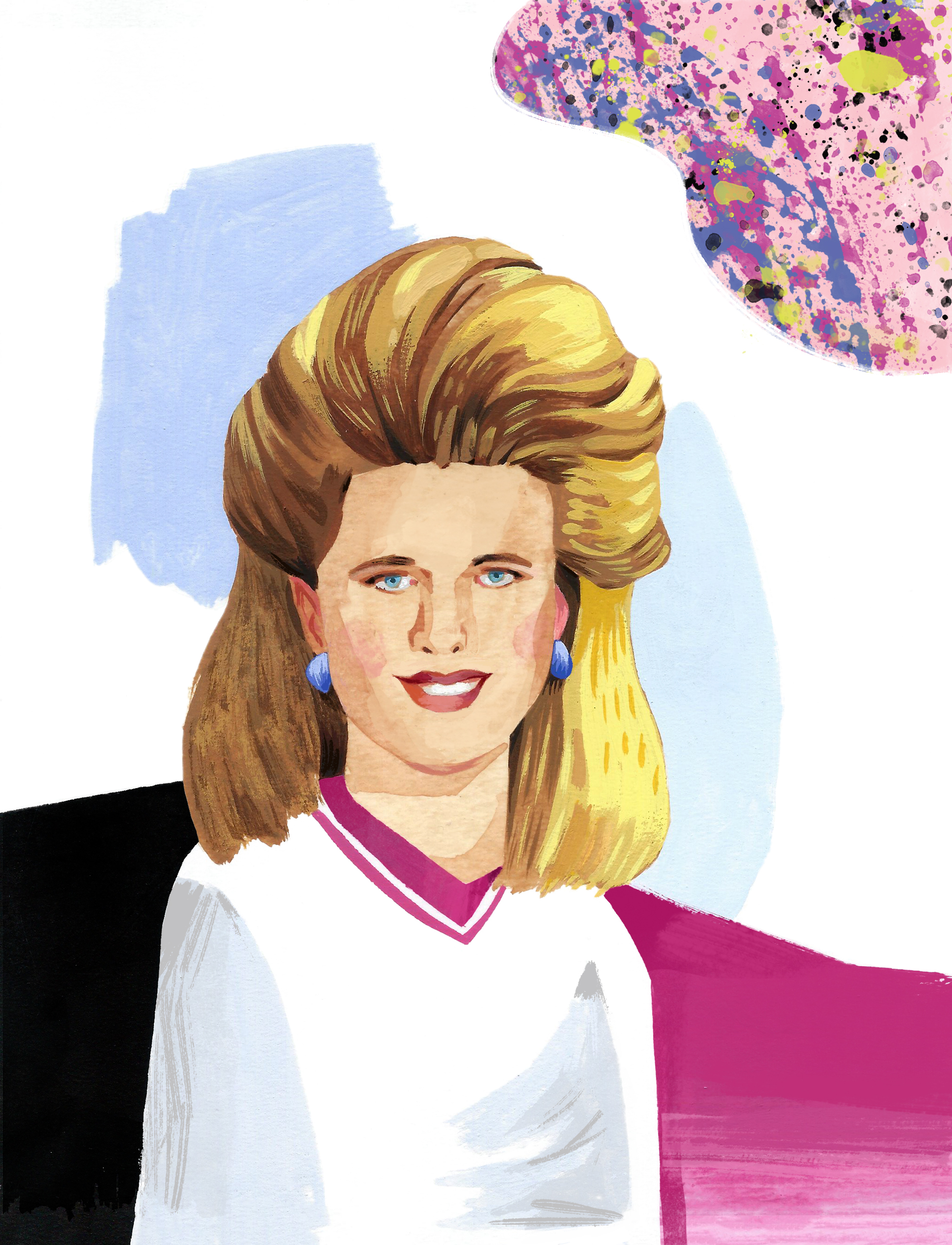

I have never felt more beautiful than I do now, sitting in this swivel chair, staring at my face in a movie star’s mirror, the kind framed with brightly lit bulbs. Behind me, the stylist teases out my blunt bob cut into a dandelion puff and encases my head in a cloud of hair spray that settles like sticky pollen on my skin. Next to me, my new stepmother undergoes her own beauty treatment: hot rollers, back comb, tease out, hair spray. Our faces are powdered, dabbed, brushed. We’re having a girls’ day out; today we are allies in the pursuit of beauty.

