“A Grave Moral Mistake”: The Tragedy of P.G. Wodehouse’s Berlin Broadcasts

Interviews

By Elizabeth Nelson

Forty-seven years after his death on this day in 1975, it remains one of the great literary scandals of the ages, an incident that reverberated throughout Europe and the United States and very nearly permanently cost one of the most beloved practitioners of English letters his reputation. In 1940, the treasured British humorist P.G. Wodehouse found himself on the wrong side of history when Nazi Germany invaded France while Wodehouse was residing in a comfortable French coastal town with his wife Ethel, their dogs, and their parrot Coco. He was eventually interned in a series of German camps throughout Europe before being compelled to record a series of radio broadcasts by the Nazi high command. These transmissions were specifically intended to capitalize on Wodehouse’s enormous popularity in America in order to pacify the growing sentiment that the U.S. needed to enter the war and help combat the rising threat of Nazism.

I’ve always loved Wodehouse. The best of his writing has been a tonic to me on my saddest days, and I would while away hours watching televised adaptations with my dad who recently passed away. And yet this episode has always troubled me, as indeed it did my father. What was Wodehouse thinking?

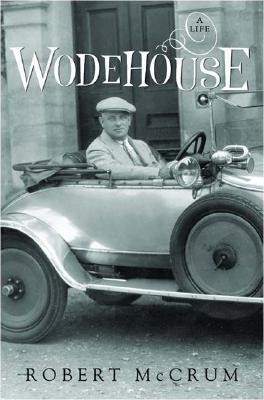

I recently wrote and recorded a song with my band The Paranoid Style called “Exit Interview With P.G. Wodehouse,” where I imagine talking to him later in his very long life about what he made of this episode decades on. The dilemma seemed clear enough to me: Wodehouse himself was not an evil man, but, in a moment of weakness, he had abetted the worst kind of evil imaginable. And what’s the difference? But I wanted to fact-check myself—and to see if my read on the situation was accurate—so I reached out to Wodehouse biographer Robert McCrum, author of the definitive 2004 overview Wodehouse: A Life. What follows is my conversation with him about what actually took place in 1940 and 1941, how Wodehouse briefly became a mouthpiece for Joseph Goebbels, and what we are to make of that now.

Included at the end of this interview is the worldwide premiere of “Exit Interview With P.G. Wodehouse,” now available as a Bandcamp-exclusive single.

Elizabeth Nelson: First, if it’s okay, let’s establish a timeline. In the winter of 1940, Wodehouse and his wife Ethel were cheerfully living on Le Toquet on the coast of France. The German army is marshaling its forces on the border, and yet, somewhat confusingly to me, many don’t imagine that those forces pose an imminent threat. Can you provide some context as to why in the world the Wodehouses are not panicked about the possibility of being caught in a German invasion?

Robert McCrum: Sure. Well, I think there are two main reasons. One has to do with Wodehouse and one has to do with history. Let’s start with Wodehouse: he was finishing a novel and he didn’t want to be bothered. His villa in Le Touquet is a charming house on the edge of a golf course on the coast. It’s very lovely. And he was a creature of routine. He would get up, write all morning, have his lunch, go for a walk, do some more work, listen to the radio, go to bed. So he’s finishing his novel, and it’s going quite well, and he doesn’t want to budge because he’s in a rhythm. And his wife, Ethel, she’s his facilitator. She runs the show; she does all the cooking and shopping. So the world situation is not very pressing on either of them.

Then there’s history: World War I occurred only twenty-five years before. Memories of that conflict are very recent. In World War I, the Germans never got close to Paris; they only got to the edge of France. And this was also during the period of World War II called the Phoney War, when there was not much actual fighting taking place. So even though the war was going on, it didn’t pose a threat to civilians. Plus, the Wodehouses are on the edge of the coast. They’re miles away from any likely hostilities. They’re just living in the bubble, really. And I think they thought the war would be fought somewhere else—that it would be fought in the middle of Europe and would never touch them. That was also, by the way, the advice they got from the BBC’s foreign office. They were saying the Germans will never invade.

Then, at the beginning of May 1940, the German army swept through France at an incredible speed. The French army, which had been dominant and expected to fight, instead collapsed and fled before the invading forces. They fled in such a headlong way that they were overtaken by the invading Germans. So that’s the situation. Suddenly, the Wodehouses have got Germans on their doorstep, and they’re in a panic. And it’s the one time in P.G.’s entire life when something of any consequence really happens to him.

EN: There is an incredibly funny and harrowing detail you provide in your book wherein Wodehouse is eventually detained and interned by the Germans. He’s given a short period of time to gather his personal effects, at which juncture he grabs his volumes of Tennyson and Shakespeare and several pipes but neglects to bring his passport which is . . . not good under the circumstances. Does this small anecdote tell us anything important about the man?

RM: He lives in the world of his imagination. He has no practical knowledge. He relies on his wife to do all the day-to-day stuff. It’s almost as though if he can get himself dressed and get to his desk, he’s happy. In many ways, he’s like a child; that’s him. Very impractical.

