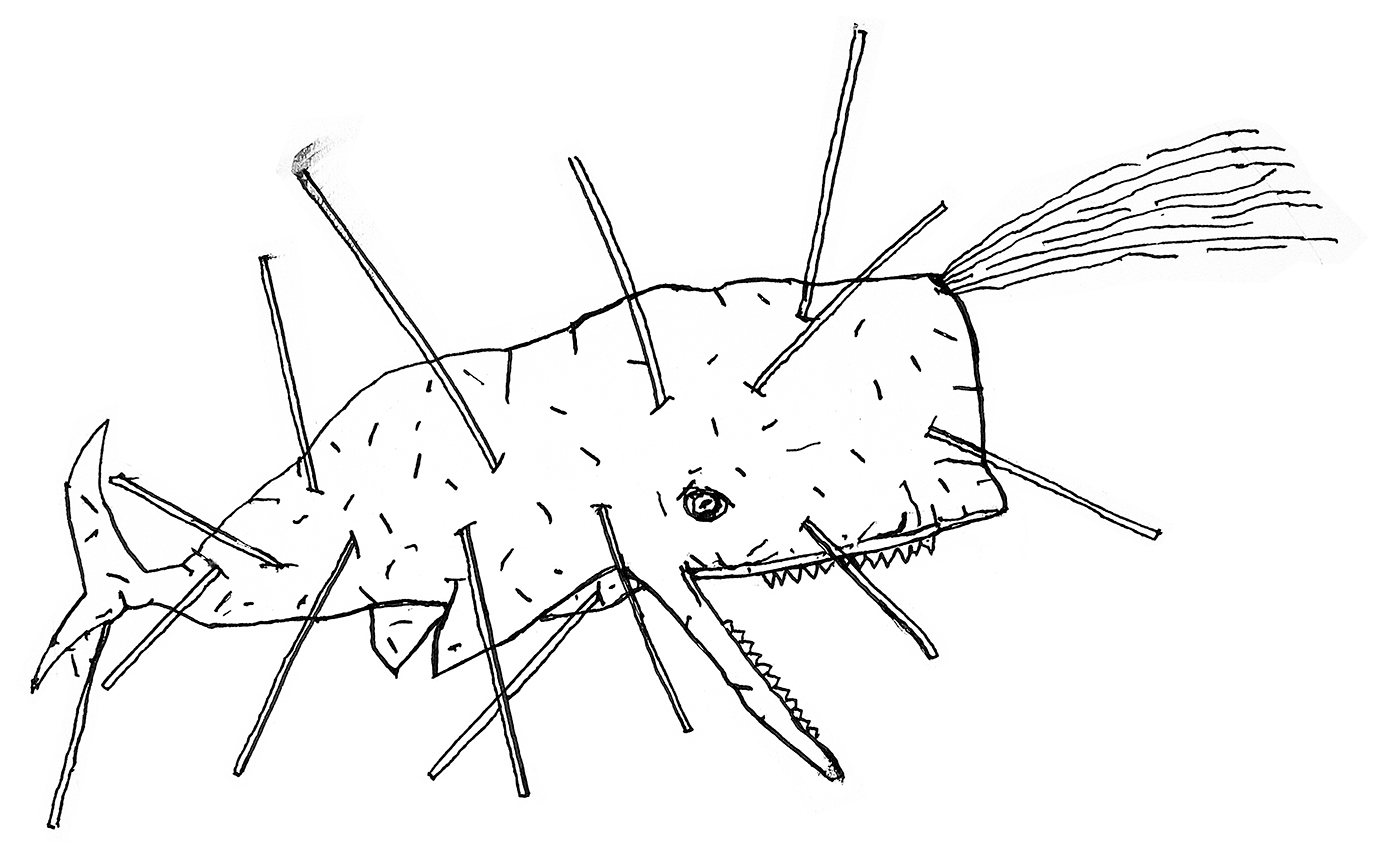

Side Four of Terry Allen’s new double album, Just Like Moby Dick, features no music. No track slices the vinyl. No groove spirals from outside to inside, to lock. Rather, in form with the rest of his career, a nearly six-decade stretch across more artistic media than should be fitted into a sentence (let alone a book, of which there are several), the plate contains only a visual companion: an etching of a sperm whale, its long body coated with scars and spiny with harpoon shafts. Though rendered in profile, fluke to jaw, the mammal is cocked toward the viewer, and casts a glaring eye our way. The whale’s mouth is wide open and teeth spike from its jaws, though the image seems to smirk more than threaten. And while the blowhole is spraying forth true to form—a sperm whale’s great nostril is in fact port side—the spew lines come across like a headlight beam cutting midnight. In fact, the general sense of forward motion serves to belie those old scars, making the leviathan a propulsive testimony to the past.

