I first read Rodrigo Fresán in 2011, when my twin brother—one of the best readers I know, responsible for introducing me to many of my favorite writers—gave me a copy of Kensington Gardens, in Natasha Wimmer’s masterful translation. At the time, I was more familiar with Wimmer than with Fresán, having devoured her various Bolaño translations, and having only seen Fresán’s name in passing in one of those translations (Between Parentheses).

Reading Kensington Gardens was the kind of epiphany that only comes a reader’s way once in a great while. It felt both familiar and entirely new, reminding me of (U.S.) American maximalists like Thomas Pynchon and David Foster Wallace but filtered through a sensibility at once Argentine and not, like a kind of lysergic Borges, untethered from the short-story form, swept up in the raucous winds of ’60s and ’70s rock-and-roll and the global explosion of television. I found such pleasure in the capaciousness of Fresán’s mind and the velocity of his free-wheeling style, untroubled by narrative convention yet fully capable of pushing all the right buttons, offering up an arresting combination of head and heart, of pathos, formal playfulness, and humor.

Suffice to say, I was hooked. Yet I was surprised to find that none of Fresán’s other fiction had found its way into English. I quickly got my hands on the Spanish editions and dove right in. Not long after that, I was taking my first stabs at literary translation and, in preparation for starting the MALTS (Master of Arts in Literary Translation Studies) program at the University of Rochester, I started to translate El fondo del cielo [The Bottom of the Sky].

I had no expectation that my translation would ever be published. For me, it was just an opportunity to practice and reread a book I loved. Little did I know that a few years later—through some fortuitous alignment of stars: an indulgent author, a trusted mutual friend, and a generous publisher willing to take a chance on a neophyte—not only would that translation be published, but I would be more than halfway through translating Fresán’s career-defining trilogy.

One of the great pleasures of working on these translations has been getting to know their author. From the beginning, Fresán responded quickly and good-naturedly to any query I sent his way. Over time, our correspondence expanded beyond the translations themselves to include book recommendations, rehashing episodes of Twin Peaks: The Return, new Philip K. Dick adaptations, or the latest installment in the Marvel Universe. As we got to know each other better—meeting in person for the first time in Barcelona just before the U.S. publication of The Invented Part in the spring of 2016—we became confidants. When, in 2017, my partner and I were in Barcelona so she could present a paper at the Latin American Studies Association conference, Fresán invited us to stay at his house. When, later that summer, my cat died unexpectedly, he recommended I read William S. Burroughs’s A Cat Inside, a recommendation that turned out to be incredibly healing and that I still find both moving and characteristically Fresanian.

Whether sipping Mantras in Barcelona’s Belvedere, zipping through Manhattan bookstores in search of a gift for his son or some rare edition of Transparent Things, or sharing a stage at a reading, I’m always struck by Fresán’s disarming wit and kindness. He draws you into his universe with the same encyclopedic knowledge and expansive generosity readers of his fiction know well, telling stories of random celebrity encounters, raving about favorite books and movies, taking jabs at the literary establishment, always making high-speed connections, always with a twinkle in his eye and a healthy dose of irony.

