Gleebombs & Humhearts: A Conversation with Abraham Smith

Interviews

By Elijah Burrell

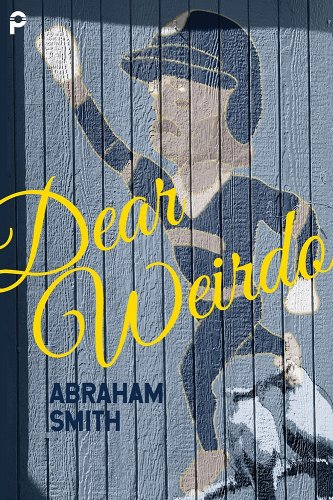

The first time I heard it, I found it hard to believe. No one had knocked on my door in a long time. I’d spent all morning alone, sipping coffee, watching the quiet earth spin below me. Most days, my full-time job was wondering how I got here to begin with. None of that mattered now. Poet Abraham Smith, hot-blooded in the cold of space, had come to pay me a visit. I looked past him, saw his rental car parked in the lunar dust, and we awkwardly bumped our fists together as he came inside. No need to worry, I said. It’s good air up here. He saw the copy of Dear Weirdo, his newest book which, a few weeks before, I’d found floating in the back yard. I apologized for how far he’d come, and he was good enough to say it was no big deal. He’d made a mixtape for the journey. He said he just pushed a few buttons and bam.

I remember how they always told me there’s no water up this far. I guess they’ve never seen my place. Over the next few hours, Abe and I stood beside the reservoir and cast our lines into the water. The lures floated just above the surface. Every so often a celestial bullhead or crappie came into sight and stared at the cold reflections from the baits’ blades. I said, You’ve got bullhead up in Wisconsin, right?

Sitting on the porch, the milky way just over the horizon, we talked and then talked some more. When we got to poetry, I felt like I was falling back into something. It’s true that we had to pull ourselves down into our seats every so often—because of relativity—but perhaps other forces were working at us. Here’s what I managed to take down of our conversation.

ELIJAH BURRELL: Abe, I once described your style as a waterfall’s continuous gush. I think it’s because I couldn’t—in the moment—come up with a better metaphor. Anyone who’s read your work over the years will expect both the challenge and satisfaction found in Dear Weirdo’s eighty-one pages of (mostly) unpunctuated, overflowing lines of poetry. Your lines in this new book are relentlessly imaginative and contain moments of intermittent beauty—or ugliness—that startle the reader and provide what I treasure above most things in poetry: surprise.

One thing I’ve always admired about your work is how you manage to lull the reader into floating along until whirlpool, rainbow trout, large rock, mama fox on the bank. What the reader might believe are random amblings, in my experience with your work, are setups for subtle variations and knockout images.

the butterfly besets the fleein fieldmouse

bird upon bank glass angst

breakneck ball palmed

of ransomed beauty

let this poem pal w/ gentlefoot god

reader deer don’t the rain get in

yeer bubblegum machine mind times

more need spleen yellow

gobsmack black never

meant to be seen static daisyface neon

still finch hey slow this hair part down

prone knife crayoned with margarine

death renders everyone open object for eye pry

and here comes the poem upon

slippery glitz where you stand

comes from givin those pompons

the royal treatment

with a late springtime attitude

bird bank to you

The alliterative voice hypnotizes the mind, but what hits me hardest is the image of a “prone knife crayoned with margarine” and how “gentlefoot god” and “gobsmack black” pair up and retrovert into something really interesting.

Can you talk a little about the process in which you first construct what I’ll call “the beat and chord progression” of a long section of poetry?

ABRAHAM SMITH: first, thanks so much for the generous grace words. (kind)means the whirled world. these were started as particulate matter–little separate horseshoes and oxbows of song and poem. is that a dime or diamond or ball diamond in the lint trap? i think back around 2019. soon in the manner of snakewintersleep xmas light tangles, i could tell that nothing started and everything started and nothing ended and everything ended. every pond is lazy rain. soon we all give up and just plug in the snakeball of xmas lights but briefly lest the curious cat singe on a glow binge. as i gambol thru life, i see hitching-posts not hitches in the getalong. little hidden plug-ins at the airport if you are willing to sit on the zombie-walked hair&dust cement-integument-carpet. not fissures but fusers and fascia.

