Echoing, distorted drumming noise from way down in the hole, rhythmic pulses from fire hoses sloshing downslope, men shouted to each other over the noise of an enormous diesel generator and over the short grunts and extended revs of a four-axle truck crane, boom angled out over the stories-deep shaft, reeling something up. A big upside-down sedan from the 1960s trailing watery silt dangled, swaying over to the pile of tires and other debris that had been dumped in over the decades. Repositioning the grapple, the crane operator dragged the car right side up onto the prairie, a couple of sharp groans coming from the wreck. A crewman looked over his shoulder at old Boorham, the superintendent on this job. Who shouted, “Oh hell yeah. Bound to be the Brinks Robbery, Jimmy Hoffa.” Motioned prying open the trunk.

With a stink like something sold to gardeners, the contents of the trunk were hard to decipher at first, jostled and covered as they were with the mud of flesh and clothing, but yeah, that had been a big guy, judging by that shoe. Boorham pulled out the satphone the company had issued him—didn’t store numbers or other avoidable vulnerabilities—began keying. Told the guys to put a tire on the trunk lid.

The phone made dramatic noises and haptic buzzes in his hand, white-on-red tornadoes on the ground take shelter now blinked one second off, one second on, began scrolling seventy miles either side of a line Salina-McPherson moving eastward 20 mph. He looked at the sky; yeah right. Spoke to his boss in Wichita.

Two strong huffs of wind, sky still looked okay. Hail hit him like hurled sacks of ice, made it hard to help up the crane operator, who’d been knocked sprawling off the bottom step as she climbed down; ice shattering on his hard hat, followed the rest running for the tunnel leading down to the mossy launch crew bunker. They stood, wet and beat-up, against the walls of the echoing corridor as the noon sky went dark. Strong gust, pause. Wind shuddered loudly across the entrance, drawing out a breeze from behind them.

“Anybody got a flashlight, my phone’s got no light,” Boorham asked, doing a head count; no reason anyone should. Two lights came on. “Okay, this could be a shitload worse. EF5, we just walk down the hall, head downstairs. Save your battery.”

Someone answered, “EF5, bruv, they’re running three-fifty mile an hour, mile fucking wide per each. Hunt in packs.”

“Hey, maybe it’s just paid downtime till we get new gear,” Boorham said. “Just wish to God.” Sudden vacuum hurt their ears, physically made the eight of them exhale. Wind blew out of the lightless corridor behind.

Someone else said, “Best case, we end up on cots in a lunchroom someplace.”

“Yeah. Hope they come out for us sooner rather than later,” said Boorham.

Noise suddenly abating, one after another of them trailed up to the entrance. Saw a vast white column as wide as it was high. At the base, a dark approaching avalanche of atomized prairie, the column merging at the indefinite top with the green-black overcast, where streamers of cloud were drawn to the thing, whipped into it. Descending gracefully in the intervening distance, a berserkly churning cloud briefly obscured the more distant monster before walls of horizontal rain abruptly blocked the entire spectacle and the crew retreated, hands over their ears, into their deafening cave.

![]()

In the yore that Boorham thought of as home, there remained people who hadn’t outlived it. Women, or girls, of great importance to him, the more important for their having never left his home, who’d never lived anywhere else, never become others.

All the usual after-school things with friends, girls’ varsity sports, and a two- or three-day-a-week job as gofer in an architect’s office kept Shelda out until evening daily, and she took as many overnights as could be gotten away with—nothing really wrong with home, she just didn’t like to be there. Started showing up at her aunt and uncle’s place, her mom’s kin, sometimes slept on the foldout. They were fond of the girl, the aunt’s namesake; those equable, dutiful people were glad to have her in the house, just a matter of keeping tabs on her and their adolescent son, Boorham.

Shelda’s mother’d had a wartime job with the Air Corps repainting standard instrument dials with glow-in-the-dark radium numerals, and bone cancer had gotten her a couple of years before. The mother’s people calmly accepted the girl among their own, as a matter of course passing along a formidable range of kitchen and garage skills. Proper fried chicken, proper carburetor rebuild.

Not unusual in Texas, they were descendants of Ozark aristocracy, inheritors of Scots-lrish virtue, resolute and loyal and proudly self-reliant. Through a pronounced cultural quirk of holding multiple mutually exclusive views, they were hospitable, insular, tolerant, and suspicious. Welcomed “progress,” kept the grievances of their grandparents alive. Weren’t out of place in insecurely cosmopolitan Texas in that they read about the world in two daily newspapers and the Saturday Evening Post, Life magazine, and National Geographic, while making their home in a very Southern city, in its bones chary of intrusion. Collected oddities were on every shelf and sideboard, a book of New Yorker cartoons on the coffee table in the living room.

