Difficulty Is My Drug of Choice| An Interview with Dennis Cooper

Interviews

By Troy James Weaver

Dennis Cooper is probably best known as the author of the five novels that comprise the George Miles Cycle (Closer, Frisk, Try, Guide, and Period). But he’s also written and directed two films, Permanent Green Light and Like Cattle Towards Glow, and prolifically collaborated with many other writers and theater directors—most notably, Gisèle Vienne.

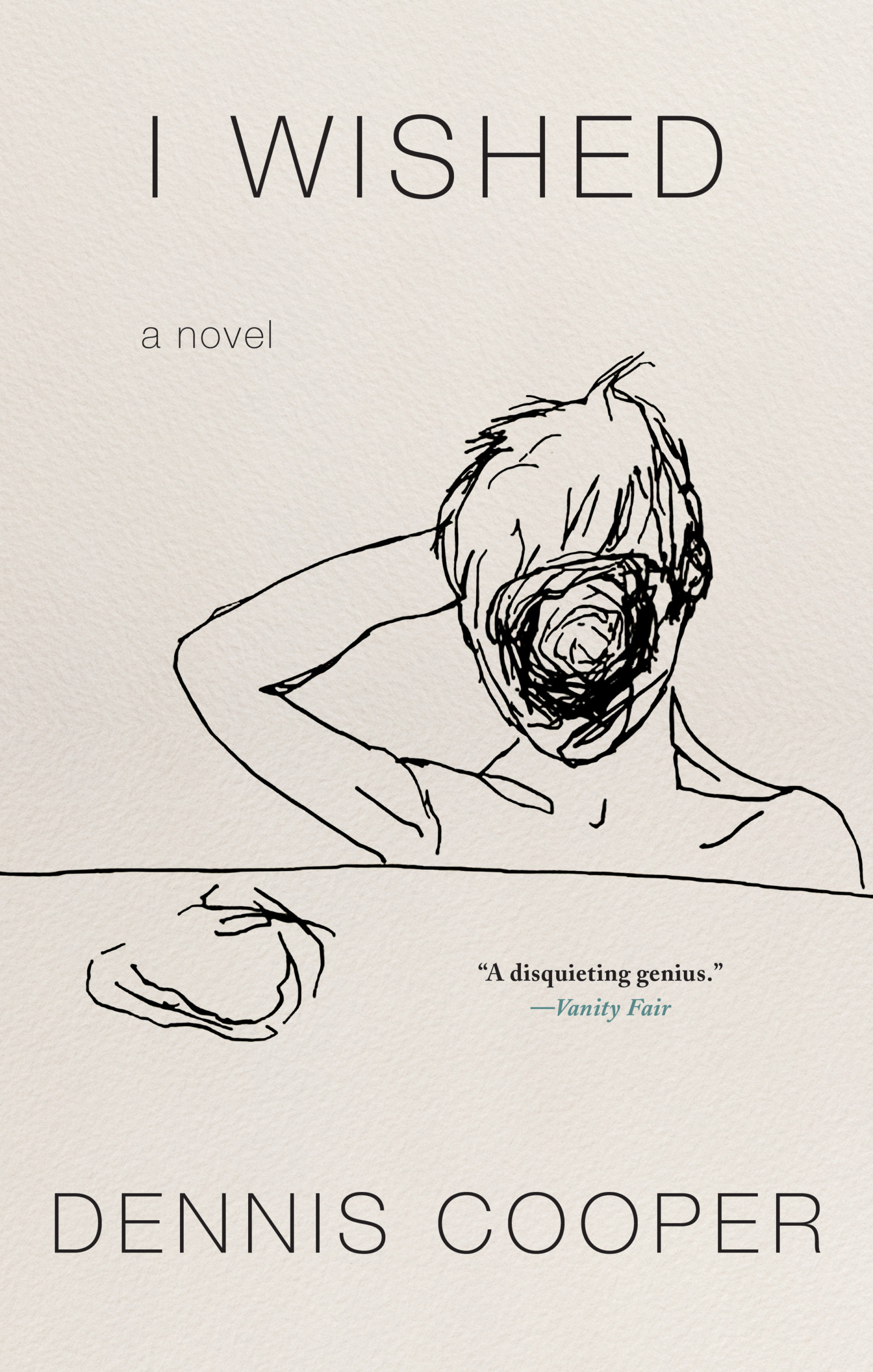

Cooper’s latest book, I Wished, stands alone in the same manner that his earlier novels My Loose Thread, The Sluts, God Jr., and The Marbled Swarm do. However, its subject, George Miles, is the very reason his first five books exist at all. However the reader chooses to categorize it within Cooper’s oeuvre, I Wished is a deep, troubling, yet ultimately beautiful meditation on loss, art, love, and motivation.