EB: Ok, but once you hold the snakeball of lights, what kind of work does it take to bend the lines and phrases—the glow-binge-cat-singed moment—the sparks of language that indelibly join the whole thing together?

AS: life for me is not separate from poetry. i am all the time abandoning the song for the email. and the song stuff sticks to email with apologies to everyone i’ve ever emailed. right now i am writing this and loving the cranky mockingbird up the japanese maple and the squirrel impossible upon the raingreased white fence. tuscaloosa blues gruel to sip at while i find these sentences’ sizes. for me poeming is living so it’s play. now and then consternation for sure but only a little. life has a rill–a lip full of heartjuice feel. and i live to love to play the lines along and down. so revision for me is choosing my toes as stethoscopes to listen in to the heartbeats of frogs. feeling for the sweet sometimes jagged simultaneity of pulses. how they stack and slide.

EB: About seven years ago I wrote a poem about how death can and does shock us when we’re unprepared. Mike Ayers’s 2020 book One Last Song asks thirty-two musicians to answer the question “What’s the last song you’d want to hear just before you die?” What’s your last song?

AS: easy! spring peepers overlain by silver lacquer of sandhill crane.

EB: That makes a lot of sense. The forever rolling sound of those peepers busted up now and again by that almost-prehistoric, dignified crane call. It’s also a metaphor for Dear Weirdo. Margo Price took part in One Last Song too. I notice she’s written some nice things about this latest book of yours. I’ve always appreciated how dedicated she is to following the long line of Woody (especially in her earlier tunes), Hank, Townes, Willie, and Tom Petty. You’ve spent a lot of time thinking about Hank Williams—you wrote the electric Hank, after all. Can you talk about your connection and kinship to folks like Margo Price?

AS: margo i had the jumping joy to share a stage with in nashville for a business show she’d signed on to sing for, at frye boots. from her deserved perch, the swag is everyday, but i gotta tell ya, that was some pretty neat rare glee to be paid for poem-sermoning with new cowboy boots! and the dots-connect came from our shared Third Man: many mergansers of gratitude to ben and chet and everyone there: as ya know, they put out her first two records and my farming poembook Destruction of Man. we’d been mutual fans for a bit and a beet of days and years there so it was darn exciting to finally meet up in person. i later heard my kangaroo footstomping sent the stageful of instruments to swaying like herons on a waterbed. gladiola to this day i didn’t capsize all their beaut and regal stringed things. later margo’s manager led us through a labyrinth of hallways to her green room where we had a dandy hang. she’s from rural northern illinois and her mom was around back there as well so we all kinda talked that midwest kind gravel road talk. had some deep chats and herniating laughs. as fancier green rooms tend to be, the foods and tipples were epic. i yet recall the vat of plain yogurt that none of us could figure the meaning of. sorta looked like an aerial view of a snowy soycorn field. songsters and booksters share equal space, same soft lob lobo lights on my heart. gus cannon and washington phillips and blind willie johnson and geeshie wiley and courtney marie andrews and marisa anderson and gwenifer raymond and michael hurley and bill morrissey and norman blake and mance lipscomb and lilly hiatt and bukka white and on and on. i grew up on woody guthrie and leadbelly then branched willowly from there. and i take charlie parr’s songs like vitamins 7 times a day 8 days a week.

EB: I don’t think we see enough baseball in poetry. When I came across . . .

how goes yr mathmind wind?? and

is tomorrow actually another day cat?? or

is countin sexy?? ueck don’t seem

to think so but this

this we do know

rob deer is out and trottin

back to the outfield like he did

33 too many squats in his sleep

I just had to smile. I haven’t thought about Rob Deer in decades. Mostly I remember him from his 1987 Topps baseball card. This was the year Topps did that woodgrain around the borders of each card. I didn’t know much about the Brewers, then, being a kid from Missouri, but I remember staring at that Rob Deer card longer than the others in my pile. This is no action shot. He’s leaned up against a practice net, with that splendid mustache and wavy hair. I’m not trying to describe him like Homer would Hector, but here we are. I can remember, at ten, thinking this baseball player seems somehow gentler. Might have been the name. Maybe I’ll call this memory Deer Weirdo. He hit only .238 that year, but he put twenty-eight over the fence. Tell me about baseball, Abe. I’d like to hear how and why Deer, Bob Uecker, and the Brew Crew came to mind as you wrote this book.

