Fresh Whole Milk

Web Exclusives

By Claudia Smith

I’m in her closet. The door is closed, and I am not allowed out. Am I locked in? Or am I simply that good at obeying? Or is it that I am too afraid to come out before I’m told?

There is a sliver of light at the bottom of the door. How long am I inside the dark? I can smell her in there: Ivory soap, room freshener, detergent. I miss her in that animal way of children who crave their mothers. I’m trying to be as still and quiet as I can so he will let me out. That is the trick. The trick is to rest my ear against the cold floor, to make my brain hum, to feel myself go flat. Like it won’t matter when he comes. Like I don’t care if he comes or not. I can hear the hum of our house; of our dog, Albert, out back, panting; of my father’s movements; of the refrigerator switching into high gear. And when I stop crying, if I fall asleep or make up a story inside my head and squeeze my eyes tight against the semi-dark, he will come. He will come when I no longer need him to come.

I feel my mother. Well, not her. But pieces of her. Her shift dresses, in avocado greens and denims of the seventies, the belted shapes that hold her for me in a way nothing else really can. I know when she comes back home will be home again.

It could have been hours; it could have been minutes. But oh the relief, when the door opens wide and my father is there. I love him completely. He has rescued me from the kind of dark where you don’t know what scuttles. He says, “I don’t love you when you are like that.” But he says it so gently. His arms around me as he hugs me against his chest. And I tell him that I am sorry. And then after the reconciliation comes the beautiful excess: Franken Berry cereal, as much as I want. I eat bowls and bowls, gulping the pinked milk. Oh, deliciousness. Mom, he says, would never allow you to eat this. Isn’t this fun?

There are two families, and I don’t know which one to believe in; they are both real, and one family cancels out the other. They cannot exist together and yet they must.

There is the frail evening light in a kitchen we lived in long ago, a kitchen in various states of disrepair because it has been hit by hurricanes and punched around a bit. There are no blinds on the windows, and the sky is that weird bruised kind of Houston sky that arrives with the storm season. We are all at that table, eating the nutritious-but-budgeted dinner my mother has prepared. There is salad and there are pork chops and tumblers of sun tea. Or lentil soup. Or sunshine squash from the garden.

There is the kitchen before that, candles on the table, casting the three of us in shadow against the wall. My mother and I in matching homemade peasant dresses. And then there is that same table, my father gone, my brother’s listless body as my mother props him in the old high chair. “What’s wrong?” I ask her. Later, we will discover he is in a coma, but my mother has washed him, bathed him in the sink, dressed him as always. “He is just asleep,” she’ll tell me. “He needs to sleep to get better.” At the table there is thick, watery milk made with powder. I know the powdered milk means she is worried, and that fresh whole milk means she isn’t as afraid.

And there is another family in another room, at the same table. The father chews with his mouth opened, and the daughter looks at her plate, at the emptied parking lot outside the window and the garbage piled up against a rusted metal fence. “What’s wrong?” the father asks. “Look at me. Look at me now.” And later: “Look what you made him do.” And still later: “How many of these did you take?” And even later: “We did everything we could do.”

My mother and I, sitting across the table from one another. I’m twelve; she is thirty-four. Her rough salt-and-pepper hair is pulled back into braids. She is still a young woman, but she possesses the fierce plainness of frontier women in the books I like to read. Her body, as her husband, my father, has said to us several times, is so different from mine. At twelve I am already curvy. She is willowy, regal, even when haggard; I’m all tits and ass.

