Genius Insurgent? | The Life and Art of Dave Hickey

Reviews

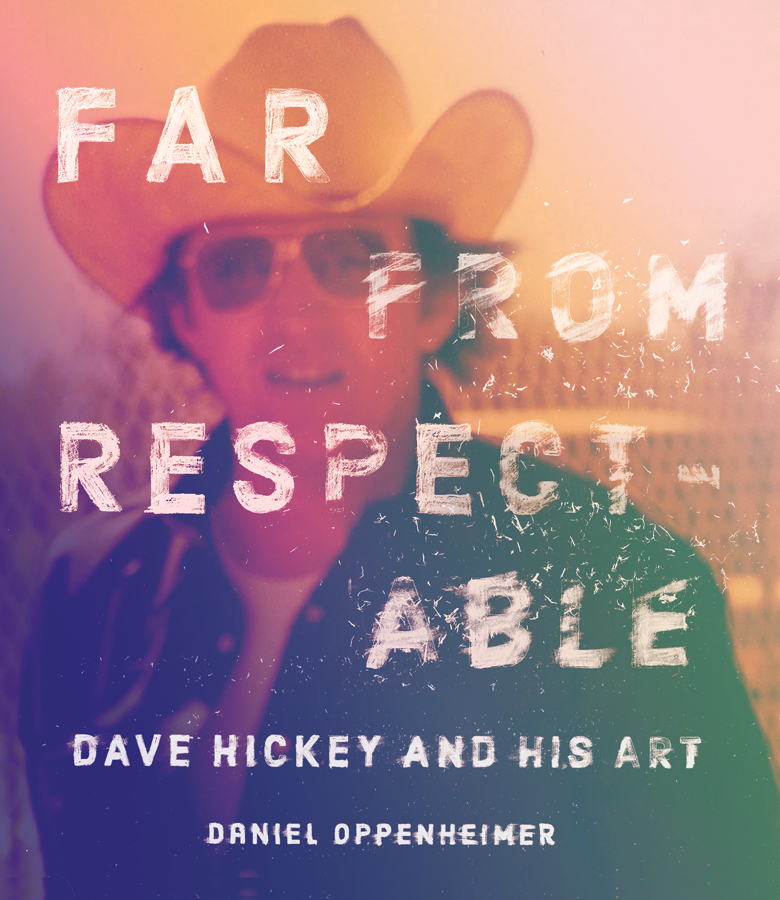

By Odie Lindsey

Daniel Oppenheimer’s Far From Respectable: Dave Hickey and His Art is definitive. You should read it, and you will enjoy it at a level that may depend upon your familiarity with the deified and demonized essayist, who you will either: a) know, and thus already be in dialog with Oppenheimer’s impressive work; or b) not know or know much, in which case you will be compelled to go and read Dave Hickey and maybe watch him on YouTube. The book delivers insightful, detailed overviews of Hickey’s biography—from boyhood in post-war Texas, to NYC gallerist, to premiere art critic and cultural provocateur—and his career highlights: written, lauded, vilified. Notable here are the included snatches of Hickey’s writing—from his books The Invisible Dragon and the canonical Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy—as well as an unflinching essay and interview Oppenheimer completed last year, with Hickey staring at life while half-enfeebled in New Mexico. Still bladed, still relevant, still contentious, a beast: Dave Hickey.

Oppenheimer is up front about his relationship to his subject. He is a fan and seeming acolyte, and, to an extent, well . . . if not an apologist for some of Hickey’s transgressions, he is, at the least, a bit of a sidestepper.

This position brings a divisive point to bear on how to review the goddamned book. Thing is, Hickey’s cultural presence has been co-constructed by his outsider, art populist persona, e.g., his disdain for MFA programs (which he’d abolish), by routine quips about “ugly” art or pretty women, or his takedown of just about any cultural organization not named MacArthur (which awarded him its so-called “Genius” grant in 2001), etc. As such, a question: if Hickey’s imperative and myth are symbiotic with his detractors, what level of responsibility is there to document that dissention?

Oppenheimer does devote attention to the “blob of curators, academics, review boards, arts organizations, governmental agencies, museum boards, and funding institutions . . . who impact art.” This is necessary, given that these academic “-ists,” likewise .gov and .org-ers often exist in a state of co-revulsion with Hickey, and that they do shackle, shame, dilute, and/or co-opt creative process and aesthetic value on the reg. Yet the inclusion here is in service to the subject himself: Hickey is misunderstood; Hickey is not what his detractors claim; Hickey is needed now more than ever, etc.

Which may be true. Which is true, if the work is standalone, if the work is narrative, versus history. The question, then: which is it? If narrative, refer to paragraph one.

Note: I have and am often enthralled by Dave Hickey’s genius, his craft. His attitude. For me, his work embodies a fucked-up love affair: worshipping the whole is to overlook massive faults. The relationship can break you in two. (To wit: the first draft of this review was written in first person plural.)