AS: i had those same woodcut topps! my heartpace and place is forever back home in northwestern wisconsin: rusk county. most of the green welding i do poetrywise comes from there. thank god i have long arms for reaching. and yes i do listen to the brewers on the radio on many a sunny afternoon in utah. in utah, the sun is relentless. in wisco, uecker is deathless. he’s been the stained cardtable i’ve been leaning on at the kid table on thanksgiving forever and day. and i grew up playing. pitching some. once i forgot to wear socks. and threw a wild pitch. then stared at my bare left ankle. very glad to have socklessness to blame. those spiked shoes were very uncomfortable. like wearing plastic icetrays. deer came along around when you knew it’d never be 1982 again. there at the queasy fulcrum between innocence and experience. and deer coincided with the understanding that the hell in my family was only growing hotter. i was afraid most of the time. and we’d moved deeper into the country. so besides the far drumbeats of loving grouse and the nimble nimbus chickadee ways and maybe del shannon and megadeath on the tape from that mail order music service we all believed we were really crafty scamming, the one thing i knew i had was the radio upstairs on a metal chair that helped it come in gooder. and i remember, on one very boring and lonely fall afternoon, deer blasting a homerun and uecker going bananas just like he still does. get up get up get ouuuuuut of here and gonnnne for deeeer! and not feeling alone just then. and jumping and jumping and bleating hurrahyesss, the dried raspberry jam crusty on my fingers buggering to the floor. see, i knew he was going to hit that homerun. i could feel it seconds before it happened. deer laundered my head while he eased around the bases. homerun hitters are hapless strikeout kings. ain’t that life. sweet pure hopeless hopeful potential happening again.

EB: In those lines from before, rich with baseball, you use “mathmind.” I dig how you invent compound words as shorthand in your work: “gleebomb,” “daisyface,” and “humheart.” I see it as one of your stylistic signatures. Where does this impulse come from?

AS: i’ve long had a grudge against curtains. i am the guy who yanks the blinds up to the top and maybe never quite gets ’em let down even ever again. never invite me by unless you love a good full window! i was reading joy williams the other day. what’s that other older word for blinds? jalousies? she used that. when my dear old pal bill saw the end of his life coming he said it’s curtains for me. and on the lighter side, zippo not bic, my bud bronson says when they are on tour and sicktired, they’ll steer the band van through neighborhoods until they find a street of houses where the blinds aren’t mangled up like glue spaghetti water snakes in loons. windows and the world are one. life and poetry are one. i am pretty sure i wrote letters like that back in 1991, welding words. and pretty sure i wrote years of emails like that, hugging words. and buckets full of phone texts like that, feral herds. so it’s most natural that words demo derby like so in my poems. with gratitude winks to kennings and gerard manley h!

EB: I think Hopkins wrote for himself and for God—then he quietly sent his poems to his friend Robert Bridges. Do you ever have a particular audience in mind as you’re writing book-length poems? Who do you write for?

AS: well i suppose i write to know and care for myself a little more and to shake the nests of my days: every day i trot and jostle thru the streets sky and hills and trees. writing is a little like spreading a sheet under the trees of the mind, giving into things and giving things a little dramatic dance rattle. let the sound and shine love gravity, out and down. catch it all up into a knapsack circled soon by flies and bees. and you betcha: the titanic sound poet steve timm. we meet up in madison wisconsin now and again. sit up late reading our latests back and ford. if he’s not sighing and giggling like a pressure cooker fulla geraniums then something ain’t right with my rites and rays.

EB: What’s the first poem that ever really got to you?

AS: maybe frost’s The Road Not Taken because i memorized it when i was a kid for class. my sister jess always hated milk thus drank it by pinching her nose and gasp-gulping at the same time. this was the pinchy way i memorized that poem. today i still like to share with students some of frost’s phrases: especially that negative capability vibed icecube on a hot stove dealio. and definitely bob dylan: songs like Hurricane and Motorpsycho Nightmare. Hurricane was that waterfall. and Motorpsycho Nightmare was delicious for its rhymes, tho maybe he laughs at us in that snotty little ducking ride. we had and we read the reader’s digest so i knew he was saying that country folks were limited by what made us feel wider when the dad in the tune goes and lobs the reader’s digest at the picaresque lover fella. and the kindest guy ever, our auto mechanics teacher up at the high school, went to school with zimmerman in hibbing and said he was distant even when close, in short, a short snot. but then dylan’s laughing maybe while he’s singing. and you have the sense that he’s unmaking the song just as he’s making it. that his living body is intervening in the song. and i very much loved that. and live that.

