The first time I encountered Carmen Boullosa’s work was in January 2006, when Words Without Borders’ managing editor wrote to me in a panic: a translator had flaked on delivering an excerpt from Carmen’s recently published La novela perfecta, a sci-fi novella about a washed-up writer who meets an inventor and “writes” his book with a new technology that transcribes the book directly from his imagination. It was completely unlike anything I had ever read, and I was hooked after the first page; it was a tight deadline but I said yes.

A few months later, Carmen asked me to translate an excerpt from her latest novel, La otra mano de Lepanto (which the magazine Semana rated one of the 100 best works of Spanish-language literature written in the past twenty-five years) for the PEN International Congress in Berlin. I took a look at the text, which is a playful tale about a sword-wielding, flamenco-dancing heroine during the tumultuous era of Cervantes, when the Catholic and Ottoman empires clashed. The language of the novel is baroque, in keeping with its setting, and the translation was a trial by fire. I kept in close contact with Carmen as I worked on the translation and was tremendously relieved when the final product passed muster with her husband and first reader, Mike.

Over the years that followed, Carmen entrusted me with a variety of work—reviews, poetry, the introduction for a monograph, a screenplay. Each piece instructed me in the work of a new writer or cultural figure, from the writer Carlos Montemayor to the printer Juan Pascoe. I learned the nuances of her Spanish as she learned the nuances of my English, and we developed confidence in each other, much as lovers do. I built up the courage to ask her the difficult questions about things I didn’t understand. (Why did the protagonist of La novela perfecta call his wife Sara “Sariux”? He was employing a suffix of endearment that spouses use in Mexico City.)

The year 2013 represented a turning point in Carmen’s career and in mine as a translator, too. Will Evans founded Deep Vellum in Dallas and made an offer for Carmen’s 2012 novel, Texas: The Great Theft, which became his first title. It is a long novel featuring over 200 characters, and to meet Will’s deadline I raced through the translation à la méthode Rabassa (without reading the novel first). When I completed it, Carmen and I Skyped for hours, reviewing the translation and its challenges (we struggled especially with the corridos, the campfire songs the Mexican cowboys sang, trying a number of solutions that failed to varying degrees).