Knowing better, Shelda’s people almost reluctantly reinforced her difficulty in reassessing a position once taken—“Don’t back down, Shel”—a real disability sometimes. The girl readily learned from mistakes, but it had to be her own call to make. Her mom’s kinfolk reinforced in her as well the immemorial pride of being proud, the mulish stubbornness Shelda’d received with her mother’s milk. Very bright, headstrong kid drove her dad and her young stepmother crazy; kind of a relief that she wasn’t around much.

Had she not been so recognizable on TV, her father wouldn’t have objected to her going to the desegregation sit-ins. The classier department stores had years ago replaced brown, “Colored Only” water fountains with standard ones, and attitudes weren’t so uniform or dogmatic anymore, though the old signs were still up on most of the walls they’d ever been on, brown or black porcelain fixtures still in place in their own cramped areas needing no printed signs. Signs labeled separate and unequal places, sometimes even what lines you could wait in at municipal, county, state buildings, officially enforced there and privately elsewhere. Shelda as a little white kid might wander to the back window of a bus to join little black kids looking at the street’s phenomenal rushing away, and have a colored lady gently direct her forward again. Those polite Negroes she marched with were unlikely to go running around setting fires like they did up in New York and out in Los Angeles, but Shelda was a favorite of the local news cameramen—mingled races and organized civil disobedience, a new form of teenage scandalous behavior, embarrassed her father and got her a reputation at high school. Rumors of other wild-child stuff were invented, and her friends began to keep a distance.

Boorham was a grade behind her, remained predictably steadfast, pretty much a big male version of her, maybe not quite as bright; stayed away from the picketing though, had teammates to deal with. Sociable kid with diminishing opportunities to socialize as the school year went on, Shelda had the idea to make a jewelry chain out of heavy copper wire—in the era, labor-intensive adornment made of humble materials was fashionable. It was Boorham’s idea to wrap the wire around a piece of rod to form a coil. She refined things by sawing off links rather than clipping with pliers, so leaving a tight joint. After it got to be a foot long, they worked at opposite ends of the chain, sitting hip to hip, first cousins unknowingly engaged as their ancient ancestors would approve. They handed off tools, scraped burrs, bent the links closed, rarely handled each other, aware that that’d be ungovernable once underway. Repeatedly at first made an irremediable glop out of hours of work, teaching each other to silver braze so precisely. It got steamy in the garage workshop over the course of a few winter evenings, enthralling, a robust mix of fumes and pheromones. Boorham, a very long time later, figured he’d imprinted on his cousin, like a hatchling imprints on an irreplaceable other—he liked women a lot, a fundamental and not entirely sexual thing. Despite and because of close proximity, and with intermittent parental interruptions, they eventually came up with over a yard of chain, a 170-odd stout little links, neatly joined into a loop that hung well past Shelda’s navel. Something to be proud of. Proper swain, Boorham relinquished his share in it.

Abruptly leaving toward the end of that school year, against intense objections of family she went with a group out of state to register voters. With good instincts for whom to stay away from, robbed but never otherwise molested, Shelda still did have a creditable résumé: concussion, sprains, third-degree abrasion from being “dispersed” tumbling up the asphalt on one occasion. Slight, fair, freckled child, the bruises were glorious. The counties were proud entities, a highly efficient stage of social organization, more chiefdom than state. They preferred not to ask the state for tear gas or a lot of troopers, relied for social order on simple tradition reinforced as needs be by indigenous assets like the Klan. Troopers came anyway, and it was the state that eventually turned her loose with a fine, into her folks’ custody. ldealistic, Shelda may have been the least so of the half-dozen mostly black, middle-class, underage volunteers she went there with. It’d been an opportunity to leave home for some unchildish reason, a matter of self-respect. The experience was deeply memorable, not transformative. Civil rights wasn’t her calling.

In what would’ve been her senior year, Shelda wrangled a spot in a program up in Kansas at a progressive little college, where her course of study involved a slew of disciplines: archaeology, sociology, history, geology, statistical analysis, and others. In that end of academia, the works, emphasis depending on the instructor. In a couple of classes with her, an achiever named Gail hoped to have some college credits when she graduated high school.

The spring semester was over and Gail was staying put, enrolled in summer classes. Shelda’s dad was leaving increasingly angry messages with the college, demanding she come home. Chum was at the basement window, there under the front steps, looking out at her—she put a finger to her lips and he made a similar gesture—Chum was quick. He lived in the basement apartment with his haggard wife and two infants, was supposed to collect the other tenants’ rent, had let Shelda slide for half a month now. She was hiding under there because a man in a suit and another one in a polo shirt were ringing the doorbell; she assumed they were there to take her back to Texas. Chum went out and dismissed them. Under the porch, she scrubbed her chain between her palms.

Gail said, “No phone listed in their name up in Russell, but they’ll be fine with it. Mow the place. Swim in the reservoir. Get your shit together.”

