Our Eternal Debasement

Reviews

By Federico Perelmuter

The dictator novel was a bulwark genre of Latin American literature’s Magical Realist generation, the dictator the region’s paradigmatic scourge during the Boom’s peak years (1960s through the 1980s). Famous iterations include Colombian Gabriel García Marquez’s Autumn of the Patriarch, Paraguayan Augusto Roa Bastos’s I, the Supreme, and Cuban Alejo Carpentier’s The Recourse to the Method. That unofficial triad was published in the 1970s, when mostly exiled authors fought their nations’ vile figureheads—Pinochet (Chile), Videla (Argentina), Stroessner (Paraguay), Trujillo (the Domincan Republic)—by satirizing the psychic absurdities of authoritarianism.

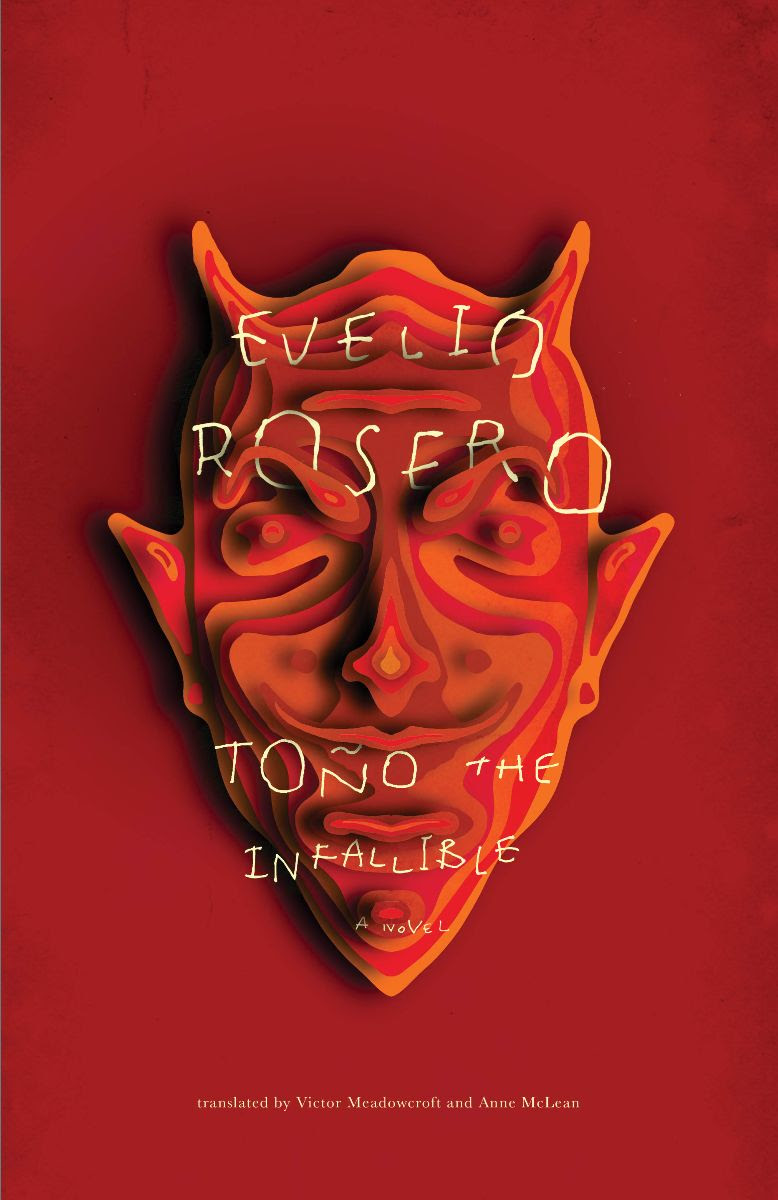

Evelio Rosero’s Toño the Infallible, which the Colombian author published originally in 2017 and Victor Meadowcroft and Anne McLean recently translated for New Directions, is not so much a dictator novel as its inheritor. Narrated in the first person, it describes the horrifying relationship between a writer, Heriberto “Eri” Salgado, and the titular Antonio “Toño” Ciruelo, his disturbing and mysterious childhood friend. Though part of a much younger generation than Marquez or Carpentier, having been born in 1958, Rosero’s project bears great resemblance to theirs.

The novel begins when Toño suddenly appears, after decades of separation, at our narrator’s door: he needs to take a massive shit. We soon learn that he has murdered “La Oscurana, the Shadowy One,” the mysterious and silent indigenous woman he married years before. In a Proustian flash of recovered memories and a guilty panic, Eri writes:

There is so much to talk about—where to start?—but it is necessary to talk, and as soon as possible, even if to do so I may need to dwell upon adventures and misadventures which, at first glance, might appear meaningless: that wedding in Barranquilla, for example, or the miraculous grotto, or the ranch of freedom; they are not meaningless, however, as the ending will have to demonstrate.