This is apt. Terry Allen’s volume of work has often been about reconfiguring and recomplicating history. About making new relationships with the old. In a sense, it’s as if he takes shards of what was, and composes new archives of what is. He assembles snippets of culture or family history, totem and ritualized tidbits, or the sea-like, savage landscape of his West Texas upbringing and post-atomic southwestern home. The resultant compositions unite fine-grit songwriters, NPR, the NEA or Guggenheim, or the juries of our most acronymic museums—MoMA, MOCA, LACMA, et al.—and all manner of sordid attraction along the highways between.

Highways being one unifying theme of Allen’s work and process. They are “a mainline,” as the album notes, “hard as a habit gone bad is to break.”

Just Like Moby Dick attends to this movement, to this communion with Allen’s vision of past-to-present, into perpetual. Everything here seems to be in transition. There are vampires and roadways, and relationships in fade; there are newly named disorders (“Abandonitis”), and dialogues with established masterworks (“Pirate Jenny”). Time, theme, and location are aswirl.

The album’s opening tune, “Houdini Didn’t Like the Spiritualists,” processes a real-life dilemma of the great escape artist: how to communicate with the afterlife. The song documents Houdini’s obsession with debunking mediums—his celebrity contemporaries—as an adjacent part of his quest to speak to his deceased mother, and later, to reach out to his wife from the grave. In the song, as in his life, Houdini finds that the clairvoyants and their lot were fakes. Even the man whose name evokes magical, near-otherworldly release cannot cross the unknowable divide. Still, he keeps trying. Keeps seeking something or someone real.

This is not the first time Allen has contemplated Houdini’s freaky quest. Writ large, Terry tends to process, review, and even redeploy his own artworks. He’ll fix on peculiar materials. Stuff worth prodding, over and under, again. Images or narratives, from baseball mitts to burning trailers to cinderblock, to bodies lacking parts, or which are made to lack parts. To saxophones and to fucking. His are the littered absurdities strewn across the southwestern landscape. The apex of this exercise, perhaps, was (or is?) his continued installments of Juarez. Released in 1975, Allen’s landmark debut album—or more appropriately, project—is ongoing, ever-evolving as addendum care of new, conceptual visual, text, audio, and hybridized form. Shards of its symbology spill across media, over years.

Other, kindred notions of movement on Moby Dick have to do with the lumbering demise of a relationship in “All That’s Left Is Fare-Thee-Well,” or the vehicle-as-life analogy of “Harmony Two,” in which a narrator states, “I’m passing you / gotta floorboard this car / and move on.” Swerving into the realm of the fantastic, by way of the droll and grotesque, “City of the Vampires” involves the coming together of two distinct, transitory elements: a traveling circus performs for the shape-shifting undead. In this case, versus spinning forward, the clock counts down to doom: “Ah you better go exercise the elephants . . . while you can.”

Allen’s songs, whether story or concept, as building mosaic or décollage stripped bare, even, are told from a range of points of view, though there aren’t many “we” numbers among them. In general, someone is usually up against something, be it the law, the landscape, stagnation, or tuck ’n’ roll vinyl. “They” either charge right at it, or “you” and “I” race away. An exception on Moby Dick is found in “Death of the Last Stripper,” a tune Allen co-wrote with Dave Alvin and Jo Harvey Allen, Terry’s wife. (Jo Harvey also wrote “Harmony Two,” and the noted actor-writer-director is both Terry’s lifelong collaborator and an artist of her own accord.) In the song, a group tries to cobble together a memorial for a dead woman, in an effort to find inherent value in her demise: “We’re the only ones in the world / Who even know she died.” They prep her for burial, and try to find her estranged son. In other words, they want her to have mattered.

While marked by that collective narration, “Death of the Last Stripper,” like “Houdini” and so many other Allen pieces, calls out to or complicates existing narratives of his work. In this case, the ballad both echoes the multiform (e.g., the Allens’ stage play and related album, Chippy: Diaries of a West Texas Hooker), and serves as a gentle twin to the vicious “Ain’t No Top 40 Song,” from the 1999 album Salivation. A stomper of a tune, “Top 40” is a tale of two unrepentant murderers, a his-and-hers exchange about committing the sin. Versus the “we” of “Last Stripper,” where the group mines the humanity of the deceased (“She had a boy / with some guy from Fresno), in “Top 40” “they” have little to say about the first victim. The news of her demise comes like a slap: “They found her dead / face down in a ditch.” From here, the suspects, the town, and their culture are scorched:

It’s blood on the car seats

Holes in the wall

Wild horse screamin’

Kickin’ slats from the stall

Headlights burnin’

Right out of his head

When the world’s on fire

And love is dead

The song takes straight aim at the in-vain lamentation of “Last Stripper,” in which the chorus of narrators “Got carnations at the Safeway / No roses there / Got no money for a preacher / So we tried to say a prayer.” And while the bodies in “Top 40” are throwaways, the stripper’s corpse, conversely, is elegized; her congregants even connect the woman’s passing to the economic death of the town, whose workers she would dance for before the mill shut down.

