We make our way under a white sky, in the footsteps of a peasant and his mare. The latter carries our backpacks, strapped to the saddle, while the former wears a hat on his head and a walkie-talkie on his belt. Soles and hooves sometimes sink into the earth, humid from a recent shower; four electrical cables sever an archetypal nature. Mountains capture the eye with their muted greens. Two dogs follow us and others bark as we pass by. From a row of corn, an indígena waves at us—this is the term in use here, ill-sounding to French ears after the Code de l’indigénat,[1] but a term claimed as their own by those it concerns most, in front of a world that thought good, having “discovered” them, to name them “Indians.”

The community to which this peasant—whom we met at a location agreed upon in advance—belongs reveals itself after a ninety-minute walk. A few tin roofs at first, a steep gravelly trail, and then a small square in the guise of a basketball court. We’ll stay a few strides away for the next fifteen days, in a hovel bearing the colors of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, the EZLN. A large portrait of Ernesto Guevara (“Hasta la victoria siempre”), chipped at eye level, and a bust of Emiliano Zapata (“Tierra y Libertad”), rifle in the right hand, frame a wooden front door, dilapidated but obstructed by a metal chain. “Justicia – Libertad – Democracia,” the facade reads: large white capital letters against an all-black background, pierced by a red star in the middle. The four windows, wrecked, remind one of arrow slits. The man gives us a key and his hand to shake. “Compañeros.” Comrade: the word never ceases to amaze me—the only word liable, as soon as it’s pronounced, to turn a stranger into one’s fellow.

We drop our belongings on a concrete slab, guiltily thanking the animal for the help it gave against its will. The hall is vast and high under a sloping ceiling. A number of chairs appear to wait, in vain, for the rare visitor. Three other small rooms make up our new home: a sort of kitchen with no electricity, a disused bathroom, and a sordid closet with a toilet inside. We divide the space (Jules P. takes the platform at the end, me the middle and the wood table), then unroll our sleeping bags on the floor before stacking books and notebooks nearby—we’ve been traveling in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, for a month. On the walls, traces, drawn or painted, of previous volunteers for the non-state Civil Observation Brigades, which brought us here: “Free Palestine,” as well as Zapatista, anarchist, and ETA emblems.

At night, the Commission—four Indigenous comrades—pay us a visit to welcome us and answer prospective questions. The community counts three grocery stores (enough to buy the necessaries to cook over a wood fire, in the shed outside intended for that purpose), and we take note of its political or factional infighting as one would of geographic boundaries. A villager, Zapatista, was recently shot by paramilitaries; it’s one of the reasons we’re here: an all-too-modest internationalist solidarity, taking notes on the situation, bearing witness in the event of clashes, drafting a report on human rights. The compas (diminutive for compañeros) keep constant guard and communicate, from one end of town to the other, via radio transceiver.

A lamppost illuminates our dwelling’s surroundings. Dogs, muzzles thin, emaciated and famished, hazard a few steps—fearful at first, tails low, fleeing over small nothings. They’ll be sleeping closer to us before long: more so every day, in fact, with every bit of food we give them. One of them, a heart-rending female with sunken breasts, protects two or three puppies who rarely venture farther than the basketball court.

The moon is round, this first night: a candle high, holding its own in acid black.

The animals howl at her, distant memory of wolf blood; crickets make their night, populated, chirping. Lying down, head sunk in my rolled-up mesh jacket, I read the memoirs of Margarete Buber-Neumann, deported to Soviet Siberia at the end of the thirties. The failure of barracks Communism does not signal the end of the emancipation of the living, only the necessity of rethinking the question of power, more or less to the core: Zapatism has been trying since the mid-nineties . . .

![]()

I first met up with Jules in another community, non-Indigenous and libertarian. Its members—some twenty young men and women from all, or almost all, backgrounds—practiced meditation and self-defense. Meals were communal, mostly; dormitories, a few animals, two or three kids.

From there we went to the Universidad de la Tierra, Zapatism’s urban and intellectual stronghold, south of San Juan Chamula. I browsed its library (Spanish, English, French; Zola, Breton, Sartre, Gide, Maiakovsky, Althusser, and Tintin), listened to a mixed choir honoring the memories of indígenas assassinated by the authorities (the lyrics admonished the “capitalist hydra of the government,” urged listeners to defend the “homeland” and protect “Mother Earth” from being sold), and talked to a Kurdish feminist traveling through the continent. On the walls: frescoes, photos of Gandhi and Mandela, black flags flocked with red stars, a tribute to ecologist thinker Ivan Illich.

