may have even struck up a friendship of some sort, if I remember correctly.

But as much as any of these things, the influence of Mike’s own writing and the encouragement he provided to me on a personal level is something to which I will always be indebted. Zimble Zamble Zumble was the first time I read him (I actually just read it again the other day, in fact), so it’s forever the one that lit a match in my young brain, but everything he does is criminally underknown. I’m biased, of course. I really do feel like his work is deserving of a wider audience though. If I can use this opportunity to express that, well, give the man his flowers!

Jimmy Cajoleas was born in Jackson, Mississippi. He lives in New York.

More music