When I asked Terry Allen about this plurality of “we,” he proposed that “maybe the ‘we’ came out of the collaboration, but I really think it came out of the song. This thing that happened didn’t happen to one voice. I always thought of the ‘we’ as including the [stripper’s] kid,” a character who, now grown, has yet to be found.

At the close of “Last Stripper,” at least one of the folks who attended her still tries to telephone her child. This ongoing action speaks to another of Allen’s schema, in which a storyline, an image, or a phrase remains in process. A perhaps echo of Barthes’s take on jouissance, and the idea of a “writerly” text that allows the reader to interact by filling in blanks with their own narrative instinct, Allen’s open-endedness allows more investment from the listener.

Or, better put, Allen says you just gotta leave something out: “[A song] always feels better . . . feels right when it is mysterious and kind of open ended. You don’t mess with that. Because that’s telling you what the truth of a song really is, whether it’s something that you can verbalize, or just something you sense.”

Even the blood-bathed “Ain’t No Top 40 Song,” in which every detail is concrete, still delivers a cliff-hang, a loose end to gnaw. Both the male and female murderers insist that “if you knew” what their victims had done, you too would be glad they were dead.

Only, the murderers never reveal this vital secret, just as the stripper’s kid never picks up the phone. Whether violence or condolence, the story never ends.

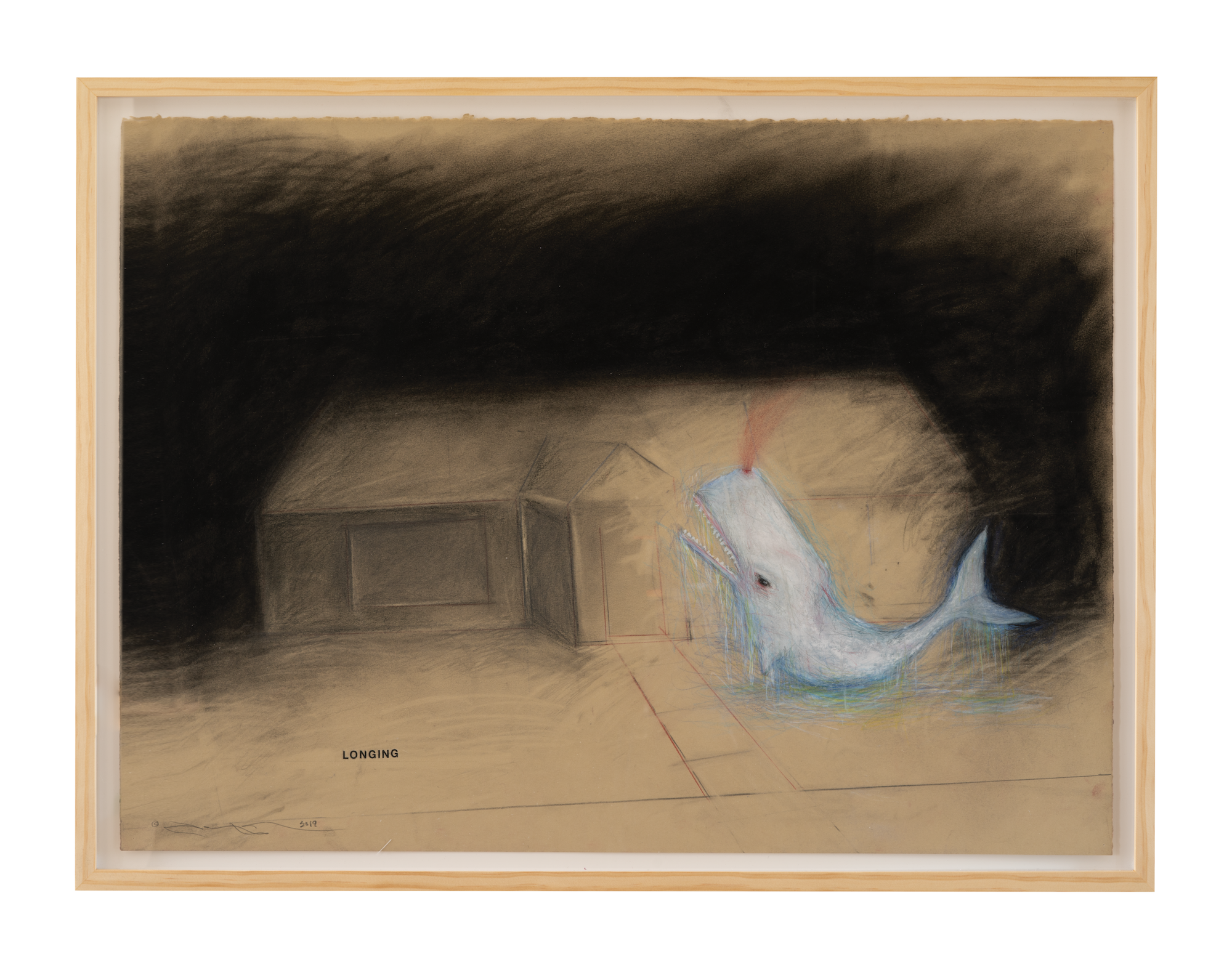

![]()