“Oh man, you came through!” said Shelda. “Already gave my sheets and stuff to Chum,” picking up an Army-Navy store canvas pack. “Outstanding! What’s the address?”

“No idea. Going with,” said Gail.

Their first ride got them halfway there in an hour and a half, let them out at the northbound gas station. Being choosy about their rides hadn’t been a problem; ninety-five pounds apiece, those kids got lots of offers. In a newish Chrysler Imperial, pressed shirts on hangers behind his left shoulder, Caesar haircut, maybe late thirties, a good bet for a ride—they took in the daddy-man car, the Franklin Junior High Lady Falcons sticker, trotted up to talk to him. After they spoke briefly, the driver heaved an apparently very heavy two-foot-long cylinder off the seat and onto the floorboard, leaned over, and pushed open the passenger door. Gail got in; Shelda, having hesitated until the other two turned to look at her, slowly climbed in the back.

![]()

Now and again Shelda had some version of the same dream. In a concrete maze of broad tunnels and house-sized rooms barely lit by occasional slits to the outside, a girl’s wildly echoed shouting, protesting something being done to her, became frantic. No direction to the unintelligible screaming, just everywhere. Sudden terror of the dark, of not knowing the way out. It was a barely embellished memory, in fact, of a nighttime experience in the abandoned shore batteries at Galveston.

Lying in the weeds near the tunnel entrance of an underground bunker, Gail dreamed of anthropology lab: a druid-age bog mummy with the usual garrote around his neck, raising one eyelid on a moist white eyeball. Grayscale dream, but a jewel-like amber, green, and blue iris slid across the partly open eye, pupil stopping to look at her. In the dream, she tried to shout; the effort and sound woke her. Sat up. Immediately regretted vocalizing into the moonless, nearly complete darkness.

Whispered, “We killed somebody?”

“You didn’t kill anybody,” Shelda hugged her, cupped the bruised back of Gail’s head, nuzzled her cheek.

“Should’ve just let him,” Gail said.

Shelda murmured, “Huh-uh! Baby, not in a million years, don’t you even.”

In a little, with a squeeze and a pat, both lay back down.

After some length of time, Gail said, “Bet that’s east.”

Waking, Shelda said, “Or . . . yeah, ain’t going to be a city. Rise and shine. Watch your step. Jesus I’m thirsty.”

Shelda pointed a flashlight down the giant well. Gail crawled alongside, took a quick look down, backed away. Many stories below, the surface of the water was unbroken. Nothing to be done about the short skid marks on the concrete beside her, but there were a lot of other forklift and heavy equipment tracks around.

![]() Closing the trunk, panting from exertion, one or the other of them said, “Okay, then we take the car most of the way out to the highway. Walk out and hitch. No. Shit that’s stupid. Car’s a cop magnet. This is horrible.”

Closing the trunk, panting from exertion, one or the other of them said, “Okay, then we take the car most of the way out to the highway. Walk out and hitch. No. Shit that’s stupid. Car’s a cop magnet. This is horrible.”

The other said, “People at the gas station saw us going up to him.”

Neither woman had bothered to say that they would be jailed for murder. Runaway chicks lured the respectable guy, it turned fatal, they freaked out and ran. Some such construct. His bereaved family. Nope.

“He doesn’t make his appointment or get home or whatever, the cops do 197. Serious, serious hairy eyeball.”

“Okay, we take the car up to US 40. Back roads. Not really that far north. Maybe. I think. Forty goes all the way to San Francisco.”

“Gail? The car. The trunk.”

“Look goddamn it I can’t stop shaking! I don’t know! Why’d he do that! Oh God. I smell his cologne on my hands!”

“Sorry, sorry,” said Shelda. Then, “I want to go on up to Russell.”

After a while one of them said, “Where do you hide a Continental on the prairie anyway?”

“Imperial,” the other said.

A couple of hours later, lucky enough to’ve encountered no one as they drove up the narrow hogback lane: “Pretty sure I know where we are. USGS map called it Rec Site Ruin, always wondered what the fuck’s that,” said Gail.

Scouting places that might possibly conceal an enormous car, they’d bounced down an overgrown, buckling, unmarked concrete boulevard wider than the two-lane they’d turned onto it from. First caught sight of a fallen-down truss-work structure that must’ve been a small Ferris wheel, then saw a number of solid ramps and towers rising out of a blotchy pond, saltwater grasses in patches at the margins. Seagulls in the middle of Kansas. A weasel sitting up on its haunches looking back at them. The durable ruin, constructed of big chunks of stone rubble and concrete, the lower parts fractured, pieces falling away from heavily corroded rebar, was as much damaged by decades of vandalism as by deterioration. Rec Site Ruin covered less than two acres, encircled by a wavy, collapsing wall that still had remnants of little train rails on it and a couple of sizable rock buildings built into it that extended outside, galvanized roofs partly intact. Stunted volunteer trees did badly in the salty soil, graffiti everywhere, rust everywhere.

