It’s good to be a Barry Gifford fan. At a recent virtual event with Gifford, Willy Vlautin talked about going into bookstores and always checking the Gs first. He’d hit Leonard Gardner, spending years hoping for a follow-up to his masterpiece, Fat City, and finding nothing. Then he’d check the Barry Gifford section, where there was usually a new book on the shelves. I’ve had that same experience, felt that same great comfort in a new work from Gifford. He’s prolific, that rare combination of literary artist and literary worker that delivers again and again.

In 2019 alone, Gifford released three books: the expanded edition of Sailor & Lula: The Complete Novels, one of his greatest achievements; Southern Nights, an omnibus featuring three of his 1990s novels—Night People, Arise & Walk, and Baby Cat Face; and The Calvary Charges: Writings on Books, Film, and Music, a revised edition of a book with anecdotal reflections on the art that influenced him. The year 2020 has brought us Roy’s World: Stories 1973–2020, collecting Gifford’s tales about Roy, a fictional character modeled on himself as a boy. Taken together, these stories make for one of the most important and moving American bildungsromans of all time. Set primarily between 1947 and 1962, they are, as Gifford has said, “a history of a time and place that no longer exists.” Many of the stories are set in the Chicago of Gifford’s boyhood, which prompted filmmaker Rob Christopher to make the accompanying film, Roy’s World: Barry Gifford’s Chicago. When Christopher came to Gifford with the idea for a film about his time in Chicago, Gifford set parameters. He didn’t want a documentary about himself. He wanted it to be about Roy. Therefore, this lovely and tender and original film was born, an investigation of Roy’s Chicago, with actors Matt Dillon, Lili Taylor, and Willem Dafoe reading excerpts from the Roy stories interwoven with Gifford’s recollections of mid-century Chicago. We hear their voices over vintage photographs and footage of Chicago, as well as lovely animated sequences. A striking and unique work, the film should be more widely available next year. And, as if all of that weren’t enough, we have a Western noir novella from Gifford called Black Sun Rising / La Corazonada that’s just—after a short delay—been released.

I was lucky to discover Gifford’s work early, and it’s been there at every turn for me over the last thirty years. First, because I was a David Lynch fan at twelve thanks to Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks, there was Lynch’s Wild at Heart. I was dying to see the film when it was released in 1990, but I knew I’d have to wait for the VHS, so I bought the book it was based on. At that point, my reading consisted mostly of Stephen King, and the economy of Wild at Heart—its quick chapters and furious strangeness—set me free. Soon after that, I started to read classic crime fiction, starting with Jim Thompson. Some of the earliest copies of Thompson books I scored at used bookstores and flea markets and sidewalk vendors were Black Lizard editions. Black Lizard was a publishing house founded in 1984 by Gifford that specialized in reprinting forgotten crime and noir writers. It’s not hyperbole to say that discovering Black Lizard was one of the most important things that’s ever happened to me, shaping who I became as a reader and writer. Those Thompson books led me to pick up any Black Lizard title I could find, which is how I came to writers like David Goodis and Charles Willeford. Gifford’s writing on film noir (collected most recently in Out of the Past: Adventures in Film Noir) was hugely influential as well. Pre-internet, I used an earlier edition of the book as a guide to help me be a film noir completist.

After that, when I went through a big Beat phase in high school, Gifford was there with Jack’s Book: An Oral Biography of Jack Kerouac. When I turned to poetry in college, Gifford’s poems were waiting for me. When I got really into Jean Rhys, I found that Gifford was a fan and had talked up her work in his prose for years. The same went for Larry Brown. In fact, when I moved to Mississippi, drawn by writers like Brown and Barry Hannah, I found that Gifford had one foot firmly planted here, too. He’d long been great friends with John Evans, the owner of Lemuria Books in Jackson, and was also close with Richard and Lisa Howorth, the owners of Square Books in Oxford. Another connection: over the last twelve years, Willy Vlautin has been my favorite contemporary novelist. Of course, Vlautin is, as I mentioned, a Gifford fan, and the feeling’s mutual. I could probably make a case that there’s no one whose overall body of work—Black Lizard, his writing on film noir and culture, his collaborations with David Lynch, his poetry, his fiction, his reflections on literature—has shaped me more profoundly than Barry Gifford’s.

