Life Circulates Around Us & Writing Is What We Do with It

Interviews

By Ryan Ridge

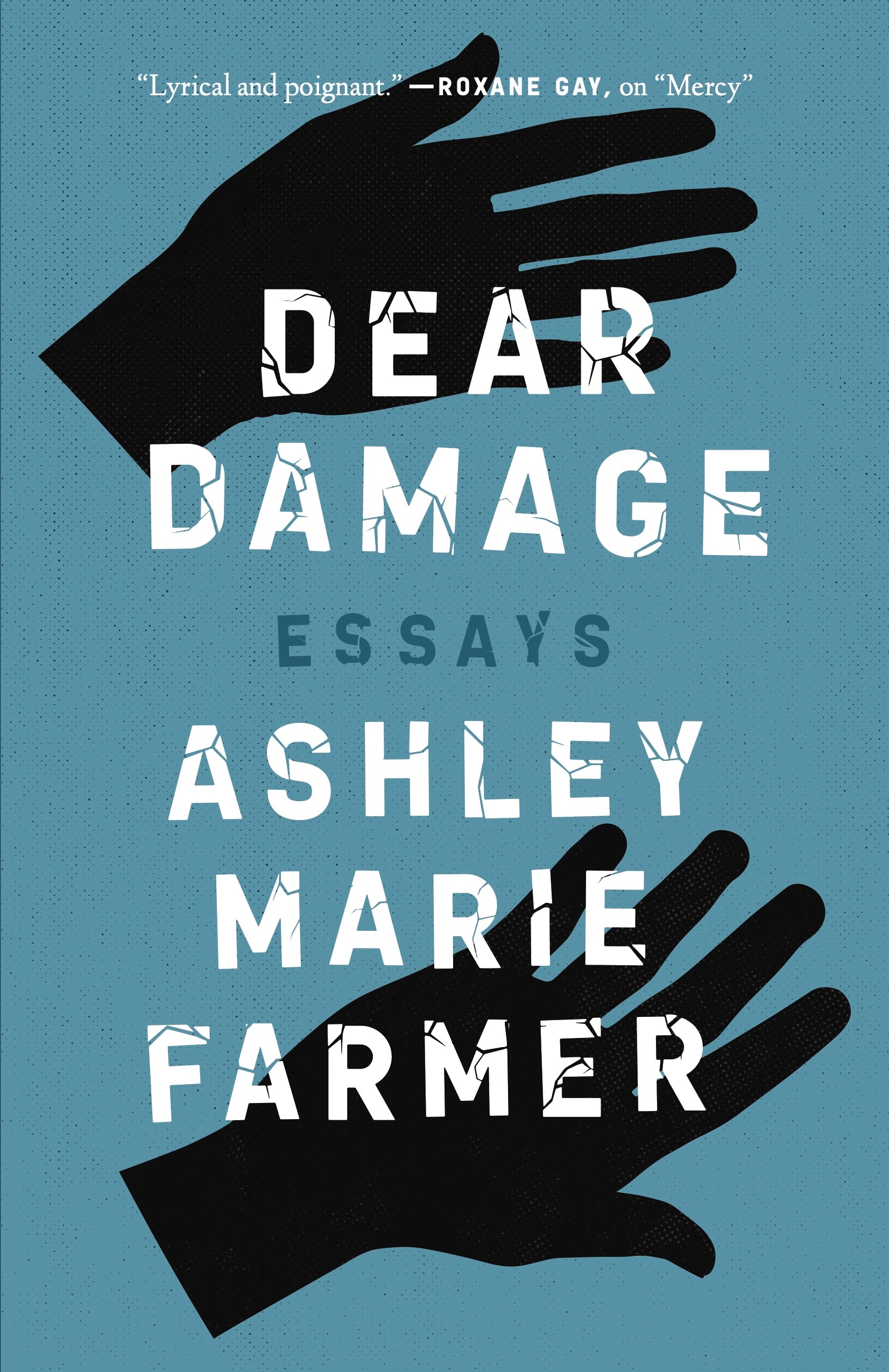

Ashley Marie Farmer is a poet, memoirist, and fiction writer living in Salt Lake City, Utah. Her latest book, Dear Damage (Sarabande Books), is a dazzling collection of essays that explores family, gun violence, art, love, and the American Dream. The book opens with an essay about her grandfather shooting her grandmother at a Carson City, Nevada hospital in 2014, an action that was deemed a mercy killing. Through legal documents, audio transcripts, internet comments, and other materials, Farmer reflects on this public incident and weaves together a story about family that crosses three generations. In a starred review, Publisher’s Weekly says “this astounding collection . . . introduces Farmer as a writer to watch.” The preeminent public intellectual of our time, Roxane Gay, calls the title essay “lyrical and poignant.” Acclaimed memoirist Justin St. Germain hails the book as “a marvel, a reckoning, possibly a miracle.” Celebrated novelist Michelle Latiolais says of Farmer’s collection: “Rarely are readers gifted with the work of a mind equally incisive as it is elegant.” Indeed, Dear Damage is an innovative exploration of grief in our collective age of anxiety and further proof that poets write the best memoirs.

