Down the Hatch: Barstool Chats with Hosho McCreesh

Interviews

By Ross Nervig

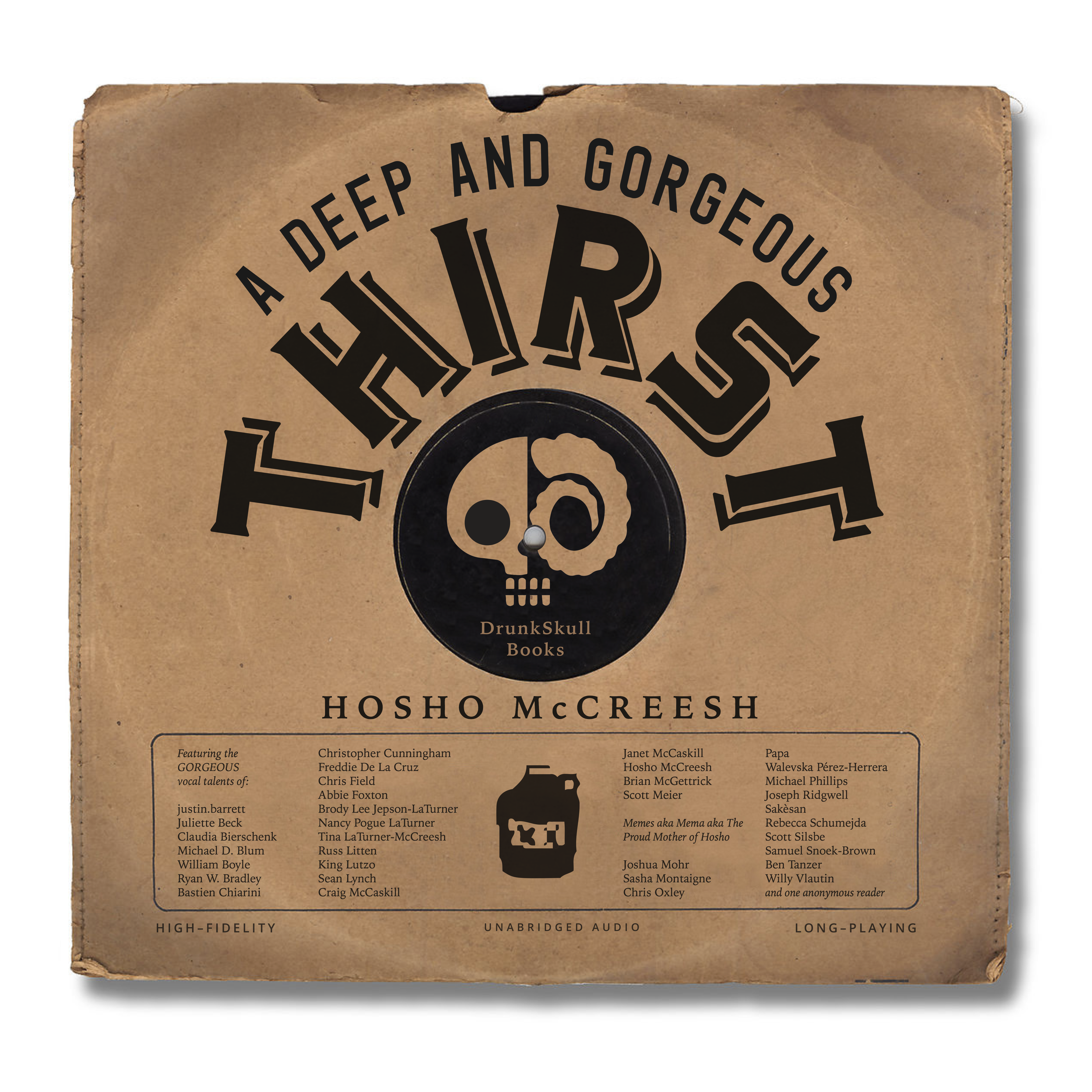

“For me, drinking has almost always been about joy,” states Hosho McCreesh in the introduction to his latest collection of poems, A Deep & Gorgeous Thirst. “And learning something about my own limits, and about the limits and capacities—good and bad—of the people around me.” McCreesh’s book is a transmission from the wrong side of 3:00 a.m. when nary a good decision can be found. In these pages, the reader is led through the author’s “T&T years,” “The Tom Collins phase,” and countless other rounds of cocktails, beers, and wine. But even as this book is about drinking, it is really about the people with whom we choose to drink, to commiserate, to laugh, and to cry. The thirst of the title could also be our thirst for camaraderie and community—the longstanding tradition of gathering at the local watering hole to share jokes and tall tales. Each poem is a little vignette rendered with the warmth of friendship and indeed much joy. In an era when sobriety and healthy living are often trending topics, it’s refreshing to read a series of poems that toasts the joyful act of getting fucked up. Hosho McCreesh writes and paints in what he refers to as “the gypsum and caliche badlands of the American Southwest.” He is the author of six books of poetry, a novel, two short story collections, and a work of nonfiction. I spoke with Hosho to mark the release of the audiobook of A Deep & Gorgeous Thirst.

ROSS NERVIG: Who is Hosho McCreesh?

HOSHO MCCREESH: Well, hell, right out of the gate you’ve stumped me! Who can say? Your guess is as good as mine. Maybe someday I’ll know. Until then, I guess we just have to “accept the mystery.”

RN: The main voice of the collection speaks in the second person. Is the you you? Or is it a drunken persona or an avatar for the reader?

HM: I’d say it’s both. While the work is largely autobiography-by-drunk-poem, it was also an attempt to capture some of the intimacy and immediacy of those crazy, unexpected barstool chats folks will sometimes have with some character sitting one seat away. It’s one of the reasons the poems don’t have titles either. I wanted the read to feel like one of those wild, churning, even dangerous nights, for the reader to get dragged along for the shenanigans and the unapologetic joy of a good ol’ drunken dust-up.