“See?” she says. “It’s fun to be pretty.”

The Glamour Shots stylist swipes my eyelashes with mascara, and like magic, my eyes seem suddenly larger. They’re blue like Dad’s, with flecks of gray and green. They glitter like tiny oceans, reflecting the mirror’s light. My blonde hair comes from Dad’s side too. Even Mom says I look like his sister, my aunt Mina, though she predicts that my hair will darken as I age. “No, it won’t!” I tell her, refusing to relinquish my golden hair. Already, I have learned the ways in which beauty and lightness are intertwined.

The stylist applies dabs of rouge to my cheeks, creating the illusion that I have just come in from the cold. The face in the mirror belongs to someone else now, someone more outgoing, less afraid of making a mistake, someone who thinks it’s fun to be pretty. She bats her long eyelashes back at me like a Disney princess.

Glamour Shots is inside the Park Meadows Mall, tucked between Claire’s and a pet shop where Mom thinks the animals are mistreated. Bubbly pop music floats through the air. Overhead, there is a TV where you can see your photos and pick out the ones you like in real time. The stylist shows me all the different shades of lipstick, arranged like flowers in a bouquet. I pick out a light pink. My stepmother chooses a deep red. Her thin hair is teased so high it looks like cotton candy.

“Look at us,” she says, squeezing my waist and pulling me to her. “Like mother and daughter.” I file this moment in the category of things I won’t ever tell Mom.

Our Glamour Shots package includes two outfits and two poses. For the first photo, I pick out a denim jacket and a floppy brimmed hat with a big sunflower pinned to the front. My attempt at a coy smile looks more like a gap-toothed grin, head tilted to one side, my hands popping out the collar of my jacket. With the Glamour Shots soft focus applied, my skin is smooth as plastic.

My stepmother and I pose together for the second shot. This one doesn’t involve outfits, but rather elastic tube tops that won’t be visible in the photo. We kneel and the stylist drapes a fluffy pink feather boa in front of us at chest level, creating the illusion that we are naked, floating in a luxurious pool of feathers. I don’t like the exposed feeling of wearing the tube top, of my bare shoulder pressed against her bare arm. She wraps her arm around my waist and squeezes. Her acrylic nails press into my skin. I am beginning to understand the way she moves through the world, touching hands, kissing cheeks, squeezing shoulders. I don’t like kissing her on the lips the way she insists we do, but I’m getting used to it. Her attention is like a warm spotlight shining on you. When it’s gone, you’re standing alone on a dark stage.

When I bring the photos home to Mom, she stares at them silently, as if willing the small squares to burst into flames.

“Do you like them?” I ask. We’re sitting at the kitchen table, which is scratched and stained from various craft projects gone wrong. She purses her lips, looking from the sunflower hat to the feather boa. I study her face, looking for clues. I’ve become attuned to her emotions, the way they vibrate beneath the surface of her skin like a taut string ready to snap. I look from the mole on her right cheek, to her dark eyes, to her nose, which she says looks like George Washington’s in profile. Her expression hardens, and for a moment I am afraid she will cry.

“You’re a beautiful girl,” she tells me. “The most beautiful in the whole world. You know that, right?”

“I guess,” I say, knowing already that there are different kinds of beauty, different tiers. Cinderella, for example, is beautiful when she’s scrubbing floors, but she’s even more beautiful when she’s wearing a ball gown. You can tell by the way people look at her.

“I like natural photos of you best, though. Where you look like yourself.” Her eyes search mine, as I search hers. Something has broken in them, some fresh disappointment.