In I Wished, we are given a glimpse into how Dennis Cooper and George Miles met, then guided through a bizarre yet beautiful series of imagined events. George has a conversation with a crater about existence, Santa Claus gifts a gun—John Wayne Gacy even makes an appearance. Cooper uses these devices to explore his obsessions, comprehend why his friend committed suicide, and make a case for a bond that not even death can break. I Wished isn’t about George Miles so much as it’s about Dennis Cooper’s attempts to understand himself and his motivations for making the kind of art he makes. Ultimately, it’s a plea for his love for George to be acknowledged and, impossibly, reciprocated.

I recently had the great pleasure of talking to Dennis about I Wished via email.

TROY JAMES WEAVER: I’ve read most of your books. This one is so much different. More meditative, almost philosophical. It’s almost entirely interior. The narrator (Dennis) is orchestrating every movement, trying to understand an impalpable need. Does grief ever go away? If it doesn’t, does that mean our love is stronger? Weaker?

DENNIS COOPER: I can only speak for myself, obviously, but I don’t see grief as some monolithic thing. It can be unshakeable as in the case of George’s death, but a lot of the time it’s just very confusing. Sometimes it’s abstract and triggers thoughts about death in a general way. Sometimes it’s fleeting and mostly disturbing because it’s so brief and weak. The interesting thing about grief, for me, is that it never ends. Love ends, hatred ends, but I can think about a friend who died decades ago, who wasn’t even a close friend, and the fact that he’s dead still fucks me up. Is love stronger when the person you love is no longer there to interfere with it, or is love in that case just an act of exploitation and self-indulgence? I don’t know.

TJW: I feel like you explore that idea in I Wished, that uneasiness, but you undercut it at the end of the novel. Is this an idea you came to while writing this book, or have you had similar thoughts while working on other books?

DC: I think I’ve always had that idea in my mind when I’ve written. Maybe it’s because of the confrontational subject matter I decided to address in my work when I was young, but it’s always been important to me to think carefully about the power dynamic between that material and me, between that material and the prose I use to represent it, and between that prose and the reader. I always think about the issue of fairness: how to be fair as a writer. So my thinking about that idea is intricate and kind of built-in. Writing this novel about George made me think about it maybe more directly than I have before.

TJW: For me, reading I Wished was a sort of spiritual experience. Like witnessing an interrogation of self into the varying modes to which we are trying to explain the unexplainable, or rather, the unknowable, to get to some point of actualization. Your love for George Miles is always there, but it seems as though the book is more about a seeking of his acceptance, or approval, or love. I realize that the book is fiction, but I also know that it is, like all great art is, a landscape of your interiority. I’ve read in other interviews that you had an earlier draft you thought didn’t cut it. What was so different with the second draft, the draft that became I Wished?

DC: Thank you, Troy. Your characterization of the novel is great and heartening. Before I wrote I Wished, I wrote a first draft of basically a whole novel about my friendship with George. My approach was to do a factual, chronological recounting of our relationship from the night I met him until I found out he had killed himself. It was very, very wrenching to write, but, when I finally looked back over it, the novel just didn’t work at all. It exuded none of the intense feelings I’d had while writing it. It just seemed inert and private and tiresome. So I had to toss it, although the section of I Wished called “The Heart is a Lonely Hunter” was the very beginning of that novel, which I salvaged. When I started over, I took a completely different approach. I basically just riffed off of my emotions and ideas and didn’t worry how they would fit together and cohere. My friendship with George was pretty chaotic, at least on the surface, and I realized the novel needed to appear similarly kind of unmoored formally but deeply unified by the seemingly indestructible emotional attachment happening underneath, if that makes any sense.

TJW: There are these great scenes in the book, like George having a conversation with a crater, or the section with Santa Claus, or the part with John Wayne Gacy, that to me, are not only affecting, but really work narratively, despite how bizarre they at first seem. I was totally convinced George was speaking with a crater. But something more powerful happens when you realize that George is talking to himself, through the crater, because Dennis is making this happen. And Dennis makes it end, too, when he closes the laptop, squishing them beneath its weight. Do you find that you can only speak truthfully about George artistically?

DC: As I write in the novel, it’s not hard for me to talk about George truthfully in conversation or whatever. I sometimes feel really compelled to. The obvious problem is that no one I talk to about him knew him personally, so they’re only really thinking about what his effect was on me, and I’m never looking for sympathy for me when I talk about him. I just want to be his mouthpiece. I want people to help me figure him out. It’s true what I wrote in I Wished: that I tried to get my therapist to let me talk about George and give me her insights about him while divorcing me from the equation, which was absurd to ask. In art, I can take my time and use whatever talent and skills I have to “bring him to life,” even though the same problem remains. And he was so complicated by his disorders, that even I, who knew him very well, don’t think I ever understood him. So writing about him is setting myself a theoretically impossible task. But I’ve always tried to write novels that seem impossible to actually realize to the degree I want when I start them. I don’t know why, but I’ve always been compelled to challenge myself as much as possible when I write, for better or worse. That difficulty is my drug of choice, I guess.

