This happened in the sixties, in a town on Mexico’s Costa Grande called Técpan de Galeana. Dad was sixteen and my uncle Julián fourteen. On the weekends, they used to work in my grandmother’s copra orchard.

A copra orchard is a sloping coconut plantation. The fruits are chopped and opened using machetes; you split them in two and drain off the liquid or drink it, and then leave the two halves in the open air. When the white, sun-dried meat known as the copra is ready, you grate and boil it to remove the oil. Depending on how good the harvest is, you then either sell the oil from door to door or send it to a factory in Acapulco, where it’s made into soap.

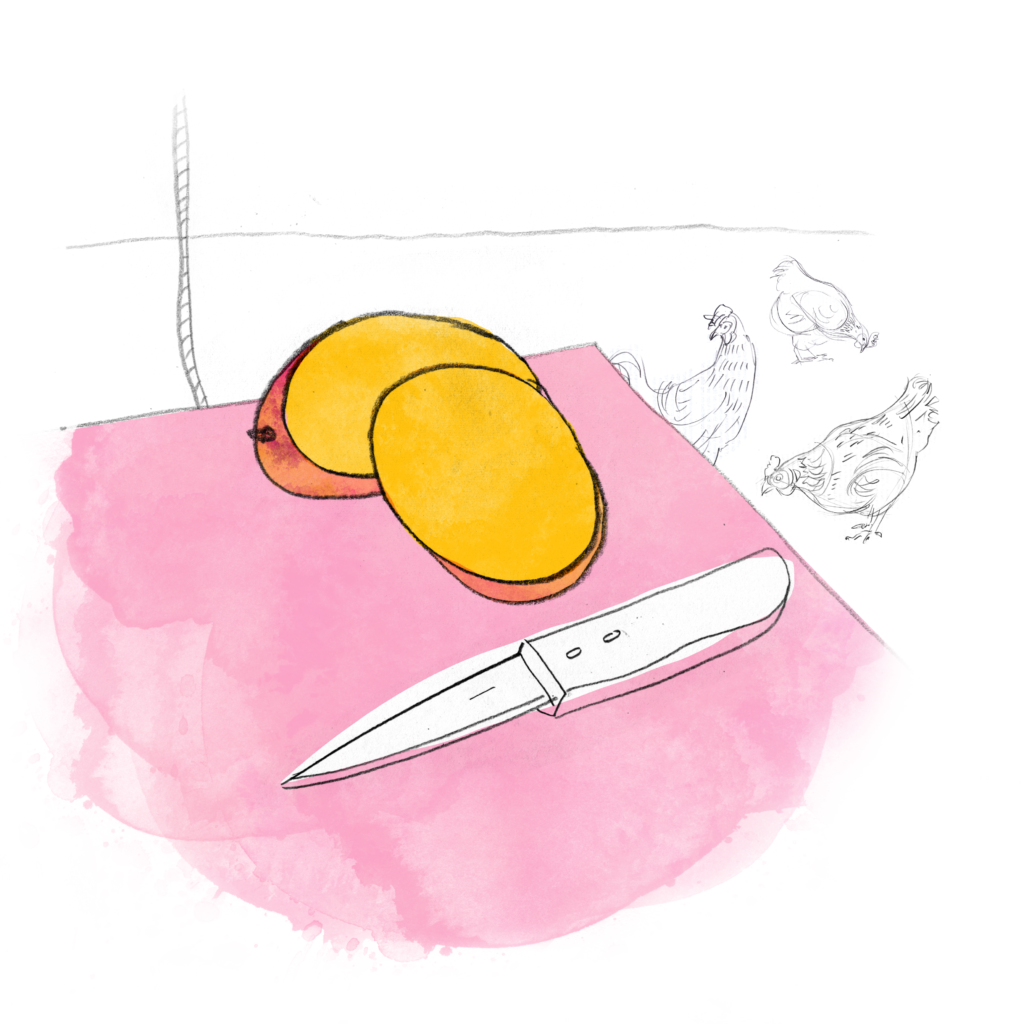

Grandmother’s orchard was small enough for two young kids to be able to take care of it on Saturdays. The tough days are when the green coconuts have to be harvested, peeled, and split; the easy ones are when you’re just there, watching to make sure the birds don’t peck the copra. There are wild birds but also domestic fowl, because what else can you do in a plantation of trees that practically grow without human assistance besides raise a few chickens? What else can you do besides raise chickens and lie in a hammock? And eat mangoes? Raising chickens, lying in a hammock, and eating mangoes are three things that coastal dwellers have got down to a fine art.

This happened in the mid-sixties, in my grandmother’s copra orchard, on one of the easy Saturdays. Dad and my uncle Julián arrived early in the morning. They put their belongings under a mango tree to keep them from the sun, though not from the muggy heat, took out their hammocks, and strung them between a branch and a pole fitted with hooks. Then they lay back to work. And so the day progressed until three in the afternoon, by which time their stomachs were growling. They opened their bags and took out the buns with relleno de cuche their mother had put together. A bottle of Agua Yoli. A flask of cold chilate. A couple of tecoyote biscuits.

“When life’s this good, who’d desert their post?” my father must have asked. It was his favorite phrase for chewing the fat. Or that’s what my mom used to say. The truth is that I only ever met him once or twice. Mom told me this story, and she heard it from him when they were dating.

After their meal had settled a little, Uncle Julián and my father returned to work.