“Roadside attraction? Out here.”

“The fuck road anyway,” Gail said, pointing. “That one has a door big enough.”

“I don’t really see how we can drive it over there,” answered Shelda after a minute.

“Building’s packed with junk anyway, take forever,” said Gail.

Shelda said, “Going to look around.”

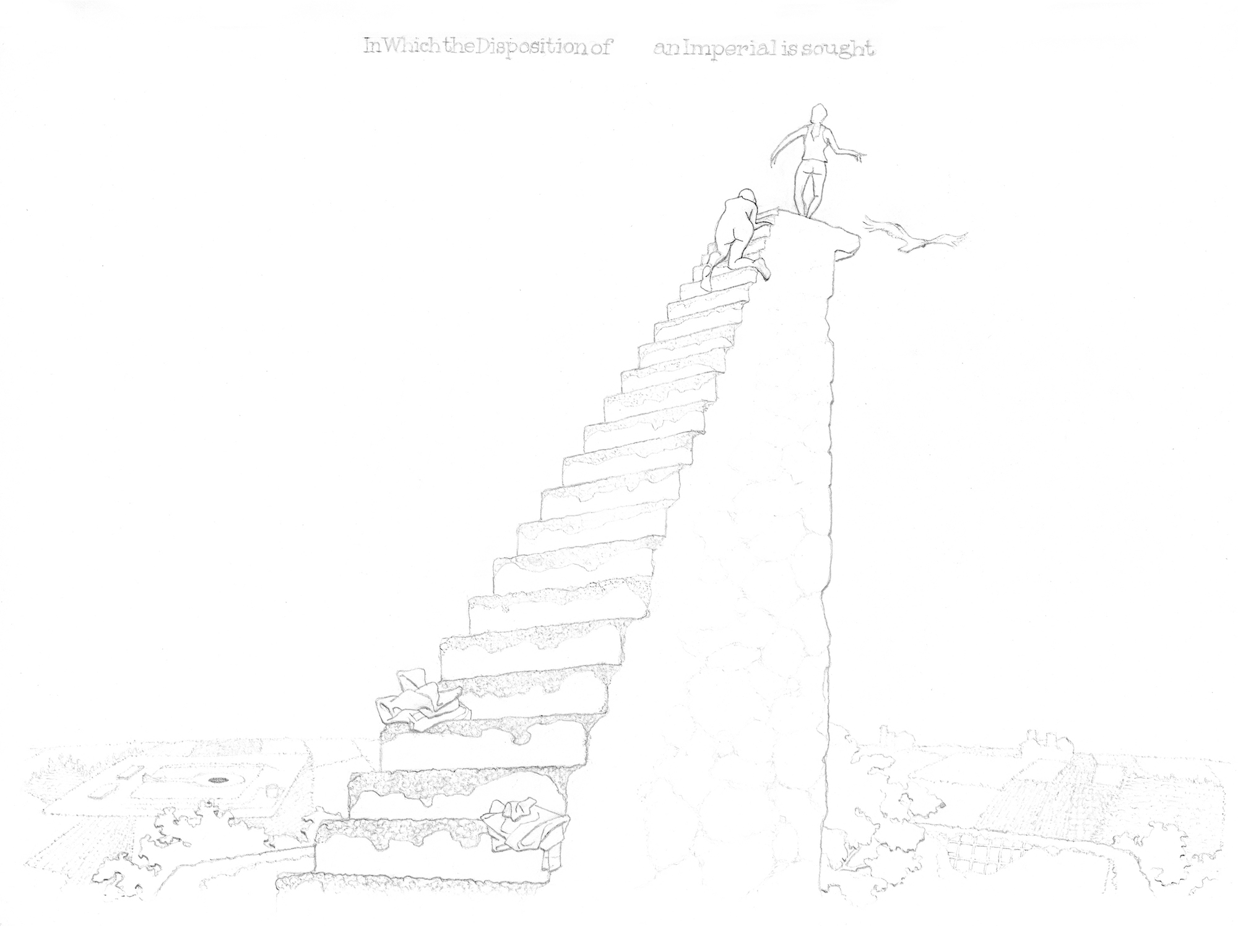

Wading through tall grass in thigh-deep water, Shelda lost a sneaker in the muck on the bottom. Pulled her tied-up shirt overhead, and making sure the car key was secure in the buttoned pocket, handed the shirt to Gail to hold along with their folded-up jeans. Shelda futilely tried to brush aside floating mats of yellow algae, bent into the water, leaned on Gail putting on the shoe. Led up thirty feet of steep, damaged rubble. Concrete steps, some steps entirely missing, the railings just rusted-out sockets or broken away. Gail was scared to death of heights, kept her eyes straight in front of her. Before the top of the suicidal high dive, she laid aside the armful of their clothes, went the rest of the way on all fours. Stood behind her friend, gripping Shelda’s upper arms, looking over Shelda’s shoulder. They turned around surveying, two small women wearing only farmer’s tans and tennis shoes on the massive plinth in the afternoon sun, trying to figure out what in the world to do next.