Jules came across an old bearded man who swore to having traveled, long ago, in Jacques Mesrine’s car while hitchhiking on the roads of France; I had a friendly conversation, in some tiled kitchen corner in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, with a Podemos candidate convinced that the radical left was cutting itself off from the masses with its codes, markers, watchwords, and mythology. We spent several nights in a hostel in the company of a German anarchist working with victims of domestic violence, whose name, I’m ashamed to say, has slipped my mind as I write these lines: tall, short brown hair, eyes of a rare blue . . . She’d talked of the Invisible Committee and I of Rosa Luxemburg; she’d hailed the necessity of multiplying autonomous zones, and I the parallel possibilities of mobilizing more segments of the population: we could, it goes without saying, trade in largely reciprocal vanities of a national-historical sort.

“Zapatism is a small movement and Mexico is uninterested,” asserted an inhabitant of Chiapas’s cultural capital, the “vampire city” whose walls are sprinkled with stenciled depictions of political prisoners and freshly traced slogans from the National Front of Struggle for Socialism: “No to paramilitarization,” “Solidarity with prisoners,” “Health is a right, not a luxury,” “No to state terrorism,” “Medicine for the people” . . . A woman from Mexico, occasional spokesperson for Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos—known as Galeano since his self-dissolution in May 2014 and withdrawal from the revolutionary organization’s leadership—professed no less: “Zapatism is not just another guerrilla group, they’ve built a real autonomy. It’s been a silent plague, in the last few years. The government cannot enter their lands.”

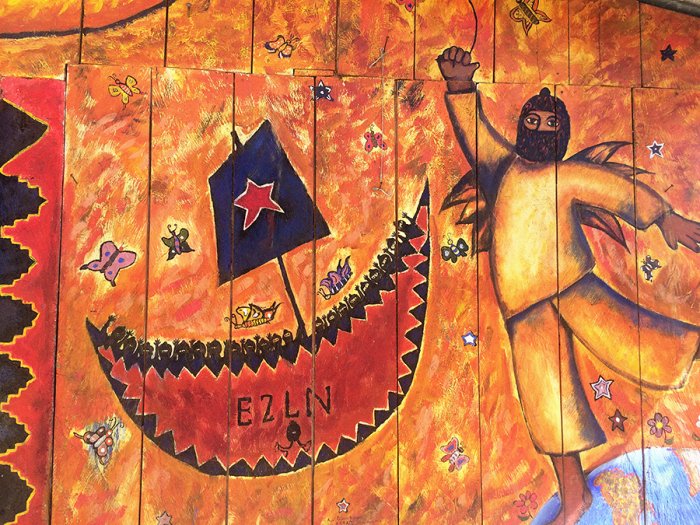

We met a painter whose work has helped forge the movement’s singular visual identity—a Chilean woman in exile, imprisoned under Pinochet’s dictatorship—and later came across a few soldiers from the Zapatista army, all famed balaclavas and sharp outfits. We then moved on to a caracol, one of five Zapatista organizational centers in the Chiapan mountains. “Para todos todo, nada para nosotros” read a sign at the entrance, in front of the guardhouse and the red-black barrier that secures the way in: “For all, everything; for us, nothing.” A salutary expression, if sure to force a smile on the faces of our own elected leaders. The men and women on guard duty wore hoods or scarves but no weapons. Journalists from the mainstream press were, one understands, denied entry: the organization had suffered from their remunerated dishonesty. The Junta de Buen Gobierno (Committee of Good Government) supervises the administrations of autonomous municipalities: positions are temporary, rotating, and unpaid—politics, here, is no profession. The municipality that accepted our visit claims to be the “central heart of Zapatism before the world.”

There, we ate every day—kidney beans and tortillas, for the most part—under the portrait of Abdullah Öcalan, the PKK leader incarcerated by the Turkish state, and slept in bunk beds usage would have us describe as “makeshift.” In the Zapatista zone, alcohol and drugs are prohibited, along with pesticides. Frescoes on every building showed a roster of national figures, but also images of sacred corn, Frida Kahlo, rebellion against the neoliberal order, the snail (caracol in Spanish: here a symbol of time recovered from surging modernity and capitalist hubris, the avatar of a revolt built stone by stone), the inevitable Che, and the African American struggle. I noted, amused, the following slogan painted in the shadow of a roof: “The algebra of revolutionary education is the dialectic.”