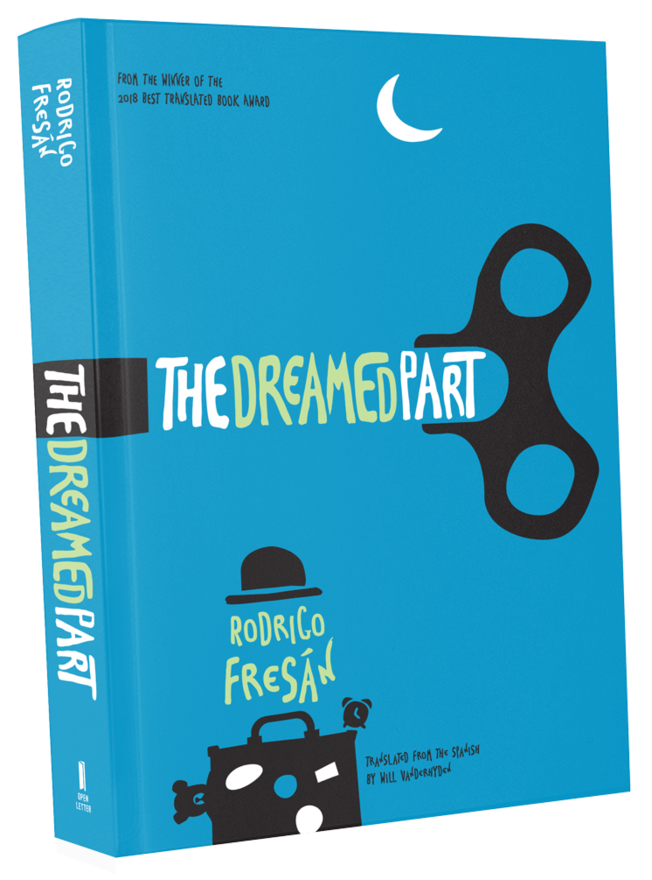

This interview was done over email in advance of the U.S. publication of the trilogy’s second volume, The Dreamed Part, and the Spanish publication of the final volume, La parte recordada [The Remembered Part]. The Dreamed Part—a book I’m now intimately familiar with, having read its pages countless times while morphing it into English—follows Fresán’s narrator, The Writer, through a long insomniac night of serpentine digressions and waking reveries, picking up the narrative threads of The Invented Part and weaving a new kind of tapestry, replete with Fresán’s characteristic humor, formal playfulness, and referential mania, reprising roles for Penelope and the Karmas, key cameos by Emily Brontë, Vladimir Nabokov, and Bob Dylan, and revelations that will bring readers closer to the dark secrets at the heart of the story and the narrator’s sleeplessness. I’ve only now finished reading La parte recordada and will soon begin its translation; it strikes me as the perfect culmination to a trilogy described by the French paper Le Figaro as “a UFO that will probably make history” with “echoes of the best novels of Thomas Pynchon and William Gaddis.” For me, that pretty much sums it.

Will Vanderhyden: John Cheever said, “When you finish a book, whatever its reception, there is some dislodgment of the imagination. I wouldn’t say derangement. But finishing a novel, assuming it’s something you want to do and that you take very seriously, is invariably something of a psychological shock.” You’ve said in the past that when you were writing and even after finishing The Invented Part, you weren’t planning on it being the start of a trilogy. When did you realize it would become a trilogy? And now that you’ve finished the third volume, The Remembered Part, how dislodged is your imagination? What’s the psychological shock that accompanies finishing this nearly two-thousand-page, three-headed monster?

Rodrigo Fresán: The feeling is a mix of relief and pride and of having completed a particularly difficult mission. Probably the most complex of my career and something that will be hard for me to attempt or take on again. The kind of “gesture” (as my friend, the writer Alan Pauls, described it) only attempted once in a lifetime. Also—and this wasn’t part of the plan and I still don’t accept it as real—a palpable sadness due to the fact that my editor and great supporter of the project, Claudio López de Lamadrid, passed away suddenly and unexpectedly at the beginning of this year. Claudio is the not-so-secret hero of this trilogy, which, no doubt, would not be what it is, without his encouragement and tolerance for this kind of undertaking. As you say, there was no intention/ambition initially to do a trilogy: The Invented Part, in the beginning, began and ended in itself. But once the book was finished and published, I discovered that it was very hard for me to let go of its “voice,” its screams as well as its whispers. And so, I found myself adding inserts (nearly sixty additional pages, in the end, that had to be incorporated into the pocket edition and into its translations, so far into English and French and Italian). And yet, even still, I didn’t feel the story had been told in its totality. Also, of course, I wanted to get to know/let others get to know Penelope better. And so, what I first conceived of as a novella about two children and one adult walking through a phantasmagorical city that could well be Buenos Aires ended up turning into a handful of fateful pages in The Dreamed Part.

WV: You don’t strike me as a particularly cynical or resentful person, but The Writer, your trilogy’s protagonist/narrator—whose life and career track parallel to your own in many ways—is profoundly disillusioned, obsessing (sometimes despairingly, often hilariously, always with a healthy dose of irony) over the rise of technology and the facile, fickle, and opportunistic nature of a literary world that no longer has time, space, or attention span for a writer like him. Is The Writer your alter ego—the Mr. Hyde to your Dr. Jekyll—or just a useful foil? Do you find a particular freedom in this device, this voice?