“That,” Gail said, pointing from over her friend’s shoulder at a big rectangle of concrete laid into the farmland, “Atlas silo.”

“What?”

“Missile installation,” said Gail.

Shelda said, “Okay. So?”

“Maybe there’s a storage building or something, those flat things sticking up,” Gail said, “subterranean garage or—hell I don’t know. Wishful thinking.”

Shelda said, “Gail wait a minute wait a minute—a guided missile base.”

“Took them all away a year ago. Finished up a year ago, I mean. They took away that kind of missile. Fences and all, looks like. It’s reverted back to the local school district or God knows, somebody like that, nobody. Derelict as shit.”

“Where’d you get all that?” asked Shelda.

“My mom’s a peacenik and Daddy works for Lockheed Martin,” said Gail, on knees and elbows, head down, hair hanging. “This isn’t getting any better.”

Shelda turned around, said, “What’s not getting better?”

“Don’t know how I’m going to get down,” said Gail.

At the end of the littered corridor, Shelda’s flashlight showed a safe-like door to either side and one in the end wall. “Three doors. Huh. Fairy tale, all the ingredients. Us, we’re a fairy-tale ingredient,” said Gail.

Standing open, lock mechanisms welded and nonfunctional, any door was heavier than the two of them could move. The flashlight showing them an empty passageway on one side, bottomless stairwell on the other, they squeezed past the middle door. Shone the dimming light around littered battleship linoleum, pale-green brut concrete walls. The tunnel had looked promising, maybe seven feet wide, but there was the claustrophobic likelihood of being unable to get out of the car. Already some graffiti around, including multiple palm-sized, black wreath–shaped stencils. They’d seen others of them at the water park.

Shelda tapped the flashlight against her palm, it obediently brightened a little, showed masonry nails driven into the walls. Three or four colors of yarn stretched among them formed a three-dimensional web in the air. The place was way too well visited anyway.

“Striking out,” Gail said. “Guess we could look at the silo thing.”

Cloudless, not quite sunset, no haze at all, buzzards far up there heading to roost. A shape-shifting black something of indeterminate size and distance tumbled across the sky, sometimes appearing symmetrical, other times not, a sheet of plastic maybe, alien spaceship, prankster hobgoblin. On hands and knees, looking over the rim of the fifty-foot-wide shaft, Shelda tried to see the bottom, lay down, face over the edge. Smelled kerosene. Water down there reflected the sky.

Giant lift machinery and stuff that Gail said would be there was gone; there were tunnel openings, and ladder rungs set into a channel. Graffiti around the rim and along the ladder: hearts with initials, school team names, and the wreaths, cave-painting instinct enabled by spray cans. Shelda zoned out a little, staring into the cavern—the thing was a monster, a straight concrete tube eighteen stories straight down, the water table finding its way in, pooled to an unknown depth. She sat up, looked around again. Blast doors had been retracted; no equipment remnants, nothing remained in place, just a great big hole in a circle of sawhorse-like, red-and-white-striped wooden traffic barricades.

From the low retaining walls on the upslope side, Gail said, “How’s it look?”

“Just. I don’t know, man. Messes your mind,” Shelda said after a pause.

“So yes?” said Gail.

No debris to jam the pedal with, no beer cans evident in the gloom. Gail hesitated, opened the trunk, looked away, got a tasseled loafer, slammed the lid. The Chrysler drove over the retaining wall, hit hard on the concrete, shooting sparks, wrecked its suspension, veered. The machine accelerated, dropped a front wheel over the edge, was guided around the rim of the pit, briefly stuck, laid a foot-long patch of rubber until a rear wheel went over and spun like mad. The big car hung there over the echoing column of air, roaring, just long enough for Gail to begin to turn a palm up, begin a shrug. Shelda had time to begin to wonder how to get at the bumper jack in the trunk. But a little torque did make it to the other back wheel, enough to stutter the car forward a few inches, just enough to lean heavily over into the abyss, roaring engine falling in pitch for its full count of three-second drop down the reverberating hole.

“Well that was . . . quick,” Shelda called over her shoulder.