EN: So, during the time that Wodehouse lived as an expat, English attitudes toward the war are changing dramatically. Chamberlain has been replaced by Churchill and the country has assumed a war footing. Wodehouse, for his part, doesn’t quite seem to be tracking with this. He has a habit of talking constantly about how much he personally likes Germans. Is it fair to say that he was caught off guard by the escalation in hostilities?

RM: I think so, yeah. I mean, the only Germans he had ever come across had been when he was working in Hollywood prior to the war. There were a lot of Germans in California in the movies.

So his experience of Germans was German expats in Hollywood who were different animals altogether. They were not bellicose; they were very liberal, and they were very international. They were probably anti-Nazi. And I think it’s fair to say that until the war broke out, a lot of Europeans were not aware of the dreadful nature of the Nazi regime. Here in England, we became aware of the horror of Nazism through the bombings and the threatened invasion. Britain was involved in a life-and-death struggle against the Nazis, but Wodehouse was absolutely oblivious.

EN: And that’s just because he was away from the country?

RM: Yeah. France was at war but France had not been invaded. So, life carried on to a remarkable degree. People could correspond by post throughout the second world war and enjoyed reliable mail delivery in it. And a lot of stuff was going on in everyday life. And the horrors of the Nazi regime—the anti-Semitism, the concentration camps—none of that was known.

EN: Wodehouse is moved to three different detention centers in relatively short order. He’s also often subjected to significant deprivations. For a man in his late fifties accustomed to creature comforts, he seems to endure this treatment remarkably well. Was there something endemic to Wodehouse that made him resilient in this way?

RM: There’s a very simple explanation. He’d been to an English private school, Dulwich College, which is very, very spartan. It’s like being in prison. I mean, truly. Everything is prohibited or compulsory. Food is dreadful, it’s cold, there’s not enough heating or lighting. It’s a very basic existence.

So, when Wodehouse goes into these internment camps—as I say in one of the chapters of my book— he’s got his friends. For him, camp is really great fun; he loved camp. He loved the company. Now, please don’t misunderstand this. He was probably someone we would now describe as asexual. He loved the company of other men. He loved being a boy; he was like a head boy amongst all these internists. Also, he was really quite famous. He was renowned. He was quite beloved, so people paid him great respect. And he was very stoic. Kept a stiff upper lip.

EN: Wodehouse seemed, despite the seriousness of the situation, not to fully grasp the propagandistic implications of his stature as a world-famous and beloved figure. Is it fair to say he proceeded with a certain naivete once the New York Times and other publications began reporting on his internment?

RM: He was a very modest man. And one of his very attractive qualities came to the fore during his detainment: although he was so famous, he never flashed his character around the place.

Again, he lived in his own imagination, and that world was more real to him than the real world. And he didn’t understand the Nazis. I mean, the moral horror of Nazism is something which has taken a while for the world to come to terms with. At the point when the war broke out, they were just another bunch of Europeans. They’re just the European aggressors. They were not morally indefensible; they were not the Holocaust perpetrators. They weren’t war criminals.

World War I was such an old-fashioned war. World War I is two sets of imperial opponents battling it out in a horrible place. And in World War II, and it’s not just the war—it’s the conduct of the war. It’s the conduct of the oppression. The Nazis are capable of the unspeakable. That’s where Churchill is great. Churchill really gets it. And I think Wodehouse didn’t get it. So, if I came to you in the camp and said, “Elizabeth, would you do a broadcast on Nazi radio?” you would respond, “I’m really sorry, this is not for me.” Because you instinctively know this is the wrong thing to do. Wodehouse never got that. To him, appearing on the radio was like getting back in touch with the fans. We shouldn’t skip over his transfer from France to the internment camps. It’s very interesting.

EN: Can you talk about that a little bit?

RM: Sure. The journey across Europe was horrifying. I think some of the internees were shipped in cattle trucks. They didn’t travel in a car; they had no food. Some of them thought they were going to be killed at the end of their journey. Wodehouse never says that because he wouldn’t have thought that. Again, it comes back to his tremendous powers of stoical resilience. But the peril was truly profound. He was in his late fifties. He was getting on—it must have been very awful. I have been to the first camp where he was interned. It’s called Tost. It’s like a giant high school. It’s a very bleak place, but it’s also a big building—very imposing. Seeing it in person really helped put everything into context for me.

EN: It certainly seems like a great deal for a privileged man of fifty-nine to endure. How did he stave off despair?

RM: Again, because he had been in Dulwich, a private boarding school. He was in a dormitory with other men. He was familiar with that kind of life; he quite liked it. He liked routine, and they gave him a routine. They gave him a special room to work. It was spartan, but I think he was fine.

Now, if you want to go to a darker side, look at a map and note where Tost is. It’s about thirty miles from the site of Auschwitz. And there’s a thing I never put into the book, because it seemed too speculative, but there’s a road which runs past this building where Wodehouse was interned. And it’s inconceivable to me that they wouldn’t have seen troops, possibly even refugees—victims of the Holocaust—being driven past Tost to Auschwitz. So I think he must have known about it. Or, to put it another way, it would have been known about by his guards. There would have been personnel on the camp who were part of the camp system because Poland was basically a huge camp. There were the extermination camps. They were one level. Then there were camps for ordinary soldiers, camps for officers, and camps for internees who were non-combatants. And there were many opportunities for the staff and the prisoners at the various levels to interact with one another.