We had a long conversation with a number of Zapatista militants, danced—if only a little, and poorly—before attending an anticapitalist history class with a hundred boarding students, called “comrades” by their “education promoter.” “We move forward and the government doesn’t really know how to react,” confided N., in Spanish. His face was uncovered, as are those of the near-totality of Zapatistas inside caracols, when not attending semi-public gatherings. Their numbers are intentionally kept mysterious by the leadership. “A Zapatista is born every day, impossible to know,” confirmed our interlocutor, a peasant and teacher in his thirties. N. bore full cheekbones and dark, burrowed eyes, all on a face pulled hesitantly downward by a goatee. “We have neither the possibility nor the luxury of leaving, or traveling, because we have no money and we have to build our autonomy. It’s difficult to live communally, but that’s the way it is. We’re at war. But we have hope: the little ones will finish what we couldn’t. Our parents didn’t know how to read, we had no schools. Lots of babies died from simple fevers. Zapatism changed all that.”

This year, 2018, the National Indigenous Congress is preparing to enter a woman, María de Jesús Patricio Martínez, in the next presidential election: a rupture, symbolic more than anything, with the autonomist paradigm employed until then (“The struggle for power is a struggle for lies,” Marcos deemed in 2001). “We don’t want to win elections but to win comrades,” we were told. “Yes, it shocked a lot of our own, this new strategy. But the Juntas don’t care about winning votes, we just want to gain more land for the people. The candidate is a pretext. We still think that the struggle must be fought below: government, education, food, all that must come from the people. That’s the Indigenous conception of the struggle. The Mexicans in power aren’t Mexicans. They use the flag to sell their country. They don’t work for the people but for capitalism’s transnational interests. There are two Mexicos: one above, and one below. The real one is below. We are the true Mexico.”

The Zapatista landscape repudiates the ideological divisions we are accustomed to, between a right and a left that morality and practice seem to oppose; the Mexican movement speaks, as it did for a long time through the voice of Subcomandante Marcos, of those above and those below, owners and common people. The peasant-teacher had emphasized that there is no real difference between the two official camps: the left is a belated right, and vice versa. “Zapatism was born when the left had disappeared. We were born when all was dead. That’s why they saw us this way: we arrived like hope.” What kind of future does this man dream of? “A world where we eat the same things, have the same houses, where no one dies of hunger while others have too much to eat. A world without center or periphery. A world of communities, against the capitalist vision of the world, that of wealth and destruction, individualism and power, suicides and CEOs.” The Zapatistas who speak Tzotzil, a Mayan language, indeed possess two different words for “work”: ámtel and kanal. The first indicates non-salaried labor, for the benefit of relatives or the community (i.e., working in farming, in education, or in politics); the second relates to the market, the boss, hierarchical exploitation, and the sale of one’s labor-power. N. himself, educator as he may be, isn’t paid by virtue of his being a Zapatista militant: “We serve the people.”

“People come here and think that Zapatism, it’s paradise,” N. continues. “No! There are fights, things to settle between people. Or even with oneself. It’s a process. Women, for example, don’t always find it easy to escape tradition. But women that went to Zapatista schools are much more self-reliant.” Another Zapatista, a woman with straight black hair, arched nose, and emphatic eyelids, later tells us: “If you allow the destruction of nature, you allow your own destruction. We have to ask trees for their consent before cutting them down. Everything is sacred for us. People, rocks, animals, everything.”

We managed to be allowed—foreigners must submit to rather strict regulations—to visit the caracol hospital, escorted by two “health coordinators,” who were aloof, in truth, and didn’t speak a word of Spanish. An all-mustache Zapata, a smiling Che, a variegated Virgin, and a female combatant, hooded and rifle in hand, were painted on its facade. Nearby, a dog limped, while a woman nursed her child, breast uncovered. The health center counted one dentist, a medical laboratory, radiology and operating areas, and six rooms, as well as gynecological and ophthalmological services. Only Zapatistas benefited from reduced costs; the practitioners, also volunteers, were trained by an international NGO. Inside, a shrine honored, with myriad icons, the mother of Christ, and a pedagogical fresco reminded visitors of basic hygiene.

An indígena played guitar not too far away, absorbed by the mist. Workers busied themselves on some construction site, next to the church and within reach of the women-run cooperatives. In the Junta’s modest offices, where no foreigner is allowed unescorted by an assigned official, we were observed by a great painting of Subcomandante Marcos—a man otherwise rarely on display, impervious, as he says, to all “cults of personality.” On a desk, the inscription “To die decently is to die an insurgent.”

![]()

The sky, setting, curls up in its copper shell.

Sitting near the entrance of the hovel fallen to the Brigade, I think of the roadblock we passed on a nearby regional road: the taxi driver had quite simply paid off the indígenas, non-Zapatistas, who were protesting the human rights abuses they claimed to suffer, as we learned in a leaflet they made sure to hand to each vehicle. I think, also, of the crowd of villagers on the side of a ravine we’d driven along, where the body of a murdered man had just been found.

