Weird, Bloody Magic

Reviews

By Gabino Iglesias

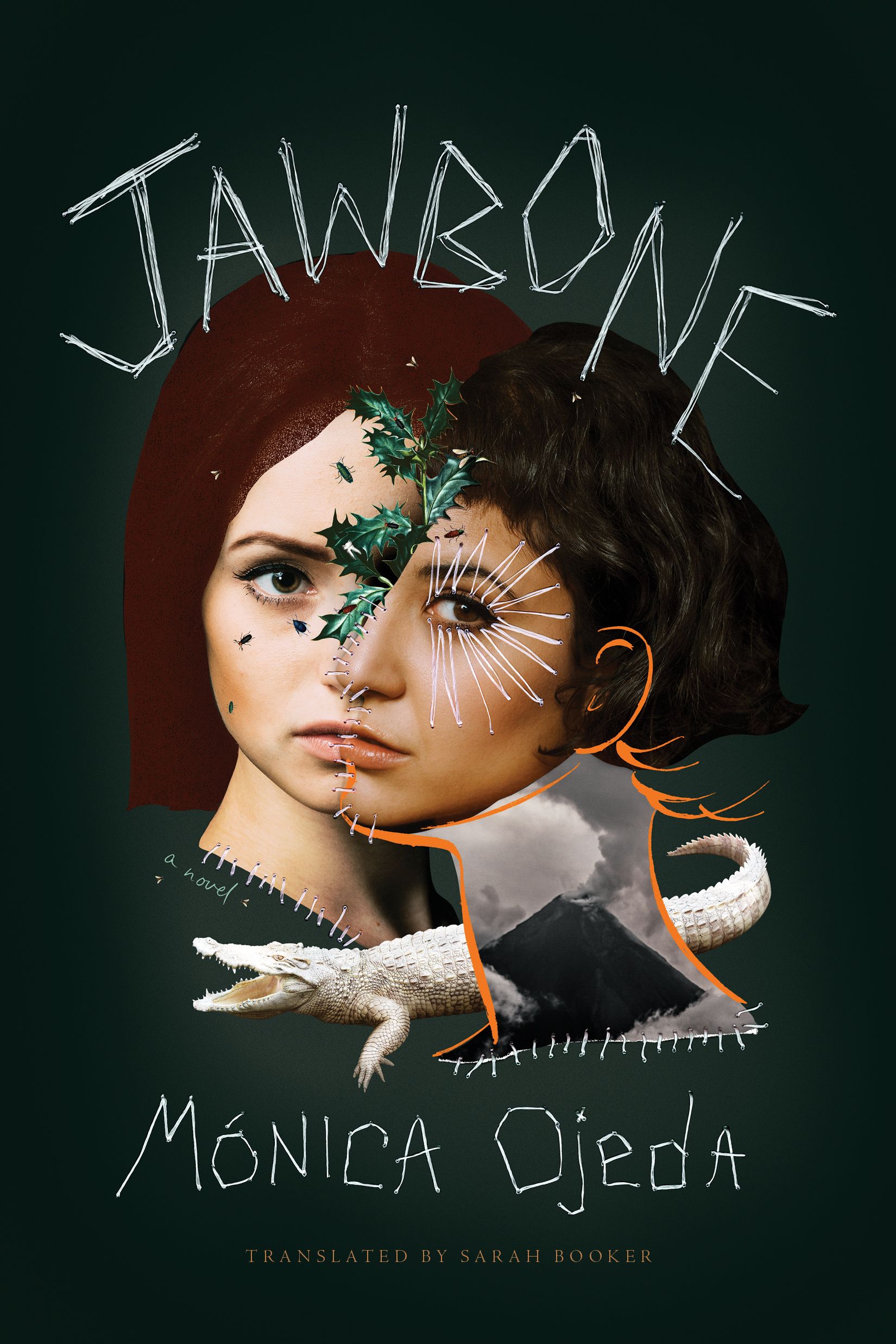

Ecuadorian novelist and poet Mónica Ojeda’s Jawbone is a wild, dirty, surreal, creepy narrative. But it’s also a sensitive novel about teenage girls transitioning into womanhood, a teacher struggling to cope with trauma, the fraught relationship between mothers and daughters, and how everything that happens early on in life can shape individuals.