Ashley Marie Farmer is also my wife. As partners for fifteen years and writers who have lived together across cities and decades, we spend a lot of our time discussing various creative endeavors, reading each other’s drafts, and helping each other make rough work smoother. Indeed, we spend many hours talking about words, but we’ve never had the chance to interview one another. This was a fun first for us. Thanks to Southwest Review, the greatest lit mag on the planet, for making it happen!

RYAN RIDGE: This book is a departure for you, genre-wise. Other than having folks read it (ha!), what’s different about working in creative nonfiction?

ASHLEY MARIE FARMER: Sticking to the facts was an interesting change—nonfiction creates a set of constraints, which is compelling and tricky. In working with family history and documents, my work was laid out in front of me: the story I needed to tell was already there, and it became more a matter of how. With fiction and poetry, there’s a mysterious process in which I stumble around, search for surprises, light up corners of different possibilities to see what will work for a particular piece. But in this nonfiction book, surprise came in the form of small decisions I made along the way, like which strangers’ internet comments to include or how much I shared about my mom’s life before she had kids. There was more planning in this book, more outlining. But, in some ways, working with the truth is freeing: the events have occurred, the material is there, and it’s a matter of shaping it and giving it energy to bring the reader along with you. It’s more like sculpting something from clay rather than inventing it in a laboratory.

ASHLEY MARIE FARMER: Sticking to the facts was an interesting change—nonfiction creates a set of constraints, which is compelling and tricky. In working with family history and documents, my work was laid out in front of me: the story I needed to tell was already there, and it became more a matter of how. With fiction and poetry, there’s a mysterious process in which I stumble around, search for surprises, light up corners of different possibilities to see what will work for a particular piece. But in this nonfiction book, surprise came in the form of small decisions I made along the way, like which strangers’ internet comments to include or how much I shared about my mom’s life before she had kids. There was more planning in this book, more outlining. But, in some ways, working with the truth is freeing: the events have occurred, the material is there, and it’s a matter of shaping it and giving it energy to bring the reader along with you. It’s more like sculpting something from clay rather than inventing it in a laboratory.

RR: What was the biggest challenge?

AMF: There’s a responsibility that comes with writing about family. I wanted to tell the complicated truth, be honest about my own experience, and also do right by everyone in the book (i.e., people I love). Those things aren’t necessarily at odds, but it’s a tightrope. I also wanted to be sure I had the details correct—that I was really precise. And that just takes time. I did a lot of double-checking, asking my mom if dates and sequences of events were correct. (Asking you, too; I’m so glad your memory is more meticulous than mine!). I just couldn’t be freewheeling in the same way I have been in other books. The challenge here was to go over it again and again until I’d done my best to be accurate.

And to be honest? Another challenge is that I’ve cared more about what people think of this book. Specifically, my family, you.

Do you think you’d ever work in creative nonfiction?

RR: Doubtful. Unless it wasn’t about me. My life isn’t the stuff of literature, and writing about it doesn’t interest me much. Karl Ove Knausgård I am not. That dude is a cautionary tale. Maybe he should’ve taken after you and cared more about what people thought. He really went for it in his books with ruthless attention to detail, and now he’s friendless and his family won’t speak to him and even his dog despises him. But he’s rich as hell and internationally known. I guess that’s the trade-off when you do a deal with the devil and write a tell-all. When writing Dear Damage, did you ever have to beat back the tell-all impulse, or do you not possess that particular writerly tendency?

AMF: No, that was never a temptation. I’m not someone who lays a lot of their life out there. I mean, I overthink the most innocuous tweets or pieces of flash fiction that bear any resemblance to my real life. So, it felt like a stretch in this book, putting personal details on the page for readers I might never meet. Strangely, writing about the painful subject matter was easier because it was already out in the world as public knowledge, while writing about the sweeter things made me feel more naked. At any rate, I was very selective, especially when it came to considering which stories were mine to tell versus someone else’s. And when I was in doubt, I scrubbed those things out altogether.