So I suspect Wodehouse knew. I don’t speculate about that in my book because he never refers to the extermination of Jews in his letters or diaries. So maybe he didn’t know—but a lot of people did know. At a minimum, I think he must have turned a blind eye.

EN: Oh my God. That’s rough.

RM: And it’s tricky, It’s certainly part of the reason why, after researching and writing about him, I liked him less. Because he’s a great artist, a great comic writer, a great freestylist. He’s got many great things attached to him, but he didn’t do well in his most important moment. He made a grave moral mistake.

EN: In 1941, the Germans moved Wodehouse to a hotel with the express purpose of doing these broadcasts.

RM: And it’s not just any hotel. It’s the Adlon Hotel, a five-star hotel in the middle of Berlin. It’s like the Ritz—very swanky—and it’s only a couple of miles from the Reich Chancellery. It was used by the Nazi high command, which was regularly seen in the bar. So, the more you get into it, the worse it gets. He was preening away in the toniest corridors of the Nazi regime.

EN: And the broadcasts they had him record were supposed to be just these sort of these lightly humorous dispatches?

RM: They’re pretty harmless. They’re not very funny. They’re sort of dull, actually. But the offense is the fact that he did them at all.

EN: What do you think the Nazis expected to get out of these broadcasts?

RM: Well, it’s a little mysterious why they thought this was a good idea. They were clearly desperate to keep America out of the war at any cost, and there was an ongoing propaganda campaign to this effect. Goebbels perhaps believed that Americans would hear Wodehouse carrying on affably, then conclude that Germans aren’t so bad and that the camps were essentially harmless. It absolutely did not work at all, but this seemed to be the basic thought process.

EN: How did Wodehouse rationalize what he was doing? How could he fail to anticipate the ugliness of the backlash? This is the part that nags me: a self-evidently brilliant man behaving with such lack of compass or common sense.

RM: I think he relished the opportunity to connect to his audience, whom he felt estranged from. Some famous writers are unreachable; they won’t give interviews or engage meaningfully with peers or fans. Wodehouse was the total opposite. If anyone wrote him a letter, he would write them back. He was addicted to that kind of attention. He would have undoubtedly been addicted to Twitter.

As to why he did not foresee the consequences—a full and total disgrace for England—I think it’s just that the world of imagined was more real to him than anything else. He loved and was addicted to writing. He was a master of English prose. With that prose, he created an alternative universe, one in which his characters never experienced any serious problems. In Wodehouse’s universe, there’s no death. There’s also no sex. The worst thing that can happen is somebody punctures your hot water bottle or something.

EN: So when the violent backlash to his apostasy occurred, Wodehouse was genuinely taken aback?

RM: He was mystified. And I think he never got over it. I’ve spent time talking to people who knew him, including his grandson Edward, who runs the Wodehouse estate on Long Island. Edward would go for walks with his grandfather around the estate late in Wodehouse’s life, and he would say, “Do you understand what was so wrong about what happened?” Wodehouse just didn’t get it. It’s bizarre, but I think he thought he’d been trying to be patriotic. It’s actually a tragedy, and I think he was haunted by it. His work certainly never recovered. If you read the later books, there’s no lightness. The books of the 1930s and 1920s, on the other hand, are just joyful.

EN: To sum up, his German adventure was disastrous on a truly Wagnerian scale. As his biographer, what’s your final take-away from this event? As Wodehouse’s readers, what should we take away from it?

RM: We’ve talked about his naiveté. But he wasn’t really naive. I think he was simply unequipped to make the right judgment. He was profoundly selfish. All he wanted to do was write his books and not be bothered. He didn’t want to engage with the problem. Imagine George Orwell put in a camp at that time and what you’d get from him. Or any great American writer of that era. You name one; they would have responded.

But the fact was that Wodehouse had no curiosity, no interest. Utterly selfish, utterly a creature of his own world. He was by every account—and this should be emphasized—a nice man. But, as history has a tendency to lay bare, being a nice man and being a good man are not necessarily the same thing.

Elizabeth Nelson is the singer-songwriter for the Washington D.C. based garage rock band the Paranoid Style, whose five wildly-praised releases on New Jersey’s Bar/None Records have been described as “glam rock for the end times.” She is also a regular contributor to the Ringer, New York Times Magazine, Oxford American, Pitchfork, and Lawyers, Guns & Money.

Cambridge born writer, editor and historian Robert McCrum is the author of 2004’s P.G. Wodehouse: A Life, a best-selling biography. He has published several novels and works of non-fiction, and served as editor-in-chief of the publisher Faber & Faber for close to twenty years. His most recent book, Shakespearean: On Life & Language in Times Of Disruption was published in 2020 and has been praised as “a beguiling mix of memoir, literary criticism and biography.”

More Interviews