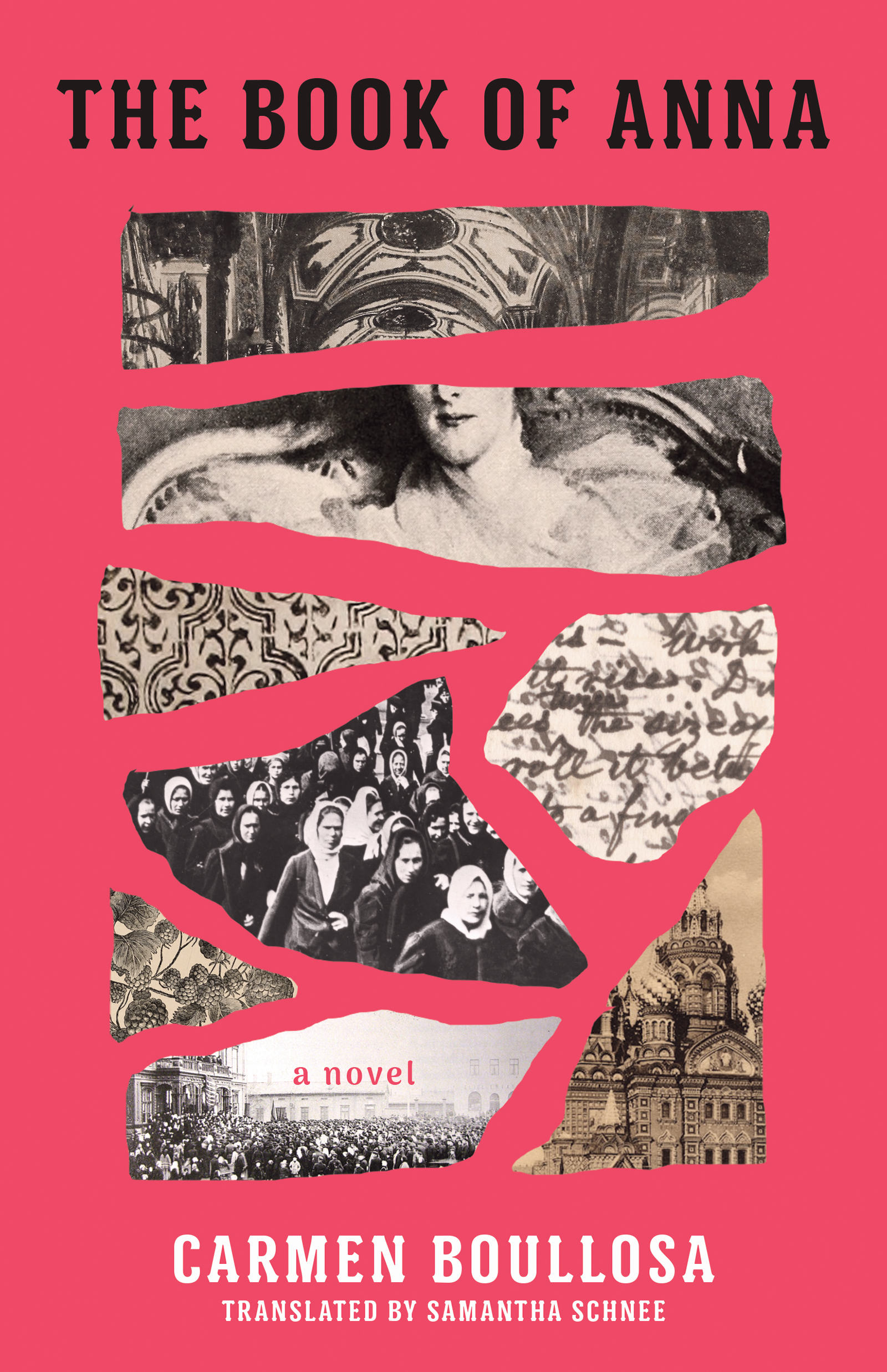

Throughout our correspondence, Carmen continued to teach and to write, producing El libro de Ana in 2016. The Book of Anna is the novel that Anna Karenina wrote before she committed suicide. Tolstoy mentions this book in passing toward the end of his novel; he just drops the fact that she’s written a novel but never says anything about it. So Carmen wrote Anna’s book—a grown-up feminist fairy tale—and hid it in the attic of the Karenin Palace, where Anna’s son, Sergei, lives with his wife and his younger half-sister, Anya (Anna’s daughter with Vronsky). Like a matryoshka doll, the discovery of this manuscript is set inside the story of the birth of the Russian revolution, which is every bit as tragic as Tolstoy’s novel.

I was particularly excited to work on this translation because Anna Karenina is one of my three favorite books. I’ve often wondered whether Tolstoy chose his protagonist’s name based on the prophetess Anna in the Bible. So later that year I applied to the Arvon Foundation for a translation residency at Lumb Bank, the Yorkshire home of Ted Hughes. It was there that I completed my translation of The Book of Anna, on a silent, snowy day when the world awoke to learn that Trump would be the next president of the United States (an event that has led to another collaboration, Let’s Talk About Your Wall, a brainchild of Carmen’s that will be published by the New Press this fall).

As Carmen imagines it, the book Anna Karenina wrote is “an opium-infused fairy tale” featuring a girl who is born into poverty in the woods and is taken from her parents by a magical woman who raises her alone in a palace. Naturally the girl goes exploring and finds all sorts of curiosities and treasures in the woman’s home, including beautiful artwork, precious books, and a genie in a bottle. It’s the Arabian Nights meets the Brothers Grimm.

If I had a genie in a bottle, like the one the protagonist of The Book of Anna finds on a bookshelf in her enchanted castle, I’d ask said genie to find an English-language home for three of Carmen’s novels:

First: La novela perfecta, which remains untranslated in full. How can that be? It’s The Perfect Novel!