RF: That’s it: a virtual Mr. Hyde. A Hulk. Part of what was “fun” in writing these three books was deciding which things and subjects—mobile phones, autofiction, etc.—would bring the protagonist to the brink of the most resentful madness. It’s clear that he’s not me (and that I’m much happier, and so that’s why I give myself cameos in the books, to make that even clearer to the reader), though we do share passions (Bob Dylan, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Vladimir Nabokov) and phobias. Sometimes I enjoy thinking about a variation of the aria that is me—a kind of multiverse à la Marvel Comics—but with the volume turned up to eleven. I’m usually playing at somewhere between six and seven. I am, I think, a good person, and I’m not that concerned with the splendors and miseries of the literary world. You could say that the things that drive my novel’s protagonist crazy and make him grind his teeth almost don’t interest me. Almost, I said.

WV: I’m glad you mentioned your cameos. They are subtle and playful and revealing in the best way, and, for an acute reader, they really give the lie to the idea that The Writer is just a lightly fictionalized version of you. There’s a moment in The Dreamed Part, where The Writer is describing his chance encounters with this other writer (you), and he says: “That guy he often saw at the supermarket with his young son and wife. That guy who looked like a Ringo Starr impersonator who’d been left outside overnight, but who, nevertheless, always appeared and seemed to feel so happy and satisfied; and the truth is, things weren’t going too badly for that guy or, at least, better than they were for him (and he spied on them from behind a column, a family, could that be the key, the secret? Could you write better being a husband and father or, at least, write something?). There he was: another foreigner. A foreigner like him and one who was born in the same place he was and who seemed to be everywhere, writing about everything he was interested in and about which he no longer wrote: another form of torture, another deforming-for-the-better reflection of himself, another perfected clone.” This description leads me to see The Writer in another light, as a kind of what-if for how your life might have ended up had you not had a family. Do you think that having a wife and a son has given you a certain perspective that keeps you from taking the vicissitudes of the literary world and your life as a writer too seriously?

RF: Yes. That’s how I am. That’s me. That’s me. That’s me. And, yes, the (positive) influence of a stable partnership/paternity is more than obvious and beneficial to/for my work. To begin with—in the case of the trilogy—because it was my son who discovered that antique toy and demanded/designed its appearance first on the cover and, a minute later, as protagonist/symbolic talisman for the whole endeavor.

WV: You’ve describd the way The Invented Part was constructed and composed: a different text for each day of the week; seven nonlinear, synchronous sections that—like a multitrack recording—you overlaid and and juxtaposed into a harmonious whole. How did you come up with The Dreamed Part’s structure?

RF: It was simpler (freer) and at the same time more complex: I tried to make it have something of the liquid structure of dreams. Not the simplest thing (like what also happens with sex scenes) to put in writing. Near the end of the book, it’s pointed out how the book’s three “movements” function: “The first movement, that of the dream; the second, that of the waking dream (where you don’t know if it’s headed toward falling asleep or waking up, toward understanding or not understanding what happened); and the third, that of eyes wide open, forcing you to see everything you wanted not to see for so long. Dream, waking dream, dreamless.”

WV: And then, can you talk about how you conceived of the overall structure of the trilogy? All three books have, generally, a three-part structure, but if we consider the whole as a single novel in three parts, was there a preconceived, overarching vision unifying the disparate parts, or did it just emerge organically as you wrote?

RF: The structure is something that came together on its own. The truth is, I work in a fairly intuitive way, as if I were reading myself, wondering what might happen on the next page. There are, of course, clear points and more or less solid certainties. But it was only when writing The Remembered Part that I knew/wanted not just to bring the trilogy but all of my previous books to a close here as well. It’s a kind of Avengers: Endgame, ha!

WV: In The Dreamed Part, the subject of dreams is the impetus, the engine driving the narrative. And yet, it’s the twin waking nightmares of writer’s block and insomnia—the simultaneous loss of sleeping dreams and creative inspiration—that occasion The Dreamed Part’s narration. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I can’t imagine you ever suffering writer’s block. Insomnia, though, is that something you dealt with while working on this book? If so, did you try any of the litany of treatments—from various drugs to Max Richter’s Sleep to sensory deprivation, to name just a few—that The Writer attempts in the pages of The Dreamed Part?

RF: It’s true—never writer’s block but just the opposite, which can end up being just as paralyzing: an abundance of ideas and possibilities shooting off in all directions at the same time. And, yes, while writing The Dreamed Part, I did suffer a powerful insomnia (actually my deep sleep was ruined forever in my youth during my obligatory military service), which I battled in every way possible. What finally broke the unbearable loop was a combination of hypnotics (for a week) and homeopathy.

