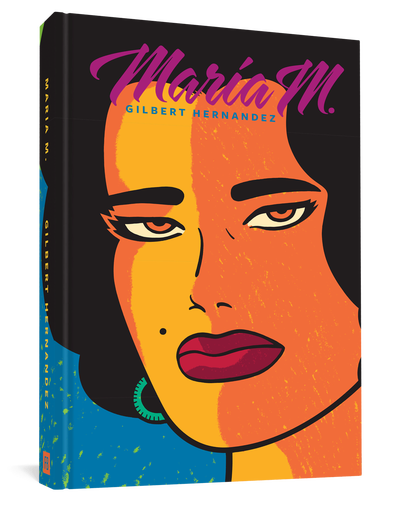

Maria M.: A Graphic Novel by Gilbert Hernandez

Reviews

by Robert Rea

The art of Gilbert Hernandez is so colossal that even now, thirty-plus years into his career, the vastness of its terrain is still being mapped out. A living legend in the world of comics, he invented a small town called Palomar, located somewhere south of the U.S. border. The entire series, which launched in 1981, forms a single, connected universe. Think Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, but with thought balloons. And now, with the release of Maria M., the saga continues in what just may be the most groundbreaking chapter yet.

Just as Faulkner does with Yoknapatawpha, Hernandez creates a vividly inhabited place grounded in the shared history of its denizens. The center of this universe is a skinny-legged, buxom beauty named Luba. The series jumps between different periods of her life, as she goes from new girl in town to aspiring entrepreneur to absent and abusive mother, finally ending up as mayor and beloved matriarch. Near the end of the original run—assembled in the 2003 trophy work, Palomar: The Heartbreak Soup Stories—you learn that Luba’s mother, Maria, abandoned her as a child. Maria M. circles back to that story, but with a high-concept twist.

The most recent spin-off—a four-volume stretch that also includes The Troublemakers, Chance in Hell, and Love from the Shadows—nudges the saga into a new phase. Billed as a collection of B-movies, they radically expand the Palomar mythos. Visually, Maria M. is pure cinematic spectacle, full of wide panoramas and dramatic close-ups, and a fitting homage to the larger-than-life images of the big screen. In the past Hernandez has used Hollywood to talk about the global reach of pop culture and how it takes root in Latin America. The fact that Luba owns a movie theater adds another layer of subtext to Maria M., and here’s the kicker—Luba’s younger sister, Fritz, stars as their mother. As unreliable as any biopic, it fails to hold up as Palomar history. Never mind. The cleverness of the conceit—aside from the next-level world building—is that it subverts the same genre it traffics in.