Second: El complot de los Románticos, which, according to critic Christopher Domínguez Michael, “concentrates all of Boullosa’s talent; it’s the book where her two natures most harmoniously coalesce.”

And last but not least: Carmen’s latest novel, El libro de Eva, which tells the story of Genesis from Eve’s perspective.

Until I find that genie, I’ll have to content myself by working with Carmen on other projects . . . and by offering the following interview.

Carmen, since your work is often intertextual, harkening back to the work of our literary forebears and utilizing historical figures, I thought it would be interesting to ask you questions popularized by another historical literary figure, Marcel Proust. I’ve opted for the shorter, purist’s version here (the one that Proust himself answered in 1886 and again in the early 1890s) but have added a literary twist of my own.

The Proust (Schnee) Questionnaire

1. Your favorite virtue (in a character)?

My favorite virtue in a character is duality. I prefer characters who are just as appealing as they are irritating, whom I both like and dislike—especially if they’re being written by me. When I wrote my pirate novels (in the early nineties, one translated into English by Lee Chambers as They’re Cows, We’re Pigs, published by Grove), I remember feeling puzzled by the source of their magnetism, why I couldn’t resist them. My earlier novels all have young girls as the main characters; in the late eighties I once said in an interview that I could never even create a male character. Back then I had two small children, lived in a beautiful house with a garden that had trees growing figs, pomegranates, and bananas. My dog’s name was Conrad, my son’s was Rulfo, I had lots of friends and no economic problems (we owned a successful theater-bar), and there I was writing about these scoundrels! I knew I wanted to explore what had gone wrong with the first socialist commune in the Americas (the Brothers of the Coast), but I could have told that story from another point of view instead of telling it from the point of view of Alexandre Exquemelin, “the pirate’s surgeon,” and his circle. What was it about those pirates that attracted me? As I explained above, now I understand why: they were both appalling and wonderfully fascinating.

It was the same with Juan Nepomuceno Cortina, the “hero” of our novel (yours, Sam, and mine, because you translated it) Texas: The Great Theft. He’s as abusive as he is noble, he’s destructive and creates problems just as much as he helps people, he’s a man of contrasts, that’s how he was born to me. It’s not just chiaroscuro; these stark contrasts exist within him. That’s why I like him so much.

2. Your favorite qualities in a man (character)?

For a male character in a book, I love beauty and indecisiveness (such unmasculine qualities!); and though you haven’t asked, in a real man it’s intelligence, without question.

Now, there are qualities I find attractive (or that I prefer) in my own characters—if they don’t have them, they’re completely forgettable. The narrator and protagonist of La novela perfecta, for example: he’s written an international bestseller, he’s easygoing, but he doesn’t have the heart to start writing again after his huge success. He’s stagnating in his next book; it’s not his masterwork but it just might be better than the one that brought him fame and fortune. He lacks a rich interior world, he’s not pursued by powerful ghosts like great writers are, he just wants to write a nice story to please readers, which does not a “great” or “real” writer make. I can’t stand him.

On the other hand there’s a male character in my novel El complot de los Romanticos who has the curiosity of a true artist: Dante. But he’s portrayed as vulnerable and fragile because he’s been transplanted to the twentieth century, an environment that’s completely alien to him—that intrigues me. I don’t know whether my attraction to vulnerable male characters has anything to do with my being a woman. I have no interest in the macho-powerful-handsome-entitled-world-ruler stereotype, unless that becomes a weakness. Maybe that’s why I like the male protagonist in Adolfo Bioy Casares’s La invención de Morel, a fugitive who falls in love with a ghost (by the way, Borges called it a “perfect” novel).

3. Your favorite qualities in a woman (character)?

Courage or fearlessness. Though, as Bioy Casares said to me once in an interview long ago, “I think my interest is not in characters, but something else.” Bioy focused on plot, and Borges was more interested in intellectual adventures. Like them, I play with my characters like pawns—to create atmosphere and to render the no man’s land between drowsiness and sleep.