WV: In the final pages of The Dreamed Part, The Writer describes a book that might well be the book we’ve been reading like this:

A book with all times at the same time, which, when seen all at once, produce an image of life that’s beautiful and surprising and deep. There’s no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no cause, no effect. Nothing but marvelous moments, where invention is the control, dreams the entropy, and memory somewhere in between, somnambulant and ambulating through what’s created while awake and what’s thought while asleep.

A book in three movements.

Slow motion music.

Aside from loving this description, I’m fascinated by the idea of this book as “Slow motion music.” Musical references are nearly as integral to your fiction as literary ones. You’ve talked about growing up immersed in ’60s pop music, about how your referential mania—a defining characteristic of your style, the collaging of literary and pop-culture references—may well have been born of your first encounter with the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and about how the song “A Day in the Life” gave you a new template for how narratives could be structured. You incorporate song lyrics into your prose and turn famous musicians into characters, but what about this idea of The Dreamed Part as “Slow motion music”: Is it about the structure? The musicality of the prose? Where does this idea come from?

RF: A good part—the first part—of the paragraph in question is just a rewrite of one of my favorite moments in the whole of my reading history, in one of my favorite books now and forever: the description of the extraterrestrial and Tralfamadorian books in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five. The cover of Sgt. Pepper’s is the innocent culprit when it comes to my referential mania, and, there inside, “A Day in the Life” has helped me understand a certain kind of narrative structure that worked for me, as someone incapable of deploying conventional forms of storytelling. The trade’s great secret comes down to finding a way to turn your defects into virtues. Maybe the best possible example of “slow motion music” is what Pink Floyd achieves in the suite “Shine On You Crazy Diamond,” but, also, much of what David Lynch—perhaps the greatest waking dreamer of our time—manages to turn into images.

WV: Mariana Enriquéz says: “Places are characters to me.” And: “Argentina is a theme and a character in my stories.” I’m interested in how you conceive of place in your fiction. Unlike Enriquéz, you don’t often go into detail describing physical settings, but certain places recur throughout your work. Sad Songs—a place that is given an origin story in The Dreamed Part—with its shifting locations and various incarnations being the most obvious example. Do you think of places as characters, as motifs, as states of mind?

RF: I agree with Mariana when it comes to the idea of places as characters. In that sense, Sad Songs is one of my most complex and polymorphous and perverse characters. Although, maybe, now that I think of it, my places are more ideas than characters. I like to imagine my “places” as states of mind or, if you prefer, states of the non-union.

WV: To the extent that your characters are grounded in physical reality, they are almost always in liminal spaces, spaces of transition, of perpetual motion: airports, airplanes, funiculars, trains, hadron colliders, beaches (“the place where the forest ends so the sea can begin”), the Widest Avenue in the World, even a steampunk-style bed on a system of rails. Is putting your characters—and by extension your readers—in motion a sort of meta-metaphor for the acts of reading and writing? Is literature necessarily a journey to you?

RF: Of course. Without a doubt. I agree completely. That’s why nothing intrigues and irritates and even terrifies me more than all the people who don’t read. And who, for that reason, never really move, because they understand movement as nothing more than the minimal yet crucial act/journey of breathing.

WV: You’ve talked about how your books are not somewhere to go live, but something that comes to live with you. Can you unpack that distinction a little bit?

RF: I would say that your books are like the members of your family that you get to choose. Which doesn’t remove the possibility that some of them (at least in my case) are completely crazy.

WV: There is an old maxim in American (U.S.) writing workshops that goes “show, don’t tell.” The idea being that action/event/exteriority should drive narrative. Your work actively resists this idea. In your trilogy, you write around key events, teasing them out slowly, obliquely, only rarely narrating them directly. External action is often an afterthought, implied or slipped underhandedly. The real action in your books is something more fundamental: a hyperactive, bibliophilic, referential-maniac mind at work and at play, in the act of creation. The showing is in the telling, in the style, in the show of the telling. Do you think there’s any wisdom in this idea of showing rather than telling, or is it a false dichotomy?

RF: I try—the wordplay is worth it—to pay minimal attention to certain maxims that seem, all the time, to demand your attention and obedience. I suggest that everyone do whatever they like and whatever works best for them. I like books—I’m thinking of books by authors like Proust and Nabokov and Banville and Vila-Matas and a good part of Cheever—that take place inside their authors’ heads. And it’s well known how little is known about what actually takes place inside someone’s head and why it takes place and why that takes place inside a given head. Personally, I think of writing as a journey into the depths of the mind (of my mind). And, once there, you read it. And then put it in writing.