EB: Towering Bobs—Frost and Dylan. I don’t think “Motorpsycho Nitemare” gets the attention it deserves. “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” from Bringing It All Back Home is the one people talk about. Those two songs share an identical rhythm and giggly cynicism. I get what you’re saying. I see it in your work.

Speaking of bodily intervention in song-making, I know a lot of folks ask you about Frank Stanford—or suggest the voices in your books sound like faraway echoes to those in Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You. Irving Broughton once asked Stanford, “What is strange to you? When did you realize this strangeness?” Someone had to ask. I’m interested in your answer to this as well. Also, is there such a thing as ugly?

AS: probably i am closer text buddies with dh lawrence. i was rereading his collected the other day. there in the so-called last poems he has one where he’s talking about not pigging out on apples and he has one where he writes of the flower he leads with on his march thru this april called life: the flower as forked torch. mmmy! but, yeah, frank s came to me via craig arnold. we were writing letters back in 2002. i sent him a long and screeching poem wherein my gramps made love to a white pine tree to get our sawdust barroom floor fam kicking. arnold wrote back, read frank stanford but don’t do what he did. then i went to jackie’s lounge to play pool badly with david floyd and john pursley iii. and the next day around 945am after bad sleep with a beluga of a headache i dutifully checked out the selected poems of william stafford from the university library. and thought, craig? what? were? you? thinking? anyhow back to the letter and back to the library to check out The Light the Dead See. and bingo: i saw right off that frank and me were writing similarly twisty wild dog puffs and huffs and barfs and barks. i’d lie to say it wasn’t a great beam of beauty light to find him. i believe my beloved poetry brother steve timm gave me the gift of the battlefield in 2003. suddenly folks in workshops saying i like the music but have no idea what you are saying didn’t hurt me. i had the frank turtle shell helmet on when bill knott told me i’d never publish a poem. i had the frank turtle shell helmet all the time then. and then i saw that i already knew frank from lucinda williams’ pineola song. and then i wrote cd wright at lost roads thinking if frank and me share better than a bittern river of blood then maybe she’ll dig my melty jar jellybean poetries. and then in 2003 she wrote me a small email and i walked on air for years. just knowing she cared enough to say, you have something going here, hold your nose, send to the contests, endure, really did potpourri my pigeon and velvet cake my ramen. and so, to answer your question, irregularity is beauty and today thursday yes feels very weird and dear. and it’s true: the squirrel must have teacher-seat-tacks in the toes.

EB: That story about mistaking Stafford for Stanford is priceless. Did you know the original first line of that famous Stafford poem goes, “Traveling through the dark I saw Rob Deer”?

Now that I think about it, you do belong in Lawrence’s bloodline. Maybe it’s his rhythmic patterns and phrasings—the intensity and sensuality. The “daddy” in that Lucinda Williams song is, of course, Miller Williams, who taught Stanford in the poetry workshops at Arkansas. It’s cool that reading him helped you through your own workshops. Sweet Old World for sure.

AS: heehaw that’s right. ol deer robbin the road of its golden bifurcations. one of my favorite things to do to this day is to walk deer trails thru woods. better still rabbit trails. better still owl butterknife sky trails. better still coyote song snake snail moon sails. lucinda’s been a blessing upon this world. grapeful she pulled blaze foley into people even if folks thought Drunken Angel was about townes. and love that she brought bo ramsey in for a song on Car Wheels. and hate that bo ramsey’s old runnin buddy and brother-in-law—mr greg brown sir—is retired. every so often i’ll just go ahead and lay down like a dog in the honeylight in greg’s miraculous run of poemful-song records from Down in There through Over and Under.

EB: We’ve come to that common moment in these conversations where I ask you who you’re reading lately. Let me also ask what contemporary music you hear these days that reaches you.