Obsessive, cultural echo telling, and/or big American tales in the mouths of everyday outcasts. Scars and headlights, etched beasts lumbering forward, with the ludicrous spears of history in their meat. A shipload of wordplay and wit to mark the wounds. Such are the measures across decades of Terry Allen albums, threading Juarez to its follow-up, 1978’s Lubbock (On Everything), to Just Like Moby Dick—and the ten or so in between. Beyond the recording studio, a trove of these references can be found in the conceptual assemblage Dugout, an “investigation as to how memory is created.” At once a re- and deconstruction of Allen’s West Texas lineage and his postwar boyhood, the work explores personal and group histories across canvas and paper, installed artwork, video and radio plays, recordings and written word. Baseball, jazz, sci-fi, aging, war . . . it took a full-length book just to unpack the artifacts (with Dugout being but one of his catalog-sized projects).

The wellspring of all this remembrance, Allen’s biography, has been best covered elsewhere. There is the pivotal impact of his parents and upbringing: his mother’s barrelhouse piano playing and his dad’s having transitioned from pro baseball to promoting concerts and sporting events in Lubbock. (Hey SMU, did you really toss Pauline Allen out for playing “devil music” blues with an interracial band? Or was she just gigged for the interracial band part?) There is the impact of West Texas, or the southwest itself, its vast span a palette, an unconquerable breadth. You can read of his early escape to Los Angeles and art school, of his now and again return to Lubbock as he made his name between these poles. Throughout the many competent biographies, you’ll note recurrent collaborators or confidantes—first and foremost, Jo Harvey.

Allen’s great explicator is none other than fabled provocateur and art critic Dave Hickey, and his musical compatriots include Guy Clark, Steve Earle, Lucinda Williams, David Byrne. The mainstays of his Panhandle Mystery Band—musicians of the first order—have helped to implement his vision for decades. “All of them are like family to me,” Terry notes throughout our conversation.

These known elements—the themes, the landscape, the collaborations—continue forth on Just Like Moby Dick. There are no fewer than five Allens on the record, meaning that the storylines and scraps of Terry’s past are now co-processed by his offspring. In a sense, they are now stewards of his personal history and narrative process. The collective is producing a family archive, in real time.

Yet there is a distinct, new texture to the whole of Moby Dick. Process-wise, this may have to do with the way the band was introduced to the material. Terry notes that, as opposed to his norm of bringing developed work tunes to the studio, “we played a lot of gigs beforehand, and played a lot of these songs.” Specifically, when Terry and Jo Harvey were gifted a block of boutique hotel rooms in Marfa, Texas, he decided to make hay by calling in bandmates, friends, and musical simpatici. “We wanted to do a songwriter thing,” he says, describing a rolling performance that included Joe Ely and Dave Alvin. These sessions, the live rehearsals that followed, and a consequent performance at Austin’s Paramount Theater, made Terry feel that even before one boot walked into the vocal booth, Just Like Moby Dick “had a life.” (A Paramount gig is also the focus of a 2019 documentary, Everything for All Reasons.)

Charlie Sexton’s production brings another new finish to the record. Though he and Allen have worked on a thick range of projects, what with Charlie being a fixture of the Panhandle Mystery Band (when not recording his own material, acting in feature films, producing records for the likes of Lucinda, or backing Dylan on stage), this is their first time as co-producers. “That was a whole kinda education for me,” Terry says. “Watching him work from a producer’s standpoint. We had these weird conversations, totally without saying a word. Just listening and gesturing. It was a funny communication.”

Allen and longtime producer/collaborator Lloyd Maines share their own well-worn, intuitive bandwidth. Allen notes that Maines, the pedal steel and production guru, and a partner to Terry’s process since way back in ’75, is “like my brother. We’re just jiving each other all the time.” (In duet with his chuckle, and for the third time in two minutes, Terry labels Lloyd and Charlie, and the lot of his band, “family.”)

To my tin-inclined ears, though the players and instruments are mainstays, the songs themselves sound more lush. The soundscape around the lyrics is less angular than some of its predecessors. More drifting, more wavelike, more . . . oceanic?

Yup. Oceanic. The record offers a bit more tidal current, a bit less steel on asphalt. This, again, is appropriate to its subjects: the forlorn Pirate Jenny, sailing “around and around the world,” or the blue canal of “Harmony Two.” The high plains chamber arrangement of bowed string and accordion feels appropriate for the duet about parting, “All That’s Left Is Fare-Thee-Well,” and suits the pronounced role of singer-songwriter Shannon MacNally, who even sings lead on “All These Blues Go Walkin’ By.”