WV: You’ve described the point of view you use in the trilogy as “the most first of third-persons.” It is a unique perspective and, in some ways, reminds me of the so-called “brain-voice” of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, but it’s more internal, less third-person, and with access to the minds of fewer characters. Can you talk about where this point of view, this voice, came from and whether you think it has any literary precursors?

RF: I suppose it’s a variation of the same melody sung by the voices I mentioned in the last answer. I always keep very much in mind what Joan Didion once said—I think it was in her interview in The Paris Review— about “playing with a close third person” when it comes to getting “something down” about someone, clarifying that “by a ‘close third’ I mean not an omniscient third but a third very close to the mind of the character.” The idea/necessity that it be in third person also had to do with not collaborating with those who, inevitably, tend to think, for some time now, that EVERYTHING is autobiographical. Poor things . . .

WV: But there is also a splitting of the voice, represented on the page by a font change. The intervening American Typewriter has a further degree of mobility and omniscience—zooming in and zooming out, sometimes acting as the fact-checker, sometimes the counterpoint, sometimes like a ghost from beyond the grave—creating the effect of a dialogue or a harmony. Where did this intervening/harmonizing voice come from?

RF: Good question and if you come across the answer somewhere, I beg you to send it to me. I want to know it. Thinking about it a little, I suppose those interventions function something like brainnotes instead of footnotes. Again: one of the many ways to keep from relinquishing my status as a reader while writing.

WV: In an interview, Donald Barthelme talks about how parody can be used to inject philosophical potency into a text in a kind of nonchalant way, creating an unexpected, deeper kind of satire. In your trilogy, The Writer parodies the contemporary literary scene to hilarious effect. No one is spared: writers, readers, editors, reviewers, awards, festivals, roundtables all get their due. Not to mention The Writer himself. And, of course, most prominent of all is his ever-present nemesis IKEA: the ever-functional, ready-to-assemble, DIY, world-famous writer, his finger always on the pulse of the latest trend, ready to give readers whatever they want. Do you think, like Barthelme, that parody is a useful tool for gaining philosophical depth without having to be preachy? And: do you see much parody—or humor in general—in contemporary literary fiction?

RF: There is no true literature without genuine humor. The fallacy that serious literature must be serious in order to be so considered is, unfortunately, one of the great defects of our time. “Committed” is an adjective that gets on my nerves. Same goes for the whole “reflecting the concerns of one’s time.” Same goes for the supposed advantage of “realism” over “irrealism” (which might be a far more faithful reflection of the days and nights we have to live and suffer through).

WV: I think that, in one way or another, the concerns of one’s time inevitably filter into one’s fiction, but that what matters is how those concerns are presented or represented. That’s where the art or lack thereof comes in. Is it the sort of strict, Sartrean notion of “committed literature” or “committed writing”—prose (unlike poetry) as, essentially and necessarily, utilitarian, communicative, attached or reducible to a political ideal—that rubs you the wrong way? Does political commitment really have to come at the expense of aesthetics? Can’t there be both?

RF: Uh . . . To tell the truth: I never read Sartre. When it comes to choosing one thing or the other, I’m sure that a certain equilibrium can be found. In fact, I think I have done/achieved just that in Argentine History and Esperanto and in more than one section of the three Parts. Of one thing I’m certain: it’s impossible to do it without humor. But my principal commitment is to telling a good story. I leave History (supposedly with a capital H) to other people and good luck to all of them.

WV: When Jonathan Lethem was asked in an interview where his politics entered into his fiction, he responded: “In the hope that some fourteen-year-old kid in Milwaukee reads Amnesia Moon and is ratified in his suspicion that the government is television, that George Bush is the star of a rotten soap opera. That’s all I have to offer, what Philip K. Dick had to offer me, solidarity. My politics are everywhere.” I feel like you might have a similar response. In The Dreamed Part, The Writer offers the following: “Now, writing seems to be merely the prologue and they want you to be like a politician or a preacher and for you to offer an opinion about everything and I wonder if we aren’t betraying the basic idea of the whole thing: the mystery of creating an object that contains all the explanations for those individuals who know how to read them on their own, without needing us to go around from one auditorium to the next pointing them out, ringing our little bells, like leprous visionaries of the end of the world . . .” I wonder if you can comment on the relationship between the literary and the political. Is it, for you, about solidarity? Are your politics everywhere?