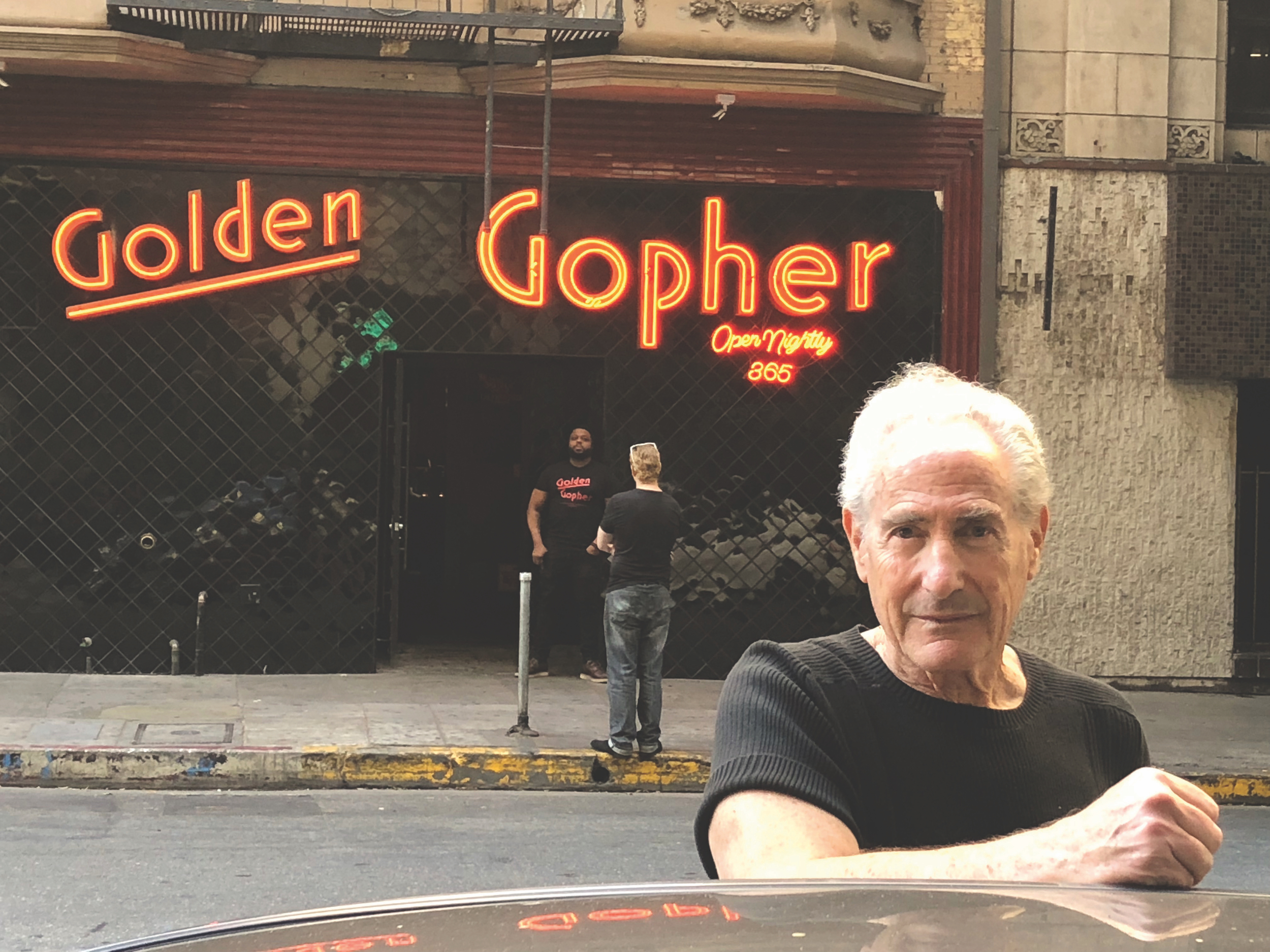

I recently spoke to Gifford by phone. I’d met him briefly after his reading for The Up-Down at Square Books in Oxford several years ago and had a quick email exchange with him last year thanks to my editor, but this was the first time I’d had the chance to speak with him at length. Given the circumstances, I sat out in my car with my cellphone and a digital recorder to avoid interruption from my children. I love my kids very much, but they’ve been known to scream out strange things while I’m on important calls, which is usually pretty funny, but this was Barry Fucking Gifford.

Gifford and I spoke about how things have been in this off-kilter, mangled train wreck of a year. Coronavirus and quarantine. Mismanagement by an absurdly evil administration. The election. Things, hopefully, looking up with new leadership taking over and vaccines in the pipeline. We talked about my move from New York to Oxford over a decade ago. Gifford told me about his history here in Mississippi. Staying in hotels in Jackson as a kid, a life often lived on the road, driving between Key West and Chicago. His friendships with John Evans, the Howorths, Larry Brown, Barry Hannah, and Willie Morris. Gifford told me about a series of shirts that Evans had printed up that were for sale at Lemuria, featuring his drawings of Brown, Eudora Welty, William Faulkner, Jim Harrison, and Willie Morris. (It’s worth noting, in this especially difficult time for indie bookstores, that these shirts are for sale via Lemuria’s online shop—I immediately ordered the Brown shirt.) Gifford talked about meeting a young writer named John Grisham in 1989 or ’90 at one of his readings in Mississippi. Grisham was selling self-published copies of A Time to Kill out of the trunk of his car. He and Gifford spoke for a while, and Grisham was thankful for his time, complaining that most of the writers he met were snobby and wouldn’t give him the time of day.