![]()

By now it is clear that I am no journalist, critic, able reviewer, apt interpreter. I am no expert in music, art, aesthetics, or Terry Allen. I’m a middle-aged fiction writer who spent his boyhood in Texas, and who can eyeball from his desk the very same, Heidelberg Publishers edition of Jan Reid’s The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock that was brought to the house back in ’75. Point being, I have a lifelong, amateur interest in Texas music, and am an admirer of Terry’s work—more so every time I dig around. (Given the extent of his career, there is always more to dig.) I am among the many who are magnetized and motivated by his output, likewise his relationship to process. It astounds.

And, but, point being: when we spoke, I missed a gulf of a chance to ask Allen a series of on-point questions about this record. Instead, I fumbled through forty-two minutes of drifting statements about making, process, theme—some of which never even floated near inquiry.

Fortunately, I think, care of a too-constrained pair of lenses, one can consider the impulse and impact of two concrete elements from our discussion: a film, and a war.

The film, Captain from Castile, was presented to me as a sidebar of sorts, as a follow-up to my having asked Terry about his literary influences. (To be truthful: despite writing this feature for a literary/arts journal, I forgot to ask Terry to discuss his literary influences, and had to email him the following day.) Asking for a writer’s favorite books is a shitbag thing to do in person, and it’s a triple shitbag thing to ask over email. Bless him, though, Terry obliged me, despite his agreement that such listicles feel both “weird . . . and shaky pretentious.” He noted an early interest in the Beats, and in Paul and Jane Bowles; he listed Flannery and Faulkner, and Patti Smith’s “travelogue” books, alongside poetry by Ai and Sylvia Plath and Philip Levine and Susan Howe; and to cite the email itself:

pretty much everything by:

Roberto Bolaño

Sam Shepard

Denis Johnson

Add to this scrum the massive theater presence—Allen’s multiform series Ghost Ship Rodez: The Momo Chronicles is an extensive, interdisciplinary consideration of Antonin Artaud—along with Robbe-Grillet’s For a New Novel (which he read in the ’70s, along with Barthes). Out of an email reply, a literary tabernacle was framed.

But about that film. A follow-up email made note of two adventure novels from Terry’s boyhood: Sabatini’s Captain Blood, and Shellabarger’s Captain from Castile. He wrote that the books, and their adaptations (Errol Flynn in Blood, and Tyrone Power in Castile), “stayed with me. [They] pretty much saved my life . . . if not invented it.”

Pause on that “saved” and “invented” for a moment. I did, and then I streamed Captain from Castile (1947), an epic film set in sixteenth-century Spain, binding the Inquisition to imperialist might as it drilled down on a goodheart, the captain, who flees injustice by sailing halfway round the world, only to wind up in the company of Cortés. The Castilian is an adventurer caught in the twist of moral turbulence. Watching the film with Terry’s work in mind was like witnessing a lighter spark before taking flame.

My manifesto of Am Nots includes being any type of film reviewer. Thus, in associative words, terms, or phrases—and with a wink to Allen’s own use of narrative fragments—Captain from Castile features: adventure boy runaway-ism and masculine conquest; Inquisition Spain, year 1517; an escaped Aztec slave who is abetted by our hero; love across class lines; infanticide and matricide; a renouncing of God; an escape to the New World; the hubris and cunning of Cortés: his penetration and demolishment of the Aztec empire, AKA his bloody clamoring for anything to jack his name into history (plus gold, gold, gold); various body stabs and head wounds; the confident salacity of the Spanish-dancing Jean Peters; how her blouse drapes her body as she twirls for the legion; the high-bred captain himself, throttled by class, conquest, Christ (and Jean Peters); the 20,000 extras on set!; the epic shot of the horde marching across the lava plain in front of an active, smoking volcano cone; the film score: Oscar nod; the mutineers, traitors, thieves, and ships set aflame; the good captain’s ability to excel, to sell out, to come back from the dead; to redefine and remake himself . . . as civilizations are both eradicated and breech-born before his eyes.

All the while there is Cortés, Cortés, Cortés, whose exploits would bubble up in that masterwork, Juarez.

Unrest, violence, ridiculousness . . . war.

Alongside Allen’s channeling of the Castile figure and universe, the relentlessness of war was a second focal takeaway of our talk. The subject limns Allen’s “Warboy and the Blackboard Blues,” from that multi-year Dugout cycle, the project/series Youth in Asia (exhibited from 1982–92), and the “American Childhood Suite” from Just Like Moby Dick. The latter, a song cycle, connects three generations of the militarized, linking the elementary school lessons of “duck and cover” (“1. Civil Defense”) to the story of a female soldier headed to Iraq (“2. Bad Kiss”). The suite’s closing section, “3. Little Puppet Thing,” snarls at the dysfunction between citizen and state: “Make your body go here / Make your body go there . . . Make you do / What the good little puppets do.”