“I know,” I say, wishing I had hidden the photos away in a drawer. Mom likes to says she is a natural woman. When she puts on make-up for work, she pokes around a bag of sample-sized tubes of rouge and cracked eye shadow palettes. She wears flowy skirts and silver jewelry. Mom thinks she spends too much time on her appearance, says she is vain. We avoid saying my stepmother’s name.

“I can’t help but think about JonBenét Ramsey when I look at you dressed up like this. It makes me sad. It’s not right for little girls to wear make-up. Little girls are supposed to play and not worry about how they look.”

I know JonBenét from her photos on the news. She’s a girl my age, with pale skin in a fluffy pink dress. A tiny princess with a tiara on her yellow ringlets. She’s dead now, murdered. In the photos they show, her skin is as smooth and airbrushed as mine is in the Glamour Shots. I wonder if Mom is telling me that beauty—the kind that involves hair spray and make-up—is dangerous, even lethal.

In a letter to Dr. Katz, our family’s court-appointed child psychologist, Mom will write, You should have seen the photos. They made her look like a teenager.

She doesn’t want to hurt my feelings, so she frames the photo of me in the sunflower hat and puts it on the mantle, but hides it behind my new second-grade school photo, which features my mismatched front teeth and crooked bangs. Sometimes, I’ll move my Glamour Shot to the front, only to discover days later that it’s been hidden again.

![]()

Make-up, lighting, hair spray, the perfect angle, a soft filter: these are the beauty secrets of Glamour Shots. A manipulated moment, captured on film. At Dad’s house, the photo of my stepmother and me is framed, placed on the antique vanity in my bedroom. You might mistake the blonde woman and the blonde child for mother and daughter, if you didn’t know better.

In this house, decorated with antiques and oil paintings, there are certain standards of being, of beauty. In this house, my bedroom walls are painted purple; the bedspread is a butter yellow. A slender silver crucifix hangs on the wall above a small wooden desk. My stepmother has arranged this room for the girl who lives here half the time, the girl in the Glamour Shots photo. This girl collects tiny porcelain boxes, reads Dear America diaries, watches her stepmother attentively as she curls her eyelashes, teases her hair.

“Lauren loves that I dress up,” my stepmother will tell Dr. Katz in their interview. “She wants her hair and nails done. Lauren wants to be like me.”

At Mom’s house, the standards are relaxed. The beds may not be made. There may be golden retriever hair on the carpet. My bedroom here is painted lime green, the bedside table bright pink. The color scheme is aggressively happy, upbeat, childlike. The girl who lives here wears overalls and baggy T-shirts, collects penguins, and reads every single book in the Little House on the Prairie series. On the doorframe of this bedroom hangs a mezuzah that the girl made in Hebrew school, the tiny prayer folded and tucked inside.

Over the years, each bedroom accumulates more stuff, the extra detritus of living two lives. The girl bifurcates, refracts, doubles back on herself. She is mutable, reflecting whatever world is around her.

In his final parenting report, Dr. Katz will write that one of the girl’s bedrooms is “too formally finished” and the other is “too unfinished.” He will say that the girl should be encouraged to define herself through what she puts in her rooms, what she hangs on the walls. I remember talking with Dr. Katz and showing him my bedrooms. I remember his thinning black hair and small, round spectacles, and how he nodded intently and asked me questions that I did not know how to answer. “The report is not intended to be read by the children,” Dr. Katz will write. But I will read it, years later when I am no longer a child. The sensation is like seeing oneself as a specimen through the eyes of a highly trained scientist. Like reading a fairy tale about one’s own life. In that report, I am Goldilocks, except everything is always too hot or too cold, too soft or too hard, too big or too small. Nothing is just right.

![]()

At Mom’s house, I play dress-up. Dress-up is not about looking beautiful, though it can be. It’s not about the doing but the being. I like to transform into someone other than myself. I do mundane things—dancing in front of the TV while my brother, Sam, is watching cartoons, playing with the dog, pouring myself a glass of apple juice—all while wearing too-big high heels and a sequined dress.