4. Your chief characteristic (as an author)?

The same as my favorite qualities in a female character: fearlessness and courage. And one more: craziness. I have other characteristics, too: if I don’t write, I’m not alive—life passes me by without that sensation of blood pumping through my veins. I’m always writing something; I don’t know how not to write. I also frequently use the work of other authors, both literary and otherwise. Writing and reading aren’t two different activities for me; I’m always referencing, asking myself questions, and searching out different perspectives. Though there comes a time, a state, when I’m writing a novel in which I can’t read another author’s prose, so instead I read poetry insatiably, maniacally, almost without reading it, to be honest, as if it were music, or a mantra, like praying the rosary all the way through without stopping. I skate over the verses of authors I know to fulfill a need, I think it’s an auditory one—I need to hear the sound in my ears; I try to disregard the meaning of the poems, they’re just music that washes over me.

5. What do you appreciate most in your translators?

That they can both write and comprehend the different levels of a text. That they have innate curiosity and patience. And something else: the development of a sense of intimacy between us that always makes me feel a little prudish (you feel immodest working with a translator because you always feel exposed, naked). The only solution is friendship. So I suppose I’d say that the thing I value most in a translator is that we become friends and they don’t betray me, which is the least you can ask of your friends.

6. Your main fault (as an author)?

It’s the same as my chief characteristic. Fearlessness.

7. Your favorite occupation (as a creator)?

Daydreaming, reading (especially fiction), and daydreaming while I’m reading. Though perhaps not daydreaming but rather an action: writing by hand. Letting the tip of a fountain pen loose on paper—the right kind of paper; the miracle of tracing the trail of sleep on a page, which fascinates me every bit as much as a girl who is learning to write the word mother. There’s something about doing certain things with your hands that’s exciting and comforting in equal parts, simultaneously flight of fancy and nest. Writing by hand, trimming, embroidering.

8. Your idea of happiness?

To be where I am right now (night is falling, I’m writing, my dearest is nearby laughing at what he’s reading . . .). No invasive Wi-Fi, no internet, no telephone. The city is at my doorstep, I hear someone laugh, voices in the street; and the trees speak, too, their leaves trembling, stiffened by our Mexican non-winter, evergreen and brittle.

9. Your idea of misery?

This morning, reading the papers.

10. If not yourself, who would you be (of your characters)?

Maria, the dancer in La otra mano de Lepanto, or Clementine, the revolutionary seamstress in The Book of Anna. In real life I don’t find any pleasure in suffering, I’m not like Teresa de Ávila, who loved to suffer because she thought that pain was a path to God . . . that’s another story. The truth is that I wouldn’t want to be any of the characters I have written about and idealized . . . perhaps I would be Sofonisba Anguissola (the main character in The Virgin and the Violin), who was a painter in the Spanish court in the late 1500s and early 1600s, though the royal palace is not for me. Incidentally, the Prado Museum just finished (on February 2) a major exhibit of work by Sofonisba Anguissola (and Lavinia Fontana), finally giving my beloved Sofonisba the recognition she deserves in the city where she lived during the era of Antoon Van Dyck, Alonso Sánchez Cueto, and other contemporaries who admired her.

11. Where would you like to live (in one of your books)?

In the next book I’m planning to write. I can’t say what it’s about or where it takes place. I’ve learned to be incredibly superstitious, and if I say anything about this book (its characters, its setting), it might evaporate or escape—I might lose it. Is being superstitious a defect in an author? I can’t talk about the book I’m working on. Occasionally I have, and when I’ve opened my mouth I’ve lost a novel that I’ve spent time working on. In the early nineties I wrote one about Teobert Maler, a fascinating, extravagant Austrian who enlisted in the army of Maximilian the First of Mexico (the younger brother of Franz Joseph, the first emperor of Austria). Trained as an engineer, he became an archaeologist, financing expeditions to the Mayan ruins in the Yucatan out of his own pocket; others came along and pillaged them, and he tried to defend them in his broken Spanish in vain, hobbled by attacks of cholera and verbal assaults. He was the perfect character for me—I had more than a hundred pages written and edited—but the book just deflated when I began to talk to people about it. As a character he captivated me, and the themes of the novel did, too, especially its tragic and tender aspects, but then it became a stranger to me. And that’s not the only novel that’s fallen apart because I let it escape from my mouth. I learned the hard way never, ever to talk about the book I’m writing. Creation is a sacred, fragile thing. I know there are other writers who grow their texts by working verbally, or they “workshop” them, but that doesn’t work for me—I need silence and privacy to keep them from slipping through my fingers.