Allen’s family members had been in the navy or merchant marines during World War II, but Vietnam was the conflict that most affected him. “I was in LA all during the ’60s, and pretty much in total opposition to the war. But I don’t think it was a personal connection. It was . . . like this virus. It was everywhere, but it wasn’t in the house yet.” (Of note: our call took place while we were locked up in our respective houses, an unseen viral terror sheeting the world, no idea of when any COVID-19 curve might fall, let alone any highway open up.)

The analogy also serves as keystone to Allen’s insistence on mining the insidiousness of war culture, versus relying on the readymade, bow-wrapped, War Story itself.

His work on the ’80s documentary film Amerasia helped boost this critique. The film’s subject was a population of expat US soldiers living in Indonesia, and their supposed lifestyles of dope and savagery. Because of language barriers, Terry became a “weird translator between these American [Vietnam war] vets and this German film crew,” who believed that their subjects were “drug-smuggling scum,” and that the documentary was therefore a “kind of exposé.” Only, it turned out that the soldiers’ reasons for staying gone had nothing to do with drugs. They’d left the military, learned the local language, started families, and built relationships because they felt that America was simply too violent. “They were completely engaged in the society,” Terry says, but were afraid to bring their families back to the States.

He had lost a close friend from Lubbock to the war. After the Amerasia experience, however, “I started thinking about my cousin,” and how the decorated soldier’s having survived Vietnam “totally fucked his life up.”

Basically, the war killed him about twenty years later. It was just a long, bad ride for him all the way. But what it did to me [was make me] aware that war on that big scale . . . the cataclysm of the world, was happening internally to families and to people. And that really struck a nerve.

War, and the domestic culture that fuels it, remains present on Just Like Moby Dick. As we pivot from the topic, Terry echoes a line from “Bad Kiss,” itself a permutation of a line scattered through Dugout, and elsewhere in his catalog. No matter the conflict, the era, the condition: “Man, it’s just the same war.”

Oh, but there is humor in his apocalypse. There is farcicality and wisecracking and punster-ism and schtick, and it is awful form on my part to have waited this long to include it. Thing is, the bulk of Allen’s oeuvre deals wildness and wry ridicule in spades, as is fitted to example after example of wordplay. It’s ridiculous, his wit’s marriage to all this death, lust, and ritual.

Sidebar A: Terry’s the only person I’ve ever spoken with who knew about the US military’s attempt at making “bat bombs.” Yup, that’s right: a crew of World War II weapons geniuses thought it bright to strap white phosphorous grenades to the backs of Mexican free-tailed bats, with the goal of training the beasts to fly drone-like, and incinerate all of Japan. At the mention of the bat project, Terry filled the fable in on the spot, noting that during training out west, the creatures pretty much lit the wrong stuff on fire—barns, fuel tanks, an air base(!).

(I once brokered the subject to Barry Hannah, who dismissed me outright.)

Sidebar B: for the record, and harking back to Sexton’s production work on Moby Dick: that submersal, flowing feel can deceive the record’s dark hilarity. Case in point, the third verse of “City of the Vampires,” in which Terry’s description of the big top is accompanied by smart, carny-esque pomp music, mesmerizing and eerie, like somebody shoved a calliope in the mud, or smeared Fučík’s ubiquitous, tickling circus theme onto a dirge. After listening to “City” several times, lost in the concept, and the wailing of the “Vampiretta” section, I laughed out loud when I finally read the lyrics as standalones: “Baby vampire eyes shine at the show / No one thinks it’s alarming / Until they grab the clowns and bite holes in their / necks.”

Bat bombs!

Pedal Steal, Youth in Asia, Salivation (whose album cover features an image of Christ) . . . The riffing of words, the shift of meaning with a wink, or the redistribution of sign and symbol are everywhere. There is the tune “Peggy Legg,” about a one-legged dancer. Both the song title and story premise provoke an immediate response—be that to laugh, to cringe, or to twitch in-between. (Bonus wordplay: the song appears on the 1996 album Human Remains.) Only, like so much of Allen’s work, this ain’t no one-liner goof. The way Peggy Legg’s body graces the dance floor is lilting and empowered, if not agented fun. As the dancer herself says:

We all got missing parts

Right from the start

We got to live with

’Bout all a body can do

Is just stumble on through

What God gives to it

All you need is a heart

An’ just enough of a brain

To get your half-ass in

Out of the rain

“Abandonitis” is a perfect Allen title, and that Houdini tune sure is weird, and fun to sing: “Well he listened for his mother from the other / side of the grave.” Allen’s twang-and-cheek beckons a grin, even as it leaves us with the description of Houdini existentially bereft: his wife bends to listen for him, graveside, after Houdini himself has gone on. Guess what? It doesn’t work. Ba-dum-dum.