Jules returns from a walk in the vicinity, his head lost in his cigarette’s gray clouds. The days pass, identical, earthly thread of a time Man still grasps, without transfers or connectivity, tracking or big data. The “conscious”—meaning “politicized”—members of the community gather every night to discuss the village’s organization, divided as it is between Catholics and evangelicals, beneficiaries of Mexico’s state programs or those contemptuous of them.

A light breeze irritates the trees. Two aged ladies converse at the back of their garden; a dog on the asphalt savors a corn on the cob; a horse neighs, unseen; a scorpion dashes off across the shed where we blow on the embers of a capricious fire. An old man—long nose tidying up a fine, gray mustache, jeans, his chest bare save for the polo shirt thrown across his lean shoulders—invites us over to his home, on the floor of which chicks roam about. He shows us a portrait of his father, ornamented by the angel Gabriel; his wife, cracked bronze face topped by a headscarf from which two braids stick out, offers us a cucurbit and kidney bean dinner. Two of their sons have emigrated to the United States. The mother’s eyes swell with tears, in the cast shadow of a hammock, at the mention of the struggle led by this community against the government, the international companies that ogle the area, and the paramilitaries. Those last do their training nearby, we are told, not for the first time: over there, in the mountains. “It’s a tragedy I will never forget,” confides one of the sons, twentyish, about the latest murder. The mother removes her scarf, unties her hair, then her braids, under the yellow light bulb. “Hallelujahs” arise from the adjoining church; the old man laughs. He will give me, a few days later, roots to ease a momentary fever: “It’s better than chemistry.”

![]()

We’re at the home of B., one of the compas in charge of overseeing the Brigade. He is never without his walkie-talkie and tells us of his growing interest, poco a poco, little by little, in what the left has to offer regarding ideas and theoretical frameworks. The concrete, ordinary struggle was, first and foremost, what had pushed him to join. “If Marcos is supporting the presidential candidate, she must be good.” B. reproves those evangelicals in the community who don’t get involved, “not wanting any problems,” then castigates the “opportunists” who agree to government money despite criticizing it—all nonetheless need to live together, with “respect.” The community’s former mayor (“a bastard,” he blurts out, laughing) was “let go” some time ago: the locals have self-governed ever since.

Cafés steam and a cat passes by.

We snack on tamales, corn dough rolled into plantain leaves. His daughter, less than ten years old, is drawing and has every intention of pursuing her studies in the future. B. tells us a joke, interminable, that his wife gives corrections to or contradicts—depends, they’re both cutting off one another—about the king of Spain.

![]()

The sun opens a breach with a sluggish hand, haze, clouds worn pink by the red he carries. I stare, for a while, at a busy ant colony. Jules and I play chess together. We manufactured the board out of a lid we lifted from the bathroom’s garbage can; the pieces were carved from the cardboard flaps that act as our blinds. I lose every game.

A bag of onions on the table, a religious sermon on the radio, two or three chickens about the floor—we talk. “I would really like to be a Zapatista. But the majority of the community accepts government aid. It’s therefore difficult to imagine our complete autonomy, for the moment: we don’t have our own school, we aren’t ‘conscious’ enough,” confides V. in her red dress, gray bangs, and silver teeth. “I would also love to make do without pesticides, but we don’t know how. No one taught us.” A smile, akin to a pout of disappointment. “There is no justice,” she concludes.

Our departure is close—we’ll have, fortunately, no clashes to report.

![]()

“Toward the socialist revolution” announces one of the walls of San Cristóbal upon our return. This is where indígenas evicted from their lands are camping: hodgepodge of tents and banners, a portrait—another—of Zapata, assassinated a century ago. It’s here, precisely, that twenty thousand masked Zapatistas paraded in 2012, silent and disciplined, fists raised in front of flags bearing the colors of the EZLN and Mexico: “Did you hear that? That’s the sound of your world collapsing, and of ours arising.” Jules intends to stay for some time yet; I reach Mexico City by bus, thinking of Trotsky, felled here one August day, skull shattered. Yes, when is the collapse? ![]()

[1] The name of an infamous set of laws that formalized the repression of colonial subjects throughout the French Empire from 1881 to 1947.

Joseph Andras is the pen name of a French author, most notably of the novels De nos frères blessés, Kanaky, and Au loin le ciel du sud. Born in 1984, he lives in Normandy when not on extended stays abroad.

Simon Leser is a PhD candidate at NYU. He translated Joseph Andras’s first novel, Tomorrow They Won’t Dare to Murder Us, published by Verso in 2021.