RR: I knew when you had a project (and it’s in the book), but when did you know you had a project on your hands?

AMF: Well, I actually remember you telling me I’d write about the incident between my grandparents when things were still heavy and fresh, very early on. That’s how writers think (well, the two of us at least!): life circulates around us, and writing is what we do with it. Plus, I’d planned to write a California/family book, even before things happened with my grandparents, so I had a little bit of that work finished—the essay about us packing the red truck and leaving Long Beach. But writing the essay “Mercy” and publishing it in Gay Magazine was a game changer for me. That was the first piece I’d written directly about the shooting. To have it selected for publication made me think, okay, this is worth finishing.

When did you know?

RR: It was the day after the shooting. I read a story about your grandfather’s actions in The Guardian, and I knew you had a book on your hands. Given that the events had become an international news item, I felt that it’d take at least a book to process all of the pain. But, at the same time, being a writer makes me think like a scoundrel. If I remember correctly, I said to you the day of the tragedy: “Well, you’ve got a book here,” which is the last thing a person wants to hear when they’re in the depths of despair.

AMF: That’s right—you said exactly that. Honestly, it wasn’t the worst thing at all to hear. That’s where we go as writers: to our laptops, to figure things out that can’t be figured out in other ways.

In writing this book, I’m sticking to true life. I know that we both enjoy writing strange and absurd fictions, too, but how close to life do you actually write within those forms?

RR: My beat on the page is big sadness and high strange, but my life is relatively even-keeled with occasional bouts of joy. Like so many jobs, the scourge of email is omnipresent in my day job, and I spend seventy-five percent of my working hours firing off little notes into the ether, which doesn’t make for the best creative fodder. Still, like you said, my worldview aligns with the absurdists. Uncertainty is the only certainty concerning our true place and purpose in the universe, and I suppose the search for meaning is really the only thing I ever write about. That is all to say: I write close to my intellectual experience of the world. But, like Emily Dickinson said of her poetry: I am not the I.

How about you? How close to life do you write when you’re working in other genres?

AMF: You know, oftentimes I really am the I. Maybe it’s a selfish impulse, but when I’m most invested in the writing process, I’m dialed in, worked up, a little bit obsessed. I return to a lot of the same topics: family, jobs, romance, violence, power, womanhood, dreaming. I think it’s because those things speak to me in a deeply personal way. So, even when I have a specific character or speaker in mind, there’s a little bit of myself tangled up within that perspective or voice. I’ve never been successful at beating back that impulse.

Speaking of where we show up in our written work, how was it reading drafts of this book, given you were involved in the actual events? It’s not like you could be objective necessarily. Or could you?

RR: In an old Paris Review interview, Hemingway famously said, “The most essential gift for a good writer is a built-in, shockproof, shit detector.” I think we’ve both developed pretty decent detectors when it comes to seeking and destroying our own cringey writing. In fact, when I was reading drafts of Dear Damage, I didn’t see anything cringey at all. The main thing I helped you think through was the structure.

In terms of the events of the book, you write about tough topics like love and loss with an unassuming power and grace. In many ways, it’s a lot tougher to write about love than it is to tackle loss. You write love well, which isn’t easy. It’s like writing a happy song. There aren’t many good ones. “Heroes” by Bowie and “I Got You (I Feel Good)” by James Brown come to mind, maybe also “Good Vibrations.” It’s a short list.

AMF: Maybe a few songs by The Beatles or Prince? But yes, you’re right. And thanks for saying that. Yes, love is much harder to do well. And it’s funny you mention “cringe” because I think that’s what we most count on each other for when we read each other’s drafts—is there anything regrettable here? Anything uncomfortable in the bad-uncomfortable way? It’s great to have a reader (to live with a reader, no less) tuned to the same channel about these things.

Alright, I’m setting myself up here, but how did I do writing about you?

RR: Oh, you did great! I’m flattered by what you’ve written. But, if you’ll recall, the only reason I’m even in the book is because your editor said, “Forty percent more Ryan.” In the early drafts, I was more of a mysterious cipher. I had one line. I said “I don’t know” at a grave moment. However, after the me mandate, I got a lot more page time. The editorial wisdom of including our love story opened things up and made the book a lot less of a bummer. It added the necessary contrast.

AMF: I’m forever grateful for that genius advice my editor gave me. And actually, I think there’s maybe 400 percent more of you, which does indeed improve the book.

Have you ever written about me?