Fernanda, Annelise, Ximena, Analía, Fiorella, and Natalia are all friends, but what Fernanda and Annelise have together goes deeper than friendship. Fernanda and Annelise share things in a way they don’t with the rest of the group, and not all of them are healthy. The girls attend the Delta Bilingual Academy and hang out in an abandoned house in the woods after school, a critter-filled place far from adult supervision and the realities of their homes. At school they like to push the envelope and test the limits, especially with Miss Clara, a new teacher who left her previous school under scandalous circumstances. However, Fernanda and Annelise take it even farther than their friends when they’re alone together, going deep into a place where love and pain are tied together.

Jawbone consists of two intertwined storylines. The first one follows the friends as they navigate two very different worlds. In the first, Fernanda, Annelise, Ximena, Analía, Fiorella, and Natalia go to school, ignore or suffer their wealthy parents, party with older boys, make fun of their teachers, listen to Lana Del Rey and Lady Gaga, watch YouTube makeup tutorials, and dream of modeling like Kate Moss. In the other world, they hang out in the abandoned house. There, they hurt each other physically, creep each other out by sharing horror stories and creepypastas, and perform strange rituals to the White God, a supernatural drag queen invented by Annelise.

The second narrative follows Miss Clara, the girls’ new literature teacher. At her previous school, Miss Clara was kidnapped and tortured by two female students. At Delta, she’s constantly on the verge of an anxiety attack as she fights her nerves and newfound dislike for her students. To make matters worse, she can’t get over her strange, broken relationship with her dead mother, whose voice she constantly hears in her head. Clara is convinced she’s morphing into her and starts dressing like her. The girls and Clara collide in and out of the classroom, and the aftermath of those collisions eventually results in another kidnapping.

Jawbone is one of those narratives in which a coherent plot and a satisfying resolution aren’t part of the equation. The magic here—the weird, bloody magic—is in the telling. Ojeda is more concerned with reconnoitering the inner landscape of puberty than with answering questions, even if she offers a lot of information in the process. Digging around doesn’t always lead to a treasure, but you can find many nuggets along the way, and that’s exactly what happens in this book.

There are two concerns at the core of Jawbone. The first is with horror, both as a genre and a lived reality. The debate pitting genre fiction against literary fiction is dumb, and this novel, which explores the interstices between genres, shows what can happen when a writer digs deep into language while looking for darkness, for the unexplainable, for blood. Horror is everywhere here, just as in real life. The girls, for example, don’t turn into women; they turn into monsters because we’re all animals and that’s what the loss of innocence and the explosion of hormones do.

Childhood ends with the creation of a monster that crawls around at night: an unpleasant body that cannot be trained. Puberty makes us werewolves, or hyenas, or reptiles, and when the moon is full, we can see how we lose ourselves (whatever it is that we are).

The second concern at the core of this book is language. Jawbone uses repetition to create familiarity. People are described in the same way time and time again. The full name of the school the girls attend—the “Delta Bilingual Academy, High-School-For-Girls”—is repeated again and again, too. However, creating familiarity is only the tip of the proverbial iceberg. Ojeda uses language to cut into fear, change, grief, friendship, and horror. There is a brilliant essay—one Annelise writes in response to one of Clara’s assignments—that looks at horror, the work of writers like H.P. Lovecraft, and the color white. Read as a whole, Annelise’s essay adds up to a working theory of puberty that also explains, to a degree, her White God.

White, as you said in class, represents purity and light, but also the absence of color, death, and indefinition. It represents that which merely by showing itself anticipates terrible things that cannot be known. It’s such a clean and luminous color that it seems to be on the verge of becoming cloudy, on the verge of reaching its perfect pallor. In other words, white is like silence in a horror movie: when it appears, you know that something awful is about to happen. This is because it can easily be perverted and contaminated. In fact, one of the disquieting aspects of the color white is that it is pure potential, always close to becoming anything else.

The shifting narrators and their unique voices—Jawbone has been vividly translated from the Spanish by Sarah Booker, who manages to preserve Ojeda’s poetry while also staying true to how teenagers talk (“I mean,” “you know,” “of course,” “anyway,” “like”)—make for a dynamic, engrossing reading experience. Near the end of the book, this line appears: “You can’t get pregnant by gunpowder, but if you could, you’d give birth to a bullet.” Jawbone is that mother and that bullet. It births itself, feeds on its questions, kills itself, and is born into language again and again, only to ask something different and take readers deeper into puberty and familial drama—two true horrors of unfathomable darkness.

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, professor, and book reviewer living in Austin, Texas. He is the author of Zero Saints, Coyote Songs, and The Devil Takes You Home (forthcoming summer 2022). You can find him on Twitter @Gabino_Iglesias.

More Reviews