Considering art and culture, “Hickey was skeptical of interpretations that leaned too heavily on straightforwardly political or economic explanations for why people were or weren’t likely to invest in a given work.” Instead, Far from Respectable circles a recurrent term, “ethical cosmopolitan paganism,” a practice Hickey once believed to be ascendant, and by which you, me, we, they, should worship at the altar of whatever “art” gives us meaning—be that Ed Ruscha or Gustave Flaubert (or whatever a “Caballero kickflip backside lipslide with a fakie 360 flip” is, as was attempted, repeatedly, at last month’s Olympic skateboarding final). This concept speaks not to the clinical dissection of art by its sociopolitical imprint but to the pleasure we derive from communicating about our object(s). This giddy communion, individual or tribal, stands in as the true currency of beauty, and thus the most important determination of artistic worth—no matter if some scholar, gallery, or “Aryan muscle boy” institutionalist says otherwise. The “cherry on top,” according to Oppenheimer, is that as result, we are enacting democracy.

What’s more—and this is important—Oppenheimer makes clear that Hickey wasn’t claiming some universal, “apolitical, ahistorical” and immutable notion of beauty, something handed down and canonized by authority. Rather, again:

Beauty was that set of properties in visual appearance that elicited pleasure and attention in people, and it was related in complex ways to what people hated and loved, dreamed and feared, were or weren’t capable of thinking in a given historical moment. The line-up of winners and losers was changing all the time, as various players, ideologies, politics, economics, tastes, and fashions drove some into and out of the canon and others towards oblivion.

Only, as is claimed early in the book, ethical cosmopolitan paganism “is in retreat, not just from the ethno-nationalist”—my read here being evangelicals, Trumpists, supremacists, and related louts—“but also from puritanical intellectuals and activists who would regulate culture in the name of justice, equity, and identity.”

Beating back this squeeze, alongside Hickey’s brash, charismatic brilliance, is what launched him into the essayist stratosphere some thirty years ago and makes for a ripe attention now. Far From Respectable contends that Hickey’s critical liftoff occurred amidst the culture wars of the ‘90s, upon his assertion that the notion of beauty “had been vanquished from the sphere of discursive concern,” when “meaning, discourse, language, ideology, justice” all but consumed the dialog around art.

Maybe. And yet, how convenient.

Sidebar: applause to Oppenheimer and the University of Texas Press for avoiding the disaster that is in-text citation. Adjacent to this, while our biographer does once use the word “ensorcell” (Oppenheimer, 27), a term I refuse to look up on principle, well, the rest of Far from Respectable is high bar get-able. His work is smart and lovely, and in service to his groundbreaking subject, while keeping readers in mind. The biographer understands art, theory, culture, craft, and Hickey, and, importantly, doesn’t punish us when we don’t. (Which is often.)

The book adds to established, formative narratives: Hickey’s surfing and car culturing; his father’s musicianship and eventual suicide; the art world tastemaking in Austin and New York. What’s more, it brings new attention to the writer’s crash-burn stint in 1970s Nashville. We gain a true sense of Hickey’s immersion at the time—creatively, critically, culturally . . . destructively.

Having parted with the apex gallery scene in SoHo, Hickey joined Nashville’s yet-to-be-trademarked “outlaw” country music culture, linking up with fellow displaced Texans like Waylon Jennings and Billy Joe Shaver, while dating a kindred genius, singer-songwriter Marshall Chapman. Hickey covered the nascent, backlash movement for Rolling Stone, the Village Voice and others, and recommitted to his own songwriting. He landed a music publishing deal, smeared himself across the honky-tonk and guitar-pull scene, and stood side-stage at industry events. He was also pharmaceutical, a self-described “fucking disaster.” The resultant personal collapse coincided with the commercialization of the renegade movement itself. Hickey bore witness to an era where every dicked body in Music City had incentive to mimic Ole Waylon, forcing the outsider culture in and feeding its own brand of blob. “I still don’t really understand that period of my life,” Hickey says. This, too, is crucial, in that the experience informed his pivotal work to come, namely The Invisible Dragon (1993), and Air Guitar (1997).

Far from Respectable makes the case that Hickey’s lyricism and intellect eclipse any bro-ness of his biography. Yet that bro-ness and ego, and perhaps the inability to dismantle his intellect or belletrist prose, make him the ideal stabbing dummy. He is excessive. It’s delicious. His populism can be maddening, and insulting. As Oppenheimer notes:

Hickey and his allies could seem like, and in some cases were, structural bedfellows of the political conservatives who were attacking contemporary art for being too black, too queer, and too secular. And Hickey, as a persona and public figure, wasn’t able or willing to extricate himself from this perception. Too often he chose to . . . play the asshole they assumed and very much wanted him to be (the better to dismiss his critiques).

And who isn’t drawn to the genius insurgent, or the pleasures of heart and eye, hand and gut? Yet is there is anything more political, more institutionalized, than the sidelining of bodies? If not, let’s discuss. If so, see paragraph one.

Odie Lindsey is the author the novel Some Go Home and the story collection We Come to Our Senses, both from W.W. Norton. He has received an NEA fellowship for combat veterans, the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Prize in Fiction, and the Dobie Paisano Fellowship. His website is oalindsey.com.

More Reviews