TJW: This book was put out by Soho, a press I really love. What was it like working with them? How did the experience differ from other publishers? Would you ever consider publishing with a much smaller press? Do you think there is more freedom in doing so?

DC: It’s been nothing but fantastic working with Soho. It hasn’t been really so different from working with Grove Press or Harper Perennial, for instance. One great thing is that my editor is Mark Doten, a novelist I admire a lot, so working with a fellow novelist I respect has been a true bonus. Sure, publishing with a smaller press would be great, and I’m sure I will. I mean, probably 90 percent of the books I read are published by small presses. It’s the world I know and trust and feel comfortable in. More freedom, for sure. I should say seemingly so since I’m a small press reader more than a small press author so far. Really, given the current publishing world, I don’t really even see an advantage to publishing with a so-called major press anymore. I suppose writers might get larger advances there. I suppose major publishers have more of an “in” with the traditional book media like The New York Times and New York Review of Books, etc. But does that book reviewing hierarchy even matter anymore if you don’t write books aiming for spots on bestseller lists and a chummy welcome by the literary establishment? The kinds of writers I’m interested in only wind up fêted in that echelon on very rare occasions and by some weird fluke.

TJW: You’re a very big champion of younger writers and smaller presses. Have you always been a champion of the underdog, period, or is it more that you see more potential there than at bigger presses?

DC: I guess I’ve always been supportive of other artists, even when I was young myself. When I was a kid, maybe ten years old, I built a theater in the attic of my family home and encouraged my friends and kids in the neighborhood to write and act in plays in my theater. And I think I continued to like to encourage writers and people who wanted to be writers however I could, through the literary magazine and two small presses I edited, for instance, and now with my blog, which feels kind of like editing a magazine in a way. I’m a person who gets very enthusiastic about writing that excites me, and since my own work is known to some degree, I’m in a position where, if I enthuse about a book, people seem to trust my judgment in some way, and it seems to have an effect. I’ve always been most excited by daring and/or uniquely voiced writers, and I guess those qualities make them underdogs, but I think of them more like exploding bright lights or something. I definitely see vastly more potential in the smaller presses and the writers they publish. I read voraciously, and, like I said, with rare exceptions, I’m reading books from small presses almost entirely. It even feels weird to call them small presses since what they’re doing is so big.

TJW: Your blog must be a tremendously time-consuming endeavor. Can you tell me a little bit about how you view blogging as an art form?

DC: I don’t know if I think of blogging as an art form so much. Well, I think magazines and anthologies are art, so I guess I do. But blogging feels more like an act of curating or editing than like being an artist who works in the form of the blog per say. I guess I think that what I post about is art in most cases, and it’s about how to juggle and arrange that art in the blog’s very limited space and format or something.

TJW: Can you list ten of your favorite books of the last ten years, ten of your favorite classics, and ten of your favorite bands past and present, please?

DC: Oh, gosh, there have so many books I’ve loved in the past ten years that I don’t think I can reduce it to ten. I’d end up only thinking about the books that I was forced to leave out. How about if I list ten of my favorite publishers and presses of the last ten years, because that might be easier? If that’s okay. In no particular order: Semiotext(e), Dorothy, Amphetamine Sulphate, 11:11, Expat, Calamari Press, Inside the Castle, Wave Books, Ugly Duckling Presse, Civil Coping Mechanisms. See, even only picking ten presses is super hard. My favorite classic books might be (again, in no order) Maurice Blanchot’s Death Sentence, Agota Kristof’s The Book of Lies, Robert Pinget’s Fable, Ivy Compton-Burnett’s The Present and the Past, Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Recollections of the Golden Triangle, Raymond Roussel’s Locus Solus, John Ashbery’s Three Poems, Joy Williams’s The Quick and the Dead, Max Frisch’s Man in the Holocene, the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom. And my favorite bands, wow, okay, off the top of my head: Guided by Voices, Wire, Cheap Trick, Spirit, Pavement, Autechre, ABBA, Sparks, Captain Beefheart & The Magic Band, The Shangri-Las.

TJW: What are you working on now?

DC: Zac Farley and I are preparing to shoot our third feature film, Room Temperature, hopefully in February in Southern California. Also Zac, the writer/curator Sabrina Tarasoff, the musician Puce Mary, and I are finishing a virtual walk-through video game-like haunted house project that will premiere this Halloween at The Pinault Foundation in Paris. I’m writing the text for a new theater piece by the French director/choreographer Gisele Vienne that I think will premiere next fall. And Zac and I co-wrote a strange little novella called The Has-Been that we’re almost finished with. So those things and the ongoing blog are the main things I’m working on right now.

Troy James Weaver lives in Wichita, Kansas, with his wife and dogs. His work has appeared in New York Tyrant Magazine, The Nervous Breakdown, Lit Hub, The Fanzine, Hobart, and many others. His books are Witchita Stories, Visions, Marigold, Temporal, and Selected Stories.

More Interviews