RF: Ditto to what Jonathan said. I don’t trust any kind of political dogma and much less politicians. And, yes, my contribution to society is to offer stories that are as well written as they can be or as well written as I can make them. The rest is sound and fury told by you know who, signifying you know what.

WV: Gaddis says, “trying to correct one’s ‘image’ is as futile as it is irrelevant.” You’ve made the distinction between the literary career versus the literary vocation, saying, “I like writing more and more but like the fact of being a writer less and less.” Is “the fact of being a writer,” having to promote and perform, to shape and correct one’s image or public persona, toxic for literature? Or does it just miss the point?

RF: The distinction I’m proposing—or, maybe, preaching with true evangelist zeal—is that what really matters is the work and not the life. The act more than the acting. And, yes, for me, there is something toxic in such temptations: the danger of a certain kind of material fatigue or that people will see you more than they’ll read you (and I’m convinced that what they’ll see can never be the best version of you; or, at least, it shouldn’t be).

WV: And yet, famous writers—and their historical personas—play a central role in your trilogy. The lives and work of F. Scott Fitzgerald, the Brontës, Nabokov, Burroughs, among others, are built into the fabric of these books. The writers—or your version of them—become like characters, a lens (sometimes as cautionary tale, sometimes as inspiration) through which to examine the act of literary creation. So is it about reading the life through the work or the work through the life? Or is it something else? How do you square this idea that what matters is the work and not the life with your own fascination with writers’ lives?

RF: I really like reading biographies of writers. They also seem to be very instructive. But, warning, when I consume them, I am, also, reading them. A good biography or autobiography is part of the work: think of Speak, Memory or The Crack-Up . . . Or The Journals of John Cheever or the diaries of Adolfo Bioy Casares about Borges . . . Or Kurt Vonnegut’s interruptions in his fictions. Or Brian Boyd’s biography of Nabokov or Barry Miles’s biography of Burroughs. Or Ricardo Piglia’s memoirs disguised as the diaries of his character/avatar Emilio Renzi . . . Or all of Proust.

WV: In your trilogy, you draw a parallel between the current strain of autofiction and selfie culture, between the superficial fiction of social media and what The Writer calls “the literature of the I.” F. Scott Fitzgerald famously wrote, “You don’t write because you want to say something, you write because you have something to say.” In the age of blogs, online forums, and social-media “stories,” it feels like maybe that distinction has been lost. And this confessional/testimonial impulse is “trending” in the literary realm too. The supremacy of the present tense and the first person, of diaristic realism, of a direct, unadorned style. But at the same time, the label autofiction can be applied to writers of myriad styles. Indeed, your own work or that of Enrique Vila-Matas or Roberto Bolaño might be called a kind of autofiction or said to contain autofictional elements.

RF: The small but definitive difference is, I suppose, that Bolaño and Vila-Matas and I write through alter egos, while so many others (I won’t name names) do so through . . . egos? Or, better, as I say in The Remembered Part, through “alert-egos.”

WV: In The Remembered Part, The Writer refers to the autofiction of alert-egos as writing “with training wheels,” as opposed to “look ma, no hands!” Can you expand on that?