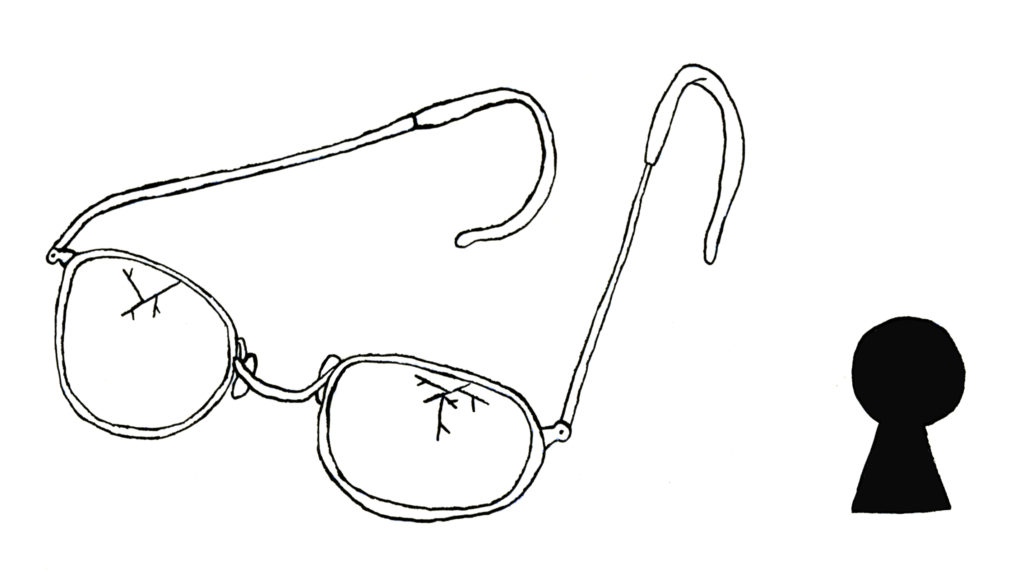

At twelve I will want to save her. He isn’t home and she complains. Who else can she talk to? She tells me what he has done to her. She tells me secrets, too. She talks about a man she loved before she loved him; she tells me how my father left her crying after her first miscarriage; she talks about her wedding night, when they had to figure out sex together. But I can’t criticize him too much, or she will snap back: “Don’t ever speak about your father that way.” She will slap me hard across the face so my glasses fly. And when she does, we both pull back from the sting. Her eyes glittering, fierce, eyes you don’t question.

She never warns me about the slaps. They seem to take her by surprise as much as they do me. When she is angered, her voice lowers. I don’t hold it against her, as I do him. I won’t cry. I won’t sass. I will sip my coffee and she will sip hers: mine black, hers with cream. That’s her one indulgence, she likes to say. Cream instead of milk.

My brother Charlie is in my room, playing dolls with me. Holly Hobbies. Carrie Hobby is the most beautiful one but not my favorite. Her eyes are too blue, her hair too flaxen for anything other than angelic thoughts. She is the fragile one, always needing to be carried as the Hobbies flee the child catchers. Amy, sturdy with her two brown braids and dull tan bonnet, is my favorite. She pulls her sweet, good sister in a makeshift sleigh. It is snowing, we pretend. It is a blizzard, and they must find the magical blueberries in the snow to cure Carrie’s cursed illness. The blueberries in the snow I’ve lifted from a book of fairy tales I read at our grandparents’ house; in that tale a beautiful maiden is forced to wear a paper dress and go in search of blueberries in bleak winter, which of course she finds, thanks to the aid of fairy folk.

Sometimes, I lie in my pink twin bed as Charlie watches me. I allow myself to slip out of the bed. “Help me, Charlie,” I say in a flat voice. “I’m falling.”

“Claudia, are you okay? Why are you doing that?”

“I can’t stop myself,” I say, and he comes to my rescue, but I crash anyway. “Stop me, Charlie. Help, help—I can’t stop myself!” I am laughing hysterically.

“Claudia?” He stares at me. He’s supposed to be the one with problems. “Don’t do that. What if you really hurt yourself?”

I find a pincushion in the bathroom cabinet and stick needles through the fleshy tips of my fingers. He doesn’t understand that this does not hurt terribly. I like impressing him. “Look what I can do, Charlie.” He is impressed, but he doesn’t like it.

When we painted the trim in my room Country Peach, we did not paint the inside of the closet. It is still a true 70s brown, and I go in there at night when it’s already dark to feel even more of the darkness. I can hear my parents clearly; the closet wall is their wall. But I feel I’m in a bubble, sort of like being underwater. I can hear them, but I doubt they hear me. I take a needle and push it beneath my nail. I practice silence. I don’t want to hurt myself really; I don’t push it that far. I bite my bottom lip. The test is: how silent can I be? Every time I try, I am able to push the needle a little deeper.

When I threaten to run away, Charlie will insist he is coming with me. So I stay, of course.

But he doesn’t know this. None of them do. Some nights, I go ahead, lift the window and climb on out. What would happen if I just ran? I walk to the fence and think about going over it, into the deep field of rats and thickets.

Claudia Smith’s essays and stories have appeared in several journals and anthologies, most recently in Another Chicago Magazine, The Texas Review, Gay Magazine, and Norton’s New Micro: Exceptionally Short Fiction, New Sudden Fiction: Short Short Stories From America And Beyond, and others. She has two flash fiction collections, The Sky Is a Well and Other Shorts (Rose Metal Press), Put Your Head in My Lap (Future Tense Books), and a short story collection, Quarry Light (Magic Helicopter Press). She is a lecturer at The University of Houston-Downtown and is currently at work on a memoir.

Illustration: Josh Burwell is an artist and illustrator from Mississippi currently living and working in Los Angeles, California. You can find more of his work at jburwell.com or on Instagram @jburwell.

More Web Exclusives