My questions for Gifford were rambling and full of nerved-up admiration. How do you sum up a lifetime of fandom in an hour-long phone conversation? It’s impossible. I tried to focus on Roy’s World. Gifford published the first Roy stories in 1973, but he started writing them in 1957, when he was eleven. The Roy stories are not an exercise in nostalgia. They are succinct, not overloaded with reflection. Now does not impose itself on then. The first Gifford book I encountered that featured Roy was Wyoming, a short novel about Roy and his mother traveling around the country, told only in dialogue. The Roy stories, frankly, are a relief to read. They aren’t churned out on an assembly line. Nor are they full of overwrought language and neat epiphanies. They are, as Gifford says, “fiction, invention” rooted in memory and emotion. There is, as is the case in all of his work, a real joy in names and naming. While the film Roy’s World focuses on Roy’s (and Gifford’s) childhood in Chicago, the stories take us everywhere. Even as a boy, Gifford was worldly, shuttling between Cuba and Key West and Chicago and New Orleans. Gifford’s father was involved in organized crime, and his mother was a former beauty queen. Colorful characters surrounded him, and there’s no doubt those folks—in myriad ways—wound up inhabiting Roy’s world. Gifford’s America is mythical and lively, the America of stories unwinding like highways, ribboning from coast to coast.

I asked Gifford about his original vision for Roy, what drove him to this character and this particular stretch of time. “I started writing Roy stories when I was about eleven,” he said. “Even before I was in high school, I used to write similar stories. They were humorous but very odd. Strange characters. I remember an older brother of a close friend of mine, he found the stories, some that I’d given to my buddy Magic Frank, and he said, ‘These are really unusual. You have a strange imagination. I like these.’ So I just kept on doing it. Finally, I published the first group of them in 1973 in a book called A Boy’s Novel. Over the years, of course, I’ve gone in several different directions—I pursued whatever interested me—and when I came upon Sailor and Lula, little did I know that it’d stretch out to eight novels. I also wrote the books included in Southern Nights. But, periodically, I would go back and write more Roy stories. After The Sinaloa Story, I decided I was done with that sort of hard-nosed book—dealing, as I saw it, with the crimes of our time, racism and fundamentalist religion—and I didn’t want to live in that world anymore, so I decided to get back into Roy’s world. And that’s what I’ve done.”

Gifford believes the Roy stories to be his true legacy. “The structure is most interesting to me,” he explained. “It’s not illogical. It’s elliptical. What it comprises, really, is one big ongoing novel. I’m very happy living in that world. The character of Roy is sort of never-ending, as far as I’m concerned. After Roy’s World, I figured that’d be the end, but here I am deep into a new Roy book. It came along at the right time, given the lockdown status of our life due to the virus. I go to work every morning. I sit down in my studio, and I work.”

When I asked Gifford about where he starts with the Roy stories, his answer was pleasantly evasive: “Really all I need is the first sentence. I don’t like to analyze this very much. I don’t like to know what’s going to happen. I like it to remain a mystery. I didn’t go to a writing school. I didn’t go to college very much, except for a year to play baseball at the University of Missouri. I don’t have an academic background. But I loved to read from a young age and I started early on my own. I don’t like to know the ending of anything. I’ll let it go where the characters take me. I’m always trying to make it new, as Ezra Pound advised. How I achieved my own education is by going to people who I thought had something to tell me or teach me, to point me in the right direction, to say, ‘Read this’ or ‘Go watch that film.’ The most important thing is curiosity. That’s the one thing you don’t want to lose. You need to retain the spontaneity.”

About process and experience, Gifford had this to say: “I was never the kind of person who would belabor it. If I didn’t feel like writing, if it wasn’t ready yet, I just didn’t do it. I still don’t. I’d rather go to the racetrack. That’s really how I’ve been my whole life. As my son said to me, ‘Well, Pop, I admire the fact that you’ve always done what you wanted to do.’ I said, ‘Well, my one ambition was to never work for anyone else.’ I had a family very young. Of course, I had to work. I did many things. I’ve been working since the age of eleven. I had a mother and little sister to help support. Later, after reading about Joseph Conrad and Herman Melville and Jack London, people who were my models early on, I was a merchant seaman. I worked as a truck driver. I worked in a produce market, delivering onions and potatoes. I worked in construction. I always wanted jobs where I could still do my writing in my head. I always had that focus and the ability to concentrate. Other than curiosity, that’s the key. The ability to concentrate and get it done.”