“Hey, man, go check the birds aren’t eating the copra,” ordered my father without getting out of his hammock.

“No can do, pardner,” replied my uncle Julián without getting out of his hammock.

“What’s stopping you, man?” insisted his elder brother from his hammock, serenely angry: I’m not sure if this is true, if it’s just my family, all coastal people, or something to do with growing up without a father, but you wouldn’t believe in what high esteem people on the Costa Grande hold the rank of Elder Brother.

“I’m fishing a ripe mango,” said Julián.

“Ripe mango, my foot! They’re all still green.”

“To be sure, there’ll be one.”

Dad looked up to the top of the tree in case his shortsighted eyes managed to spot a ripe fruit among the branches. As if: the season didn’t start for another fortnight. You could fish a green one using a fruit picker (a two-and-a-half-meter pole tipped with an open-weave cane naza—a sort of creel with a claw inside: you raise the pole, trap the fruit, tug, and the mango falls cleanly into the naza) and then eat the slices with chili and lime. But that’s all it was good for.

“There’s no ‘sure’ about it. Just go check, will you, man? I can hear the hens.”

“I’m busy, pardner.”

Dad calmly began to get really mad.

“Hey, little bro, if you don’t go check, I’ll hang you.”

“Hang me then, pardner. I’ll fish a mango while I’m waiting.”

I don’t know where he got the idea. Maybe from the red tops.

He stretched over to his bag and took out the long piece of rope he had there for some reason or other: could be that it was part of his equipment or that his mind had been stalking the idea of killing his younger brother before they set out. First, he started to tie a slipknot. Slowly, slowly, still lying in his hammock. That went on until five in the afternoon. Second, he began tossing the lariat at his brother’s neck. If he didn’t manage to lasso him, that was partially because Julián—still fishing his mango, an activity that required a level of mystical concentration—dodged the trap by dipping his head every so often.

Dad finally got tired of trying to achieve his aim from the hammock. He slowly extracted himself, walked over to Julián, and passed the noose over his head. Julián didn’t turn a hair.

“This is your last chance. Go check the copra and the hens.”

“No can do, pardner.”

Dad looked up in search of the ideal branch for lynching his brother. Once again, his shortsighted eyes betrayed him: he wasn’t sure which fork would bear the weight of a fourteen-year-old boy. That was the kind of thing the eagle-eyed Julián took charge of.

“You didn’t think that one through, did you, motherfucker?” said my uncle, reading his brother’s mind.

Dad passed the rope over a lowish fork that seemed to be pretty well aligned with the trunk. Now all that was needed was to see if a single person would have the strength to haul Julián—well built if not to say fat for his age—up on the pulley. But before he could do that, there was the matter of putting on his work gloves to stop the rope from cutting his hands. Added to that was the matter of finding a long slope to carry Julián’s body down, and running off, pulling on the rope with all his might. And then, too, there was the matter of putting a piece of sacking over his shoulder and winding the rope around his torso so he could use his whole weight to complete the task without the aforesaid rope burning him. And hoping to goodness that the aforesaid rope was strong enough not to fray on the first contact with the wood. He discovered that punishing insubordination required an incredible amount of labor and energy. Just working it out made his head hurt.

“You didn’t think that through either, did you, motherfucker?” my uncle laughed, again reading Dad’s mind.

Dad donned his work gloves, armored his chest with the sacking, wound the end of the rope around his hand, and was ready to start running down the slope when my uncle pointed to a spot in the mango tree.

“There it is, pardner. I’ve caught it. Quick, pass me the picker.”

Dad suspected that my uncle was playing a last-minute trick in order to save his life, but what the hell, he decided, if it also saves me from so much slog for sweet fucking all, just to teach that disobedient bastard a useless lesson; Cain must have been thinking what a pain it all was when the moment came to kill Abel.

He dropped the rope and passed his brother the picker, which was lying two or three steps away. Without getting out of his hammock, Julián raised the pole and fished the mango. Then he lowered it and carefully inspected the contents of the naza. It was a plump, yellow, smooth little fruit, without a single black mark.

“It’ll be a bummer,” my father prophesied.

“Lend me your knife,” replied Julián.

My uncle Julián cut the mango in two and offered one half to his elder brother. Dad said (I didn’t get this from my mother: I heard it in my father’s own voice years later, just before he died, when we finally got to know each other personally) that it was the sweetest, softest, juiciest little mango he’d ever eaten. Out of season. An aberration.

Dad returned to his hammock to better enjoy his half of the fruit.

And that’s how my grandmother found them when she arrived to take them home; torn between the rage of finding them lying in their hammocks, sucking on the mango while the birds pecked the copra, and fright: they were so at ease that it hadn’t even entered their minds to remove the hangman’s noose from around uncle Julián’s neck. ![]()

Julián Herbert was born in Acapulco in 1971. He is a writer, musician, and teacher, and is the author of The House of the Pain of Others and Tomb Song, as well as several volumes of poetry and two story collections. He lives in Saltillo, Mexico.

Christina MacSweeney is the translator of Bring Me the Head of Quentin Tarantino, The House of the Pain of Others, and Tomb Song by Julián Herbert, and has published translations, articles, and interviews on a wide variety of platforms and contributed to several anthologies. She was awarded the 2016 Valle Inclán Translation Prize for her translation of Valeria Luiselli’s The Story of My Teeth. She lives in England.