Dress-up always begins with the battered plastic tub with rope handles, the one we keep in the basement and that overflows with polyester, tulle, and sequins. A blue tutu edged in silver trim from my first and only ballet recital. A clown’s wig. A tattered sun hat. Mostly, the bin is filled with Mom’s old castaway clothes, which she says are hideous, and Can you believe I wore that?

To me, these items are magical, and so familiar that I could identify them by touch alone. A floaty pink chiffon bridesmaid dress from the early eighties with see-through sleeves and a rip in the armpit. A pilling polyester maxi dress with floral embroidery, once worn with wooden platform heels. A pair of scuffed red leather flats (which I will one day wear to high school when I finally grow into them). A sequined long-sleeved shirt whose matching skirt has been lost to time. A shiny blue sheath dress with puffy sleeves that Mom once wore to an office Christmas party.

These dresses intrigue me; they are secret clues to Mom’s past, the person she was before I existed. I wonder why she bought these clothes, which are bolder and more feminine than anything in her closet now. I imagine her wearing the pink chiffon dress as she applies lipstick in the bathroom mirror, holds a glass of wine, dances in a crowd of people. From old photos, I know her hair was once long, cascading down her shoulders in thick, dark waves. Now it is cropped short. Did she feel beautiful in these clothes? Did she feel like herself?

![]()

“Well, it’s all downhill from here,” my stepmother declares, walking through the door from the garage. I am flying down the slippery carpet stairs in my sock feet.

“Downhill to where?” I ask. I give her a dry kiss. Her leather coat smells like perfume, hair spray, and winter air. She sits on a step to take off her high-heeled boots. I notice they’re almost exactly like Jill Mordini’s, whose husband drives a brand-new Hummer and coaches Sam’s football team. Sam, at nine years old, is the star running back of the Titans. He pukes before every game, a symptom of anxiety that will persist until his freshman year of high school when he finally quits.

“Downhill to old age,” she says with mock self-deprecation. We both know that she knows she’s still pretty. “First, these lovely crow’s feet show up around my eyes. And now, the guy at the Lancôme counter tells me my skin is dry and aging. So, of course, I had to spend a fortune on these.” She holds up a bag filled with tiny jars and vials.

“You’re not old,” I say. “You don’t look a day over thirty.” She likes when I say this, even though we both know it’s not true. I’ve noticed how her eyelids look thin and crinkly when she puts on eye shadow.

“Thanks, pumpkin.” I turn to run upstairs, back to my room, but she stops me. “Come here for a second.”

I approach, close enough to smell the black coffee she drank and the Listerine strip she ate to cover it up. She’s studying my face with a look of concern.

“What is it?” I ask.

“We need to do something about this unibrow,” she says, touching the space between my eyebrows with an acrylic fingernail.

I reach up to touch my face. Horrified, I feel soft little hairs growing there.

“I’ll take you to get it waxed this weekend,” she says. “Before it gets any worse.”

I scramble up the steps and run to the bathroom mirror. She’s right. Delicate sprigs of dark hairs arch toward one another. I picture them marching steadily together, forming a hairy caterpillar above my eyes. I hate her for pointing out another defect, like the patch of dry skin in the hollow of my neck, or the little bumps on my upper arms. Once I see these parts of me, I can’t unsee them.

In his bedroom Sam is pacing back and forth, trying to crack his neck. I watch him as he walks around his room, stepping around his open backpack, his piles of clothes and books. He juts his head in and out like a chicken. He started doing this a few weeks ago and hasn’t stopped.

“Why do you keep doing that? You’re going to hurt yourself,” I say, leaning against his doorframe. His room here is decorated in a nautical theme, with a red-and-blue quilt, wooden sailboats hung on the walls. Though I would never ask her, I wonder why our stepmother settled on this decorating scheme, since Sam has never been sailing, and we live in a landlocked state.

“No, I’m not,” Sam replies, still moving his neck. “It feels good.” He stops suddenly, looks at me. “Did you hear that? Did you hear it pop?” I roll my eyes.

“You look like an ostrich,” I say. I feel annoyed with him, knowing that he’ll never have to wax his eyebrows or shave his legs, or worry that his bra strap is showing.

