We went bowling after work for team building. I found a severed finger, calm and blue, on the floor near lane number five. It still wore a wedding band. Joanna suggested we phone for help. Ann told Joanna to stop using phone as a verb, nobody here was British. George suggested it was a prop finger, perhaps left over from Halloween. Joanna disagreed. Mary was singing the latest earworm song of the summer and Joanna told her to shut her face already because this was serious. Ann loved George who was married to Mary who was in love with Joanna. I was trying to find love myself and hoped the severed finger was pointing the way.

It pointed, suggestively, in the direction of Joanna.

We worked in a building that was designed to look like ships sailing through rough seas. A metaphor for commerce, my welcome email told me. The man who built it, Bob Oscar, owned the apps for most of what the world consumes. Food, drugs, entertainment, relationships. I worked on the floor that sold the app that finds you love. Many long years of planning were put into how to make money on the app that finds you love. The team brainstormed, pounded their heads on the meeting table, ordered catered lunches, played beer pong, decided they needed another round of funding, realized maybe it was sex they wanted to sell instead of love, but were told that the app that finds you sex was on a different floor therefore they’d better stick to love. Love it was, then. But morale was low. They bought new hoodies for the team. A robot coffee maker for the breakroom. Hoverboards for the mail guy. There was almost too much good living to care about selling love. Everyone was too wasted on lunch hour cocktails to answer emails. They wanted to change the way the world finds love, but it was getting hard to find anyone left who deserved it.

![]()

One of my jobs was to write the office newsletter.