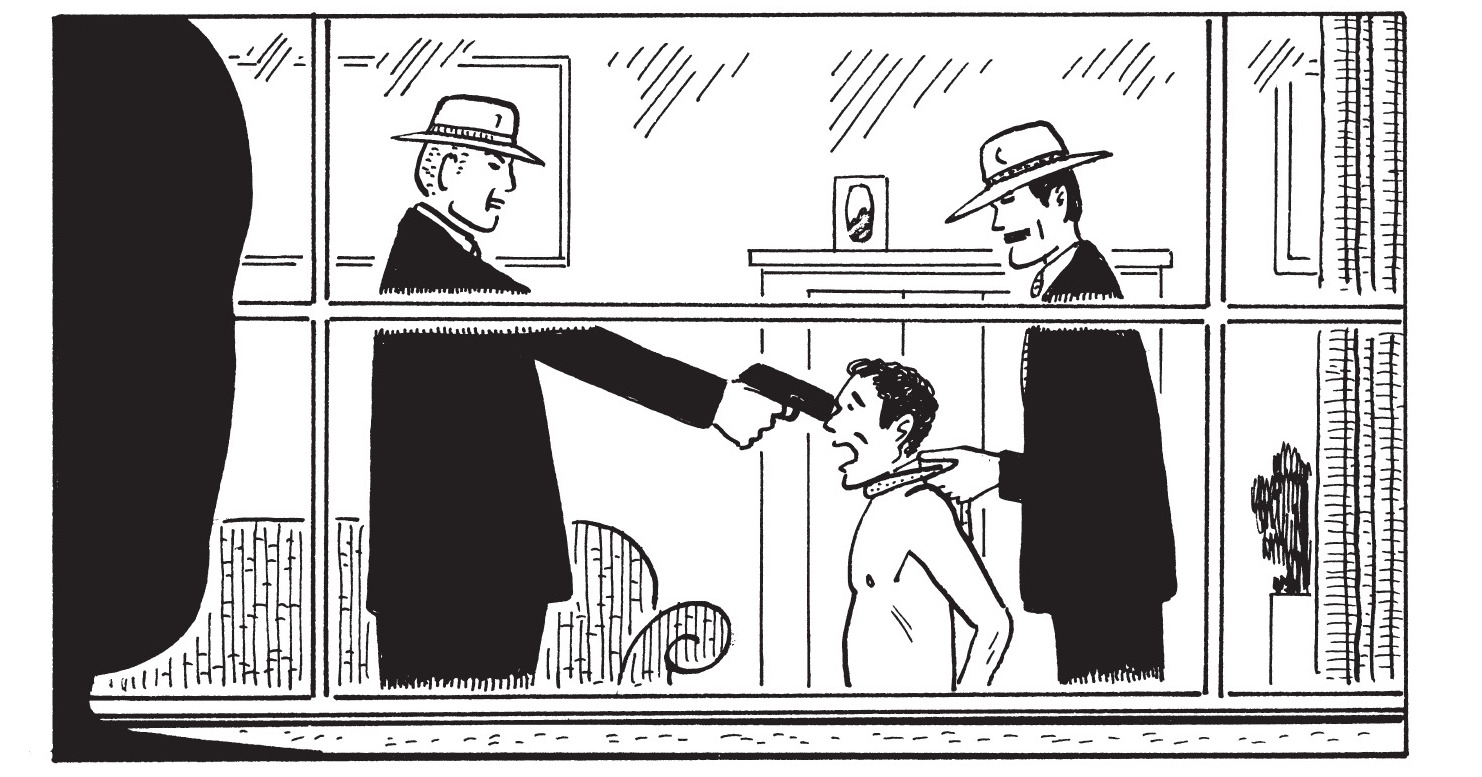

On the surface Maria M. plays like a crude knockoff of other, more prestigious crime films. The unholy mix of mob drama and family life resembles The Godfather—on steroids. There’s a salaciously brutal murder that makes the ear slicing in Reservoir Dogs look like an episode of Murder, She Wrote. The nudity and sex—so racy you’ll blush like a teenager caught watching late-night Cinemax—is as hot and heavy as anything in Body Heat. Is using the barrel of a pistol as a dildo in bad taste? Sure, but it’s intentionally bad, which is another way of saying it’s camp.

On a deeper level, Maria M. turns schlock into something loudly and proudly political, although most of it rehashes stuff you already know. The movie opens with a montage of Maria’s wide-eyed arrival in America. She spends the first third or so flitting from one crappy job to the next, and just when you think things can’t get any more meta, she lands a gig in a porn flick. On set and off, Maria sleeps with every man in sight, sometimes against her will, without thinking too much about whether the sex is consensual. The risk is that Hernandez comes across as shamelessly misogynistic to anyone unfamiliar with the complex women of Palomar. Yet the long history of objectifying women on film shouldn’t be ignored—a point he drives home by depicting Maria as all curves and no character.

Eventually, Maria meets and marries an aging patriarch of a Latin crime family. Add his son and eventual heir (and Luba’s future father) to the growing list of men who fall victim to her charms. It all leads up to the wildest shootout since Tony Montana buried his face in that pile of coke. If this sounds insanely over-the-top—well, it is. But what at first seems like a film full of clichés ultimately deepens into something more. Hernandez is celebrated for bringing diversity to comics, where Latinos remain underrepresented. This time around he flips the script. Painting immigrants as blatant criminals plays to stereotype, and whether it comes from Hollywood or Fox News, it’s pandering at best, racist at worst. Hernandez—this can’t be stressed enough—deserves all the credit in the world for taking a stand, but wokeness alone does not a great writer make.

That Maria M. is a minor work in no way diminishes the scope of what it achieves. Nearly forty years in, the Palomar series has grown into some of the most boundary-pushing fiction of any stripe—comics, film, literature, you name it. To put things in perspective, imagine a novel-as-film sequel to The Sound and the Fury, telling Caddy’s side of the story, with her daughter, Quentin, in the starring role. Every writer should be so lucky to have the imaginative chops that Hernandez shows in Maria M.

Robert Rea is the Deputy Editor and Web Editor of SwR.

More Reviews