When Dad comes home, I tell him I’m getting my unibrow waxed.

“What are you talking about? You don’t have a unibrow,” he says, examining my forehead under the hanging light in the kitchen. He grips my chin in one hand and rotates my face from side to side. Above us, the bird clock chirps Carolina wren: seven o’clock.

“Yes, I do. See?” I point to the dark hairs that I will never not see. I need them gone. He looks over at my stepmother. Her hands are in mitts and she’s removing a Costco lasagna from the oven.

“You know she’s genetically predisposed,” she says, shutting the oven with her hip. “She’ll have to start at some point.” Dad pretends not to know what—or who—she’s talking about, but I know he just doesn’t want to get her started. If we both avoid mentioning Mom, then maybe she’ll forget that my mother and all my dark-haired relatives exist.

Years earlier, Dr. Katz had noticed the way my father deferred to his new wife, how he “gave up what appeared to be very good parenting instincts” in her presence. He called this dynamic “a ticking time bomb.” He predicted that unless something changed, “the children” would be “placed in compromising positions.”

“But she’s only twelve,” Dad says. He loosens his tie as if undoing a noose. His defenses are weakening by the second, and my stepmother and I know it. She removes the lasagna’s foil top, puts it back in the oven, and sets the timer for ten more minutes. Then she calls up the stairs for Sam to set the table.

“Please, Dad? It’s not that big a deal,” I say, even though it’s actually a huge deal. I can’t bear the thought of keeping my unibrow for another day.

“If you say so, Dolly. I’m jealous of anyone that can grow hair,” he says, reciting his favorite baldheaded dad joke. He ruffles a hand on my head.

![]()

I’m not sure when it happened, exactly. All I know is that one day I woke up and my stepmother had filled the refrigerator with single-serving containers of low-fat, sugar-free yogurt. They are like little plastic soldiers, stacked six deep and three high, their blue lids glinting in the refrigerator’s bright beacon of light. They come in a rainbow of flavors: vanilla bean, key lime, mango, banana cream pie.

Once upon a time, the pantry overflowed with peanut butter crackers, Chicken Biskits, Cheez Whiz, Fig Newtons, packages of ramen, and boxes of After Eights. Now there are no snacks, only the essentials: cans of tuna and tomato sauce, jars of olives and sugar-free jelly, boxes of angel hair pasta, bags of croutons and seasoned salad toppings. No more home-baked banana bread. No more Drumsticks and ice cream sandwiches in the deep freezer, only giant bags of frozen salmon filets and family-sized frozen lasagnas.

I am so hungry. Sometimes, when I’m alone in the house, I stand in front of the refrigerator door. Open. Close. Open. Close. I’m looking for something that I already know isn’t there.

On weekends, the bird clock taunts me, counting down the hours between meals. In the in-between times, I roam the house, looking for things I want to eat. I can’t stomach another yogurt, and tuna makes my stomach turn. At least there are clementine oranges. I eat them five or six at a time. I down sugar-free Crystal Light lemonade made from packets I find in the cupboard. The only marginally interesting food in this house is a giant bucket of Red Vines—her favorite candy—which sits on top of the fridge. I eat two, maybe three at a time, convincing myself that I’m satisfied. But I’m not convinced. Nothing here satisfies me.

Sam tells me he can’t stand it here. Most of the time, he’s grounded. He forgets to take out the trash, refuses to clean up his room. He can’t play video or computer games, can’t leave the house to see friends. The TV is in a locked cabinet, and only my stepmother has the key. He spends his summer afternoons riding his unicycle up and down the street, plucking hard green apples from the neighbor’s tree, and eating them with a pocketknife.

“Can you please not ride with the knife?” I ask him. “If you fall, you’ll stab yourself.”

“Who cares,” he says, riding past me.

I know how you feel, I want to say, but I don’t say anything. It is easier to believe that I can fix things myself, that I can fix myself.

What I don’t understand is how she is satisfied, how she is ever not hungry.