RR: Yes, often, but always in various guises and disguises.

AMF: Most of what I write about you is also explicitly about love, which, as I mentioned above, I don’t write about often. I actually think you do more of that, in your own way. Can you talk about the role of love in New Bad News and Ox and other books of yours?

RR: Yes, guilty as charged. I write a lot about love or the lack thereof in my work. I also write about history and death, friendship and fate, and many other classical themes—but what else is there? Music, maybe. Speaking of, you incorporate a lot of music in Dear Damage. Can you talk about the role of music in your book/life?

AMF: Well, music is a big part of the life you and I share. It’s woven into our day-to-day and seeps into our writing lives. I also listened to a lot of music as I wrote this book: specific songs on repeat as I typed that I’ll now forever associate with Dear Damage. But I think music plays a role in this book because it’s been so important to my family. In some of the transcripts, my grandparents talk about songs of their era, or seeing Desi Arnaz, Jr. or Gene Krupa play in Los Angeles. Other songs I can remember my mom or dad singing around the house when they were cooking or doing chores. Plus, music is so tied into memory, almost inseparable from it. Just flashing on all the times I drove around in the 90s with my best friend conjures an entire playlist. In some ways, sound is as important as visuals when I recall the past.

Same for you! How does music fit into your work/world?

RR: Music is as essential as air, yes. If I’m not writing, I’m listening to music or playing it. And there’s nothing like a familiar song to transport you to a time and place. Certain songs I can’t even hear anymore because they only remind me of where I was and who I was when I first heard them. Speaking of time traveling, your writing is kaleidoscopic. Time and place function in a different manner during this time in our lives. Your book kind of smashes time or is quantum in the leaps it takes. There’s a chronology, but it’s not linear. Why didn’t you structure this in a more traditional way?

AMF: The book’s chronology was a puzzle. I knew this wasn’t a beginning-to-ending kind of project, that it wasn’t a linear story of three generations. I also knew I wanted it to be compressed, short, to pack a punch. I wasn’t interested in drawing things out. Plus, trauma and grief smash time up, warp it. Losing someone means revisiting moments or conversations you shared with them, often out of order and at seemingly random times. So, I kind of embraced that shattered-ness of time, memory, love, experience. What I let guide the structure instead was the circular nature of things, the looping and repetition of events—like marrying more than once, attending grad school more than once, encountering you at different moments in time, moving to California after my parents and grandparents had left. That recursiveness is more true to how I experience life: waves crashing, pulling back, crashing again, on and on.

Speaking of time and place: I love reading your work and seeing reflections of places where we’ve lived together, or our hometown of Louisville. Can you talk a little bit about the role place plays in your work?

RR: A place gives rise to the spirit, which is particularly true concerning Kentucky. It’s like the two-time governor of the bluegrass state, Happy Chandler, once said: “I’ve never met a Kentuckian who wasn’t either thinking about going home or actually going home.” I’ve spent a lot of my adult life in the West, and, for me, writing about Kentucky is a homecoming of sorts. I travel there often in my mind. But Southern California, specifically Los Angeles, occupies the most real estate in my creative imagination. It’s a place I return to again and again. In fact, the novel I’m working on right now is set there. Like Raymond Chandler, I have mixed emotions about the place, but that tension continually inspires me to write about it.

Last question: what are you working on now that Dear Damage is done? What’s next?

AMF: Well, while you were working on this interview the past hour or so, I was trying my hand at the next 1,000 words of a novel. I’m also working on some essays about the human heart. I’m hesitant to write those things here out of superstition, but here we go! When I get a little further along, I’d love for you to read some of what I have so far, if you wouldn’t mind.

Ryan Ridge is the author of four chapbooks as well as five books, including the story collection New Bad News (Sarabande Books, 2020) and the poetry chapbook Ox (Alternating Current, 2021). Ridge has received the Italo Calvino Prize in Fabulist Fiction, the Linda Bruckheimer Prize in Kentucky Literature, and the Kentucky Writers Fellowship for Innovative Writing from the Baltic Writing Residency. His work has been featured in Denver Quarterly, Moon City, Passages North, Post Road, Salt Hill, Santa Monica Review, and Southwest Review, among other outlets. He is an assistant professor at Weber State University in Ogden, Utah, where he codirects the Creative Writing Program. In addition to his work as a writer and teacher, he edits the literary magazine Juked. Ridge lives in Salt Lake City with the writer Ashley Farmer and plays bass in the Snarlin’ Yarns. He’s working on a novel.

More Interviews