![]()

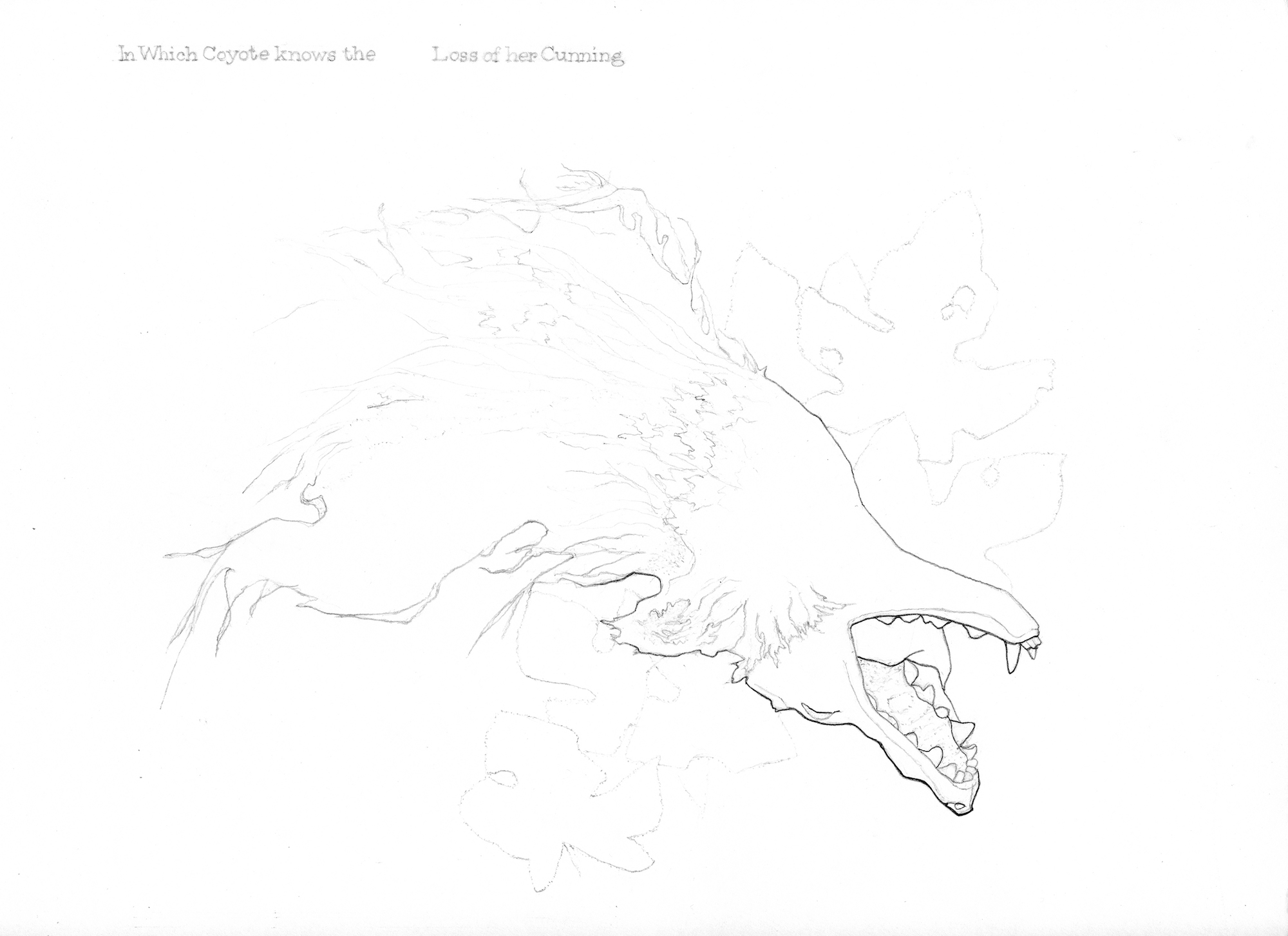

“It’s men, just axiom.” In the dorm room, Gail had uncapped another eight-ounce, taken a sip, passed it to her roommate, continued, “His brain stem’s jammed into his brain, pokin’ away. I mean how do you deal with that, the guy is trying to steer, leading him a chase. He’s a sweetie, gets along with just everybody, but he’s hanging on for dear life trying to steer. Chimps! They’re chimps. I mean you fuck him, you take care of his head, and, like, he’s—just assumes, well, of course, naturally. Like I owe him. Whole goddamn no goddamn fair!”

The roommate, two years older, said, “Gail, you’re sixteen.”

“So?”

“Un-grow up wouldja? Ook-ook. Mammals I swear to God,” said the roommate. She sat down facing Gail on the floor, passed the half-empty Boone’s Farm back to her.

“They could kill us,” Gail said. Suddenly standing, catching her balance. “Throwing up!”

![]()

The driver had exited the US highway onto a state two-lane, one of the diagonal roads.

“Whoa whoa where you going,” Gail said.

The driver said, “Russell’s forty-five minutes, get there by two at the latest. Want to show you something up here, you’ll love it.”