While he didn’t grow up around readers and writers, he did have musicians and artists in his family. More than that, because of the world his father was involved in and because of all the traveling he did with his mother, a rich tapestry of voices enveloped him. “I was always around people who had stories to tell,” he said. “They were fascinating for a kid. What interested me was the way people spoke. The dialects they had. So many of the people I was around were not native-born Americans. Everybody had their own way of talking, of explaining things. That was my education. That’s what I developed over the years. Not just replication, but invention. Half the time, these people were inventing a large part of what they were saying. As Proust said, ‘Literature is the finest kind of lying.’ I’ve always had that pasted up on the wall. You’re free. That’s why fiction is so terrific in terms of a form. It means you made it up. You can say and do anything you want with it and take it in any direction.”

One of the things about Gifford that I’ve always valued is his wide range of taste. With the creation of the Black Lizard series, he took genre fiction seriously. He did the same with film noir, ahead of the curve in celebrating B pictures of the 1940s and ’50s. I asked him to talk about how he discovered this stuff early on, what shaped his tastes. “I traveled a lot, mostly with my mother, and we lived in hotels,” he said. “I was left alone much of the time. Left to my own devices. In the hotels, I would sit around in the lobbies or out by the swimming pool, listening to people from all over the world tell me about their lives. I’d stay up late at night, watching movies. Mostly old black-and-white movies. I learned my sense of narrative and storytelling through those movies. Of course, watching foreign films, which my mother liked to go to, I realized you could create your own structure. Since it was fiction, you could go in any direction. The ones that attracted me significantly were the noir films. It coalesced with my father’s life in organized crime and the world that I saw around him. When it came to crime writers and film noir—that was a significant portion of where my interests took me. I read so many crime writers off the wire racks of drugstores as a kid. I read Jim Thompson at twelve years old. David Goodis, too. When I began spending time in France, I saw that there was the Série noire imprint. That’s when I created the Black Lizard series. The idea was to deal with writers who had a psychological edge that wasn’t often reflected, writers that had interesting perspectives and crazy ideas—they weren’t just potboilers.”

We then talked a bit about his experiences writing for film and TV, about works that had been adapted and others that had stalled out. I took this opportunity to ask about the recently published Black Sun Rising / La Corazonada, which Gifford had hoped would become a film. “When I was a kid, in Florida, I grew up around a lot of the Seminole Indians,” he said, delving into the origins of the novella. “Kids who were working on alligator and reptile farms. I became interested subsequently in the history of the Seminoles, the only tribe that never surrendered to the federal government. They just retreated further and further into the swamps, into the Everglades. Their history fascinated me. When I read up on the Black Seminoles and found out about this first integration in terms of the tribes, which eventually happened in northern Mexico, I wanted to write about them, to tell that story. So, I wrote the novella.” Jim Hamilton, who had been one of Sam Peckinpah’s main writers (Gifford dedicated the book to him), thought it was a great idea for a film and they worked on developing a screenplay together. At the time, the interest wasn’t there for a Western and then Hamilton passed away. Laura Emilia Pacheco, who had previously translated some of Gifford’s poems and Roy stories, translated the book into Spanish, and Almadía Ediciones published it in Mexico first. It’s now available in a beautiful dual-language edition from Gifford’s New York publisher, Seven Stories Press.

Our conversation took us to several other places—New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, back to Mississippi, France—and I was excited to hear more about the upcoming Roy book Gifford had written during this quarantine year: The Boy Who Ran Away to Sea. “Carnival,” appearing in this issue of Southwest Review, is one of these new Roy stories. In this book, Gifford’s illustrations, which have become a more frequent presence in his output over the past decade, are a substantive part of each chapter and inform the text.

Talking to Gifford—hearing about his discipline, his writing habits (he writes longhand in cursive) and process, the curiosity and spontaneity and wonder that feed this vast world he’s made—was exhilarating. When we ended our call, I went back to his books. I heard his voice on the page. I sat down at my computer and felt truly excited to work on my new novel after hitting a rough patch on it for a week or so. The best writers make you excited in that way.

It’s good to be a Barry Gifford fan. ![]()

William Boyle is from Brooklyn, New York. His books include Gravesend, which was nominated for the Grand Prix de Littérature Policière in France and shortlisted for the John Creasey (New Blood) Dagger in the UK; The Lonely Witness, which was nominated for the Hammett Prize and the Grand Prix de Littérature Policière; A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, an Amazon Best Book in 2019 and winner of the Prix Transfuge du meilleur polar étranger in France; and, most recently, City of Margins. He guest-edited the noir volume of Nicolas Winding Refn’s byNWR.com. He lives in Oxford, Mississippi.