A triplet to this wordplay, and to the spare, poetic muscularity of most Allen lyrics, is the now and again blossom of filigree verse. The vampire town is a place where “There’s nary a soul to be found / When the sun glints off the church spires,” while the Cortés figure off of Juarez arrives in-country to slaughter Aztecs with “a Spanish Christ alive on his lip.” Such variations on language define his visual work as well, with phrases, fragments, and words repeated over and again, whether as accompaniment or within the composition itself.

![]()

There’s something about a constellation, or even an asterism, a half pattern, that feels applicable to my ever-building awareness of Allen’s work. It is a ripe time to refer to him as a “cult favorite” or “cult artist.” (Reading up, these seem to have been ripe terms to apply for many, many years.) But I think of him as a lodestar—one whose illuminance reflects the impact of the beacons around him, whether the artists, musicians, critics, or fans.

I first glimpsed Terry’s constellation at someone else’s live show. This was nearly twenty-five years back, a good twenty-five or more after Allen had put himself on the map. Having scored a two top by the soundboard at Nashville’s Bluebird Cafe, I took my steady dream date to hear Robert Earl Keen. Adding to the charm, I even convinced the board tech to make me a tape of the performance. Though the show was good and fiery, the tape didn’t do it much justice, and the dream girl soon quit me for some hack with a Telecaster (which is near-mandatory behavior in Nashville). The takeaway, then, was Keen’s cover of “Amarillo Highway,” which both he and the sound guy noted as a Terry Allen tune.

Soon after, the stars began to clutch. A music nut burned me a copy of Lubbock (On Everything)—kerpow! Just about any time I saw Guy Clark, Steve Earle, Lucinda Williams, or any other literary songwriter of record, Terry was name-dropped. And then, years later, in a printmaking studio at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, someone foisted upon me a copy of Dave Hickey’s critical bible, Air Guitar.

Hickey, an entity unto himself, beloved and/or reviled, a genius scourge (in every sense of those nouns), can also be considered about one chain link removed from Allen. The two Texans have collaborated, communed, and I’m guaranteeing conspired over the course of their decades-long relationship. Hickey wrote the majority of the text in the book Terry Allen (2010) and a cornerstone essay in Dugout (2005), has hosted Allen at major museum and gallery talks, and has profiled him for the Los Angeles Times and elsewhere, while contributing to catalogs, liner notes, exhibition copy, and what have you. Hickey has gotten more right about Terry Allen than I or anybody else likely will. (As evidence of their partnership: the full title of “Amarillo Highway” is “Amarillo Highway (for Dave Hickey).”)

Sidebar C: in an act of cowardice and self-preservation, I have held off now for several thousand words before confessing that if one wants to gain insight into Terry Allen’s gist, one should just read Dave Hickey.

“I talk to Dave usually about once a week,” Terry tells me, a hint of shit-talk clipped to his accent. “My wife and Dave are like, obscure third or fourth cousins, so, you know. I’m stuck with him as a kind of side-bet relative.”

The impact of Hickey’s critical insight aside—and that’s a sin of an aside to commit—his analysis of Terry’s artwork is fundamental to a larger understanding of Allen’s music, his process, and his past (as perpetual present). As Hickey notes somewhere, likely in my old copy of Dugout, Terry’s approach can be described as “Recursive Obsessive.”

See there? Dave Hickey needed only two words to gain purchase.

In addition to Dave Hickey one must asterisk Brendan Greaves*, co-founder of Terry’s current record label, Paradise of Bachelors. Greaves has considerable powers when it comes to written, recorded, and visual curation of Allen’s work. In addition to Just Like Moby Dick, PoB has re-released Juarez, Lubbock (On Everything), Pedal Steal + Four Corners, and limited series of archival recordings. Greaves’s liner notes have earned him a Grammy nomination, and his background in visual art and creative culture—not to mention his relationship with Terry—will be on full display care of his forthcoming book for Hachette, Truckload of Art: The Life and Work of Terry Allen.

For me, building on Hickey and the Bluebird and that burned Lubbock disc were the accumulative, even random blips of light in the constellation. There was the solo show at Austin’s Saxon Pub, maybe 2006, where I devastated Lone Stars while Terry delivered the room to rapture. There were the battery of references to Juarez, likewise the exhibits and installations, and the proliferation of recording credits by the comrades in Terry’s band: Lloyd Maines, Richard Bowden, Glenn Fukunaga, Davis McLarty, Charlie Sexton . . . They, he, seemed to be everywhere that mattered.

All these years later, and I still can’t hold back my gasp after that “Spanish Christ alive on his lip” line, or stave off the shivering joy that rolls over me with every listen to “Dogwood Tree.” As such, considering all of it, I am forever floored by a related question: How?