RF: There is no risk, no danger of falling down. You never achieve the ecstasy of balance or an interesting speed. The alert ego has, I believe, a vocation closer to the selfie than the self-portrait. It presents itself as pure, faithful reality, which is why, clearly, it’s also pure infidelity to the idea that a writer’s job is to consider the real as primary material out of which to construct something else, something new, something that wasn’t there and in clear view of everyone and anyone. The narrator of my three Parts feeds off parts of me. But I never informed against my parents, causing them to be disappeared, nor did I have a delusional and best-selling sister. In fact, as I mentioned previously, my “true” self makes cameos in The Dreamed Part and The Remembered Part (nothing is random) alongside Vila-Matas in La Central, a bookstore in Barcelona (where my books are often presented). And one small but very important detail: the Parts’ protagonist feels particularly irritated and offended by this trend because he knows he has a great true story to tell, but to write it and publish it would mean his own social demise and a vilification from which there would be no coming back (the issue of autofiction—like so many other things that make my character howl, many of which I’ve employed in previous books and even in the Parts themselves, where they are denounced—doesn’t really concern me, it barely interests me at all). Bolaño and Vila-Matas and I—when it comes to them, I believe, and when it comes to me, I’m sure of it—think of our personas merely as points of departure and not the finish line. The same goes for Nabokov, who departs from his own spacio-temporal coordinates in The Gift or in Pale Fire or in Look at the Harlequins! or in that miracle of recreated biography and selective memory that is Speak, Memory, and look at where he ends up going: to infinity and beyond. I’m not interested in knowing what autofictional narrators ate for lunch, but I am interested in knowing how those proteins act on their brains. But also, to be fair, it seems to me that the problem doesn’t really come from the writers who practice such radiographic and extreme autofiction (everyone has the right to do whatever works best for them), but from the type of readers this kind of practice has created, readers who—in a somewhat narcissistic and sinister way—see their daily tweetinstagramfacebooking habits reflected in print and between the covers and thereby feel “literarily” justified in their constant exhibitionist exposition and, in more than one instance, in too many instances, justified in writing an instant memoir about everything they did that morning and in thinking there’s something in it that’s not only interesting but worthy of everyone’s attention. Again and once more Nabokov: “Reality is overrated.” And more Nabokov—if he said it, I could never say it better—from his lectern in some American university: “Literature is invention. Fiction is fiction. To call a story a true story is an insult to both art and truth. Every great writer is a great deceiver, but so is that arch-cheat Nature. Nature always deceives. From the simple deception of propagation to the prodigiously sophisticated illusion of protective colors in butterflies or birds, there is in Nature a marvelous system of spells and wiles. The writer of fiction only follows Nature’s lead . . . Then with a pleasure which is both sensual and intellectual we shall watch the artist build his castle of cards and watch the castle of cards become a castle of beautiful steel and glass.” Ditto, Gloria Mundi, Hallelujah, Amen.

WV: As someone who translates from Spanish, and knowing you to be very well read in contemporary Spanish- and English-language literature, I can’t help but wonder what you think about the work that’s coming into English from Spanish these days. There’s definitely been an uptick in recent years in terms of the number of books, but do you think English readers are getting exposed to the best books being written in Spanish?

RF: Hmmmm . . . Hard to say. My favorites are mine, and there’s no reason they should be anyone else’s. It’s clear that more is being translated, but this new, small profusion often does little but further highlight the great absences. My advice to the USA/UK reading public is that they do what I once did in the opposite direction: study and learn Spanish. But in the meantime it’s more than worthwhile to celebrate the multiplication of made-in-the-USA publishers who audaciously take on foreign work and find good translators (I can’t help but feel a certain strangeness being interviewed here by the author of my book in English). When it comes to me, I have to say I’ve been very lucky in terms of the sustained effort and enthusiasm of my editors and translator at Open Letter.

WV: Early in The Remembered Part, you refer to a quote by Jean Rhys: “All of writing is a huge lake. There are great rivers that feed the lake, like Tolstoy or Dostoyevsky. And then there are mere trickles, like Jean Rhys. All that matters is feeding the lake. I don’t matter. The lake matters. You must keep feeding the lake.” To your mind, who are today’s great rivers? Who are mere trickles? Is the lake being well fed?

RF: Again: something that I find oceanic may be the mere drip of a faucet in the middle of the night for someone else. And it doesn’t seem fair to me to apply temporal coordinates to the eternal. So, for me, there’s no one more present and modern than certain writers without whom I wouldn’t be the kind of writer I am. There I go again: Adolfo Bioy Casares, John Cheever, Vladimir Nabokov, Marcel Proust . . . and so many others. When it comes to possible trickles, the truth is I haven’t been drinking from those waters for a while now. At one point, I did so out of pure curiosity and to find out what the trendy drink was. But to tell the truth, they always left me thirsty. So I’ve returned to my habitual oases and farewell to all those mirages. ![]()