Several minutes later, Shelda said from the back seat, “Bob, get back on 197. That or stop and let us out. Now.”

“Hey hey, kay-passa baby, rules of the road,” the driver said, turning onto a yet smaller roadway marked by an enamel sign unreadable for all the bullet holes, keeping up a good rate of speed. Slowed beside a pretty creek.

“Look man,” said Gail, reaching for the door handle. Shelda let go of her back door handle. Had an odd little smile.

“Come on, you’re used to this. Gas, grass, or ass, no free ride,” smiled the driver congenially. Grabbed Gail away from the door, scrubbed her breast with a hand thicker than the breast. She pushed at his face trying to kiss her mouth,

“Get real, you asshole!” Then, “Get out of my clothes!”

He outweighed her by a hundred pounds. Pulled Gail against him, slapped hell out of the back of her head a few times. Gail became uncoordinated. Reaching for the shift lever with his left hand, the driver brushed at something on his cheek, inadvertently dropping it below his chin.

Shelda was seventeen. It was no trouble at all planting her feet behind the driver’s ears. At first clawing at the stout little chain, kicking, heaving his back against the seat, he had quit struggling in seconds. Thinking he was faking, would at any time turn on her, she eased up gradually. Rattling catlike noises lasted another few seconds. The car had drifted off the road. Gail, dazed, managed to stomp on the brake. She jammed the shifter into park, shook her head trying to make her eyesight stay still.

“Jesus Christ,” she said. “I . . . No way it’s that easy.”

![]()

The twelve-foot moldboard rotated out horizontally, waggled to and fro, lifted one side at a time as the massive front wheels tilted left and right. The blade pitched way down and back up, raised and lowered a couple of times, did all that in jerky hydraulic gyrations, came back to its original travel position. He cut the engine.

“We drank out of one of those tall hydrants, we going to die?”

Startled, he took his foot out of the opened windshield of the road grader, “Hi ma’am, didn’t see you. No you ought to be fine right along in here. Sure get your minerals.” Young guy in a green work uniform folded his copy of Mad around a sandwich, stuffed it with the rest of his lunch into a domed lunchbox. “You ladies way out here.”

“Yeah, bad boyfriend,” said Shelda. “Got pissy and kicked us out.”

“That was wrong,” he said, and seemed at a loss for words. Leaned way down, put out his hand, and introduced himself.

“Alice,” said Shelda—the Allis-Chalmers decal.

“Dorothy,” said Gail, “pleased to meet you.” Mad magazine, thought Gail, pretty racy for a Mennonite; said, “No, man, finish your lunch, it’s only us.”

“Oh no, thanks, I’m done,” he said. Looked at them expectantly. “Been walking long? You’re nowhere.”

Gail said, “Just this morning. Camped rough.”

Pointing at the machine, Shelda said, “Certifiably cool what you just did.”

He adopted a pose, finger in the air, “Every valley shall be filled and every mountain and hill shall be brought low and the crooked shall be made straight and the rough ways shall be made smooth.” His expression fell, “Wow, I . . . no. Real wrong to go and kid with that.” Resuming his good cheer, “I’m headed back in. Want a ride?”

Hanging in the doors on either side of the operator’s seat and its myriad hip-high levers, they shouted to be heard over the engine noise behind them. He was telling Moby Grape jokes, best they could tell. Waited for the longer pause and laughed.

Shelda pulled a souvenir ring with a heart-shaped pink coral off of her little finger, leaned in, said, “Trade ya,” indicating the lunch box.

“No ma’am, sorry, should have offered, you got to be hungry,” handing her the black wrinkle-finish box. It looked many years old. “Hope you don’t mind eating after me. Tea in the thermos.”

Accepting it, Shelda said, “I have to thank your wife for lunch. Please.”

The man said, over the engine, “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers for thereby some have entertained angels.”

Entirely unaccustomed to choking up, Shelda said stubbornly, “I pay my way. Got to be a verse.”

After a moment, the man held out his hand for the chintzy ring. Looked at it, read, “Galveston Island, Texas. Never been. Thank you ma’am. For sure she will love it.”

Gail, the vegetarian, got the half-banana and most of a wax-papered bundle of pretzels.

The road grader backing away from them, its moldboard performing the half-ton equivalent of a goodbye wave, Gail said to Shelda, “You should not have given him that ring.”

Shelda didn’t answer. A big front-end loader rolled past others parked in a neat row, dumped and tapped out the last of its four bucketfuls into a truck. No hurry. Everybody took a smoke.

“Hey guys,” said Gail. They all straightened up.

“Well hi,” said one.

Gail declined a cigarette. Shelda accepted one, said, “What-all you guys do out here—I’m taking mental notes.”

A short round man said, “Road sand, miss. Salt and ready to go.”

“So where’s it go from here?”