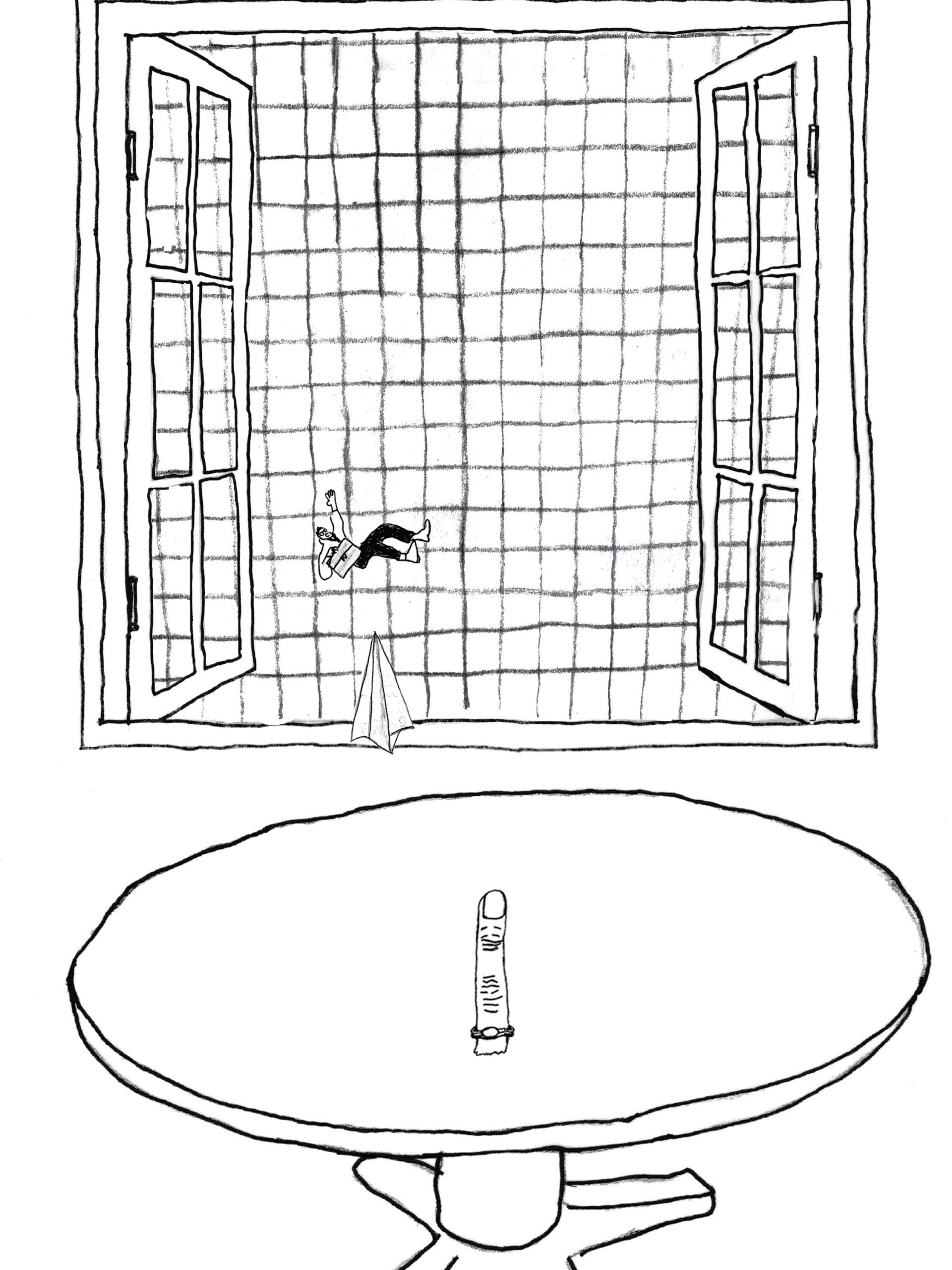

I wrote about the chaos and mystery of life. From my desk I could see the window washers on the new skyscrapers. They were like angels with broken wings when they fell.

But I digress.

Joanna had ancient eyes that made you want to write a song about her. I wanted to realize her, in an animal way, on account of the severed finger suggesting it.

Everyone else was boring, or worse.

George, my deskmate, had a passive-aggressive streak and wore only orthopedic shoes. He danced outside twice a day as instructed by his doctors for stress. Mary and Ann liked to order out for sushi and they’d make me hold their soy sauce in a little bowl for dipping like a priest.

I don’t really like holding people’s soy sauce, I said.

Oh come on, they said. This job is actually terrible. Getting our soy sauce held is the only thing we have that gives us meaning anymore. Take that away, we’ll jump off the roof.

Okay, okay, I said and the years rolled by.

![]()

I looked out at the skyscrapers often and thought about those workers up there balancing their lives away and I almost understood why they jumped. Or was it that they simply stopped trying not to fall?

I didn’t have time to wait for answers.

I tried to talk to Joanna with my eyes. I tried to use the app to tell her that I loved her but it only showed me women who were seeking love, not women who didn’t know love was staring them straight in the face.

Anyway, I had a newsletter to run.

There had been stories online about how wacko everything in America was and I got pretty worked up about all that. Acid in drinking water and pedophile bankers and terror, all kinds of terror, filling the streets. It was hard to know the difference between mercy and pain. It was like everything was beautiful and bad.

George was always saying maybe the universe was an alien hologram. Or that our world is someone else’s dream. I said that was nonsense. Instead, I was convinced we were all made from the same cosmic dust. I was the same thing as a house cat, a nuclear submarine, and Joanna.

But Joanna felt so far away.

I wrote all this up and put it in the newsletter. Told my fellow workers of the struggle, the corporate ennui. I cast our daily slog as the long and meaningless fuckery of time.

Outside, the helicopters circled the skyscrapers. They made shadows the size of pterodactyls. Everyone was going bowling again after work for team building. Joanna raised her eyes to me once that day. She had dark Spanish eyes, red French lips, and a big dumb American mind.

![]()

Outside, rain came down like a soft curtain.

I’d always been a daydreamer. In school my teacher would be going on and on about parallelograms and I was crossing the Alps on a hovercraft. Back then love was wild and easy. In my dreams I went everywhere. Played dominoes on the moon. Drank Shirley Temples with Marie Antoinette.

I put all that in the newsletter too.

But most days the world seemed too grave and annoying to get back to doing any actual work. I thought of shooting someone, or myself, but changed my mind so many times I gave up. At home I kept the blinds low, avoiding the light. Woke up still dreaming of Joanna and her international body.

Sometimes the words of the newsletter rearranged themselves and came back to me as poetry. They made a bow and arrow and I shot it at Joanna’s heart.

![]()

Then something not so good happened.

Everyone in the office actually started reading my newsletter. Mary lost it on George. She said all love between men and women was assault. George told Mary he thought that was a radical position for her to take, seeing as she was the one. The one what, Mary asked. George said nothing. He watched Ann. She was in the corner harming (or pleasuring) herself, barely concealing it. The interns were slowly deleting the hard drives.

Did love mean anything anymore or was it all a wildfire, destroying everything as it grew?

I tried to talk to Joanna with my eyes again.

Nothing seemed to work and so I dreamed a little more. Somewhere out there, in the forests and jungles, millions of animals were brutally murdering each other without love, craving no meaning.