12. Your favorite color and flower?

Color: black. Although black is all colors and although there’s no such thing as “perfect” black, the no man’s land that it represents captivates me.

Flower: wild orchids, they’re one of a kind. And not necessarily the large ones.

13. Your favorite prose authors?

Today (I’m rereading her): Teresa de Ávila. The freshness and candidness of her prose, her directness and surgeon’s precision in looking at herself and addressing difficult topics that aren’t necessarily easy to write about, like her raptures, her extreme states of being, her “spiritual life,” all at a breakneck pace but without breathlessness, as if she were ambling along without letting her style falter, despite the fact that she’s writing passionately about impossible things.

Always: Reinaldo Arenas—El mundo alucinante (The Ill-Fated Peregrinations of Fray Servando). His prose is the opposite of Teresa de Ávila’s. It modulates to the frequency of what he’s writing about (as an author I’m more like him, my prose becomes saturated with the ambience of the world I’m creating, its place and the trials and tribulations of its characters and the spirit of the time).

Rosario Castellanos—Balún Canán (The Nine Guardians). The power of her childlike character, her examination of reigning injustice, her capacity to let us see all of a society without stopping to provide explanations. She’s a master, a genius.

Silvina Ocampo—her short stories. Silvina’s insane imagination, her sense of humor, her attraction to and resistance of violence, a sort of magnetic energy that dominates her stories, exploding unexpectedly, the delicacy of her brushstrokes and her bold confrontation of realities that can’t be addressed head-on. It’s a very strange combination: in her work the fantastic becomes humorous rather than otherworldly. And the humor isn’t always lighthearted, it can provoke discomfort that grows into hysteria, but it doesn’t quite get there; and it’s clear-sighted without giving over to desperation.

Juan José Arreola—his short stories. His plots are full of humor and irreverent intelligence, his precise way of building his tales, his fidelity to plotlines that would become absurd in another writer’s hands. There’s a reason why he was one of Borges’s favorite writers, and his favorite Mexican one.

Juan Rulfo—As a Mexican, that goes without saying. He wrote Pedro Páramo, the tale of a small-town tyrant, an abusive man. His son, one of many children begotten through violence, sets out to find him. He goes to Comala, Pedro Páramo’s hometown, which has turned into a literal ghost town—everyone in Comala is dead. It’s a story about post-revolutionary Mexico, and a ghost story, too.

Doña Bárbara de Rómulo Gallegos—I’m putting the protagonist (also the title) of the novel before the author’s name because she seems to be endowed with uncontainable energy, revealing the author (despite the fact that the author created her it seems that she, Doña Bárbara, created him, and that he gained renown far and wide thanks to her). And I’d like to add something that might sound cavalier: it was thanks to Doña Bárbara that he became the first legally elected leader of Venezuela. She’s not his only book, but she casts a shadow over the rest of his oeuvre.

José Eustasio Rivera—La Vorágine (The Vortex). The story of two lovers who elope to the jungle, the vortex of the title, to escape the obstacles to their union. In the jungle, where rubber is sourced, they discover a land that is not subject to human laws, written in prose that is appropriate to the turbulence of his tale. It’s a masterpiece.

José Lezama Lima—Paradiso. Lezama Lima wrote a poet’s novel, in which language is the protagonist. He pays homage to the classics, visiting Dantean hells, celebrating the delicacies of the kitchen and conversation and music, exploring the earthly world and the other world, too. It’s an extraordinary, elegant novel, perhaps more of a genre unto itself in which language is not beholden to reason but rather to dreams and verbal memory.