RN: You are participating in the ancient tradition of drunken poetry. Li Po was practicing drunken poetry in the early eighth century. The Greeks were definitely practicing it in an even earlier epoch. How did you come to write in this vein? How do you honor the genre and how do you subvert it?

HM: I mean, I love Li Po, and Kobayashi Issa—there’s such humor, and deeply human stuff packed in between the drinking and suffering. Obviously Bukowski is a huge influence on me as well. But I feel people are quick to dismiss his work because it seems so deceptively simple, and because it was so hacked up by his editor after his death. I’d say that trying to write something in this vein is to honor the genre . . . with the caveat that, if you do try, you damn well better have a fresh angle. As to how I subverted the genre . . . I guess it’s that I didn’t actually write a book about drinking . . . it just seems like I did.

RN: What poets or books of poetry acted as guides during the writing of A Deep & Gorgeous Thirst? How and why? In other words, if you could pick three poets, living, dead or immortal, to get drunk with, who would you pick and why?

HM: Writing is, in many ways, an accumulation of influences and techniques, and the more you write, the harder it becomes to actually track it all back. I certainly think, in terms of ambition and scope and the free rein of subject matter, Leaves of Grass played a part. Small press stalwarts like Annie Menebroker, Doug Draime, and Albert Huffstickler certainly played a part in the writing. They’re all just 100% themselves—no artifice to their work. It’s fearless in that way.

RN: At 322 pages, A Deep & Gorgeous Thirst is the length of three or four books of poetry. When did you know you had a collection on your hands? What effect do you hope a book of this length has on the reader? How did you change during the process?

HM: I think all the changing happened before I started the manuscript . . . and the changes were seismic. I was as happy as I can ever remember being, having reconnected with my now wife, and seeing my future in a way I truly never had. And I knew as soon as I landed on the idea and finished the first poem that I had a new, huge project on my hands. The first drafts were fast and loose; then I pushed myself, editorially, as hard as I could—determined to not waste a single word, and challenging myself with the structure of the book as well.

As for the effect: simple . . . I want the reader to be drunk and happy and hung up and sad and to laugh out loud and feel that hard-won redemption of riding out the toughest years to eventually find yourself truly happy in ways you never knew possible. Is that too much to ask?

RN: How did the unabridged audiobook come into being? How is the experience different for the listener than it is for the reader?

HM: It’s definitely more immediate, I think—more approachable. There’s something almost primal about being read to—something that taps into the oral tradition of human development. It’s a completely different feel than reading, different than the voice in our head. As for how it came about, an old college buddy happened to be in town during a reading I did. He’s an actor, directs theater, does voice-over work . . . and he said the book would translate well, and thought I should make an audio version. I just couldn’t see how it could be done. The poems don’t have titles and I figured it would all just run together, and I had no idea how to solve that problem. “Easy,” he said, “just use a different reader for every poem.” That was it. I started planning and gathering recordings soon after—reaching out to friends and family the world over, to other writers I knew. And six or seven years later, here we are.

RN: You live in Albuquerque, New Mexico. How has the area affected you as a writer? What influence has it had on your practice? Conversely, this book spans the entire globe—finding you drinking and writing in Japan, France, and Mexico among other locales. Where is your favorite place to drink, and where is your favorite place to write?

HM: While it’s a place with deep and rich, interwoven cultural influences, New Mexico is also a poor state. And anyone who has known economic desperation will instantly recognize a very specific mindset: which is not having time for bullshit. To me, that also happens to be a pretty terrific approach to writing. Say what you mean, mean what you say, and you damn well better be interesting enough while doing it; otherwise, clam up!

My favorite place to drink: anywhere, so long as I am with my people, everyone cracking wise, trying to make each other laugh.

As for my favorite place to write: at home, no shoes, in my bed, under the fan, with some music on. Naked, if I’m being completely honest. I need as few distractions as possible . . . and I have a tactile thing about clothes, materials—have [had] since I was a kid—I just don’t prefer them. Turns out they frown on such things at Starbucks.

RN: What is next for you in terms of writing?

HM: I’m not actually sure. I tend to let the dust settle between projects, and then go where the juice is, working on things as they demand, until one project grabs me by the throat and it’s all I can do to get it finished. I have a short story collection, another audio idea, some uncollected poetry, other novel ideas . . . I’m close on an art book. I guess I just piecemeal things until one finally refuses to be ignored, and I disappear into it.

RN: I’m not gonna lie. I felt a little hungover after finishing this collection. Best hangover cure?

HM: That depends on where you are, and if you’ve just finished drinking or if it’s the morning after. If you’re in New Mexico, and it’s the morning after a bender, it’s gotta be huevos rancheros, or a sturdy breakfast burrito. If it’s the night of, my go-to for years was western-style hashbrowns at The Frontier. If you’re on a tear in Europe somewhere, I’d say a kebab is pretty solid boozy fare. For the morning after, maybe an Irish fry or croque madame. If you’re in Japan and it’s cold out, I’d say some train-station ramen, or maybe some tonkatsu. If it’s just a dull-drunk headache you’re trying to nurse, a bloody mary or a red beer probably does the trick.

Ross Nervig is a writer living in Nova Scotia. From 2012 to 2017, he served as a founding member of Revolver—a literary arts collective based in St. Paul, Minnesota. His work has appeared in Kenyon Review, Bluestem Journal, Bayou Magazine, Southwest Review, and HuffPost. He is currently an MFA candidate in fiction at the University of New Orleans. In 2018 he received the University of New Orleans Creative Writing Workshop’s Ernest and Shirley Svenson Award for Fiction.

More Interviews