I watched the river reflected in the windows of the building next door. The water seemed trapped in the glass.

![]()

Soon after that the crash came. Everyone lost everything. The bosses began jumping from the executive suite. I sat in the breakroom, trying to explain to the robot how I liked my espresso. I opened the window. I wrote out the last newsletter by hand on a legal pad and folded the pages into paper airplanes and aimed them at the falling billionaires.

I took the severed finger from my pocket. The wedding ring reflected in the dull fluorescent light.

I spun it once and then again. It pointed, suggestively, to the open window. I walked over and felt the cold air. The sun was going down. Joanna took my hand. She closed her eyes as if in prayer. I turned to her.

If things were different, I asked, could you ever see yourself with a poor boy like me?

She didn’t speak but I knew what she wanted. She wanted to make love on black sand beaches beside blue crashing waves. She wanted to live outside the law. She wanted a best friend. She wanted to eat guiltlessly all the meals denied her through the years by her own desire to stay attractive in the cruel world. She wanted a dog. She wanted a sheepdog. She wanted a sheep too. A flock of them and strong boots and a countryside to roam around in and a stout umbrella and a warm wool coat against the storms. She wanted better vision. She wanted a song to sing. She wanted to harmonize with the vibrations of the earth. She wanted to be free from suffering. She wanted to dance on the razor’s edge of madness and be home in time for dinner.

She too could see yearnings in my eyes.

She could see I wanted a new way. I wanted to hold her hand. Something fundamental was moving between us, lover and beloved. A weird gravity urged us toward a most drastic conclusion. Of course it didn’t matter what we desired. We were subject to the constant tug of insignificance.

I’m not sure I could love you, Joanna said. To be honest, I’m not in the mood.

That’s the trouble, I said. No one’s in the mood.

There was another long pause like so many before it. Was it awkward or dramatic, I couldn’t tell.

You know nothing about me, she said.

I wanted to tell her that I knew everything about her. I knew her deepest fears. I knew the names of her invisible friends. I knew the way she drank her martinis. I knew her favorite day of the week. But then, quite slowly, perhaps it was the length of the pause, the weight of it, that caused me to understand that in fact I knew nothing about Joanna at all. I didn’t even know her last name. I didn’t know where she was from. If I’m honest, I didn’t want to know any of those things. I just wanted her to want me.

I understand, I said.

![]()

I used to daydream when I was a kid about what I’d do with three wishes. After I wished for more wishes and I’d gotten everything I ever wanted, I started to build in my mind a new society. One without gods and bosses. There would be no more need for money and no more need for love. The only law would be irrelevance. Everyone had to strive in my new world to become less and less relevant. All things trending toward laziness and indecent fun. If someone tried to play King of the Mountain, I’d destroy the mountain. But always there would be some spoiler in my daydream. Some pedant who would point out that this new lazy community was all well and good but how are we going to eat? Who was going to take care of the babies? And while we’re on the topic, while everyone’s out having big fun, who the hell was going to make the babies? I never had an answer to these questions. And soon the daydream would fade and I would return to the world of glass and water.

This is what I was thinking about when Bob Oscar himself walked in. He was shirtless and drunk. For a moment I thought he was holding a weapon but it turned out to be a small radio that was tuned to the news. It squawked out sad headlines.

A life’s work, Bob said. All gone in an evening.

He was edging toward the open window.

Are you okay, asked Joanna.

What’s your name, Bob asked.

Joanna, she said.

How long have you worked here, he asked.

Almost two years, she said.

Bob looked down at his feet.

I wish we could’ve gotten to know each other, he said.

I almost pushed him, but he did the job for me.

Then George and Mary and Ann made their way into the break room. They’d been chasing Bob Oscar, it seemed. The coffee robot was out of control, spitting hot water into the air like venom.

Where is he, Mary asked.

I motioned toward the open window.

George and Ann were holding hands.

We all poked our heads out into the dangerous night. I was envious of all who could jump so freely. I could feel the black wind in my hair. We were finally a team and maybe more. Maybe a family. Soon a decision would need to be made, but not yet. There was nowhere else I wanted to be. ![]()

Michael Bible is the author of the novels The Ancient Hours, Empire of Light, Sophia, and Cowboy Maloney’s Electric City. His work has appeared in the Oxford American, Paris Review Daily, The Guardian, Vice, The Baffler, and New York Tyrant. Originally from North Carolina, he lives in New York City.

Illustration: Nick Stout