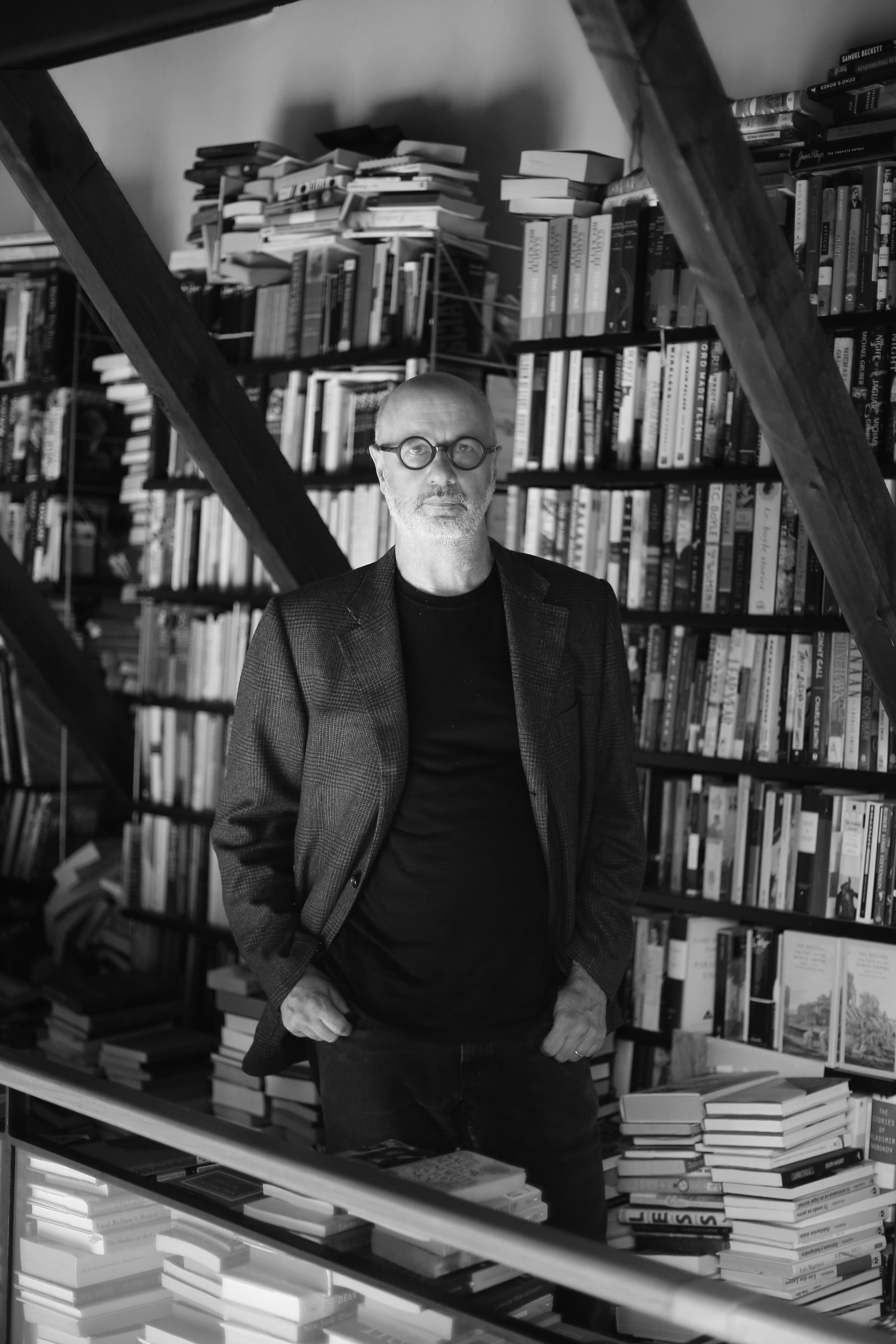

Will Vanderhyden is a freelance translator, with an MA in Literary Translation from the University of Rochester. He has translated the work of Carlos Labbé, Rodrigo Fresán, and Fernanda García Lao, among others. His translations have appeared in journals such as Two Lines, The Literary Review, The Scofield, and The Arkansas International. He has received fellowships from the NEA and the Lannan Foundation. His translation of The Invented Part by Rodrigo Fresán won the 2018 Best Translated Book Award.

Rodrigo Fresán was born in Buenos Aires in 1963 and has lived in Barcelona since 1999. He is the author of the books Historia argentina, Vidas de santos, Trabajos manuals, Esperanto, La velocity de las cosas, Mantra (Premio Nuevo Talento Fnac 2002), Kensington Gardens (Premio Lateral de Narrativa 2004, finalist Premio Fundación José Manuel Lara), The Bottom of the Sky (Locus Magazine Favorite Speculative Fiction in Translation Novel 2018, USA), and of The Recalled Part triptych, comprising The Invented Part (Best Translated Book Award 2018, USA), The Dreamed Part, and The Remembered Part. In 2017 Fresán was awarded the Prix Roger Callois in France for the entirety of his body of work.