I know they’re all very different, I’m an omnivore.

14. Your favorite poets?

Today: Quevedo

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Gabriela Mistral

Delmira Agustini

Lope de Vega

Amado Nervo

I’m an omnivore when it comes to poetry, too.

15. Your favorite heroes in fiction?

Adrian Leverkühn (from Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus) is a work of genius, but calling him my favorite—hmm. That’s like calling Gregor Samsa or Pedro Páramo my favorite . . . I don’t know. I don’t have favorites.

16. Your favorite heroines in fiction?

Maybe Doña Bárbara of the eponymous novel by Rómulo Gallegos?

Maybe Duchess Sanseverina from Stendahl’s Charterhouse of Parma?

Maybe the Marquise de Merteuil from Dangerous Liaisons?

Maybe pathetic Macabéa from Clarice Lispector’s The Hour of the Star?

It’s the same problem; I don’t have favorites.

17. Your favorite artists?

Today: María Izquierdo, Louise Bourgeois, and Velázquez, specifically the works I suspect were captured on canvas by his wife, Juana Pacheco (who worked with him in his studio; she was the daughter of a famous artist and was a painter herself, but not a single work is attributed to her).

I love Turner and Bosch (they’re always with me) for very different reasons. Turner captures a fleeting moment when the gaze of the landscape and the gaze of the viewer mirror each other. Turner is able to capture the spark produced by contact between the human gaze and Nature in a way that makes them become one. Bosch, on the other hand, has a fractured gaze, representing demons, anxieties, jokes, moralities, and immoralities. He’s a storyteller just as much as an artist. I love him.

Other favorite artists are friends who have been with me for years, like the Mexicans Magali Lara, with whom I collaborated intensely during the eighties, and who I continue to work with to this day, and Marcos Límenes. Of the previous generation of Mexican artists (referred to collectively as “The Rupture”), Lilia Carrillo is my favorite (I didn’t know her personally but she inspired me to paint a portrait of the mother of the unnamed girl who is the protagonist of one of my novels, Before; I wanted to create an homage to her, to read the darkness in her final paintings). Or José Luis Cuevas’s nightmares; or the crazed canvases of Arnaldo Coen that rework the lances of Paolo Uccello.

And there’s another Mexican who stands out in my mind: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, who was also a painter, but whose works have all disappeared (most likely destroyed or attributed to others, like Juana Pacheco’s); not even one is known to have survived the ages. Cabrera, another colonial artist, copied her self-portrait (it’s the only painting we have that’s even close to her work, and in which we can see what she might have been like in life). I think Sor Juana might be my favorite of them all: I imagine her paintings were funny, sensual, and masterful, displaying intelligence, playing tricks, revealing secrets, combining traditions, just like she does in her “tocoquines,” poems she wrote in Nahuatl, and her “negrillos” adopting the way the Afro-Mexicans spoke, as well as the Andalusian-inflected modes of expression she learned at home.

And if you have any energy left, a few bonus questions, which we’ll call the Schnee Questionnaire:

1. How are your books born?

I picture their birth like this: While working on a text, as I’m taking a walk, looking for something, a rabid dog sneaks up silently and attacks me from behind, biting my heel. I try to kick it away but when I turn around it’s gone. I walk a little farther and out of nowhere it returns to attack again. I turn around and run. The birth of a book is like a hunt for something that has wounded me; I need to study it, understand it, hunt it down, and in the end it’s just my imagination being provoked by something outside of me.