My stepmother has changed as drastically as our refrigerator and pantry. A few years ago, she started her own garden and landscaping business. Most days, she wears khaki shorts and a T-shirt with her company logo on it, pulls her thin hair back into a ponytail that she threads through a ball cap. She doesn’t bother with acrylic nails now that her hands are calloused from manual labor. She’s always been thin, but now she’s whittled down. Her arms are sinewy and tanned to a burnt umber. When she’s not working, she’s outside in a bikini top transplanting, deadheading, trimming, watering, mowing, transforming our suburban yard into a series of lush gardens that need constant maintenance.

In the summers, I work with her part-time along with a few stay-at-home moms whose sons once played football with Sam. We weed, water, plant petunias, haul sacks of soil. She pays us ten dollars an hour in cash, more than what I make at Panera Bread.

At first her clients were regular rich people, the ones with the nicer, newer houses in our neighborhood. But now she’s moved up and out of Cherry Creek Vista North and into the estates of Denver’s wealthy and well connected. She tells me her clients prefer having a crew of cute white ladies working their lawns over Mexicans who don’t speak English. Among them are a venture capitalist with an antique car collection and the owner of the largest chain of sporting goods stores in Colorado. Their houses have fountains, pools, horse stables, koi ponds. She knows all the gate codes. I’ve never seen the owners of these mansions, though I have the eerie feeling that they’ve seen me on their security monitors.

Workdays start early with a light breakfast. For her, that means a low-fat yogurt and black coffee. For me, that means two pieces of thin-sliced toast with sugar-free jelly. Around noon, we pause to eat lunch in the car, before heading to the next job site. She opens a single-serving container of low-fat yogurt. Drinks more coffee from her thermos. Says she can’t eat when it’s hot. I could eat an entire pizza. A whole chocolate cake, like the one the fat kid in Matilda was forced to eat. We’ve been moving nonstop since seven in the morning, but I pretend that I’m satisfied with the peanut butter and jelly sandwich and baby carrots I packed. I want it to be enough, but it is never enough. By the end of the day, I am lightheaded, sunburnt, hollowed out.

Dinner is the only time she allows herself to really eat, though she makes a performance out of consumption, bragging about how many bags of mulch she lifted that day, how many shrubs she planted. I understand that the harder she works, the more permission she has to eat. I start to see food in this way too. What has my body done today to do deserve these calories? For dinner, she makes rich food: creamy pastas, meat loaf, salads slathered with Thousand Island dressing. This feels, somehow, perverse. She and Dad drink cheap red wine or vodka with lite cranberry juice. If Sam is grounded, sometimes she won’t let him eat with us, making him cook his own boxed macaroni.

She is shrinking, and I am expanding. “All my pants are too big,” she says in mock sadness. “I’m as flat-chested as a twelve-year-old boy,” she complains, clutching at her chest.

Meanwhile, my jeans are tightening. My limbs, which have always been knobby and too long for my body, are filling out. Even my hair grows unruly. Every day, I blow-dry and straighten it to hide the curls that sprang up in middle school. As her body hardens, mine softens. When I look in the mirror, an unbearably round face stares back at me. Even when I pluck my eyebrows, apply eyeliner, mascara, blush, and concealer, I can’t see the face I once saw in the Glamour Shots mirror. Never have I felt uglier, and more desperate to be beautiful.

Movies and fairy tales have taught me that the young are more beautiful than the old, that stepdaughters should be more beautiful than their stepmothers. But next to her tanned and angular body, I feel pale, cartoonish, outsized.

When Mom tells me I am beautiful, I choose not to believe her. I fail to recognize her unconditional terms as a precious gift, shrugging them off like platitudes. Instead, I work hard to meet the conditions of my stepmother’s approval, her fickle love. The time bomb is ticking, nearly ready to blow.

Maybe if I lived here full-time, I could learn to like black coffee. I could stay outside in the sun and forget about food. I could whittle myself down into what I used to be—a child. But as soon as I get to Mom’s house, relief overwhelms me. There is food there, all our favorite snacks. I eat Oreos dunked in milk, mint chocolate chip ice cream, brown sugar Pop Tarts. But it is always too much. I can never find the balance between underfed and overstuffed. And no matter how much I eat, the hunger always returns.