“Okay, this time of year they’re staging the dumps for winter. All over. County gets beaucoup for it, especially if we use our own trucks.”

Shelda said, “Y’all work in winter too?”

“Yes ma’am. Busy time.”

Shelda said, “Wow. I cannot imagine. You guys right here keep all the roads drivable.”

He said, “Well, best we can. Lots of them, yes we do. Look ma’am, what’s up?”

She got to the point. “Do you supply Russell?”

“Yes ma’am, Russell County.”

“Staging up there now?”

“Could, yes.”

“We’d like a ride.”

“Oh! I see. Little slow. Up to him, miss,” indicating the feet in the dump truck’s window, called, “Hey! Perry!”

Gail got out at US 40, went home to San Francisco.

![]()

Outside the bunker, he used the satphone to check the weather. Some more coming, looked like. A few hundred yards from where he’d parked it, old Boorham’s wadded-up Ram crew cab had no glass; bodywork missing or caved in, blasted thoroughly with wet sand, had rolled, bounced airborne, happened to come to rest on its wheels. Boorham instead walked over to the cleaned carcass of a vintage Chrysler hunkering on what was left of the prairie grass, its rear end crammed under the wheels-up potable water semitrailer.

Hood and trunk lid gone, and two out of four doors, what remained had been pretty well stripped to the bare metal. Hoped he’d get around to checking out an odd stainless steel cylinder on the floor where the seats used to be. Water still draining from around them, stirred and disassociated, the bones had been hosed down, but many were still in there, the deep trunk offering a container for them to be bounced around in. Tangled with some vertebrae was a slender, round-linked chain, long for a necklace. Boorham fished it out, scrubbed it between his palms. Tumbled to a coarse polish as had the human bones, it was copper, a hefty little thing.

Taking inventory with his rigger and with the crane operator, Boorham noticed first that the office and bunk trailers were simply gone. Then that the site had not after all taken a direct hit. The flatbed semitrailer had been flipped end for end into a drainage channel, upside down but intact, yellow tie-downs hanging off into the water, load of site-specific engineered steel forms no longer around. The crane truck did look promising. Though one side’s outrigger pads were skidded off of the concrete apron, the thing was upright.

The crane operator, left arm in a sling made of one of the guys’ shirts, climbed up for a look at her machine, kept shaking her head. Came back down, indicated a huge adjacent piece of wreckage with her boot, reported, “Bottom hydraulic pump and line got killed, no fluid, outboard control panel trashed. Truck might start, I don’t know. Sand in everything. There’s a manual cab-over, off chance there’s something to do under there. God knows if it’s got brakes. The orange peel is down slack where we can uncouple it, duh, but the goddamn boom pointed way around the side like that—shit. Surprised if the gearmotors work. Sand in everything and, like I say, no hydraulic. Tools and fluid were on the flatbed. Crane might start, winch might work, perfect fucking hog to haul around straight if they don’t. At a glance.”

Boorham said, “Mm.”

The rigger shrugged, “Possible ride.”

They skirted the hole, looking for something they could use, didn’t see much. Heard exploratory, preliminary cranking sounds from an engine behind them. Diesel tank on the ground, incidentally didn’t appear to be leaking, kept by a logjam of skeletal steel and a low retaining wall from rolling uphill to an unfulfilled fate. Batching plant knelt, with large pieces gone, its mangled hopper several yards away, wrapped onto the crane. The carcass of the massive diesel-electric plant remained on its I-beam footprint, stripped to the cast iron.

Boorham felt distracted. Despite her being in many ways Gail’s opposite—big, middle-aged, and politically to the right of libertarian—the crane jockey reminded him of Gail, her manner, expressions. He wasn’t in the habit of arguing against his crew’s loony conspiracies of multinationals and weird cabals, because they made as much sense as anything else, differed only in specifics from the nonsensical crap he and Gail had known to be true. Some of which nonsense had nevertheless proved out, continued to.

The last year or so, Boorham had done work for a company specializing in fortified dwellings, increasingly popular among those who could afford them. He was out here supervising the site prep and initial construction phase of someone’s country house in the missile silo. Figured he wouldn’t be returning to it after this setback, since the principal of the company, along with her caddy and a couple of others, had been successfully blown up. Boorham doubted, in fact, anybody would get paid.

When Gail crossed his mind, often Shelda would too. Some sense of duty, something absurd but ingrained and difficult to resist, a vestigial notion of rules to be followed, had prompted him to drop the necklace back into the Chrysler’s trunk among the bones. Calling himself an idiot, he turned away and went back for Shelda’s chain—that had to be her chain. Boorham broke into a shambling trot. ![]()

Tim Coursey has lived in Dallas, Texas, since late 1948. His day jobs have included foundry hand, furniture designer, and maker of fake antique Japanese sword fittings. For a slow reader, he reads a lot.