Take my first novel, for example. I was twenty-five, and I was determined to write a gothic horror story set in Mexico City. A kind of urban Ann Radcliffe featuring a widower, his daughter, his wife’s ghost, and their fear of both it and other creatures from the other side. I went around collecting frightening urban sounds and scenarios that produced that feeling of terror of the unknown. I applied to the Centro Mexicano de Escritores, which was highly respected back then, for a grant; the year I was born, Juan Rulfo received a grant, and the year I received the grant, he was one of the tutors. I submitted five dozen pages of the novel I was writing (titled Dulces afectos), along with a proposal outlining the rest of the book. What I didn’t say (and that only I knew) is that, in addition to the elements of urban gothic, I was adding elements from things I loved, like my grandmother’s kitchen, the games I played with my friends, and more; I was trying to recover the things I had lost when my mother died. But in doing so, I destroyed my dearest memories, turning them into a nightmare.

Today I understand that I was trying to process the death of my mother and deal with my father’s immediate (and unfortunate) remarriage to a much younger woman who hated me and my brothers and sisters and wanted to eject us from the family home. There were six of us, the youngest was only two, it was rather dramatic. I embodied that horror in the novel in a way that made it even more compelling than it was in real life, even though that wasn’t the book I had set out to write.

2. How do you divide your time between your literary children (the projects that you’re working on)?

Badly. I love to work on one project at a time, just one, no distractions, obsessed night and day. I hate to be polygamous with my work. The problem is that they—my projects, as you call them—are not very loyal, sometimes they abandon me, so then I jump to another one. Eventually I return to the one I left because I had felt betrayed. The truth is that I can’t live without writing: if a “project” leaves me or even threatens to leave, I go after another one.

3. Do you have a favorite (literary) child?

Maybe the one I’m about to write, it fills me with desire. The book I’m in the process of writing is always my favorite of all the books I’ve written; either I’m still working on it or I’ve just finished it and it hasn’t been published yet. That connection between my hand and the text is incredibly precious to me. Once I publish the book it doesn’t feel like it’s mine anymore, I know it belongs to the readers, and the book and I become strangers. Books by my favorite authors are like open doors. But the ones I give birth to, the ones I create, they leave and turn their backs on me. Things like reviews, theses, and literary criticism of my oeuvre only deepen these betrayals by my literary offspring, confirming that they’re no longer my private secrets that I share with no one else.

4. What’s the best thing about writing in Spanish?

It’s the language of my childhood, my grandmother, and the authors I admire most in the world. For me Spanish is a passionate, carnal language, full of mixed emotions and scents; there’s not a single word that doesn’t have associations with flavors, odors, feelings, as if the words have lives of their own that they share with me. And the same is true for Spanish words I’ve heard or read for the very first time: they’re freighted, pre-inhabited. It’s possible one of my ancestors spoke another language, but I doubt it; the grammar and lexicon of Spanish touch me to the bone. And I’ve always known there are others; I’ve always had contact with people who speak other tongues. That wasn’t uncommon in Mexico; the people who worked in our homes came from monolingual backgrounds, so did the street vendors (who shouted “chichicuilotiiiitos” or “aquí el tlacuacheeee, rooopa vieeeja que veendaan”) and the women who sat at the entrance to the marketplace with their piles of mushrooms and wild herbs—they all spoke other languages. And then there was English: in songs, in films, it was the mother tongue of the nuns who taught us at school, it was everywhere, too. But none of these languages seemed as rich to me as Spanish. And they still don’t. And I say that after nearly twenty years of marriage to a North American who speaks only English.

5. And English?

It’s all wrong. When I write in English I walk among enemies. ![]()

Carmen Boullosa—a Cullman Center, a Guggenheim, a Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, and a Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes Fellow—was born in Mexico City in 1954. She’s a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, and artist, and has been a professor at New York University, Columbia University, City College, City University of New York, Georgetown, and other institutions. She’s now at Macaulay Honors College—City University of New York. The New York Public Library acquired her papers and artist books. More than a dozen books and over ninety dissertations have been written about her work.

Samantha Schnee is the founding editor of Words Without Borders, dedicated to publishing the world’s best literature translated into English. Her translation of Boullosa’s Texas: The Great Theft was longlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award and shortlisted for the PEN America Translation Prize. She won the Gulf Coast Prize in Translation for her work on Boullosa’s El complot de los Románticos.