![]()

Mom’s hair is its own character in our family drama. For as long as I can remember, she has complained about her unruly hair, its coarse texture, the way it defies gravity and anti-frizz sprays. Her ponytail is the circumference of a fist. She can go two weeks without washing her hair and you’d never know, the natural oils soaking back into her voluminous mane. She is forever growing her hair out, or lopping it off in frustration, agonizing over whether to color her roots or let them go gray, searching for the perfect stylist who can tame the untamable.

“I hate my hair. I wish I had hair like yours,” Mom tells me all the time. My hair may be easier to control, but I also dislike it in its natural state: curly, frizzy, unintentionally asymmetrical. Her whole life, Mom has searched for the secret thing that will make her hair good. Maybe this is why she indulges me in my own quest for perfect hair. Throughout high school, she takes me to nice stylists to get my hair cut, fills the space under the bathroom sink with hair creams and oils, diffusers and flat irons, pays for highlights when my blonde hair begins to darken, even caves when I beg to get my hair chemically straightened, a process that leaves it brittle and dull. If only . . . if only . . . we mutter in front of our mirrors.

When I learn how to French braid, Mom lets me practice on her. “Just get it off my neck,” she says, as if her hair is a tightening boa constrictor. She sits cross-legged on the floor in the living room, propped up against the couch. I sit behind her, dividing her dark hair into thick strands, weaving one strand into another, into another. In his report, Dr. Katz had written that I was most affected by my mother’s “paralysis,” that my “inhibited anxiety” mirrored her own.

But in this moment, there is no anxiety, no inhibition. We are mother and daughter, tribal animals, grooming one another, expressing love in the most primal of ways.

“Don’t be afraid to make it really tight,” she tells me, looking straight ahead. “I want this to last.”

“Beauty takes pain,” I say, cheerfully. This is my joke, what I tell my friends when we experiment with hair removers or pose for homecoming photos in uncomfortable high heels. We laugh because it’s the truth.

Mom lets out a groan as I pull back the hair behind her ears.

“Sorry,” I say, “too tight?”

“Nope, just keep going.”

When I finish the braid, I secure it with an elastic hair tie, step back to appraise my handiwork.

“It looks good!” I say. “Sleek, like a fish.” Mom pats her head gently. I hand her a mirror, so she can see the back.

“You really got it this time,” she says. “It feels good to have it up.”

“Mom, your head looks like a stegosaurus,” Sam says, walking by. We laugh. Her hair is so thick that the braid does form a stegosaurus-like ridge down the middle of her head. She leaves it anyway.

One day I, too, will get fed up with my hair, will get tired of its weight on my neck. At that point, I will be living in another state, no longer landlocked. I will go to the beauty school down the street where they charge fifteen dollars for a haircut, and tell the student stylist that I want her to shave my head. Are you sure? she’ll ask. When I assure her that I am, she’ll go looking for her instructor. I’ll wonder, How hard is it to shave a head? The instructor will come over with clippers. I will watch as clumps of hair fall to the ground, will feel the pleasant buzz of metal against my scalp. A couple other students will gather around the instructor, attentive to this impromptu lesson in how to uniformly shave a woman’s head. I feel as if some ritual shearing is taking place, as if the woman wielding clippers is a high priestess and I am her sacrificial lamb, as if this moment will divide my life into a before and an after. When she finishes, she will brush the loose hairs from my neck, unsnap the cape. Take a look, she’ll say. I will tilt my head from one side to the other, meeting my eyes in the mirror, inspecting the newly visible tops of my ears, the bare nape of my neck. I will see my face, and I will recognize the person looking back at me. ![]()

Lauren Rhoades is the director of the Eudora Welty House and Garden in Jackson, Mississippi, and an MFA student at the Mississippi University for Women. She is currently working on a collection of essays about family, identity, and religion.