How in the hell can you make such music, and such art, for so long? How do you streak across discipline and medium, and cultural space, your light points linking Joe Ely to Artforum, your installations and stage plays and radio plays and line drawings and paintings like some larger orbital system, self-sustaining over the course of five decades . . . while still converting and convoluting with every scrap of new work?

Poor Terry. He didn’t ask for this kind of article, let alone this kind of positioning: as some polestar in the hemisphere of cultural production. (Poor you, reader and editor, as you didn’t ask for it either.) I was supposed to be talking to him about Just Like Moby Dick.

And yet, he navigated my spinout inquiries with compassion, and concision:

• On the nature of multidisciplinarity, and whether he had always planned to practice it: “You just go to the necessity of whatever you need to make something. And you use whatever’s available. And so I never thought of it in terms of being multidisciplinary or anything like that.”

• On Part Two of the same: whether or not he’d been influenced by multidisciplinary artists: “The people who influenced me were always the people who . . . You just wished you’d been that smart, or that you’d come [at a subject as they had]. People that moved you. You wanted to do something on your own that had that same strength.”

• On the MFA and/or art school practice of steering a “serious” artist toward a solitary discipline: “That’s academic protocol now. That’s just like ‘You stay in your slot, and I’ll stay in my slot, and hopefully [I’ll] get more money than you do.’ That’s not about making anything.”

• On the notion of high or low culture, and navigating the two: “I don’t even think that way, you know, about high-low culture. It’s like saying a ‘high-low person.’ What does that mean?”

• On raising a family while maintaining a creative career: “One thing we always did was, we took our kids pretty much everywhere we went. We also liked them, and so we’d rip ’em off! Jo Harvey’d sit outside and tape them, and then we’d use ’em in our pieces.” (He also reminds me that it wasn’t all highway, gig, and unbroken studio time. He spent several years teaching at Fresno State.)

There is no explicit “how” here. No blueprint of discipline, or concrete tactic in proficiency, let alone a surmisable, best guess as to how to sustain it. Rather, the “how” of it for Terry Allen is that you make what is right:

I think it comes down to what you sense is the truth or what you sense is a lie. I think those are the choices when it gets boiled down. And if the work is something that’s comin’ at you, I don’t care what kind of labels you want to put on it . . . If you believe it, if it strikes you as the truth, it’s the truth. You know?

And if it smells, it’s a lie.

Scar lines, headlights, hammer down, throttle. Motif and leitmotif, both operatic and drawled. Allen’s work is vicious and visionary, with a heaping side of jive. It is snakeskin flattened on asphalt (or was that a tire track pattern, or maybe just God?). It is a sperm whale with one eye cocked at you, coming on . . .

I hate to acknowledge it, but there is what can be read as a pronounced nod to mortality on Moby Dick. Mind it, there has ever been a shortage of death or decay, of specters or conjuring in Allen’s work. But this record might be taken to show a bit more of a tilt. All those mentions of transition, of transcendence? Of the inability to cross the void—and the relentless pursuit to make it happen? The image of Houdini’s wife at his graveside, listening, to no avail? Or how about the still-life descriptions in the song “All These Blues Go Walkin’ By,” be they the kimono on a hook, or “love letters hidden under the bed”? These items might be taken as an audit of the lived, versus the fresh sift of memory. And then there is Moby Dick’s closing song, “Sailin’ On Through,” with its naked anguish of “Every time the phone rings / seems some friend is gone,” and the Guy Clark-esque rouser of a chorus, which advises us to “break out the bottle . . . ’Cause nothing’s going to last.”

For Allen, death has forever been a punchline to seeking. Heck, sometimes while fate is screaming, he’s hawked a gob of spit in its maw. Does he still?

The final lyric of the album, the titular phrase, “Just like Moby Dick,” brings us full circle to that gallery of scars. To the headlight into darkness, and the flitting of American history in symbol. To the past we elude and the piano pedals we mash, until we just can’t out-stomp or outrun things anymore. Until we reckon with the end of the ride.

Or not. Now haven’t you been reading? Terry Allen’s process doesn’t follow a linear constraint. There are no grooves on Side Four that lead the needle into lock. No A to B, start to finish, The End.

“If you’re an artist, there are no rules. There’s only responsibility. But there are no rules.”

So those images of mortality? That seeming close of the story? You can bet your blubbered ass they’ll be folded into whatever’s next. ![]()

Odie Lindsey is the author of the novel Some Go Home and the story collection We Come to Our Senses, both from W.W. Norton. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in publications such as The Best American Short Stories, Guernica, Oxford American, The Iowa Review, and Electric Literature. Lindsey has received an NEA-funded fellowship for military veterans and a Tennessee Arts Commission fellowship, and is a writer-in-residence at Vanderbilt University’s Center for Medicine, Health, and Society. For more, please visit oalindsey.com.