So he recounts their problematic friendship, begun in school. Toño, their friend “Fito” Fagua, and himself were their grade’s readers, all of them “freezing on the Russian steppe,” literarily, together. Toño’s father was “an important senator . . . because there are senators who aren’t,” and the teenaged Toño spreads a rumor that he cross-dresses. Toño disparages Lewis Carroll and Nabokov for their prudishness and goes into lengthy detail about his violent childhood sexuality. In fact, sexual aberrations abound in the Ciruelo family home, from apparent incest between Toño and his older sister to that same sister’s attempt to rape a terrified, albeit later thrilled, Eri. Toño’s sister dies quickly after Eri meets her: “fell into an abyss,” whatever that means, the first of many tragedies.

Inexplicable violence follows Toño, or perhaps he chases violence around, every bit of gore intensified by Rosero’s vivid prose. Eri, stupefied by mystery, trails Toño into a miserable adolescent journey across Colombia that ends in near starvation for everyone but Toño. Ultimately, a hail of bullets—the result of Toño’s penchant for provocation and Eri and Fagua’s pathetic torpor—chases them out of a small fishing town and back to their families.

To some extent, Rosero identifies Toño as the epitome of Colombia’s darkness and rancor, the prodigal “son-of-this-country,” as Eri calls him at one point. Toño is Colombia, brutal and disturbed, perverse, inexplicable, irreconciled, mysteriously enchanting. A violent conflict has divided Colombia between government forces, guerrilla armies and paramilitary groups, and drug cartels since the 1960s, though a dictator per se has never ruled the country. Only under such conditions of diffuse legality and obscure power could a man like Toño endure and thrive so perfectly immune.

Although Toño is no dictator, he is a privileged son—a child of power, its corrupt byproduct. More to the point, he’s prone to a dictator’s obscure maneuvers, shady dealings, and strange silences. Eri’s guilty fascination, meanwhile, cannot cease, oscillating between semierotic attraction and the eagerness characteristic of self-hate. Toño: Eri’s unconscious returning like a fetish under the always-failing umbrella of shame.

Fagua and Eri leave Toño behind in the fishing village, and after returning home, grow apart. They meet again when Toño asks them, separately, to pick him up from the airport and both show up. Arriving early, Eri and Fagua head to a nearby bar for a drink and some reminiscences which quickly turn sour. As teenagers, an unknown assailant once nearly raped Fagua’s sister. She was saved only by the fortunate intervention of a neighbor. Toño was that assailant, he claims, something Eri always suspected. But Fagua admits that he loves Toño; that he is utterly subservient and has completely surrendered to Toño’s whim and enchantment.

That is my tragedy. My eternal debasement. My humiliation . . . It’s horrible how, in an instant, our lives can change, or life changes us and . . . it happens from one moment to the next . . . we simply discover who we are, to our own surprise, eternal shame, unhappiness—or joy?

Eri does not really grasp the gravity of Fagua’s grim confession. He dismisses its importance and insists that, if Fagua wanted, he could turn this experience to his advantage. Although Toño terrifies both men, Eri cannot but see Toño and his actions as literary gold, good writing material. Fagua, not a writer, leaves before Toño lands.

Long periods pass between Eri’s sightings of Toño, and each successive event tests his morality further. Most supremely, Toño’s apparent death on his couch the morning after confessing to La Oscurana’s murder. He leaves concrete instructions—his body is to be left out on the street, and Eri is not to intercede beyond this small favor. Minutes after doing so, Eri finds Toño’s notebook, “a gift like a fatal shudder” which Eri, entranced as ever, transcribes into the book we are reading. He includes Toño’s quasi-manifesto, a disturbing first-person account of his brutalities. Can the testament of such a horrible man, to whose atrocities the prior 200 pages are devoted, appear to us distantly? Is Eri himself critical and observant or subservient and foolish? Can any writer be one without the other? The dictator novel’s most luminous exemplars articulate the relationship between power and language to question the position and function of writing under and about such regimes. Eri, however, is forever failing his alleged ideals. Wracked by the guilt of spineless observance, he can do nothing but move on to the next chapter. The Faustian bargain, the tragic impurity of the artistic soul, or the facile arrogance and self-interest of a writer desperate to produce, to sell, to win awards by whatever means—which is it?

Federico Perelmuter is a writer from Buenos Aires.

More Reviews