AS: back through some james baldwin and willa cather’s One of Ours and adalbert stifter’s Motley Stones and joy williams and back through some william blake and bohumil hrabal and and nella larsen and back through some clayton eshleman. it’s a mighty pile and i am forgetting most of the key wobbles and keg cogs. i only feel okay when a talus scree of books is a threat to kill by avalanche my shucked off wool socks. is umm kulthum contemporary enough? how about willie dunn? i was just chairdancing and headbangin to those two seconds ago. my friendship with charlie parr is a most treasured thing: he’s shined some highbeams on strudels of musics utterly new to me, given my natural inclination to dig a deep hole in raw and crackly folkblues and crawl in and craw inner. so now see i wag like ferns under pines during thunderstorms to the universal liberation orchestra and brotzman graves parker and gonora sounds and young/jewell/walker and irreversible entanglements and ava mendoza and daniel bachman and ryley walker and kikagaku moyo and gunn-truscinski duo and lubomyr melnyk and the list goes so very onnn!

EB: We were talking about Dylan earlier. Someone asked in ’66 why he stopped writing protest songs. He said, “I’ve stopped composing and singing anything that has either a reason to be written or a motive to be sung.” Is it important to you to make specific political commentary in your books? Your work already gives us the mouth of a graveyard and a highway of diamonds, but do you want to regard the larger scale around you? There are particular moments in Dear Weirdo where I believe you capture the current, crass, “burnbarrel fire” of the American zeitgeist.

…keepin us out of

foreign wars and savin babies cryin

like babies lockt in school closets

the gun beyond closer

goin blam faster how can it faster

than yr heart goin so fast the beats melt into one

sustained udddd he’s handin out

upside down big mack leviticuss

to them clemson tackle boys main thing is

give ’em what they are used to

Here you’re name-checking Leviticus (which, when spelled “leviticuss,” is itself a commentary), school shootings, reproductive rights, and the imbecilic scene of Clemson’s football team served fast food in the East Room. I guess all of us are going to get what we’ve gotten used to?

AS: well it’s back to the waterfall baptism back to the weather news that the lightning don’t just strike the lonesome oak: instead it spiders out and zaps the oak and the praying-mantis shaped loose-tea thing scuffled to the back of the forkspoonknife drawer and the paperclip on the benchwarmer’s tiny-font stats and the band on the whooping crane’s corn-stalk-like leg and goes and makes a goo of the tinsel hauled by a rat to the attic. so i don’t feel i am reaching toward the political so much as just convincing myself i don’t need a cart at the grocery–yes i am the guy carrying 13 things at once. am i wrong that dh lawrence writes like he’s conducting an orchestra with sneezes? and let’s ride a tinsel goo jalopy back to cd wright back to forrest gander. in Be With he starts out with intimacy and the political twined. and now i am thinking of vic chesnutt. how his songs sometimes feel like they are built from slippery bread: it’s all that egg paint, probably. poetry for me is this: dizzy luv. and yes: i-you-we can, carry it all.

![]()

Abe left me on the moon alone. It’s different here than I imagined it would be, and our conversation reminded me of home. As we talked, and I looked into the vast nothing of far-light and dark, I saw how it all bends and blends together. As I scanned, I caught intermittent sparkles that startled me with their beauty. From Hydra (had I ever even noticed Alpha Hydrae out there?), to the all-bright Regulus, to Cancer, to darkness. Then—of course—dear Mother Earth, who day by day, unfoldest blessings on our way. It’s a lot like this poetry I’ve been reading up here, I thought. Floating then whirlpool, rainbow trout, large rock, mama fox on the bank: stars, constellations, STAR. When we’d finished talking about all the usual things in uncommon ways, I asked him the question that had burnt slowly in my mind since he first arrived: Abe, tell me what’s on that mixtape of yours.

Elijah Burrell was raised in Missouri and has lived there for most of his life. Aldrich Press published his second poetry collection, TROUBLER, in 2018. His first collection, The Skin of the River (Aldrich Press), was published in 2014. Burrell received the 2010 Jane Kenyon Scholarship at Bennington College, where he earned his MFA in Writing and Literature at Bennington’s Writing Seminars. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in publications such as AGNI, North American Review, The Hopkins Review, The Rumpus, Sugar House Review, Measure, and many others.

More Interviews